Introduction

The armed conflict in Colombia has left indelible marks on society, particularly in the lives of women, who have disproportionately faced the ravages of war, mainly due to the constellation of roles they occupied. 1 The historical dynamics of the conflict, its escalations, recessions, and specific territorial configurations demand exploring how violence and displacement have affected not only the physical health but also the psychological and social health of Colombian women. 2

Colombia has been the scene of one of the longest armed conflicts in the world, dating back to 1964 and subject to various pacification strategies until the signing of the Peace Treaty. The confrontation also stood out for the diversity of forces in conflict, involving multiple armed agents, from guerrillas to paramilitary and state forces. Rural populations, especially women, were “trapped” in power dynamics that included neoliberal and extractivist models, illegal crops, and forced incorporation into war. 1,3)

Consequently, the conflict has transformed the social fabric and has significantly impacted the daily life of its citizens, not only due to the direct consequences originating in services but also due to the deterioration of the worldview and identity of Colombians. 4) Women, in particular, have suffered the consequences of this conflict in complex and multidimensional ways, mainly related to the degradation of their representation and the limitation of their agency. 5,6)

Gender-based violence, fundamentally sexual violence, was used as a weapon of war, affecting the integrity and dignity of countless women and girls. 7 Furthermore, forced displacement relegated many to marginality, both in urban centers as well as in rural areas. This scenario occurred as a system of limitations regarding access to quality basic services and development opportunities. 8,9

Despite the government efforts of different administrations, women were exposed to contradictions between political discourse and its implementation; just as they saw their diversity made invisible due to the non-distinction of race, ethnicity, and identity 10 Likewise, during the conflict and especially in the peace-building process, they had to deal with pejorative characterizations under labels such as victim, combatant, or caregiver. 11 Furthermore, this characterization was frequently subject to gender stereotypes and power structures that directly impacted their possibility of leading a dignified life and the free development of their personality, two recognized fundamental rights and the center of gender activism in Colombia. 12)

In this context, the research carried out sought to delve into the biopsychosocial effects of the conflict, with special emphasis on how adversities affect the health-illness process of women entrepreneurs. In that order, the effects of prolonged exposure to stressors, the nature of trauma, the structuring of disorders, and resilient behaviors were examined in the face of reintegration through entrepreneurship and the reconstruction of life projects after the conflict.

In order to achieve a comprehensive approach, the objective was to analyze the consequences of conflict on women seeking to rebuild their lives through entrepreneurship. Therefore, the intersection between conflict and the health-disease process was simultaneously explored according to its influence on social and community support networks.

This critical perspective was central during the study, not only by providing certain theoretical guidance to an eminently inductive proposal, but because it facilitated the construction of the meanings and meanings given by women to their undertakings in a context of transition, peace-building, and search for new forms of normality.

Methods

Approach and design of the study

In accordance with the epistemological orientation of critical theory and in order to grasp the essence of the representation of the entrepreneurial woman about the psychosocial consequences of the conflict, a qualitative approach was used. However, due to the uniqueness of the life trajectories of women entrepreneurs during and after the conflict, as well as the different types of economic activity chosen, it was decided to go beyond the descriptive scope and generate a theoretical approach.

In this sense, an emergent grounded theory study was designed, guided by saturation and theoretical sampling. Although the exploratory approach was maintained and a substantive theory was not reached, so the data collected was processed to build a platform for future research, as this study was part of a broader project.

Context and sample

The context of the study was the Department of Caquetá, Colombia. Specifically, we worked together with various initiatives to promote entrepreneurship, where custodians from different organizations were requested to collaborate to identify possible key participants. Once the first women to be interviewed were identified, they were asked for their recommendations for the inclusion of new participants. The sampling process occurred progressively and intentionally, considering knowledge gaps, participation availability, partial results, and saturation. In this sense, snowball sampling was employed as a strategy.

