INTRODUCTION

Cuban Higher Education has initiated a process of transformation of the teaching of English since 2015. In organizing this process, a new policy was introduced. This policy's main purpose is to raise English competence in all Cuban university graduates through establishing an independent user (threshold) level (B1) according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, and Evaluation (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001) as an exit requirement for all university students.

The implementation of the new language policy in Cuban Higher Education implies the need for a reliable and valid certification system. Considering that in Cuba education is free, it was not possible to use any of the existing proficiency exams in the world, since they are not. Therefore, a Cuban Language Assessment Network in Higher Education (CLAN) was created to design a proficiency exam based on the CEFR and at the same time contextualized to the Cuban reality and needs. The CLAN is composed of experienced and young professors from all Cuban universities that assumed the conception of a project in 2017. This project is led by the University of Informatics Sciences, guided by an expert member of the European Association of Language Testing and Assessment, who is at the same time the Director of the Language Centre from the University of Bremen in Germany. The project also receives support from the Ministry of Higher Education, the VLIR ICT for Development Network University Cooperation Program, and the British Council in Cuba.

Within the project and CLAN labor has been the design of specific tasks for assessing each of the four main language skills, as well as the rubrics for evaluating productive skills. In this opportunity, the focus will be on one of the productive skills: speaking. The process of deciding and producing the tasks for evaluating speaking went through different stages. First, there was a process of assessment literacy for all members; once they got familiar with the theory and were able to manage the necessary terminology the conditions were ready for writing the Test Specifications and the item writer guidelines. Both documents were essential for designing the tasks and the rating scale. These two last aspects constitute the main focus of this paper, therefore, the purpose will be to describe the results achieved so far in the design of the tasks to evaluate English speaking skill and their corresponding rating scale.

METHODS

As mentioned already, this research relies on empirical and theoretical methods from a mixed-methods perspective, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches

1.1 Task design

Among the three challenges mentioned by O’Malley and Pierce (1996, p. 58) that teachers face when assessing oral language are: selecting assessment activities and determining the evaluation criteria. It is also necessary to consider that compared with the other skills, speaking is the most difficult to assess (Taufiqulloh, 2012). Taking this statement as a premise, in this research process theoretical methods were used; among them were the historical-logical, to determine different approaches and tendencies applied or followed by experts in other environments when contextualizing the CEFR and aligning a test to it. Likewise, the analytical-synthetic method was used to find out the regularities and most appropriate ways to carry out the study from the existing theory and practice.

Based on the Test Specifications and the Guidelines for developing and evaluating speaking tasks made by the CLAN, the speaking tasks were designed to meet the needs of higher education graduates in Cuba. Carroll & Hall's (1985) steps in designing an oral test were also considered. Furthermore, the tasks must be built on a valid, reliable, and practical speaking test. After several workshops where the project members went through an intensive training period, the speaking test was made up of three sections: 1) an interview, which is an interaction between the interlocutor and the test takers; 2) an interaction between test-takers (interviews, discussions, role-plays, problem-solving tasks); and a monologue (presentations, storytelling, reports, descriptions) with follow-up questions.

1.2 Rating scale design

An iterative approach (Piccardo, North & Goodier, 2019, p. 28) was followed for developing, validating, and revising the rating scale. This approach was also used by Harsch & Martin (2012). The methodology used for validation considers the three-phase mixed methods approach (qualitative and quantitative) described by Creswell (2009). Firstly, in the intuitive phase (North & Piccardo, 2017), as it is stated in the CEFR: “intuitive methods do not require any structured data collection, just the principled interpretation of experience” (Council of Europe, 2001) a team of six raters reviewed different rating scales designed for well-known international exams: Aptis Speaking rating scale (Fairbairn & Dunlea, 2017), the IELTS speaking band descriptors (British Council & Cambridge Assessment English, 2018) and TOEFL Independent Speaking Rubrics (Educational Testing Service, 2019). The Pearson Global Scale of English Learning Objectives for Academic English (Pearson English, 2019) and the CEFR Companion Volume (Council of Europe, 2018) were reviewed as well; in fact, this last document was the main reference used. These scales were selected because they have been consulted and used as a reference by most of the professors of English in Cuban universities since the new policy began. After reviewing these existing scales, a process of selecting the descriptors that suited best the Cuban context was pursued, as well as, a process of adaptation and discussion about those descriptors.

