INTRODUCTION

Primary immune deficiencies (PIDs), also known as inborn errors of immunity (IEI), are a large heterogeneous group of genetically based disorders that affect the proper functioning of the immune system.

According to the most recent report by the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS), the identified IEI were classified in 10 groups: (a) immunodeficiencies that affect cell and humoral immunities; (b) immunodeficiencies combined with associated characteristics or syndromes; (c) predominantly antibody deficiencies; (d) immune dysregulation diseases; (e) quantitative or functional phagocyte defects; (f) innate immunity defects; (g) autoinflammatory diseases; (h) complement system deficiencies; (i) bone marrow failure or insufficiency, and (j) IEI phenocopies.1

PIDs can present from early childhood to adulthood and their clinical features are highly variable and include increased susceptibility to infections, lymphoid proliferation, association with allergies and autoimmune diseases, among others manifestations in variable combinations. Patients may be asymptomatic, present mild manifestations or to develop severe symptoms leading to their demise. Generally, the most severe, life-threatening conditions start in the first months of life, which has caused IEI to be mistakenly associated with exclusive childhood diseases.2

Also, PIDs have been historically considered as rare diseases, with low prevalence in general population. However, for the past years, molecular biology advances have led to the identification of new monogenic IEI and the description of novel phenotypes. The IUIS in their last classification update described over 400 PIDs, a number that is permanently increasing. In fact, the suspected worldwide incidence of these diseases ranges from 1/1 000 to 1/5000 births, depending on genetic background, environmental factors, social habits, and access to health services.1 In Cuba, 337 patients with inborn errors of immunity have been reported until 2019.3

The remarkable clinical variability, along with the high cost of the diagnosis of PIDs, contributes to turning their identification into a challenging task, particularly in developing countries, where statistics are likely underestimated and, consequently, a great number of patients remain untreated. Hence, clinical immunologists ought to address the report of PIDs as a mission of paramount importance.

A high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis; understanding the clinical features and particularities of PIDs presentation is key to raise awareness of these conditions in medical professionals and to ensure that patients with inborn errors of immunity receive proper sanitary care, therefore reducing morbidity and mortality rates, hospitalization and treatments costs and optimizing the use of resources. On the other hand, epidemiological studies of PIDs may help shed some light over the immune pathogenic mechanisms of these diseases, uncover public health blind spots to respond to patients necessities and to develop customized strategies to manage these patients nationwide.

Therefore, the objective of this research was to characterize clinically and demographically patients diagnosed with primary immunodeficiencies.

METHODS

A cross-sectional, descriptive, retrospective case series study was carried out with 39 patients of both sexes, who were treated at the Immuno-allergy service of the Outpatient Medical Centre attached to the "Carlos Manuel de Cespedes" Provincial Hospital of Bayamo, Granma province, diagnosed with primary immunodeficiency according to the last classification of the IUIS of 2020,1 in the period of January 2012 to December 2021.

The characterization of these patients was carried out through variables:

Age (of symptoms onset, diagnosis, and diagnosis delay: lapse of time between the appearance of the first symptoms and the immunology diagnosis).

Sex.

Family history.

Clinical manifestations.

Type of PID (classified according to the IUIS of 2020, from which the diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiency were taken.1

Data were collected from the medical records and from the questioning of parents and patients. The following methods were applied to obtain the data: observation, measurement and clinical method. The statistical methods used were the mean for ages, and for the rest of the variables absolute and relative frequencies. The information obtained was processed through IBM SPSS 25.0 statistic program.

To carry out this research, approval was received from the Ethics Committee of the Center, and the subsequent consent of those selected (or legal guardians, in the case of minors).

RESULTS

Out of the 39 PID cases, 23 (59%) were males and 16 females (41%), with a female/male ratio of 1:1.44. Besides, 28 patients were children under age of 18, representing a 71.79% of the sample.

The age of symptoms onset ranged from one month of life, in a patient with DiGeorge Syndrome, to 37 years in a case of IgG Deficiency, with a mean of 6.31 years. In children, the mean age of onset was 28 months.

The average age of diagnosis was 11.89 years; two cases of Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) were diagnosed at advanced age, between 54 and 62 years of age. Age of diagnosis in children was 3.88 years, in average.

The diagnosis delay was an average of 5.6 years. In children, this mean delay in diagnosis was 19.5 months.

According to their clinical manifestations, patients that presented with recurrent infections were diagnosed with a mean delay of 7 years, while those that also reported allergic symptoms had a diagnosis delay of 1.5 years. Patients with recurrent infections, allergies and autoimmune disorders had a diagnosis delay of 10.2 years, and those that presented with autoimmunity as a sole manifestation showed a delay in diagnosis of 14 years.

Patients with common variable immune deficiency had the highest mean age of diagnosis, onset and the longest diagnosis delay period (table 1).