As criteria for selecting the sample, it was established that the participants had to be women affected by the conflict in at least one of the dimensions of the study, who had started a business or had joined one. The final sample was 16 entrepreneurial women. Six were in the age range between 25-30 years (n=6), eight were in the age range of 31-42 years (n=8), and two participants were between 43-50 (n=2). Regarding entrepreneurships, only three participants created their own entrepreneurships related to food (n=2); while the rest were from different types of entrepreneurships as co-founders or leaders (n=13).

Data collection

Based on the usual procedure of grounded theory, the semi-structured interview was used as the main data collection instrument, which was divided into dimensions and indicators to cover life during the conflict, consequences of the conflict in the various spheres of life, decision-making and start of entrepreneurship and future life projection. These interviews were transcribed and processed as a hermeneutical unit in ATLAS.ti 9.0.

Two strategies were established in order to achieve an adequate triangulation of sources. The first was to include questions in the interviews that would facilitate the expression of opinions and experiences about the partial results so that a constructivist inclination was adopted.13 The second was to generate data through participant observation, rounds of debates between the authors, consultation with specialists, and comparison with the results of similar research.

Data analysis

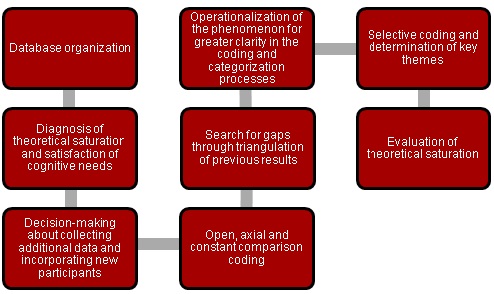

Data analysis was organized as a transectional and longitudinal process. The transectional analysis occurred at the end of each interview; an initial review was conducted aimed at achieving a general image of the data, note-taking and, at the beginning of the investigative process, the proposal of free codes. The longitudinal analysis was produced from the concatenation of the individual analysis and the application of open, axial, and constant comparison coding procedures. Finally, from these data, the main themes were generated, and the main relationships contained in these were represented using matrices. (Figure 1)

Ethical principles

As a fundamental ethical principle, it was established that women should voluntarily choose to participate and sign an informed consent form. In addition, participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the research, confidentiality, and data protection procedures.

Results

The database analysis yielded a total of 29 basic codes, organized and linked through 12 main codes or categories. In addition, two high-ranking categories were identified due to their co-occurrence and importance in the thematic analysis. Finally, three themes were constructed that allow us to understand and, in the context and sample of the research, partially explain the biopsychosocial consequences of the historical conflict on entrepreneurial women.

