INTRODUCTION

Eugenia uniflora L. (Myrtaceae) is a tree species with ecological and economic importance. According to the New World Fruits Database (http://nwfdb.bioversityinternational.org)., this species is native to Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela. It is suitable for the reforestation of degraded areas, while their fruits are a source of feed for humans and the local fauna. Economically, E. uniflora is already employed by cosmetic companies and it has potential use in the pharmaceutical industry with attested anti-parasitic, anti-rheumatic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-kinetoplastidae activities (Auricchio and Bacchi, 2003; Costa et al., 2010; Cunha et al., 2016). Several secondary metabolites characterized as monoterpenes, triterpenes, flavonoids, tannins, and leucoanthocyanins (Cunha et al., 2015) are found in its leaves, which infusions are traditionally used against gastrointestinal disorders (Costella et al., 2013; Teixeira et al., 2016). Several secondary metabolites characterized as monoterpenes, triterpenes, flavonoids, tannins, and leucoanthocyanins (Cunha et al., 2015) are found in its leaves, which infusions are traditionally used against gastrointestinal disorders (Costella et al., 2013; Teixeira et al., 2016)

Ethanolic extracts of E. uniflora have been shown to inhibit Fe+2-induced lipid peroxidation and to scavenge free radicals, likely due to the high content of polyphenolic compounds such as quercetin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin, luteolin, and ellagic acid. However, harvest time, climatic conditions, and ripeness of the plant material may significantly interfere in the scavenging activity of the extracts (Cunha et al., 2016).

Seeds of E. uniflora are considered recalcitrant (Pilatti et al., 2011), and self-pollination seems to occur, but with less than 7.0% of fruit development (Diniz da Silva et al., 2014). Vegetative reproduction of E. uniflora through herbaceous cuttings is an achievable alternative for the clonal propagation of selected plants. However, the rate of rooting is low, ranging from 35.8 to 44.1% for cuttings derived from seedlings, while no rooting was observed in cuttings derived from adult plants (Lattuada et al., 2011). In vitro propagation studies for this species are scarce and have focused on the direct organogenesis from nodal segments and apical buds (Uematsu et al., 1999; Diniz da Silva et al., 2014 ). Similarly, studies concerning in vitro production of secondary metabolites are missing.

Aiming to provide a framework for the in vitro culture of E. uniflora, this study investigated the auxin/cytokinin-dependent calli induction and development in nodal segments, roots, and leaves of this species, as well as the somatic embryogenesis induction and production of polyphenolic compounds in calli culture in a liquid medium. Here we intended to answer three main questions: (1) Which are the most suitable explant and combinations of auxin/cytokinin for callogenesis induction and calli development in E. uniflora? (2) Are calli from nodal segments, roots, or leaves feasible for the induction of somatic embryogenesis route in E. uniflora? (3) Are calli culture in liquid medium an achievable method for the production of antioxidant compounds of pharmaceutical and cosmetic importance?

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Plant material

Ripe fruits were sampled from adult trees growing in the Atlantic Forest domain, southern Brazil. Seeds were isolated from the pulp and disinfected in an aseptic chamber by immersion in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 10 min, 1.5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 20 min, and then rinsed three times in sterile distilled water.

Seeds were individually inoculated in 150 × 25 mm test tubes containing 10 ml of agar:water medium (6 g l-1) and germinated into a growth room at 25 ± 2°C under a 16 h photoperiod with a 50 μmol m-2 s-1 irradiance provided by 40W/750 white fluorescent lamps, for about 60 days. These in vitro developed seedlings were used as the explant source for the callogenesis induction.

Callogenesis induction

Callogenesis induction was performed using MS basal medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with Morel vitamins (Morel and Wetmore, 1951), myo-inositol (100 mg l-1), sucrose (30 g l-1), ascorbic acid (10 mg l-1), citric acid (1 mg l-1) and different combinations of the auxins naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), and the cytokinins 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and Thidiazuron (TDZ), totaling eight treatments (Table 1). Preceding to sterilization by autoclave (120 °C, 1.2 atm for 15 min), the pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8, and agar (6 g l-1) was added for solidification. Filter sterilized ascorbic acid and citric acid solutions were added to the medium after sterilization.

Table 1. Treatments for callogenesis induction in nodal segments, leave sections and root segments of Eugenia uniflora.

