SOCIAL INNOVATION AND ITS DIFFERENT THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

In recent years, studies related to social innovation (SI) have spread around the world. Under this term the diffusion of social ventures and experiments in social organization which involve actors from government, business and civil society are often simultaneously labeled as social innovation. (Fontan, Longtin & René, 2013; Hassan, 2013; Edwards-Schachter &Tam, 2013; Edwards-Schachter & Wallace, 2015).

SI has been gaining centrality and relevance in the discourses and practices promoted by social and political agents (Hernández & Rich, 2020), even though it is recognized as a multidimensional and highly complex phenomenon (Nicholls, Simon & Gabriel, 2016). This growing interest has oriented the discussion and debate towards various areas among which can be cited: economics and social entrepreneurship (Mulgan et al., 2007; Rodríguez & Alvarado, 2008; Analuisa, Toapanta & Borja, 2019); governance, including public policy and local participation; civil society and empowerment; and collective action (Esguevillas, 2013; Morales, 2014; Eizaguirre, 2016); corporate social responsibility (Chaves et al., 2013), social challenges and changes, and urban development strategies (Moulaert & Nussbaumer, 2005; Hubert, 2010; Rodríguez & Medina, 2020).

The first line of studies focuses on the main academic debates, which increasingly form an intricate network of projects, studies, conferences, and publications. In practice, the SI phenomenon is conceptualized in a flexible and open way. For some it is an ambiguous concept (Lévesque et al., 2003), covering both theoretical contributions, originating in a diversity of approaches and disciplines, and a great heterogeneity of practices originating in everyday social life (Hernández & Rich, 2020). This situation poses a series of difficulties (not to say impossibilities) in establishing the theoretical and methodological foundations necessary to carry out rigorous research.

Valle (2017) advances in the identification of three dominant positions in the process of conceptualizing SI. The first focuses on non-technical innovations in the organizational context (Heap, Pot & Vaas, 2008), the second focuses on the connection between SI and technological innovation (Howaldt et al., 2010), and the third responds to the study of SI as a new social practice (TEPSIE, 2012; Morales, 2014).

In general, SI is understood as a way to create new and more effective responses to the challenges facing the world today. It is a field with no limits, it can be developed in all sectors, whether public or private, for-profit or non-profit, and where the most effective initiatives take place when there is collaboration among different areas, stakeholders, and beneficiaries. It is usually defined as «a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient [...] than existing solutions and for which the value created corresponds primarily to society as individuals rather than private individuals» (Phills, Deiglmeier & Miller, 2008, p. 39).

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), while relating the SI to the identification and delivery of services that improve the quality of life of individuals and communities, has focused its attention on the need to advance in its understanding, particularly due to the recognition of the multiple nature of these processes and the absence of a consolidated definition and therefore the desirability of one (OECD, 2011; OECD, 2015). In such a way that part of the academic literature on the subject (Phillips, Alexander & Lee, 2019), recovers the proposal elaborated by defining it as « [...] a group of strategies, concepts, ideas and organizational patterns with a view to expanding and strengthening the role of civil society in response to the diversity of social needs (education, culture, health)» (OECD, 2011, p. 13). Social needs and problems that have been inadequately and unsuccessfully addressed by both governments and the market.

In an intermediate position, between more theoretical analyses and pragmatic positions oriented to the transformation of the social space, is located the second line of study identified by the authors oriented to the measurement of the SI, i.e. « [...] the construction of indicators that allow consolidating the concept and the possibility of identifying this type of initiatives, in addition to being able to quantify the capacities to innovate in social terms» (Santamaría and Madariaga, 2019, p. 114).

Associated with this line the research that leads to the present text is developed, whose objective is to determine the predictors for SI in social economy initiatives (SEI) in the city of Ibarra, capital of the Province of Imbabura in Ecuador. The predictors that were developed are oriented to the variables: climate of innovation, economic value, social value for clients and social value for the community in the SEI of this territory. According to Buckland & Murillo (2013), it is necessary to understand and address the urgencies in the most immediate context, and for this «[...] proven, tested and working initiatives are needed, which provide some kind of social impact - local or global - that is measurable [...]» (p. 6).

The text is structured as follows. The analytical framework related to the SI is identified, and its link with the SEI proposals is analyzed. Predictors for the SI in SEIs linked to the city of Ibarra are determined for the variables of climate for innovation, economic value, social value for the client and social value for the community. To achieve this objective, multiple linear regression is used to determine whether the explained variable (SI in SEIs) is correlated with the regressor variables (environment for innovation, economic value, social value for the client and social value for the community).