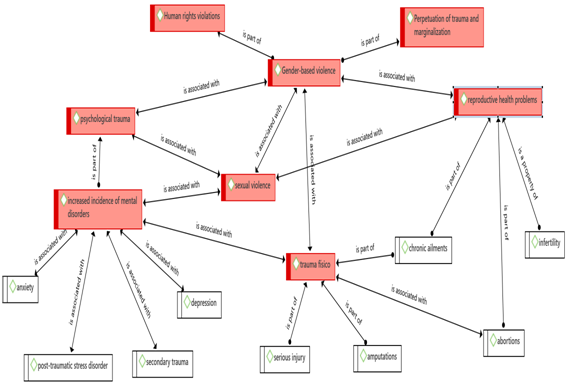

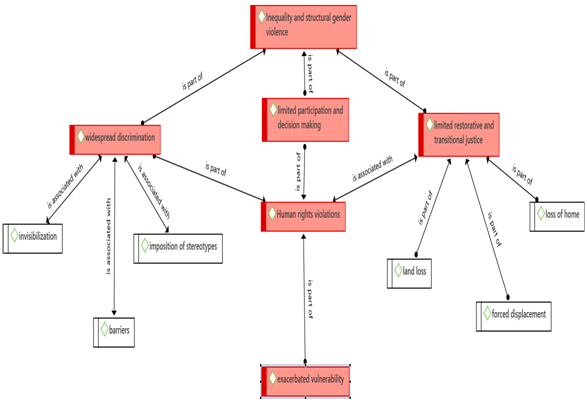

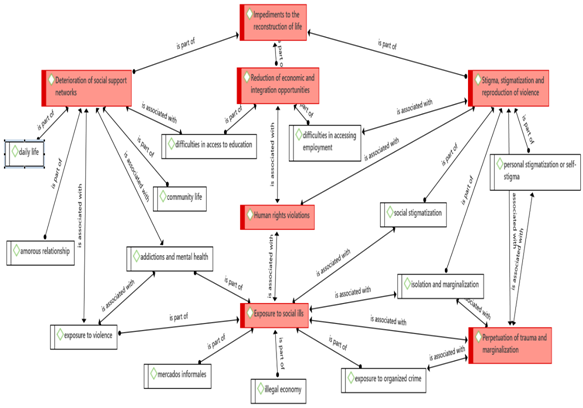

Below is a summary of the topical analysis, as well as its corresponding representation. In order to achieve a greater degree of clarity, a color system was developed, where the high hierarchy categories by co-occurrence were marked in red (n=2), the central categories of the topic in blue (n=3), the codes main codes in green (n=12) and the basic codes were left uncolored.

Gender-based violence and the health-disease process

The study carried out highlighted the prevalence of gender-based violence as a critical component in terms of entrepreneurial intention and the development of future plans. Although the codes frequently appeared disjointed in the discourse, the thematic analysis revealed deep and lasting implications for the health-disease process of women entrepreneurs.

The stories, as well as the opinions offered about the results, highlighted that different forms of violence, particularly sexual violence, were systematically used by armed agents as a tool of control and domination. Even in stories about third parties, it could be seen that these mechanisms served to perpetuate power and fear within the communities. The main consequences related to entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurship were fear of interacting with others, anxiety about procedures due to mistrust in institutions, and symptoms such as unstable mood, difficulty concentrating, and sleep-wake cycle disturbances.

Regarding the use of sexual violence as a strategy during the war, the entrepreneurial women reported its use as part of torture, intimidation, and reduction to objects. Among the main consequences were “psychological trauma” and diagnoses of post-traumatic stress. However, the analysis of codes and categories made it possible to connect these individual experiences to the perpetuation of trauma and marginalization, especially during the promotion of entrepreneurship.

A cardinal result of the analysis of this topic was that these acts, described as “brutal”, did not occur as isolated attacks, but as part of a widespread and habitual practice. The effects of such prolonged exposure to violence included a wide variety of mental health disorders, physiological disturbances, and serious injuries. Precisely, when analyzing the determinants and barriers of the intention to open or join a business, these “health problems” occupied a central place. This finding is fundamental because it establishes that the perception of health is a key factor in the recovery and reintegration process of women.

Furthermore, in this topic, an important connection was identified between the health-disease process, gender-based violence, and the violation of human rights. The relationship between codes and categories revealed that stigmatization caused by the visible and non-visible consequences of the conflict exacerbated isolation. When asked about the impact of such isolation on their lives, women pointed out the difficulty in seeking and receiving help.

The data analyzed pointed to the need to address these issues with an approach that recognizes the complexity and depth of women's experiences. Additionally, the examination of experiences showed that interventions targeting trauma symptoms were the most common but did not foster a supportive and empowering environment for survivors.

Therefore, the integration of specialized and accessible health services as part of post-conflict aid and reconstruction programs could be established as an essential need. In addition, it must be ensured that these services are prepared to treat the specificities of trauma related to gender-based violence in contexts of armed conflict while, at the same time, being linked to initiatives external to the health sector. (Figure 2)

Effects of the armed conflict on women's entrepreneurship

Regarding the impact of the armed conflict on the development of female businesses, the interviewees described significant repercussions, especially with regard to the creation and sustainability of businesses, as well as their participation in the local economy. In this sense, the analysis showed the impact on the economic and social participation of women, mainly in the context of the post-conflict.

The focus on entrepreneurship not only emerged as a result of the interviews but also emerged from the constructivist aspect of the analysis by linking mental health conditions to the daily life of women, fundamentally suicidal ideation as a result of hopelessness. Additionally, at a psychological level, a notable relationship could be observed between the health-disease process, the intention to undertake, and the cosmovision and symbolic aspects associated with the conflict, such as land, security, food, family, and home.