Nodal segments (ca. 1.5 cm), leaf sections (ca. 1.0 cm2), and root segments (ca. 1.5 cm) were inoculated into Petri plates containing 20 ml of the induction medium and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C in the dark. Leaves were inoculated with adaxial or abaxial portions in contact with the medium. Visual evaluation of the explants was performed daily. Explants were transferred to fresh medium every 30 days.

Histological and histochemical analysis of the calli

Sections of nodal segments and leaves were fixed on the day cultures were initiated (day 0) and at days 5, 10, 15, 25, 35 and 60. Nodal segments and leaves were fixed in phosphate buffer 0.1 M (pH 7.2) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, at room temperature under vacuum for 24 h. Subsequently, the samples were dehydrated in an increasing series of ethanol aqueous solutions (30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100%; remaining for one hour in each concentration) and infiltrated with hydroxyethyl methacrylate resin (Leica Historesin), following the manufacturer recommendations. Detailed histological and histochemical analyses were performed only with calli from treatments T3, T4, and T6.

Transversal and longitudinal 5 μm thick cross-sections were obtained with a rotary microtome automatic advance (RM 2255, Leica). For histological studies, the obtained sections were stained with 0.2% toluidine blue O. The analysis and photographic documentation were carried out under a light microscope Olympus BX 41 equipped with Image Q Capture Pro 5.1 Software (QImaging Corporation).

Somatic embryogenesis induction

Calli were inoculated into Petri plates containing 20 ml of the induction medium and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C under a 16 h photoperiod with a 50 μmol m-2 s-1 irradiance provided by 40W/750 white fluorescent lamps (Litz, 1984; Salma et al., 2019). Somatic embryos development was evaluated after 15, 30, 45, and 60 days of culture. Evaluations were performed using an Olympus SZ2-ILST stereomicroscope under 40x-60x magnitude.

Antioxidant activity and production of polyphenols in liquid medium culture

Calli culture in liquid medium

Culture in liquid medium was established only with calli originated from nodal segments of treatments T3 and T4. Eight-week-old calli were detached from the correspondent plant tissues and transferred to 250 ml sealed Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml of the propagation medium, composed by MS basal medium supplemented with Morel vitamins, myo-inositol, sucrose (30.0 g l-1), 5 M NAA and 5 M TDZ (T3) or 10 M TDZ (T4). Approximately 1.5 g of calli were incubated into each flask. Cultures were incubated at 20 ± 1 °C in the dark under constant rotatory shake (100 rpm).

Quantification of antioxidant activity and polyphenols in calli cultures

The antioxidant activity of the cultivated calli and the quantification of antioxidant compounds was determined for the callus and the culture liquid medium using different approaches. For the quantification of antioxidant compounds, 1000 mg of calli, collected after ten weeks in culture, were individually crushed in 2.0 ml microtubes with 1.0 ml of distilled water, centrifuged at 28 000 g for 15 min and the supernatant was used to determine the antioxidant activity. Additionally, 5 ml of the liquid culture medium in which the calli were cultivated were collected for the quantification of the antioxidant compounds exuded by the calli. The antioxidant activity of fresh leaves extract (1000 mg of leaves in 1.0 ml of distilled water) of E. uniflora was also determined, aiming to obtain comparative parameters to the callus induced production of antioxidant compounds. All the spectrophotometric assays were performed in an Agilent Cary 60 UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Means of all measurements were determined after four to six replicates.

Scavenging activity towards diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radicals by the samples was assessed according to Baltrušaitytė et al. (2007). Radical scavenging activity was expressed as μM of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) per 100 mg of leaves extract, callus, or culture medium. The reducing capacity of the samples was assayed as Benzie and Strain (1996) through the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) test. The reducing ability of plant extract was expressed as μM of Fe(II) equivalent per 100 g of leaves extract, callus, or culture medium.

Total phenolics compounds were detected by the method of Folin-Ciocalteu (Singleton et al., 1998) with minor modifications as described by Teixeira et al. (2016). The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAEs) per 100 g of leaf, callus, or culture medium extract. The total flavonoid content was determined using the Dowd method, adapted by Arvouet-Grand et al. (1994). The results were expressed as mg of quercetin equivalents (QE) per gram of leaves extract, callus, or culture medium.