SOCIAL INNOVATION AND SOCIAL ECONOMY. CONVERGENCES

In the context of the crisis and the questioning of the global development paradigm, a third institutional sector of the economies, located between the State and the private for-profit sector, has gained in value. Called social economy (SE), it integrates private economic initiatives, controlled by the community and at the same time benefiting the social groups that compose them. Although it is not considered a new sector, since cooperatives and other associations have their origins in the 19th century, its potential has become more evident today.

Just like with IS, the literature on ES is abundant in terms of definitions and elements that comprise it. However, it is possible to find authors who manage to identify common features. Inglada, Pérez & Sastre (2020), point out, for example, «the preeminence of the person over capital, the preponderance of the social object over particular benefits, the concurrence between particular and common interests, the respect for the principles of solidarity and responsibility, and the promotion of sustainable development» (p. 3).

Among the studies linking the SI and SEIs are (Esguevillas, 2013; Morales, 2014; Eizaguirre, 2016; Valle, 2017; Santamaría and Madariaga, 2019; Analuisa, Toapanta & Borja, 2019; Hernández & Rich, 2020). In general terms, their results show that:

The social objectives of economic activity are very present in SEIs.

SEI practices are very active in innovation.

Social welfare.

This sector fulfills macroeconomic and microeconomic corrective functions of different imbalances and substantive problems, of an economic and social nature (Stiglitz, 2009; López & Pérez, 2015; López, 2011; Monzón and Chaves, 2012).

Although some authors consider the studies that have analyzed the review of the synergies generated between both fields as scarce (Valle, 2017), if the previous analysis is taken as a starting point, it is possible to advance the thesis of convergence between SI and SE, by recognizing that both have a social mission, i.e., they provide social value to economic activity. This assumption is made concrete by considering that both can address social needs by providing innovative solutions capable of producing a change in social relations based on the inclusion of the most vulnerable groups and their participation in decision-making and access to sources of resources (Fernández, 2020).

Another element that contributes to the effort to make these perspectives work together is the fact that the SI offers novel ways of addressing the unmet needs of the collectivity, often through the emergence of new forms of organization (European Union, 2014). For their part SEIs, as an institutional form of the third sector, are characterized as inherently innovative in solving challenging social and economic problems (Monroe & Zook, 2018). This is aided by their ability to elicit all types of relationships with social actors of diverse backgrounds and characteristics, as well as their propensity to generate management models of a friendly and inclusive nature (Anheier et al. 2014).

The research is consistent with the second line of study identified by Santamaría and Madariaga (2019), which moves between theoretical proposals and pragmatic positions. The importance of determining the predictors lies precisely in that these allow measuring how SEIs in the city of Ibarra address social needs by providing novel solutions that account for their capacity to develop SI. It will be possible to consolidate a conceptual framework that interrelates the SI in SEIs and quantify how it is produced in practice.

The city of Ibarra, capital of the province of Imbabura, was identified as the context for the research. This city is recognized as a multicultural canton, with great ethnic diversity, so the issue of inclusion of the most vulnerable groups is a priority (López, Quelal & Rosillo, 2019).

The hypotheses proposed for the study are:

METHODOLOGY

For the development of this research, three types of organizations that are generated from SE were considered, that is, three forms of SEI (Barrera, 2007). They are solidary economic initiatives (IES) (Ruiz & Lemaître, 2016), new forms of organization (Presta, 2020), and social initiatives (Buckland & Murillo, 2014).

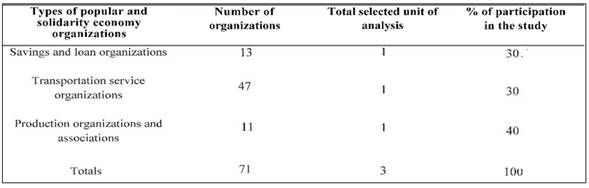

Under these criteria, 71 organizations are registered in the city of Ibarra by the Superintendence of Popular and Solidarity Economy, which are structured in three segments: savings and credit organizations, transportation services, and associations and production.

Three units of analysis were selected, one for each typology identified. The selection of these was based on «that, due to their sectoral characteristics, can develop substantive processes for the organization [...] such as the process of social innovation» (Valle, 2017, p. 187).

Other aspects taken into consideration were the capacities generated for the creation of new solutions, coverage of social needs and creation of new types of relationships (Table 1).

Table 1 Organizations of popular and solidarity economy in the territory.