Later, in the first round of the qualitative phase, a bigger group of raters (27) initiated the validation of those descriptors. The raters analyzed each of them individually and even used them in the first pre-trial for rating some students' performances (6), during the first attempt of task piloting. This is what has been achieved so far, the next step may include revision and reformulation of the descriptors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1 Speaking tests

The process of deciding the most suitable tasks to be used was based on the teaching experience of Cuban professors combined with international practice on this skill and the CEFR. The Ministry Policy stated as the lower level A2 and the maximum level B1, therefore the tasks must cover learning outcomes from these two levels. In the Test Specifications, it was explained the need to develop B1 tasks, but with instructions in such a way that A2 students also could work on them. Therefore, tasks should be designed to allow certifying A2 and B1, but the focus of tasks is on B1 (curricular aim). In this regard, tasks should drive the students’ performance to higher levels.

Another aspect to ponder was the kind of tasks to be used. One of the most important elements was to be consistent with the constructive alignment so that the students could be familiar with the exam task. This can be attained if those tasks are similar to the ones they usually do in the classroom. It is also a way to consider the cognitive factors that the CEFR describes to be influential on the "potential difficulty of a given task for a particular learner” (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 160). Task familiarity minimizes the cognitive load and may facilitate successful task completion.

Furthermore, the tasks should be of a communicative type and in this sense, the tasks created considered the personal, public, occupational and educational domains (Council of Europe, 2001) to cope with the students' needs. The types of tasks were conceived to be interactive (sections 1 and 2) and productive (section 3). In section 1 the students will face an interview (interaction with the interlocutor), in section 2 an interaction with another student, and in section 3 a monologue situation. According to authenticity, the tasks should reflect the target language use as much as possible, so the situations they will be involved in, must be as closer as possible to the students' reality. When deciding the possible topic areas to be presented in the test, it was agreed to divide them into the two main levels to be achieved by the students: A2 and B1. Accordingly, the A2 topics are general considering concrete everyday familiar topics accessible to a general audience. On the other hand, B1 topics are also general, but professional and academic topics are likely included. They should be accessible to a general audience including concrete and some abstract topics too. There are some topics regarded as a taboo that must not be presented in the tasks since they could distress students in the exam (e.g. religion, politics, death, sexuality, abuse, natural catastrophes, COVID-19).

Following the premises specified in the Guidelines, Interlocutor Guides (IG) were designed. This is an indispensable tool that helps interlocutors to guarantee homogeneity in the task structure at the time of the test administration. This document comprises a warm-up and the three sections of the exam, stating the follow-up questions to be used by the interlocutor when needed. It also assures the use of standardized clearly stated instructions for each section with the approximate time allowance for each task. Moreover, the IG leaves few chances for improvisation because all the possible questions should be provided in it (see tables 1, 2 & 3).

Table 1: Speaking test 1. Interlocutor Guide Speaking Tasks. Interview

| Speaking test 1 Interlocutor Guide Speaking Tasks | |

|---|---|

| Hello. My name’s … | |

| Part 1 (Interview) 5 min | |

|

|

|

| I would like you to ask questions to each other. Is that OK? | |

| Interview Questions | |

| CANDIDATE A | CANDIDATE B |

| Why do young people like to watch TV series? Do you like TV series or shows? Why? Can you briefly retell the plot of your favorite TV show? What’s your favorite TV show about? What is your favorite actor/actress like? Can you describe your favorite actor/actress? | What was your favorite movie as a kid? Why? When you were a child, did you have a favorite movie? Why did you like it? What are the positive and negative aspects of reality shows? What is your opinion about reality shows? Do you think that soap operas are created for a female public? Why or Why not? Are soap operas only for women? What’s your opinion? |

