INTRODUCTION

Considering the pivotal role of English in the academic and professional settings on the one hand and the undoubted ineffectiveness of the programs implemented on the other, the Ministry of Higher Education (MES) decided to introduce a nationwide language policy in 2015 to drastically transform the teaching, learning, and assessment of the English language in Cuban HIGHER EDUCATION according to international language standards. Consequently, a project was formed in 2017: Cuban Language Assessment Network (CLAN), involving a group of teachers of English from all Cuban higher education institutions guided by Professor Claudia Harsch, assessment expert, vice president of the International Language Testing Association (ILTA) and head of the Language Center of the Universities in Bremen.

The major intentions behind the setting up of the project are: 1) “to develop a Cuban national certification system in academic English in Higher Education, 2) to enhance assessment literacy among Cuban language teachers in higher education, and 3) to pursue a research program about language assessment in Cuban Higher Education” (Harsch, Collada, Gutierrez, Castro & García, 2020).

In this regard, the principles of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001) were used to create appropriate instruments for building a common system for the teaching and assessment of the English language for the Cuban context, since “it provides a point of reference” (Canadian Association of Language Teachers, 2013). “The results show that the CEFR had a major impact on language education, especially in the field of curricula/syllabi planning and development”. However, “the CEFR impact is not confined to language teaching and learning only; its influence has extended to the realm of language assessment as well” (Shen & Wenxing, 2017). Since its publication in 2001, the CEFR has been the leading international reference, particularly for materials development and assessment in foreign language learning. “If a survey about the most relevant and controversial document in the field in the twenty-first century were to be carried out, the CEFR would most surely be the top one” (Figueras, 2012).

Nevertheless, since the earliest stages of the project it was envisaged that the network team should create a framework that would operate in the Cuban context. As Clark (1989) stresses, “what may be found suitable in one context may not necessarily be found appropriate in another”. This means that “in adopting the CEFR, modifications and adaptations are necessary to suit the local context” (Mohd & Nurul, 2017).

The Cuban framework was to be based on the CEFR, since “the CEFR is now recognized internationally as the standard language proficiency framework to adopt” (Mohd & Nurul, 2017). “One of the goals of the CEFR is to help stakeholders in the field of language education” (Canadian Association of Language Teachers, 2013) “to describe the levels of proficiency required by existing standards, tests and examinations, in order to facilitate comparisons between different systems of qualification” (Council of Europe, 2001). “It also clearly suggests planning backwards from learners’ real-life communicative needs, with consequent alignment between curriculum, teaching and assessment” (Council of Europe, 2018).

The CEFR has proved successful precisely because it encompasses educational values, a clear model of language-related competencies and language use, and practical tools, in the form of illustrative descriptors, to facilitate the development of curricula and orientation of teaching and learning (Council of Europe, 2018).

One advantage of the Cuban framework is that it was based on the CEFR Companion volume (CEFR/CV) (Council of Europe, 2018), which includes a number of modifications after frequent requests and critical observations concerning the CEFR 2001. The intention of the 2018 version “was to expand, clarify, and update it” (Foley, 2019). In addition to the new scales for language activities that were not covered in the CEFR scales published in 2001, the significant idea of uneven proficiency profiles or partial competence, which indicates that a language user’s proficiency is realistically uneven as well as its “can do” definition of aspects of proficiency, which focuses on what the student can do rather than on what the learner has not yet acquired, is also reflected in the Cuban adaptation. “This principle is based on the CEFR view of language as a vehicle for opportunity and success in social, educational and professional domains” (Council of Europe, 2018), which is noticeably compatible with the role of the English language in the Cuban Higher Education curricula.

Cuban framework basically proposes a scale of three English proficiency levels that covers from A1 to B1: Elementary English 1 (corresponding to CEFR/CV level A1), Elementary English 2 (corresponding to CEFR/CV level A2), and Intermediate (corresponding to CEFR/CV level B1). In other words, it starts with A1 (beginner or breakthrough) and progresses to A2 (waystage or elementary) to specify a basic user before reaching B1 (threshold or intermediate) to indicate an independent user. The goal is for Cuban university students to achieve a B1 level of English proficiency.

Even though the target level of the certification test is B1, at the present time, the required target level for Cuban university undergraduates is A2, since the Ministry of Higher Education decided to change the exit examination requirement during the term 2017-2021 owing to the lack of necessary resources, yet not assured.

The Cuban version of the CEFR/CV is expected to facilitate the implementation of the language policy syllabi, and improve the quality of the English teaching and assessment in Higher Education. Nonetheless, changes still need to be done before entirely implementing the contextualized version and attaining the Cuban proficiency certificate, since “teachers must be fully equipped and aware of the approaches to fully maximize the use of CEFR textbooks” (Nawai & Said, 2020). Equally, institutions must still assure teacher training to become accustomed to the CEFR impact in order to train students to be certainly competent and achieve the required target level.

