Introduction

The middle third of the face fractures are more vulnerable to impact or strength of the attack due to the facial skull anatomical components and to the absorption of external forces.1,2

These fractures have a high incidence rate and variable etiological factors such as motorcycle and automobile accidents, physical aggression and falls. Men aged 20 to 30 are the most frequently affected.1,3,4,5)

The role of the mechanism of the injury in the development of fractures as well as the comprehension of the distribution of forces over the craniofacial skeleton have been in focus in current research.1,2,5 Therefore, this helps with diagnosis and treatment through the clinical and radiological aspects.6,7,8)

The classification proposed by René Le Fort is the most used among the several different kinds of classifications of maxillary fractures.3,7,8,9) He classified the middle third face traumas into three patterns of fractures, through direct observation of the weak lines/points in the craniofacial skeleton: Le Fort I, Le Fort II and Le Fort III.6,7,8)

Le Fort I fracture, or horizontal fracture, is defined by a line that commences at the pyriform margin, passes above the dental apexes and canine fossae, involves a portion of the zygomatic buttress and then ends in the inferior portion of the pterygoid process.4,7 It is usually caused by horizontal excessive force applied over the three sustaining maxillary pillars.5,8,10 Different from the Le Fort I fractures, forces applied to a higher level direction result in Le Fort II and Le Fort III fractures.10)

However, patterns of facial traumas may vary, so that in some cases it may not be possible to perfectly fit them in the classification originally developed by René Le Fort.6,11,12) Atypical fractures, with different characteristics from the previously mentioned patterns, can be caused due to impact force, mechanism of the trauma, as well as the facial biomechanics.6)

The treatment of Le Fort I fractures aims to restore masticatory function and aesthetic appearance. Therapeutic approaches are commonly performed with wide exposition of the fracture lines, anatomical reposition and stable fixation of the segments in all planes using titanium plates and screws.1,8,13 The key criterion to reduce these fractures is to evaluate the direction from which the trauma was caused, as well as to fix the plates in parallel directions to the chewing forces.14

The aim of this paper is to describe the clinical management performed on a victim of the middle third of the face atypical type Le Fort I fracture in addition to highlight the main characteristics and analyze the classifications for this pattern of fracture.

Case presentation

A thirty-three year old man was seen at the Surgery and Maxillofacial Traumatology Service of the Senator Humberto Lucena Emergency and Trauma Hospital - Joao Pessoa (PB), Brazil, victim of physical aggression.

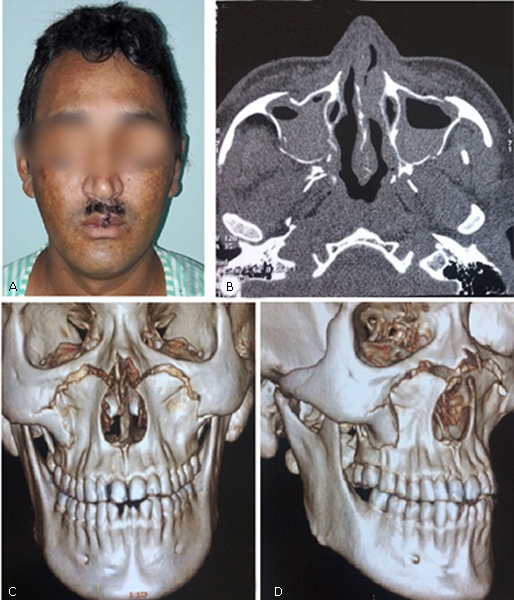

The patient was conscious and lucid, with clinical characteristics of sinking of the middle third of his face, edema and bilateral periorbital ecchymosis (Fig. 1, A), visual acuity and ocular motricity preserved in both eyes, a cut-contusion wound on the upper lip and maxillary mobility when handling, limited opening of the mouth compatible with the condition, and discrete occlusal dystopia.

The imaging exam showed a line of fracture going through the right maxillo-zygomatic suture, extending to the right infraorbital margin, perpendicular to the right naso-maxillary suture, inter-nasal suture and left naso-maxillary suture, and proceeding towards the left infraorbital margin and ending at the left maxilla-zygomatic suture, compatible with a high Le Fort I fracture (Fig. 1, B - tomography; Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1- A: Clinical characteristics of sinking of the middle third of his face, edema and bilateral periorbital ecchymosis. B: The characteristics of imaging exam tomography. C and D: The imaging exam showed a line of fracture compatible with a high Le Fort I fracture.

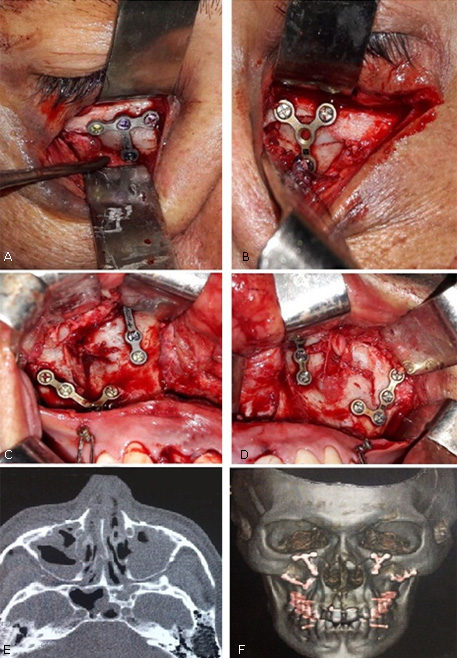

After stabilization of the clinical picture, the patient underwent general anesthesia. Osteosynthesis of the fracture with plates and screws made from titanium 2.0 mm system over the zygomatic buttress and over the infra-orbitary margins were performed through bilateral vestibular and bilateral subciliary approaches (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2- A: Subciliary approaches right and osteosynthesis of the fracture. B: Subciliary approaches left and osteosynthesis of the fracture. C: Vestibular approaches right and osteosynthesis of the fracture. D: Vestibular approaches left and osteosynthesis of the fracture. E and F: The imaging exam showed a osteosynthesis of the fracture with plates and screws made from titanium.