The interviewees outlined this relationship between the symbolism of the conflict and the health-disease process through the limitations and precariousness suffered, the discomfort generated, and the contradictions pointed out regarding whether entrepreneurship was a “way out” or not in the context of restoration and transitional justice. This vision, although frequently disconnected at a discursive level, showed the psychosocial and infrastructural envelope of salutogenesis and pathologies so that, even if the consequences were perceived as isolated, they were finally connected by the entrepreneurial women through the story.

One of the most palpable effects of armed conflict on women's businesses was the forced displacement of communities, which not only caused the loss of productive resources. As could be seen, the codes related the past and the future in the figure of displacements, with the collapse of existing enterprises as an “almost certain possibility”, despite the lack of data that supports this perception. Other similar irrational ideas were observed in connection with analogous processes.

Among the most mentioned limitations that still conditioned the lives of the entrepreneurs were insecurity and mobility limitations, as well as difficulties in accessing markets, suppliers, and resources necessary for their businesses. These conditionings were among the causes indicated by those interviewed to explain traumas and disorders. Likewise, these limitations were mentioned in relation to their perceived limited ability to make business decisions and manage their businesses.

In this sense, women entrepreneurs pointed out how generalized discrimination was one of the main effects of their association with the conflict. Through descriptors such as victim, ex-combatant, peasant, displaced woman, or others with a pejorative nature, women were not only forced to relive traumas, but barriers were imposed on their access to services and resources.

Among the most notable examples were limited access to financing and training. Some participants even acknowledged that, although there were support programs, this was their first experience. Among the reasons attributed, issues related to restorative and transitional justice reappeared, as the participants argued that, if they could not recover houses or land, they would not be able to access financing and training.

However, when asked about the benefits of the program for their general well-being, the women initially highlighted the strengthening of their entrepreneurial skills but also highlighted the importance of promoting new businesses and generating support networks through entrepreneurial ecosystems. According to the women interviewed, the benefits were palpable in terms of health, mainly by relieving symptoms of anxiety and depression, but it also helped them think about the future and rebuild their lives.

The verbalizations examined in this topic and the relationship between the categories placed barriers as a basic code, but whose importance is connected to the well-being of women through another code that is relatively isolated in terms of relationships, but cardinal due to its frequency and importance. In this regard, the results indicate the need to identify and eliminate the structural barriers that limit women's participation in decision-making and divide their fundamental rights, the latter aspect being central to the health-disease process. (Figure 3)

Entrepreneurship, resilience and the new normal

Despite the adversities imposed by the prolonged conflict, the women highlighted the importance of resilience as a fundamental pillar for reconstructing their lives and communities. In this sense, the women interviewed did not directly define resilience as a response or a capacity that conditioned the resulting improvement in the ventures. Instead, their narratives were marked by setbacks and a marked self-stigmatization process that reproduced the very stereotypes analyzed previously.

This advance allowed us to once again explore co-occurrences and assess that the perpetuation of trauma not only occurred at a social level but also from the women's own subjectivity. Therefore, it was assumed that psychosocial interventions could not be limited to the immediate needs of the victims through remedial approaches, but rather should promote empowerment processes as participants in the construction of peace.

When analyzing the causes exposed when assessing resilience from this perspective, past limitations were found related to education, social and community support networks, overexposure to social wrongs, different types of gender-based violence, and scarce opportunities for social reintegration. Therefore, resilience appeared more as a resistance behavior than as one based on emotional intelligence and the search for well-being. One aspect that was mentioned was motivation, which, in colloquial terms, was used to explain how the conflict and its consequences had acted on the determination to “move forward”.

As could be seen, the trauma was not only classified as psychological, but reference was also made to past experiences of the experiences of others, not only women. Therefore, among the successful initiatives in which they participated directly or heard about them, they included community activities to promote social cohesion, the development of leadership skills, and courses on rights and legal foundations. Although not all of these supports were specifically aimed at women entrepreneurs, they did value the strengthening of autonomy, active participation, and the promotion of a culture of peace and reconciliation.