Given that teachers of English at tertiary level education lack assessment literacy training, and therefore, experience in certification tests and standardized testing, a useful starting point of the project was to develop assessment literacy. In addition, various assessment materials have been produced, which include test specifications, item writer guidelines for the skills of listening, reading (which are called the receptive skills), speaking, and writing (which are known as the productive skills), together with templates for task development of the four skills, instructions for the receptive skills, interlocutor guides for speaking and rating scales for the productive skills.

As part of the project, the CLAN members have also cascaded assessment literacy knowledge in their institutions, collaboratively developed tasks in regional groups and received feedback on task development from each other; though further tasks are still required. In the next stages, improved tasks will be piloted at a national level for validity and reliability. As Alderson (2012) points out, “if an exam is not valid or reliable, it is meaningless to link it to the CEFR [and] a test that is not reliable cannot, by definition, be valid”.

Thus, this paper focuses on the process of developing receptive skills tasks aligned with the CEFR for the English proficiency certification in Cuban Higher Education. The task development process of the receptive skills is dealt with, including key aspects of the new assessment approach. Major challenges faced when developing listening and reading tasks are also discussed.

METHODS

Qualitative methods were chosen in the qualitative intuitive phase to develop assessment literacy and gain insights into theoretical and practical aspects of certification tests, including alignment with the CEFR as well as task development for the four skills. The expertise of participants, along with a collaborative responsive approach allowed developing basic documents for task development. Additionally, an iterative approach was used to develop tasks and feedback rounds in regional groups and during online working after the workshops.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

After eight workshops to date, a number of tasks have been developed aimed at attaining the main goal of the project, which is “to develop a teaching and certification system for English so that Cuban language centers can reliably and validly certify students’ English proficiency” (Harsch, Collada, Gutierrez, Castro & García, 2020). One of the ultimate goals of the project is to achieve international acknowledgment of the Cuban English proficiency certification.

The Cuban English certification test consists of four equally-weighing sections corresponding to the four language skills. Thus, both productive (speaking and writing) and receptive skills (listening and reading) are given the same prominence.

According to the test specifications for the Cuban proficiency certificate, the test is to certify proficiency at CEFR levels A2 or B1. Therefore, the general target level of the tasks is B1 CEFR, but also covering A2; meaning that students who cannot reach B1 can be certified as well.

In order to develop receptive skills tasks, in particular, we use the following materials:

the item writer guidelines for the skills of listening and reading-which describe the stages of the task development process

the templates for the listening and reading tasks-which include drop-down lists of options and checkboxes that allow test developers to identify the text and item characteristics

the instructions for the receptive skills-which provide standardized instructions for the task design.

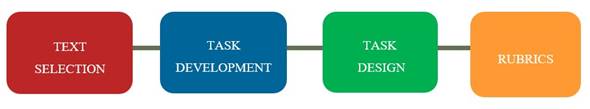

The stages of the task development process of the receptive skills can be seen in the figure 1 below. Each of these stages is then explained.

Text Selection

The selection of the text is the starting point for task development of receptive skills. In order to choose the appropriate text, we need to be concerned about specific text characteristics. Common characteristics to be identified in audio and written texts include authenticity, topic, grammar, vocabulary, nature of the content, level of difficulty, discourse type, the form of text, text input type /text type, length of input/number of words, and text source. Further text characteristics to be taken into account in audio texts encompass accent (i.e., varieties of international English accepted), number of participants, speed of delivery, and clarity of articulation.

Details of each text characteristic will be provided below.

Authenticity: A salient characteristic texts must have for listening and reading tasks is ´authenticity’; that is, all texts must be authentic, by which it is generally meant “material created by native speakers for other native speakers for communicative purposes in the world outside the classroom” (Clark, 1989, page 205). Hence, text selection for task development excludes those materials produced for language teaching purposes. In this sense, texts can be classified as authentic, adapted, shortened, simplified; depending on whether or not the text has been changed in any way.

Nevertheless, there are other equally significant aspects of authenticity that need to be stressed. “Two important aspects of authenticity in language testing are situational and interactional authenticity. Situational authenticity refers to the accuracy with which tasks and items represent language activities from real life” [whereas] “interactional authenticity indicates the naturalness of the interaction between the test taker and task and the mental process which accompany it” (Shen & Wenxing, 2017). “Authenticity itself is attractive to listeners/readers” (Kadagidze, 2006).

[However], for material to be authentic in the outside world, it must be relevant to listeners/readers. They must see some point in being asked to process the information in it (…) It is suggested, therefore, that material should be selected or created and treated to serve both ends. For this reason, listening and reading materials should be focused on meaning, be personally relevant, and serve some genuine communicative purpose. (Clark,1989, pp. 205, 206).