Statistical analysis

The software PAST 3.02 (Hammer et al., 2001) was employed to perform a two-sample paired t-test comparing the callogenic potential of nodal segments, leaves, and roots based on the percentage of explants with calli after 30 days in the induction medium. As data were expressed as percentages, they were previously transformed to arcsine (x/100)0.5, where x is the measured data. Treatments were compared for each kind of explant using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey test at 5%. The difference among treatments concerning the antioxidant activity and content of phenolic and flavonoid compounds was determined by comparing the means using the Tukey test at 5%.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Callogenesis induction

In vitro germination of starting plant material

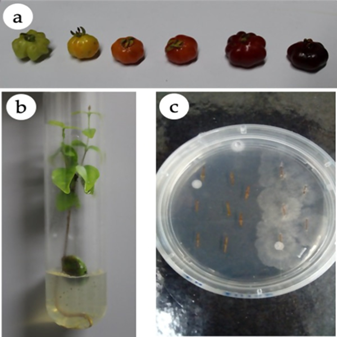

The in vitro germination of E. uniflora seeds (Figure 1 a) provided vigorous contamination-free plantlets (Figure 1 b) able to generate explants for callogenesis induction approximately 60 days after inoculation in agar:water medium. Bacterial or fungal contamination in the germination medium was observed in only 2% of the inoculated seeds, revealing the efficiency of this strategy in generating axenic starting plant material for callus induction.

Figure 1. In vitro germination of Eugenia uniflora. (a) Fruits of E. uniflora at different stages of development. (b) Axenic in vitro germination in agar:water medium. (c) Fungal contamination of explants from one plant, while the explants from another one, cultivated in the same Petri plate, have no contamination.

Although the propagation of E. uniflora through seeds has not been pointed out as a trouble for the establishment of nurseries and orchards of the species, protocols for in vitro mass propagation through somatic embryogenesis and for the production of secondary metabolites have several advantages. In vitro callus culture provides a contamination-free environment with controlled conditions of cellular growth, independent of climatic conditions, pathogens occurrence, or any other management problems of field cultures (Naaz et al., 2019).

Callus induction and proliferation

Although the starting plant material used for the obtention of the explants was germinated in vitro and it was absent of microbial contamination, endogenous bacteria and fungi arose in the induction medium after up to seven days of culture in around 20% of the inoculated explants. In such a case, non-contaminated explants were carefully transferred into new Petri plates with the corresponding induction medium. This kind of contamination was clearly of endogenous origin since, in the same plate containing explants obtained from different plants, bacterial and/or fungal contamination was usually observed only in explants originated from one plant, while explants from the other plant were completely free of contaminants (Figure 1 c).

In the induction media, the calli proliferation occurred preferentially in the basal region of the nodal segments, but also along the explants, in the axillary buds of nodal segments and the margins of the leaves. About seven days after the introduction in the induction medium, calli were already observed in the nodal segments of treatments T1, T3, T4, T5, and T6. Calli took around 30 days to be visible in leaf and root explants. Following this period, calli presented continuous development in leave sections, but not in root segments, in which the callus development was very slow. Callogenesis in leaf segments of Eugenia involucrata was reported by Golle and Reiniger (2013), corroborating the use of such kind of explant for calli induction. On the other hand, nodal segments of Eugenia species have been employed for direct organogenesis (e.g. Uematsu et al., 1999 Golle et al., 2012; Diniz da Silva et al., 2014). In this study, nodal segments of E. uniflora revealed to be a very efficient explant for calli induction under adjusted combinations of auxins and cytokinins.

Concerning the percentage of explants presenting callus 30 days after inoculation in the induction medium, the pairwise comparison of nodal segments vs roots, nodal segments vs leaf (both abaxial and adaxial) and leaf abaxial vs leaf adaxial presented significant difference (p<0.05). The use of roots as explants did not differ (p>0.05) from using leaves with abaxial or adaxial portion contacting the medium.

On the other hand, a large difference among treatments was observed concerning the callogenesis in each kind of explant (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean percentage of explants of Eugenia uniflora revealing callogenesis after 30 days in culture.