Table 1 Age of diagnosis, onset and diagnosis delay of PIDs

| Primary Immune Deficiency | Mean age of symptoms onset (years/months) | Mean age of diagnosis (years) | Mean diagnosis delay (years/months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-linked agammaglobulinemia | 0.25/3 | 4 | 3.75/45 |

| Chronic granulomatous disease | 2/24 | 12 | 10/120 |

| Mucocutaneous candidiasis | 8/96 | 13 | 5/60 |

| IPEX like | 0.08/1 | 12 | 11.92/144 |

| Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) | 17/204 | 33.6 | 16.60/199 |

| Neutropenia | 0.77/9.5 | 1 | 0.28/3.5 |

| Thymic hypoplasia with clinic immune deficiency | 3.51/42 | 4.15 | 0.66/8 |

| DiGeorge Syndrome | 0.16/2 | 1 | 0.84/10 |

| Absolute deficit of IgA | 2.60/31 | 6.20 | 3.66/44 |

| Relative deficit of IgA | 3.55/42.5 | 5.66 | 2.16/26 |

| Deficit of IgG | 14/168 | 24.33 | 10.33/124 |

| Mixed antibody deficit | 2/24 | 2 | 0.08/1 |

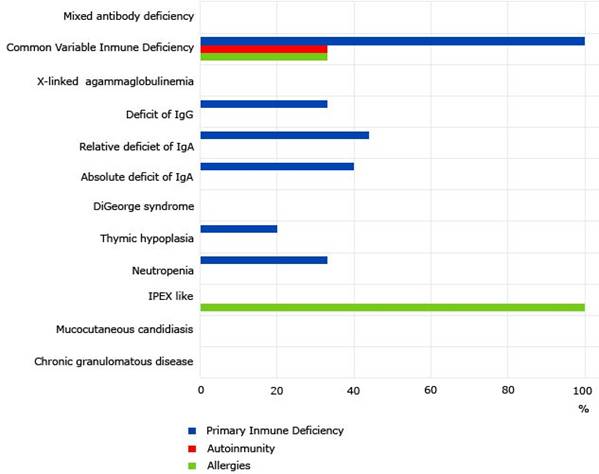

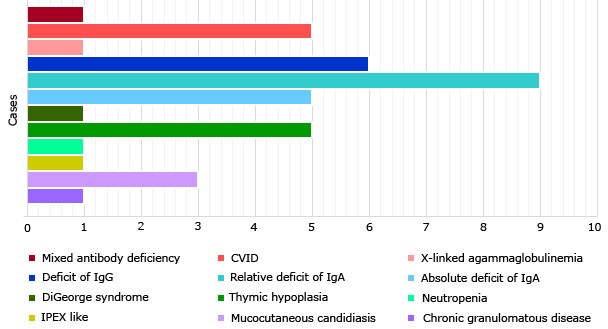

As showed in table 2, predominantly antibody deficiencies accounted for the larger number (69.23%) of all inborn errors of immunity, with a very similar distribution in both sexes (13 females vs. 14 male patients). There were not cases diagnosed with autoinflammatory disorders, complement system deficiencies or phenocopies of primary immune deficiencies.

The most frequently diagnosed immunodeficiency in the series was IgA deficiency, which globally accounted for 35.89% of all cases. Relative deficiency of IgA predominated, with 9 patients. IgG deficiency, absolute IgA deficiency CVID and thymic hypoplasia with clinical immunodeficiency occurred in similar order of frequency, with six, five and five cases, respectively (table 2).

Family history of primary immunodeficiencies was reported in 30.76% of patients (Fig. 1), who informed some type of familial antecedent of antibody deficiency, which corresponded to the exact immunodeficiency diagnosed in 58.33% of the cases. There was no consanguinity reported.

The most frequent clinical manifestations were recurrent infections, in 71.79% of cases, and allergic symptoms (61.53%), as it is shown in figure 2. The greatest variability in clinical expression occurred in predominantly antibody deficiencies; 3 asymptomatic patients were reported, who were studied due to family history of PID. Only 1 patient, with a diagnosis of CVID presented a neoplasm; 4 patients with simple humoral deficits had an atopic condition as a soul clinical manifestation and 2 cases presented only with autoimmune diseases.

A patient with chronic granulomatous disease died, for a mortality of 2.56%.

DISCUSSION

The demographic characterization of the sample shows a clear predominance of inborn errors of immunity in males. The United Kingdom PID (UKPID) registry reported a greater number of women with PIDs than men, 2.399 and 2.359, respectively;4 however, the rest of the consulted bibliography5,6,7 coincided with the results obtained by the authors.

In pediatric patients, the female/male ratio was 1: 2.29, while in adults, the disproportion between sexes was less marked, with a ratio of 1:1.75. This is associated with the fact that many early-onset primary immunodeficiencies are transmitted by X-linked patterns of inheritance; however, as age advances, this factor loses relevance and other variables come into play that balance the statistics, particularly associated to the appearance of immune dysregulation disorders.8

While, the 71.79% of the patients studied (28) were of pediatric age, an expected result considering the early childhood onset and great severity of a large group of inborn errors of immunity, which threatens patients' life expectancy. The age of appearance of the first symptoms was variable, in correspondence with the behavior of the different types of immunodeficiency. According to a study published by Italian researchers, Common Variable Immunodeficiency is the only PID with a more frequent onset and diagnosis in adults (over 18 years of age) than in children5 which corresponds to the population studied.