Topic: To select an adequate topic, it is important to keep in mind the students´ age group (18-24) at Cuban universities. Thus, we considered including a broad spectrum of general, professional, or academic topics accessible to the general audience such as technology, health/medicine, culture, environment, sports, agriculture, geography, biology and biotechnology, social life, humanity, music, education, professional duties, weather, art, language, history, sciences, and others; and decided to avoid those “potentially controversial or distressing topics that could affect students’ performance in an exam situation” (Harsch, Collada, Gutierrez, Castro, & García, 2020). Taboo topics include politics, religion, COVID-19, natural disasters, and so forth.

Grammar: As far as grammar is concerned, texts can contain only simple structures, a limited range of complex structures as well as complex structures.

Vocabulary: Suitable authentic materials for listening and reading tasks should include only frequent, most frequent and, rather extended vocabulary.

Nature of the content: The content of the texts can be classified as only concrete, mostly concrete, fairly extensive abstract, and mainly abstract.

Level of difficulty: Texts must be of a suitable level of difficulty (A2 or B1). Items with different levels of difficulty can be created from the same text, meaning that A2 items can be created from a B1 text trying to have an even spread of difficulty across A2 and B1.

Discourse type: Discourse is categorized into five broad types: narrative, expository, descriptive, argumentative, and instructive.

Text source: Websites, journals, encyclopedias, books, and newspapers can be used as text sources for reading tasks while the internet, podcasts, videos, live TV, radio, audiobooks, and live recordings are allowed for listening tasks.

Text input type /text type: Text input types encompass speeches, academic presentations, academic lectures, reports, monologues, narratives, conversations, and discussions. Text types, on the other hand, include articles, letters, emails, rewards, essays, blog entries, forums, advertisements, (simple) user manuals, instructions, tutorials, interviews, simple short articles, simple letters, personal emails, forum posts, simple short interviews and (series of) postcards.

Length of input /number of words: Audio texts should have a maximum length of four minutes (2-3 minutes for A2 level and 3-4 minutes for B1 level). Written texts, on the other hand, should include from 250 to 300 words for A2, and between 300 and 450 for B1.

Form of text: In terms of form, we take into account whether the written text is continuous or discontinuous (with diagrams, graphs, and charts, tables, pictures, bullets, or subtitles) and if the audio text is interactional (everyday conversations, informal interviews, etc.) or monological (clearly structured simple academic presentations, simple straightforward academic lectures or speeches, and so on).

Accent: Authentic materials for listening tasks can denote all sorts of international accents, but clearly intelligible; that is to say, all standard English accents: native British, native American, other natives as well as nonnative.

Number of participants: Listening inputs can include a maximum of three speakers as long as they can be clearly distinguishable. So, it was agreed that as far as possible audio texts with more than two participants or when their voices sound too similar should be avoided.

Speed of delivery: Audio texts should be slowly (100-140 wpm) or normally delivered (150-190 wpm), i.e. not too fast, not artificially slow.

Clarity of articulation: Bearing in mind the student´s language level, suitable authentic materials should be very clearly, carefully articulated, or normally articulated, but not artificially articulated.

Task Development

After selecting the suitable text, task developers have to decide which listening or reading behaviors the text lends itself to. At this point, we develop the questions which will lead to the answers by using mapping results to have a clear idea about what listening or reading behaviors task developers intend to test and choose the task and text/prompts accordingly. We must also select a task type that is familiar to the students who are to be tested, and avoid changing the item format within a single task. Task types for the receptive skills cover multiple-choice, short answer questions, multiple matching, ordering, filling in gaps with words/ sentences/ clauses, filling in diagram or table, and highlighting or underlining elements. Tasks must be accessible to the students' age group and must not be offensive, distressing, or violent. It is fundamental that the students can see easily how the task relates to the text, and that the time allocated for the task is sufficient for somebody who has the ability being tested to complete the task comfortably within the time limit.

Task Design

As far as task design is concerned, it was decided to develop standardized, brief, and clear instructions for the receptive skills. That is, understandable for A2 students so that the language used in the items and instructions is never more complex than that in the audio text or in the written text. It was planned that each task should have a minimum of five items, following the text sequence and evenly spread through the text. It was agreed that items related to the gist should be placed at the end and that all tasks must include a complete answer key providing all possible good answers. It is important that distractors in multiple-choice items are of similar length and structure. In short-answer questions, answers should be kept short, meaning that answers must have a maximum of five words. It was envisaged that misspelling must be acceptable unless it changes the meaning of the word.

Apart from the aforementioned aspects, special attention must be paid to the “not list” below:

Items must not elicit information from the first and/or last sentences, must not include verbatim information, and must not overlap. In non-sequencing tasks, items must not be interdependent, i.e., students should not need one answer in order to find another. In addition, two items must not have similar answers.