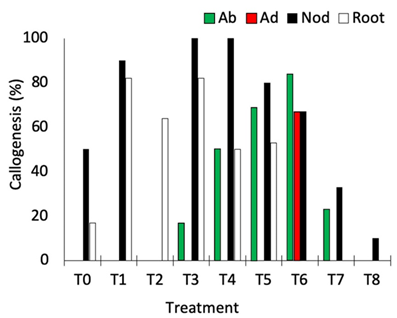

Nodal segments, leaves, and root segments showed enhanced callus induction in treatments, with the highest responsiveness observed in the treatments containing NAA (5 μM and 10 μM) + TDZ (5 μM) (T3, T4, and T6; Figure 2). Nodal segments presented the highest callogenic response to all treatments except T2 (10.0 μM NAA + 5 μM BAP) and T6 (10.0 μM 2,4-D + 5 μM BAP) (Figure 2). Leaves inoculated with the adaxial portion in contact with the medium only generated callus in treatment T6, while leaves inoculated with the abaxial portion contacting the medium showed callogenic response in treatments T3, T4, T5, T6, and T7 (Figure 2). This result is likely related to the histological differences concerning abaxial and adaxial portions of the leaves, as the stomata are present only in the abaxial epidermis of the leaves (Alves et al., 2008). In Eugenia involucrata, no significant difference was observed in the rate of callogenesis for leaves inoculated with the abaxial or the adaxial portion contacting the medium.

Figure 2. Percentage of callogenesis obtained in different explants of Eugenia uniflora cultivated under different combinations of auxin and cytokinin. Ab = abaxial portion of the leaf in contact with the medium; Ad = adaxial portion of the leaf in contact with the medium; Nod = nodal segment; Root = root segment.

Distinctly visible calli were observed after 30 days in culture according to the explant and plant growth regulator used. Overall, calli developed in nodal segments were slightly compact and white to light-yellowish, while compact light-brownish calli developed in the margins of leaves. Callus development in roots was much inferior and slower than in nodal segments and leave explants. Callus formation in plants is strongly associated with cell dedifferentiation, although callus formation should adequately be considered as a type of cellular transdifferentiation (Fehér, 2019). Moreover, transcriptomic studies support the interpretation that calli can be formed through different initial pathways which converge on the same gene regulatory network coordinating stress, hormone, and developmental responses (Fehér, 2019). Such cellular transdifferentiating as effect of the interaction among explant tissues and culture conditions (mainly the plant growth regulators added to the medium) results in diverse callus morphology, as well as distinct behavior in further development.

The combination of 2,4-D (5 or 10 μM) and BAP (5 μM), as well as using 10 μM of NAA only, was also efficient for callus induction in leaves explants of Eugenia involucrata promoting the callogenesis in 75% to 92.7% of the explants (Golle and Reiniger, 2013). The use of NAA + BAP (5 μM each) induced calli formation in cotyledons (74% of the explants) of Ugni molinae (Myrtaceae), while NAA only promoted higher calli induction in hypocotyls (94%) at a concentration of 2.5 μM and in leaves (80%) at a concentration of 5 μM (Beraud et al., 2014). In this study, the higher rate of callogenesis in leaf explants was 84% using 2,4-D 10 μM and BAP 5 μM. However, the callus induction using nodal segments was very efficient, reaching 100% of explants generating calli in treatments T3 (5.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ) and T4 (10.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ).

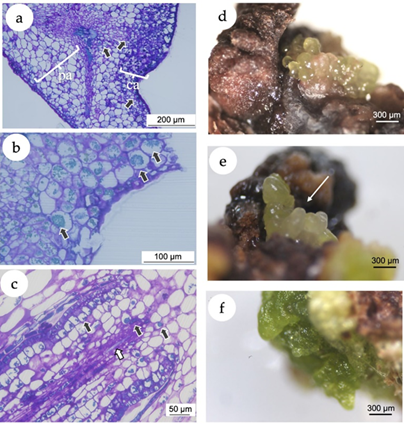

In the present study, the histochemical analysis revealed a clear difference between the explant and the callus tissues (Figure 3 a). A high accumulation of polyphenol vesicles in the explants was observed, mainly in the callus tissue as blue-greenish stained vesicles in the microscopic images (Figure 3 b). Even in calli putatively following a morphogenetic pathway (Figure 3 c), the presence of phenolic vesicles was evident. The induction of callogenesis is commonly a prerequisite for somatic embryogenesis (Gueye et al., 2009), while the accumulation of polyphenols in in vitro cultivated tissues has been associated with the somatic embryogenesis induction (Reis et al., 2008). In this sense, histological and ultrastructural studies showed that indirect somatic embryogenesis of Acca sellowiana (Myrtaceae) occurs in close association with phenolic-rich cells which, in more advanced stages of development, formed a zone isolating the embryo from the maternal tissue (Reis et al., 2008). Besides, in in vitro plant tissues, polyphenol compounds prevent hyperhydricity and are likely related to lignin synthesis (Cangahuala-Inocente et al., 2004).