Note: own elaboration based on the results of the research.

A purposive sampling was used. Rosillo et al. (2021), consider that this is used on the basis that «the researcher decides, according to the objectives, the elements that will make up the sample, considering those units that are supposedly typical of the population to be known» (p. 232). The sample consisted of 100 people related to the organizations in which the study was carried out.

The three organizations are registered as SEIs in the city of Ibarra. The segments surveyed were managers (6 %), employees (20 %) and customers (73 %).

In order to pilot the questionnaire used (Phillips, Alexander & Lee, 2019), (Ahuja, Yépez &

Pedroza, 2020), a panel of experts made up of academics and professionals was used (Bulut, Eren & Halac, 2013). The scale was constructed after a detailed analysis of definitions and propositions that appeared and were identified in the literature. It consisted of 20 items structured in five variables that measured social innovation, innovation climate, economic value, and social value for clients and for the community (Basantes-Andrade et al., 2023).

The design of the items took into account the different proposals collected in the literature, such as the correspondence between types of social economy organizations and manifestations of social innovation (Hernández & Rich, 2020); the creation of new solutions, coverage of social needs and creation of new types of relationships; social impact, economic sustainability, type of innovation, intersectoral collaboration, and the scarcity and replicability of the innovation (Buckland & Murillo, 2013); the proposal of Murray, Caulier & Mulgan (2010), presenting indicators of sustainability, social innovation, social impact and social orientation, networks, scale, replicability, governance and participation, patrimonial vectors. In addition, social impact, economic sustainability, type of innovation, cross-sector collaboration, scalability and replicability (Buckland & Murillo, 2014). The Experiences in Social Innovation in Latin America and the Caribbean project, an initiative derived from ECLAC with the support of the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (Rodríguez & Alvarado, 2008), considered the criteria for application, evaluation and awarding of projects.

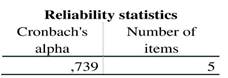

The responses to the questionnaire were marked by the subjects on a Likert-type scale (Ruíz et al., 2020). Cronbach's Alpha was assessed to obtain the reliability and construct validity of the instrument developed.

Afterwards, multiple linear regression was performed (Cruz, Urrutia & Salazar, 2011; Phillips, Alexander & Lee, 2019), specifically stepwise multiple regression analysis, whose purpose is to identify the predictive level for social innovation in social economy initiatives of the variables innovation climate, economic value, social value for customers, and social value for the community.

Dependent Variable

Social Innovation

Social innovation is a dynamic process driven by citizens to address social challenges. It prioritizes collective achievements and shared purpose, distinguishing it from private innovation. Social innovation varies in approach, scale, and direction based on the specific context. It generates value for society as a whole, not just individuals. These innovations enhance society's capacity to act and are driven by affected communities to meet their needs. They embody social values and aim to benefit society at large.

Independent Variables

Climate of Innovation

The approach to organizational climate must have a reference point to achieve its true purpose. A specific climate could enhance the social innovation developed by organizations. The innovative climate in social economy initiatives facilitates creativity and change, while empowering employees' independence in the search for new ideas. These aspects undoubtedly promote the development of innovations, regardless of their type.

Economic Value

One of the fundamental objectives of social economy initiatives is to create value for the community and society at large, while also contributing to gaining competitive advantages. It is acknowledged that these organizations enhance economic effectiveness by generating innovations and strengthening their visibility within the environment and competition. This, in turn, reaffirms the creation of value and its corresponding economic sustainability. Additionally, these initiatives have a social goal of finding solutions to social problems.

Social Value for Customers

Social value is a complex and integrative construct encompassing the economic and social benefits generated by an organization that improve the lives of individuals or society as a whole. It is one of the most important variables in this study, closely aligned with the mission of social economy initiatives. Such organizations have a significant impact on territorial and social cohesion, which are fundamental pillars for societal development. For social economy organizations, creating social value for customers and the community is a central aspect of their functioning. Valle (2017) recognizes that despite the limited research on this aspect, there is evidence suggesting a positive relationship between the performance of these organizations and the value created for society.