This result was fundamental since its assessment indicates that a comprehensive approach must help rebuild the social structure damaged by the conflict, guarantee that women are not only symbolized as victims of the conflict, as well as support their transformation as agents of change. These ideas were confirmed when analyzing the representation of the topic, the consequences of systematic exposure to factors such as organized crime, the proliferation of informal markets, the production of illicit crops as a form of subsistence, the culture of violence as a way to resolve conflicts and marginalization were observed.

Finally, both in the saturation analysis and in the last interviews, it was possible to verify that the health-disease process constituted a fundamental determinant in the personal development of the female entrepreneur. Although the elements of health and disease traditionally conceived from the biological perspective were analyzed, the determination exercised by subjective, social factors and their own unique interrelation was also observed.

Two fundamental lines, both for their expression in symptoms and disorders, and for their relevance in the discourse and motivational structure, were the violation of human rights and the configuration of trauma. The importance of these two lines was that they facilitated the articulation of concepts from different fields, such as symptoms, symptomatology, fundamental rights, dignity, life projects, and resilience. This result was transcendental when understanding the biopsychosocial nature of the effects of conflict on women and, especially in their intention and entrepreneurial activity. (Figure 4)

Discussion

The armed conflict in Colombia has had a devastating impact on the infrastructure and delivery of health services, with especially serious consequences for women.14 The regions most affected by the conflict have historically suffered from notable shortages of medical personnel and essential resources, which has significantly hindered access to basic and specialized medical care. Furthermore, this deficit has been exacerbated by the physical destruction of medical facilities and the forced displacement of health professionals due to threats or direct attacks.

Additionally, health funding has experienced severe constraints, as much of the national budget has been redirected toward security efforts and military operations. This inefficiency in fund management has limited the ability of the government and non-governmental organizations to maintain and expand necessary health services. In particular, health programs aimed at women, including those focused on reproductive health and support for victims of sexual violence, have seen their funding reduced, reducing their reach and effectiveness, despite the strengthened legal framework and humanitarian aid received. 14)

The interruption of essential medical services has had a disproportionate impact on women, who often require specialized care related to maternity, reproductive health, and the consequences of gender-based violence. Lack of access to these critical services has increased risks of maternal morbidity and mortality, and exacerbated mental health conditions among conflict-affected women. 7,15)

Furthermore, the results of the study imply that limiting the health-disease process to medical variables constitutes a reduction in its complexity. Therefore, not only damage to health must be included, but also social factors that affect the well-being and dignified life of women. 15 Among the most prominent factors are structural and cultural barriers, the reproduction of stigmas, the lack of real support to promote female agency, and the generation of multidimensional strategies to support the construction of their life projects. 4,9

In the specific case of female entrepreneurs, this means developing effective strategies for skill development, resource management, building support, and mentoring networks, as well as training and knowledge transfer.11 However, in line with what has already been indicated regarding medical variables, promoting the well-being of entrepreneurial women is subject to the integration of economic, educational, social, legal supports and, fundamentally, focused on the free and dignified development of the personality.

Conclusions

The results obtained confirm the considerable impact of the prolonged conflict on the physical and mental health of women entrepreneurs. They also point to the need to reconceptualize the assistance offered to promote their integration into society and well-being.The development of specialized and accessible mental health services should be sought, and programs that comprehensively prepare women entrepreneurs for post-conflict interventions should be ensured, emphasizing equity and inclusion. Despite the inductive nature of the study, it is hoped that the analyses carried out will facilitate decision-making in the design of programs, strategies, and other supports necessary to address the diversity of experiences, ventures, and consequences of the conflict on Colombian women. Therefore, it is necessary to create teams that can move from multidisciplinary interventions to joint projects where the interdependencies exerted by the health-disease process are recognized, and the reconstruction of daily life is addressed based on entrepreneurship.