Figure 3. In vitro callogenesis and induction of somatic embryogenesis in Eugenia uniflora. (a) Microscopic image of a section of the leaf segment showing the leaf tissue and the callus. The arrows point the phenolic inclusions, almost predominantly in the callus tissue. pa = parenchymal tissue of the explant; ca = callogenic tissue. (b) Microscopic image of a section of the leaf segment cultivated using 2,4-D (10 μM) + BAP (5 μM). Black arrows point the phenolic inclusions. (c) Microscopic image of a morphogenetic callus obtained from nodal segments cultivated using NAA (5 μM) + TDZ (5 μM), presenting early vascular tissue with phenolic inclusions (black arrows) and tracheids (white arrow). (d) Putative somatic embryos originated from calli induced with treatment T4 (10 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ) with isodiametric cells. (e) Putative somatic embryos originated from calli induced with treatment T4 with elongated cells (white arrow). (f) Green compact calli from treatment T3 (5 M NAA + 5 M TDZ).

Somatic embryogenesis induction

After 30 days of culture under 16-h photoperiod, calli originated from nodal segments of treatment T4 (10.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ) revealed the development of putative embryogenic structures with isodiametric (Figure 3 d) and elongated cells (Figure 3 e), with morphological structure similar to globular and torpedo stages observed in somatic embryos of the Myrtaceae species Acca sellowiana (Canhoto et al., 1996; Stefanello et al., 2005; Cangahuala-Inocente et al., 2009; Pavei et al., 2018) and Myrcianthes communis (Canhoto et al., 1999a). Calli from nodal segments of the treatment T3 (5.0 M NAA + 5 M TDZ) and leaves of the treatment T6 (10.0 μM 2,4-D + 5 μM BAP) did not develop somatic embryos but turned into green compact structures (Figure 3 f).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting somatic embryogenesis induction in E. uniflora. Somatic embryogenesis offers plentiful advantages over in vitro direct organogenesis of plants, including the large-scale production of plants with elite traits, generation of cell lines to conduct genetic engineering, basic functional and molecular research, and conservation of genetic resources by synthetic seed technology and cryopreservation (Salma et al., 2019).

Typically, somatic embryogenesis in species of the Myrtaceae family as Myrtus communis L., Acca sellowiana (Berg.) Burret., Psidium guajava L., Myrciaria aureana Mattos and Campomanesia adamantium Berg. has been induced using zygotic embryos as explants (Canhoto et al., 1999a; Cangahuala-Inocente et al., 2004; Rai et al., 2007; Motoike et al., 2007; Rossato et al., 2019). Despite the success of this procedure, zygotic embryos do not allow cloning the desired traits of elite adult plants. The procedure, presented in this paper, based on nodal segments as explant for the induction of somatic embryos has the advantage of enabling the clonal mass propagation of selected elite plants.

In Myrtaceae, the somatic embryogenesis has been induced mainly with auxin alone in the culture medium (Canhoto et al., 1999b). Using a combination of auxin (10 μM NAA) and cytokinin (5 μM TDZ), the procedure presented in this paper promoted the induction of somatic embryos in approx. 70% of the explants. The results were in accordance with previously reported for other species with the combination of plant growth regulators. For instance, in Eclipta alba (Asteraceae), a frequency of 80.17% of embryogenesis was obtained from calli cultivated in MS medium supplemented with picloram (2.0 mg l-1) and TDZ (0.5 mg l-1) (Salma et al., 2019). Similarly, Golle and Reiniger (2013) reported the induction of putatively embryogenetic calli in leaf explants of E. involucrata cultivated in MS medium supplemented with 2,4-D (5 μM) and BAP (10 μM).