It must not be possible to answer any item without reference to the text. (This must be double-checked).

“Find the wrong answer” or “both are correct” type items are not acceptable in multiple-choice tasks.

Do not test vocabulary or grammar; do not use frequency adverbs, quantifiers, True/False items, multiple-choice with multiple correct answers or negative questions and statements in the items, and do not write tricky questions.

Rubrics

Lastly, with reference to rubrics, test developers must be aware of providing rubrics in English that are clear, simple, and brief as well as avoiding redundancies, exclamation marks, and metalanguage. So, rubrics need to be conformed to standard rubrics and indicate clearly what students have to write and where.

From the stages of the task development process, it was shown that the documents produced for task development facilitated the development of receptive skills tasks. Thus, serving as a guide for task developers to identify the text and item characteristics, and providing standardized instructions for the task design. The results further showed that the selection of the appropriate text helped not only decide which listening or reading behaviors the text lent itself to, but also choose the most suitable task types. It was found that the largest part of the authentic materials utilized for task development were articles, clearly structured presentations, narratives, and monologues. Technology, sports, health/medicine, environment, social life, education, culture, and languages were acknowledged to be the topic areas generally chosen from internet sources. In addition, most of the appropriate texts were mostly concrete, continuous, expository /descriptive/ simple argumentative or instructive, with most frequent or rather extended vocabulary, and a limited range of complex structures.

On the other hand, when developing receptive skills tasks we faced different challenges, and the major ones are mentioned below:

1) avoiding the use of pedagogical materials: Since texts must be authentic, we were confined to select materials from the “real world”. This created major challenges for task developers if we take into account the local technological constraints, as authentic materials had to be primarily taken from internet sources.

2) poor technical quality of recorded materials: The fact that audio materials are not always of a very good technical quality represented a fundamental issue related to listening tasks since it is important to select materials with minimal technical background noise to avoid affecting the quality of the listening task performance.

3) low-level match of authentic materials with the task level: It was commonly difficult to select authentic materials matching with the task level because they were often too long. Hence, it was necessary to shorten or simplify them so that the materials matched with the suitable length or number of words. It was also noticed that the clarity of articulation of most authentic materials was incompatible with the task level. Given that authentic materials are produced by native speakers for other native speakers, they are generally difficult to comprehend for A2 or near B1 students because authentic materials are usually not very clearly or carefully articulated. Thus, the main focus of our consideration was not only the level of the authentic material itself but the student´s language level as well.

4) unsuitable format of listening inputs for the local context: We frequently found suitable materials in video format for listening tasks. However, they needed to be converted to audio recording, as it is more complicated to use video materials in the local examination settings due to the lack of adequate infrastructure. To deal with these drawbacks, it was decided to record as far as possible native English speakers that were studying at the Technological University of “Havana José Antonio Echeverria” (CUJAE), who were kind enough to give spontaneous talks for listening tasks. For further tasks, as well as using internet sources, audio texts will be also created with the help of other English users, since a nonnative accent is also acceptable.

5) familiarizing with the new assessment approach : The other big challenge was getting used to the new assessment practice since we were unfamiliar with specific aspects of the CEFR approach, which display contrasting views with our traditional assessment practices. During hands-on sessions for task development, for example, it was found problematic to evade items with verbatim information, and avoid eliciting information from the first or last sentences of the text as well as providing items that always served the purpose for the student to process information. It was also demanding to elude negative statements in the items, and to provide short answer questions as well as multiple-choice items with the same length, given that we had to be concerned about keeping answers short and providing distractors with similar length and structure.

In short, it was shown that the selection of authentic materials was not only affected by the level of difficulty of the material itself but by the task level as well. As a whole, task development of the listening skill proved to be more troubling, since the choice of authentic materials was a problematic and complicated issue. The results confirm that external factors like the local context also need to be considered in order to identify particular issues, and therefore to seek effective solutions to them. Together, these results provide important insights into practical aspects of the task development process of the receptive skills for the Cuban certification test.

CONCLUSIONS

The CEFR provided the basis for building an adequate framework and a coherent system for the teaching and assessment of the English language for the Cuban national certification in Higher Education.

The various assessment materials produced using the CEFR as reference were crucial to ensure the development of listening and reading tasks in accordance with international standards to certify students’ English proficiency in Cuban universities.

Although a number of reading and listening tasks have been developed by the CLAN members thus far, further practice and tasks are still desirable. This also means that the issues that can emerge from the task development process must be properly identified and addressed to overcome them.

The challenges faced allowing task developers not only to recognize which aspects must be paid special attention to when developing receptive skills tasks but also to get used to the new assessment approaches.