In children, the average age of onset was 28 months. A Chinese study of IEI in 112 children reported a mean age of onset of 13 months;9 however, direct comparisons between investigations are impaired since the aforementioned study does not declare the age range of childhood.

The average age of diagnosis was 11.89 years, though this result was affected by very extreme ages of diagnosis in cases of CVID. Studies focused in children reported mean diagnosis ages ranging from 4.210 to 6.3 years,7 while in this series, age of diagnosis in children was 3.88 years, in average.

Diagnosis delay of inborn errors of immunity is an important factor associated with increased morbidity and mortality, since it delays the start of treatment and increases the risk of infectious and onco-proliferative complications. In the studied series, the lapse of time between the appearance of the first symptoms and the Immunology diagnosis was 5.6 years, in average. Common Variable Immune deficiency showed the greater delay, which corresponds to results obtained in the UK,4 though the UKPID reported a 4 years delay against the 16.6 years showed by our study. This difference might be in correspondence with the degree of socioeconomic development of both nations and the access to diagnostic tools.

It was interesting to notice that the cases that presented with frequent infections and/or allergies alone were diagnosed earlier compared to those that presented with autoimmunity associated or not with other manifestations. An investigation conducted by Garcia-Torres et al.7 also pointed to a relation between quicker diagnosis and severe recurrent infections, as well as autoimmunity manifestations and diagnostic delay.

Most of the studies consulted report a lesser diagnosis delay in patients presenting with infections.4,9,10 This might be explained by the fact that, in contrast with patients with allergies or recurrent infections, who are often assisted by immunologists, patients with autoimmune manifestations are generally evaluated by a series of specialists before they are referred to an immunologist.

According to the IUIS classification,1 the group of inborn errors of immunity with the highest reporting were predominantly antibody deficiencies, which coincides with the global records of IDPS.6 No cases of autoinflammatory disorders, complement deficiencies or phenocopies of primary immunodeficiencies were diagnosed.

The most frequent immunodeficiency in the series was IgA deficiency, which globally represented 38.46% of the total cases. IgA deficiency is also the most diagnosed PID in Cuba (32% of all cases),3 as in the American continent, ranking second in order of frequency in Asia and Europe.6 However, in Pakistan, chronic granulomatous disease predominates, a phenomenon associated with the country's high rate of inbreeding and consanguinity (95% in the study sample).10

Though consanguinity is rare in Cuba, a study published by Lugo et al.11 reports that approximately 1.1 billion people currently live in countries where consanguineous marriages are customary: in Middle Eastern, North Africa (MENA) and West Asia countries, a geographical area that runs from Pakistan and Afghanistan in the east to Morocco in the west, and including South India.

It is directly associated to an increased rate of autosomal recessive IEI in siblings with unaffected parents. Even when there were no reports of consanguinity in the series, the familial incidence was high compared to the German registry of PIDs (30.76% vs 21%, respectively) which reported an 8% of patients with related parents.12 The German study showed that familial cases are more common in CVID and other humoral deficits, CGD and SCID, while in the present investigation a family history of IEI was more relevant in IgA and other humoral deficits. This difference might be associated to the low representation of CGD and SCID in our sample, as well as the prevalence of predominantly antibodies IEI.

Infections were the most common manifestations in our series. Although most national registries show similar results,5,8,10,12 non-infectious symptoms are been reported increasingly in the course of IEI. The UKPID registry recounted nearly 25% of cases with symptoms other than recurrent infections,4 a lesser figure compared to our results. However, the studies consulted showed relevant disparities in the methodology used to classify non-infectious manifestations, hence, comparing and extrapolating results is not feasible.

The mortality in the series was low. Lougaris et al.7) compared the mortality rates in patients with IEI according to the European registries; our series shows similar figures to populations in Germany and Switzerland.5 A Mexican study showed a slightly higher percent (3.3%), while in Pakistan the mortality raised to 25%.10 There are several factors that influence the outcome of IEI, such as early diagnosis, environmental and genetic factors as well as the access to sanitary services. Immune deficient patients with a history of parental consanguinity have been found to present with more severe PID phenotypes, as documented by the significant numbers of complications, atypical, severe and unusual infections, poor performance status, and a higher mortality rate.13 In Cuba, a third-world country, even when there are objective difficulties to make an accurate genetic diagnosis, the public health system ensures the access of general population to medical services and the affordability of treatments.

Primary immunodeficiencies were more frequent in childhood, with the same behavior in both sexes. Humoral immunodeficiencies were the most prevalent. Infections, allergies and family history of primary immunodeficiency were important finding.