Antioxidant activity and production of polyphenols in liquid medium culture

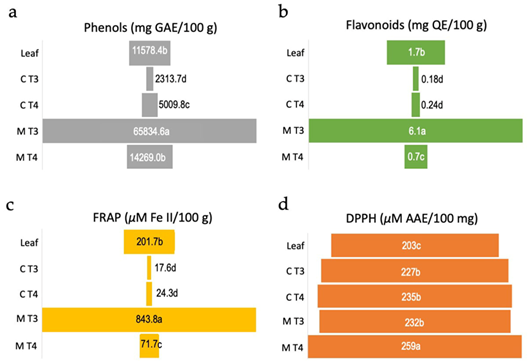

The culture medium of treatment T3 (5.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ) revealed significantly higher (p<0.05) content of flavonoids and phenols (Figures 4 a-b), and high reducing capacity in the FRAP test (Figure 4 c). Concerning the antioxidant activity based on DPPH scavenging activity, the culture medium of treatment T4 (10.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ) presented slightly but significantly higher (p < 0.05) values of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE) in comparison with culture medium of treatment T3 and to calli from treatments T3 and T4. The lowest value of AAE was observed for the extract of leaves (Figure 4 d).

Although E. uniflora has been widely studied concerning its medicinal potentials, this is a pioneer study investigating the in vitro production of polyphenols. Moreover, the most promising results regarding polyphenol production were obtained in the medium extract, which may simplify the purification of these secondary metabolites. While the main framework for callogenesis and calli culture were determined in this study, further investigations should focus on examining the growth kinetics of the calli and the detailed composition of the produced polyphenols.

Figure 4. Biochemical analyses of antioxidant activity of calli and culture media of Eugenia uniflora. Values are means over four to six replicates. (a) Amount of total phenolic compounds measured as mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/100 g of leaves extract, calli or culture medium. (b) Total flavonoid content measured as mg of quercetin equivalent (QE)/100 g of leaves extract, calli or culture medium. (c) Amount of reduced FeSO4 measured as µM of Fe(II)/100 g of leaves extract, calli or culture medium. (d) DPPH radical scavenging potential of leaves extract, calli or culture medium measured as µM of ascorbic acid equivalent (AAE)/100 mg. Leaf = leaves extract from field plant, C T3 = callus from treatment T3 (5.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ), C T4 = callus from treatment T4 (10.0 μM NAA + 5 μM TDZ), M T3 = medium from treatment T3, M T4 = medium from treatment T4. Means followed by the same letter within each test do not differ statistically at 5% according to the Tukey test at 5%.

Although cell growth in the calli culture in liquid medium was not measured in this study, cell suspension cultures are considered to display much higher division rates than intact plants. Besides, enhanced antioxidant activity and production of phenolics and flavonoids in suspension culture over wild plants have been reported for different species (Ali et al., 2013). There are numerous reports on the protective effects of natural antioxidants against oxidative stress-related disorders like aging, degenerative diseases, and cancer, and the antioxidant potential in several medicinal plants is essentially a result of phenolic compounds (Ali et al., 2013). Therefore, this approach is advantageous for the production of secondary metabolites of industrial importance (Pacheco et al., 2012).

The present report describes the establishment of a framework for the in vitro culture of E. uniflora. The obtained results shed light on the three main questions driving this study: (1) nodal segments are the most responsive explants and the combination of NAA (5.0 or 10.0 μM) as auxin and TDZ (5 μM) as cytokinin is the most suitable for callogenesis induction and calli development in E. uniflora. Leaf segments also generated calli with 10.0 μM 2,4-D as auxin and 5 μM BAP as cytokinin. However, the response of these explants was inferior in comparison to nodal segments, while roots are not suitable explants for callogenesis in E. uniflora. (2) Somatic embryogenic structures were obtained from calli induced from nodal segments cultured with 10.0 μM of NAA as auxin and 5 μM TDZ. (3) The culture of the calli in liquid medium supplemented with 5.0 μM of NAA as auxin and 5 μM TDZ promoted the production of high contents of flavonoids and phenols, arising as a suitable framework for in vitro production of secondary metabolites of E. uniflora.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provided a framework for callogenic induction in nodal segments and leaf sections of E. uniflora. The calli obtained from nodal segments revealed to be suitable for somatic embryogenesis establishment and the production of secondary metabolites with pharmaceutical potential. Based on these results, further studies can be performed towards the mass propagation of E. uniflora through the somatic embryogenesis route and the production of antioxidant compounds in liquid medium culture at a larger scale. Also, the occurrence of somaclonal variation in the regenerated plant progenies of the somatic embryos and the use of explants from adult plants has to be tested.

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI