Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de Ciencias Médicas de Pinar del Río

versión On-line ISSN 1561-3194

Rev Ciencias Médicas vol.27 no.3 Pinar del Río mayo.-jun. 2023 Epub 01-Mayo-2023

Articles

Protocol for the correct diagnosis and treatment of dengue fever in Pediatrics

1University of Medical Sciences of Pinar del Río. Provincial Pediatric Teaching Hospital "Pepe Portilla". Pinar del Río, Cuba.

Introduction:

dengue is the most important arbovirosis worldwide, considered as an emerging infectious disease. Our country does not escape from this reality. Children are undoubtedly among the most vulnerable age groups.

Objective:

to improve the action protocol for the correct diagnosis and treatment of dengue at the Provincial Pediatric Hospital of Pinar del Río.

Development:

the fundamental elements of the definition of a dengue case, evolutionary course of the disease, classification according to severity, positive and differential diagnosis, with emphasis on the timely treatment for the prevention of complications and death in pediatric patients with clinical suspicion are presented.

Conclusions:

this protocol does not replace the one approved by the National Pediatric Group, but complements and summarizes a series of aspects that are essential for the management of children with dengue fever.

Key words: DENGUE/etiology; PEDIATRICS; TREATMENT; CHILD

INTRODUCTION

Dengue is the arthropod-borne viral disease with the highest morbidity and mortality worldwide. Its incidence has increased in the last decades, which is why it is considered an emerging infectious disease and a global public health problem.1,2,3,4

In the Americas, dengue is the most important arbovirosis. The number of cases of this disease has increased exponentially, with epidemics occurring every three to five years. The most recent epidemic was reported in 2019, with more than 3,1 million cases. In September 2022, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) reported 2,493,414 cases of arbovirosis in the Americas region and of these, 90,2 % corresponded to dengue.5,6,7,8

Our country does not escape from this reality. Data from the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) report 3,036 cases of dengue in the first semester of 2022, with circulation of the four serotypes and high rates of vector infestation and high risk of disease for the entire population.9

Children are undoubtedly among the age groups most vulnerable to dengue. In pediatrics, this disease presents important particularities in its clinical course, related to the patient's age, associated comorbidities and situations that may constitute alarm signs.10,11,12,13

Although the disease is complex in its manifestations, treatment is relatively simple, inexpensive and very effective in saving lives, provided the correct and timely interventions are implemented. The key is early identification and understanding of clinical problems during the different phases of the disease, which allows a rational approach to case management and a good clinical response. It is significant to note how difficult it is to determine the differential diagnosis of dengue even for seasoned practitioners. (14,15,16,17

Taking into account the serious complications associated with dengue in pediatric patients and its incidence in the province, the present review was carried out with the aim of improving the protocol for the correct diagnosis and treatment of dengue at the Provincial Pediatric Teaching Hospital of Pinar del Río.

DEVELOPMENT

Definition of suspected case of dengue fever

A person who lives in or has traveled in the most recent 14 days to areas with dengue transmission and initiates sudden high fever, usually lasting two to seven days, and two or more of the following manifestations:

Any child coming from an area with dengue transmission or residing in such an area, with acute febrile symptoms, usually lasting two to seven days and without apparent etiology, may also be considered suspicious. (18,19,20

Description of the disease

Dengue is a systemic and dynamic infectious disease, which may be asymptomatic or have a broad clinical spectrum that includes severe and non-severe expressions. After the incubation period (seven-14 days), the disease begins abruptly. It may have three phases: febrile phase, critical phase and recovery phase (a minority develop the critical phase). 10,19

Febrile phase

Critical phase

If the period of shock is prolonged and recurrent, it leads to hypoperfusion and organ dysfunction, metabolic acidosis and consumption coagulopathy. (1,6,22,23)

Recovery phase

Classification according to the severity of Dengue

Dengue without alarm signs (Group A)

A patient who meets the definition of a suspected case and has no alarm signs.

Dengue with alarm signs (Group B)

Any case of dengue fever that presents one or more of the following alarm signs close to and preferably at the onset of fever:

Severe Dengue (Group C)

The level of care for the management of this group is the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU); it includes any case of dengue that has one or more of the following manifestations:

Table 1 Clinical problems in the phases of dengue fever. 10,16,23

| Phase | Clinical problems |

|---|---|

| Febrile | Dehydration; high fever may be associated with neurological disorders and seizures in young children. |

| Critical | Shock due to plasma extravasation; severe bleeding, serious organ involvement. |

| Recovery | Hypervolemia (if intravenous fluid therapy has been excessive). |

Complementary tests

Hematocrit, leukocyte and platelet counts are the recommended clinical laboratory tests on admission to the emergency department. Failure to perform these tests does not preclude initiation of the recommended treatment.

The rest of the complementary tests should be performed according to the patient's clinical picture and the treating physician's criteria.

Imaging studies (chest X-ray, ultrasound) are useful to evaluate the presence of free fluid in the abdominal cavity or in the serosa (pericardium, pleura), before they are clinically evident.

Echocardiography can be useful to evaluate pericardial effusion, in addition to assessing myocardial contractility and measuring the ejection fraction of the left ventricle, when myocarditis is suspected.1,13,24

Diagnosis

Dengue is an eminently clinical disease.

Direct methods

Days zero to five from the onset of symptoms (not currently available in our environment):

Indirect methods

From the 6th day after the onset of symptoms (present in our environment):

For its realization it is necessary to obtain a serum sample for the determination of IgM dengue antibodies (Umelisa dengue IgM plus). This blood sample should be taken on the sixth (6th) day after the onset of symptoms. The date of onset of fever (which is the most common of all symptoms and on which the surveillance system is based) is generally taken as a reference.1,2,16,23

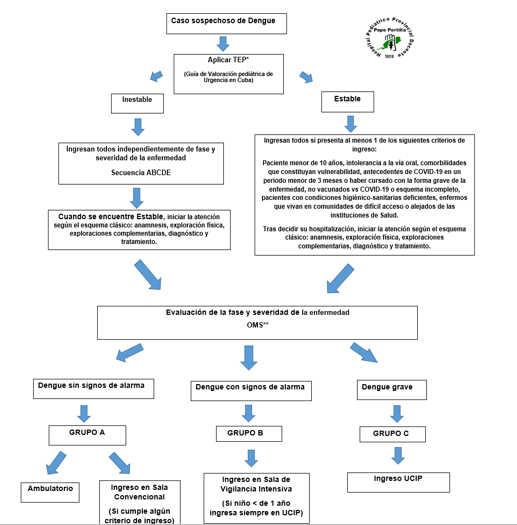

Initial pediatric emergency assessment of a patient with suspected dengue fever

It will be performed in any of the following settings in our hospital:

As expressed in the Guide for pediatric emergency assessment in Cuba, the first component of the sequence of assessments and actions is the general impression. This first phase or observational assessment should be performed using a highly efficient, prioritized and focused method called the pediatric assessment triangle (PET).

As its name suggests, the PET is composed of three sides: the patient's appearance, his respiratory work-up and his cutaneous circulation. With them, the PET does not provide us with a diagnosis of the patient, but it does provide us with an assessment of the physiological state and the patient's urgent needs to maintain adequate homeostasis.

The involvement of one or more sides of the triangle rules out a normal physiological state, and we are faced with a situation of unstable PTE (Table 2).26

Table 2 Integration of the pediatric evaluation triangle: general impression, physiologic status

| General aspect | Respiratory work | Circulation | Physiological status | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | N | Stable | |

| A | N | N | Unstable, CNS dysfunction, general | disorder TBI, pediatric stroke, hypoglycemia, exogenous |

| N | A | N | Unstable, respiratory distress | Asthma, bronchiolitis, CAP. |

| A | A | N | Unstable, respiratory failure | Asthma, low ARF (severe), lung trauma |

| N | N | A | Inestable, shock compensado | Unstable, compensated shock |

| A | N | A | Unstable, decompensated shock | Severe diarrhea, burns, penetrating wounds, dengue fever |

| A | A | A | Critical, cardiorespiratory failure. | PCR |

A: altered, N: normal, CTE: traumatic brain injury, CAP: community-acquired pneumonia, ARI: acute respiratory infections, CRA: cardiorespiratory arrest.

Steps for the care of the pediatric patient with suspected Dengue in CG after the initial emergency pediatric assessment.

Step no. 1: Complete anamnesis, thorough physical examination and laboratory tests.

Step 2: Clinical diagnosis, disease stage and classification according to severity.