| Now let’s talk about music. | |

| What music do young people like to listen to? Do young people usually like rock music? Why? Compare the music you listened to when you were in high school and the music you listen to now. What kinds of music do you prefer? Give reasons in each case. | 4. What are the advantages and disadvantages of listening to music while doing your homework? 1.1. Do you like listening to music while studying? Why? 5. If you were a famous singer, what would you do? 2.1. Imagine you are a famous singer and describe a typical day in your life. Thank you |

Table 2: Speaking test 1. Interlocutor Guide Speaking Tasks. Interaction

| In this second part, you two will have a conversation. The cards explain the situation and everything you have to do. You have one minute to prepare yourself for the conversation. You cannot speak to your partner during the preparation time. You may take notes but you may not read during the interaction. | |

| CARD 1 | CARD 2 |

| It’s the 1st day of lessons and your professor of English gives you this situation. You just got back from the most exciting holidays of your life. You run into your best friend, who wants to know everything about it. Give your friend as many details as possible about this experience. Don’t forget to ask your friend about his/her holidays as well. | It’s the 1st day of lessons and your professor of English gives you this situation. The new academic course has just begun and you run into your best friend who got back from holidays and looks very happy. Ask him/her for as many details as possible about this experience. Then answer his/her questions about your holidays. |

| Thank you | |

Table 3: Speaking test 1. Interlocutor Guide Speaking Tasks. Monologue

| Now each of you will talk about a topic individually. The card explains the situation and gives you the instructions. You have one minute to prepare your presentation. You may take notes, but you may not read during the presentation. You should speak for about TWO minutes. | |

| CARD1 | CARD 2 |

| You have just graduated and you are at a job interview. Your interviewer who is from Canada wants to know about your personal and professional expectations. | You are participating in an English-speaking competition. You are asked to talk about your plans for next New Year’s Eve. |

| Candidate A Follow up questions | Candidate B Follow up questions |

| Where do you plan to live and work? Why? Is it important to you to have children? Explain. | What food and drink do you plan to prepare? What people are you going to invite or visit? |

| This is the end of your exam. | Thank you |

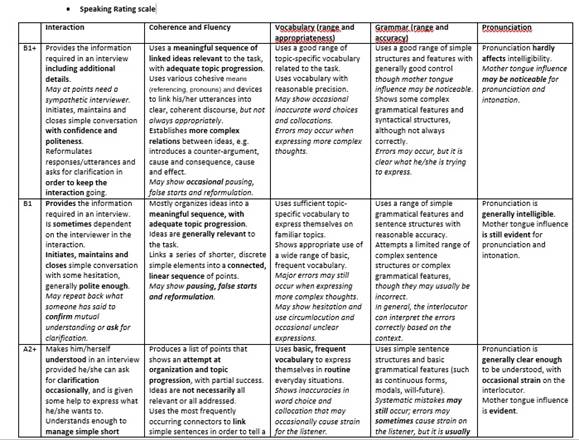

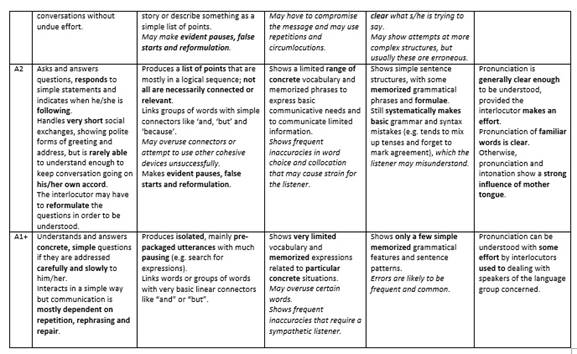

2.2 Speaking Rating Scale

The first decision made was to design an analytic scale (table 4) and table 5 that provides higher levels of reliability as students get several scores according to the different criteria (criterion-reference) (Nakatsuhara, 2007; Knoch, 2011). Besides, it carries more benefits from the pedagogical point of view (Hughes, 2003).

The next step was to determine the criteria and the levels to be included in the scale. This phase was carried out in group work and it was decided not to use the criterion task achievement (TA) as a separate criterion, considering that it differs for the different tasks; then it was included in other criteria descriptions. Finally, the criteria selected were:

Interaction: considering task achievement for role play, negotiation of meaning, turn-taking, keeping the conversation going; socio-linguistic & pragmatic aspects, fulfillment of goal (role play).

Coherence/fluency: considering task achievement for the monologue, organization, topic progression, development of argument, cohesive devices, also appropriately addressing the targeted audience, presentation skills (keeping eye contact, body language, 'making it interesting').

Vocabulary: considering range and accuracy.

Grammar: considering range and accuracy.

Pronunciation: considering stress, rhythm, and intonation

The decision-making on the levels to be included in the scale was determined by the Ministry Policy and the curricula learning outcomes: A2 and B1. However, during the construction process, it was decided to incorporate plus levels to "provide more guidance and precision without making the scale too granular” (Harsch, Collada, Gutiérrez, Castro & García, 2020, p. 89). In this sense, the scale covers levels from A1+ to B1+. It was a challenge to write a description for the plus levels since the CEFR was the main reference framework and doesn't describe these levels.

Once these two previous and cardinal elements were decided, a group of six raters revised existing rating scales to select the most suitable descriptors to the Cuban context and the ones that could be fulfilled concerning the curricula. The process of revision went through several sessions of group work, trying to identify the most relevant ones and at the same time adapting them when necessary. The CEFR Companion Volume (CEFR/CV) (Council of Europe, 2018) was taken as the main reference and some difficulties were faced within this process. There was a large number of scales at different places of the document. There were also different categorizations (i. e. the CEFR/CVs assessment grid categorization differs from the CEFR/CV scale system). Additionally, there was inconsistent wording across scales and/or across levels. It was found that some scales address similar aspects but use different wording in descriptors (Harsch et al, 2020). This process ended up with a preliminary scale that was subjected to modification in which some descriptors were created by the group of experts (mainly the plus levels).

During workshop 7, the first round of the qualitative phase took place. A group of 27 members of CLAN made a sorting activity with the descriptors designed. As the main achievement, there was a 100% coincidence among all the participants in identifying each descriptor against the five criteria. Nevertheless, when placing those descriptors in their corresponding level, the results showed some inconsistency. Most of them coincided in identifying the broad levels, but there was much more variance in the plus levels. In addition, the lower levels (A2 and A2+) were also difficult to place correctly, however, descriptors for levels B1 and B1+ were placed without too much trouble. These results, showed that there were misunderstandings of some descriptors due to their wording, in some cases the terms used were not completely clear for all raters, therefore, the next steps should be devoted to revision and reformulation of some descriptors.

CONCLUSIONS

The Ministry Policy of English in Higher Education has brought about hard work on assessment literacy for a great number of professors of English all over the country to be able to cope with the CEFR contextualization in Cuba. It has also opened a path on tasks design and rating scales development in Cuba.

This paper has shown the results got so far in the process of development of speaking tasks and a rating scale for English speaking assessment in Cuban Higher Education level. Within this process, a deep review of the existing rating scales, reformulation, and adaptation of descriptors have been carried out.

A task design and a rating scale development are processes that comprise several rounds of revisions until getting high-quality products. The creation of these two essential components for the Cuban Certification System based on the CEFR has proven to be an example of it.

Taking into account that this is a process that is still in progress, the next steps will be devoted to continuing with the design of new speaking tasks that will be piloted and assessed using the rating scale created which will be revised and improved. At the same time, a process of training professors all over the country will be also carried out