Social Value for the Community

It refers to the positive and tangible impact that an initiative, project, or organization has on the community in which it operates. It encompasses the social benefits generated through activities and practices that address specific issues and needs of the community, enhancing their well-being and quality of life. It involves the ability of an initiative to generate significant and sustainable changes in areas such as social inclusion, equality, community cohesion, local economic development, environmental preservation, cultural promotion, and other aspects relevant to the community's well-being.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The two-step data collection method was used: (1) pilot study to develop the scale and (2) final analysis (Bulut, Eren & Halac, 2013). «Coefficient alpha is assumed to be (α=.70) or more to consider the scale reliable» (García, Alguacil & Molina, 2020, p. 18). The KMO index value found was =0.698 and with a p < 0.000 in the Barlett's test of sphericity, so that the 20 items structured in the five variables possessed a correct fit. In the analysis, items decreasing the alpha value were eliminated and elimination was stopped when the desired value was reached. The obtained value was (α=.739), which is quite satisfactory considering the established criteria (Table 2).

We proceeded to assess whether a data sample follows a specific distribution. For this purpose, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied, considering a sample size of (n=100). The results indicated that there is no normal distribution of the data under the assumption of (p≤0.05) for all variables (Table 3).

Table 3 Normality tests: Kolmogorov-Smirnov.

Note: own elaboration based on the results of the research.

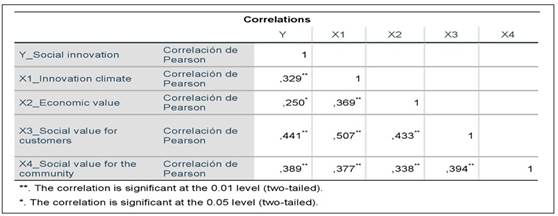

A Pearson correlation was performed between the scales used. As shown in Table 4, all variables show a statistically significant relationship, with the variable 'social value for customers' exhibiting a strong correlation with social innovation (R=.441). On the other hand, 'economic value' and social innovation show a weak association (R=.250). The remaining variables show moderate relationships.

Table 4 Pearson correlation matrix between variables.

Note: own elaboration based on the results of the research.

The present study aimed to investigate the predictor variables of social innovation in SEIs in the city of Ibarra. In this regard, the identified hypotheses and established objective contributed to clarifying this issue. This result is consistent with hypothesis H1: The combined multiple linear regression model of the construct of variables positively correlates with social innovation in SEIs. It is accepted. The multiple correlation coefficient is positive, showing significance.

The result is consistent with the study of Valle (2017), which interrelates social entrepreneurship, leadership, social capital, organizational climate, social innovation and both financial and social results. As an organizing element within the proposal, the organizational climate that facilitates a favorable environment for communication and participation is highlighted, in addition to allowing the transmission of the vision, objectives and necessary values of the project.

Another element of integration that highlights the result achieved corresponds to the ecosystem approach of the SI. It suggests that the SI usually arises in an ecosystem composed of individuals and organizations of various sectors and types. Social capital can be understood as the relationships and information flows, as well as the resources necessary for this ecosystem to be alive and operating (Buckland & Murillo, 2013, p. 37). This interaction includes the creation of social value for both the customer and the community, which finds its description and support in the literature (TEPSIE, 2012). In addition, organizations are oriented to conceive objectives of a social nature (Mair & Martí, 2006).

The other variable that is related has to do with the economic performance of the SEI and the adoption of innovative actions, which will improve its results (Castro, Galán & Bravo,

2014). The role of the social orientation of organizations is reinforced. Rüede & Lurtz (2012), point out that the social in SI, «is combined with change in social interactions, in favor of disadvantaged and socially excluded members of society» (López, 2014, p. 130).

Studies conducted by Arcos, Suárez & Zambrano (2015), show that SI processes integrate human, financial, administrative, and technological resources. In addition, they imply the need to develop a combination of capacities and skills that allow initiatives or projects to be sustainable over time and generate favorable social transformations.

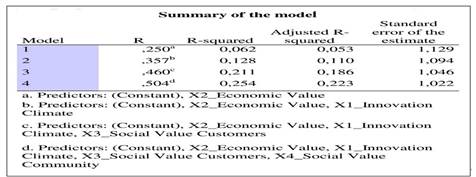

Once the reliability of the scales used has been analyzed and their correlation shown, we proceed to perform the step-by-step multiple linear regression analysis, using the forward method, to differentiate the contribution of each variable to the problem-solving test score. As can be seen in Table 5, the multiple correlation coefficient was positive (R=.504) and explains 22 percent of the adjusted variance (adjusted R^2).

In the first step of the analysis, economic value was included as a predictor in the equation (R=0.250), explaining 0.5 percent of the adjusted variance (adjusted R^2=0.053) (p≤0.05) and serving as the baseline. In the second step, innovation climate was included as a predictor in the equation, followed by social value for the community and social value for customers. Each variable added to the model increased the predictive value of the predictor variables. Social value for customers was recognized as the strongest predictor of social innovation in higher education institutions, explaining up to 25 percent (adjusted R^2=0.223) (p≤0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5 Correlation matrix of predictor variables and dependent variables.