The patient progressed satisfactorily with good middle third of face symmetry, discrete scars on lower eyelids, expected closure of intraoral wound, satisfactory mouth opening, maintained occlusion and absence of paresthesia of the infra-orbitary nerves. The patient is in the seventh month of the postoperative period without aesthetic and functional complaints (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The fact that the middle third of the face is our main focus of attention is because alterations involving or acquired in the region are very noticeable, so there is a clear concern in literature about fractures and sequels in this region.3)

Bezerra et al.2 reported that 88.2% of the studies analyzed indicated a higher incidence of the middle third of the face lesions happened in males, corroborating with this case report, as well as the study by Regmi et al.,13 which described a ratio of males to females of 4:1. Ravikumar et al.12 justify that men are more susceptible to maxillofacial traumas since they expose themselves more to risk factors such as automobile accidents, physical aggressions, sport injuries and falls associated with the consumption of alcohol.

According to the age distribution pattern, Oliveira-Campos et al.11 showed a higher incidence of middle third of the face fractures in 21-30 year old patients (38%), followed by 31-40 year old patients (26%), consistent with this case report, as well as the research by Ravikumar et al.12 in which 21-30 year old patients had a higher incidence, followed by 31-40 year old patients (21.9%).

The etiology of middle third of the face Le Fort fractures is variable. Oliveira-Campos et al.11 reported that the main cause of the Le Fort I fractures (n= 22) was motorcycle accidents (n= 8), followed by physical aggressions (n= 6). However, Regmi et al.13 reported that motor vehicles had a higher incidence (62.5%), followed by falls from their own height (22.5%).

The René Le Fort classification is consolidated in literature as the most used and appropriate to the middle third of the face fractures. However, studies are being conducted encouraged by alterations in the facial trauma patterns.7,11,12

One of the possible justifications for the location of atypical fracture lines was described by Roumeliotis et al.14 in the study that evaluates the craniofacial traumas comparing the fracture pattern related to the strength of the impact. The authors stated that most of the Le Fort I fractures result from low-energy traumas, according to this case report and to the case related by Sukegawa et al.15 High-velocity traumas may also result in Le Fort I fractures, but at higher points than the conventional ones.6) Besides the impact force, the trauma mechanism and the facial biomechanics can also be considered as possible explanations of atypical fractures with characteristics that do not fit perfectly into the classification system.5,6,7

Despite Le Fort I fractures having minimal clinical signs, flattening of the face or asymmetries, cracklings, maxillary hypermobility, malocclusion problems (especially open frontal bite) can be visualized.3,12 Such alterations can be considered potentially disfiguring,4,8,12 and these characteristics were present in the patient in this case report.

A Le Fort fracture can be diagnosed clinically and by imaging examinations.3 Cone-Beam computed tomography (CBCT) has become the imaging technique of choice to evaluate cranio-maxillo-facial lesions, due to the fact that it allows the visualization of the multiplicity of fragments and degrees of rotation, displacements, and also requires lower doses of radiation than convenctional computed tomography.2,10) CBCT and 3D reconstruction of the facial skeleton are extremely important tools to analyze and understand the spatial configuration of the fracture lines, and to update classifications and therapeutic approaches.

The treatment of Le Fort fractures aims to realign fracture lines for complete functionality as well as good aesthetic appearance.1,8,13 In general, the treatment should be performed with stable fixation of the segments in all planes.3 There is a great variety of incisions in the approaches that require fixation in the middle third of the face, such as: subciliary, subtarsal, upper vestibular and coronal incision.14 In this case report we started with the approach of bilateral vestibular access, which did not allow us a complete access to the fractures. So we chose to associate the bilateral subciliary access, guaranteeing a complete exposure and a minimal aesthetic repercussion to the patient, since it is performed on the line of facial expression in the lower eyelid.

In cases in which it is not possible to perform this fixation, the possibility of facial elongation, facial retrusion and displacement of the middle third of the face are considered.8 However, Oliveira-Campos et al.11 observed that conservative treatments (n= 6) were preferable for Le Fort I fractures, followed by open reduction (n= 4) and finally, the option of not performing any treatment (n= 1).

Final considerations

Le Fort I cases that flee the pattern are not so frequent and are justified by the different etiological agents and, above all, by the force of the impact. It is well known that the occurrence of high velocity traumas can result in Le Fort I fractures, but in points localized higher than the conventional ones.

In conclusion, therapeutic approach for atypical cases resembles and is based on classical Le Fort I treatments such as reduction and fixation with plates and screws, differing only in the individual adaptation of the accesses for this approach.