Note: own elaboration based on the results of the research.

Another approach to innovations recognizes that, at the organizational level, the success and effectiveness of changes depends on the overall effort made by the organization. Organizations that present a work environment characterized by initiative and psychological safety show a higher probability that their innovations will be implemented effectively (Baer & Frese, 2003). At the individual level, in addition to the relationship between innovation climate and work attitudes such as commitment, in recent decades its relationship with different levels of behavior, such as innovative and collaborative behaviors, has also been analyzed.

The results achieved by the organization, in general, are appreciated as an indicator of the viability of the initiatives developed. In the study conducted, this aspect has become more important for SEIs. These organizations have developed the characteristics of other institutions participating in the market. This may be caused by approaches to social enterprises (organizations that have a goal in common with social economy initiatives: to generate social value), and that try, to some extent, to justify or make it clear that this type of organization has a «significant level of economic risk. Those who found a social enterprise assume all or part of the risk inherent in the initiative. "Unlike most public institutions, the financial viability of social enterprises depends on the efforts of their members and workers to secure adequate resources» (Defourny & Nyssens, 2012, p. 16). In addition, it should be considered that of the SEIs used in the study universe, two present a profit motive, even though they are in this indicated economic segment.

The literature on social capital shows that organizations that take into account solidarity and existing social relations and seek to reinforce them through their intervention methods establish a more reliable relationship with their target population and have a more positive impact on the living conditions of their clients. This is achieved through products designed and adapted to the specific needs of the latter (women, youth, ethnic minorities, unemployed, etc.) in their context (urban, rural), taking into account the size of the group, the diversity of activity among group members, physical proximity among them, quality of leadership and the type of non-financial services proposed by the institution. In this respect, methods that favor training and information reinforce trust and create social capital. As shown in several case studies (Gloukoviezoff, 2007), the «creation of social value is the most important characteristic of social organizations» (Barrera, 2007, p. 61), it is «the pursuit of social progress, by removing barriers to inclusion, helping those temporarily weakened or lacking a voice of their own and mitigating the undesirable side effects of economic activity» (Austin et al., 2006, p. 296).

CONCLUSIONS

Innovation as a complex social process has been performing for several years the task of facing the social difficulties to which various sectors of society are exposed. It has emerged as a systematic practice that places collective rather than individual results at its epicenter. In general, there is a regularity in the central aspects of the definitions that have been presented in this regard, although it is important to note the multiplicity and complexity of the proposals. All of them are directed towards the presentation of new solutions that the communities involved themselves develop to satisfy their needs and alleviate the broad difficulties they may present. This aspect gives it the dimension of being social both in its means and, more importantly, in its ends as well.

The different experiences that have been carried out express a variety in their manifestations being coherent with the multiplicity of definitions. These are interrelated with aspects at the theoretical level, which makes it possible to consolidate a referential framework of theoretical and methodological scope. In addition, there are approaches to measurement and evaluation indicators. Finally, the recognition of the different initiatives will allow a knowledge of their functioning by discerning their characteristics and ways of acting.

The aforementioned aspects lead the debate towards the recognition of a variety of experiences with open and flexible foundations that allow the identification of a range of initiatives whose importance lies in allowing the analysis to be located in a heterogeneity of practices and proposals that are articulated with different theoretical and methodological foundations. Nevertheless, there are, as mentioned above, regularities especially in their social purpose.

With peculiarities similar to those described for the SI, the heterogeneity of proposals and scopes of SE is broad. The studies that address the convergences between both proposals, even though the synergies between both approaches, already described, are clear, are not widely systematized in the published scientific literature. If it is a question of recognizing and determining similarities, the role of the social in their projection must be made very clear. A wide range of studies linking both proposals have been examined, which provided the basis and orientation for the present research as a frame of reference. These, in general, made clear the socially oriented objectives in economic activities, the innovation functions that SEIs develop as a performance exercise, and a now recurrent aspect, the collective orientation of the purposes of both proposals, specifically social welfare. In other words, both can be oriented towards social needs.

The determination of the predictors as a result of the present research made it possible to consolidate the conceptual framework that interrelates the SI in SEIs, and to specify the variables that make it possible to measure how the three units of analysis of SEIs in the city of Ibarra, selected for the study, meet social needs by providing innovative solutions that account for their capacity to develop SI.