From the information obtained in Step 1, the health care provider should be able to define the following criteria in the patient with suspected dengue fever:

Differential diagnosis

Table 3 presents the differential diagnosis to always take into account in each suspected case of Dengue, which also includes COVID-19.6,10

Table 3 Differential diagnosis of dengue fever

| Conditions that simulate the febrile phase of Dengue Fever | |

|---|---|

| Influenza-like syndrome: | influenza, measles, mononucleosis, seroconversion, COVID-19. |

| Diseases with exanthem: | rubella, measles, scarlet fever, meningococcal infection, drug allergy, COVID-19. |

| Acute diarrheal diseases: | Rotavirus, other enteric infections. |

| neurological manifestations: | Meningoencephalitis/febrile seizures. |

| Conditions that simulate the critical phase of Dengue fever | |

| Infectious: | acute gastroenteritis, malaria, leptospirosis, typhoid fever, viral hepatitis, acute HIV, bacterial sepsis, septic shock, COVID-19. |

| Neoplasms: | Acute leukemias and other neoplasms. |

| Other clinical conditions: | acute abdomen, acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, perforation of hollow viscera, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia and/or bleeding, thrombopathies, renal failure, respiratory distress, systemic lupus. |

Admission criteria

Step 3: Treatment for intervention groups A, B and C. 1,2,6,23

Group A. Dengue without alarm signs

Management in a conventional ward if the patient meets any admission criteria. Otherwise their management is outpatient.

Behavior:

Group B. Dengue with alarm signs

Admission to intensive surveillance ward.

Behavior:

Parenteral hydration schedule for Group B

Start hydration with crystalloid solution (Ringer Lactate or 0,9 % saline): 10 mL/kg to be given in one hour in the emergency department.

Re-evaluate. If there is clinical improvement and diuresis is ≥ 1 mL/kg/h, the patient is admitted with hourly monitoring until four hours after the end of the critical phase.

Intravenous fluids may be gradually reduced to 5-7 mL/kg/h for two to four hours with hourly patient monitoring.

Reassess the patient. If clinical improvement is evident and urine output is ≥ 1 mL/kg/h, the drip may be reduced to 3-5 mL/kg/h for two to four hours, always monitoring the patient hourly.

Re-evaluate the patient. If clinical improvement is evident and urine output is ≥ 1 mL/kg/h, reduce the drip to 2-4 mL/kg/h and continue for 24 to 48 hours.

It is necessary to provide the minimum of intravenous fluids to maintain at least a diuretic rate of 1 mL/kg/h.

Intravenous fluids are usually necessary for only 24 to 48 hours.

Clinical improvement is given by:

If after the administration of the first crystalloid solution load of 10 mL/kg, to pass in one hour, the patient is reevaluated and there is no clinical improvement, the patient should continue his management in the emergency department and repeat the second crystalloid solution load of 10 mL/kg, to pass in one hour).

If in a new reevaluation after that second load there is still no clinical improvement, then a third load of crystalloid solution of 10 mL/kg in one hour can be given.

If there is no clinical improvement, the patient should be carefully reassessed and reclassified as severe dengue with shock and managed as Group C and transferred to PICU.

Group C. Severe dengue

CONCLUSIONS

Dengue is a disease of systemic and dynamic behavior, which complicates the clinical-epidemiological scenario of the country and requires high scientific preparation for its confrontation. This protocol does not replace the one approved by the National Pediatric Group, but complements and summarizes a series of aspects that are essential for the management of the child with dengue.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Síntesis de evidencia: Directrices para el diagnóstico y el tratamiento del dengue, el chikunguña y el zika en la Región de las Américas. [Internet]. 2022 [citado el 07/01/2023]; 46: e82. Disponibl en: Disponibl en: https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2022.82 1. [ Links ]

2. Directrices para el diagnóstico clínico y el tratamiento del dengue, el chikunguña y el zika. Edición corregida [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2022 [citado el 07/01/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://femecog.org.mx/docs/9789275324875_spa.pdf 2. [ Links ]

3. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Epidemiological Update: Arbovirus [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2020 [citado el 07/01/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-update-dengue-and-other-arboviruses-10-june-2020 3. [ Links ]

4. Dehesa LE, Gutiérrez AAFA. Dengue: actualidades y características epidemiológicas en México. Rev Med UAS [Internet]. 2019 [citado el 07/01/2023]; 9(3): 159-170. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://dx.doi.org/10.28960/revmeduas.2007-8013.v9.n3.006 4. [ Links ]

5. Chediack V, Blanco M, Balasini C, et al. Dengue Grave. RATI [Internet]. 2021 [citado el 07/01/2023]; 38: e707.10102020. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revista.sati.org.ar/index.php/MI/article/view/707 5. [ Links ]

6. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Dengue y dengue grave [Internet]. Ginebra: OMS; 2020 [citado el 07/01/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue 6. [ Links ]

7. Kularatne SA, Dalugama C. Dengue infection: Global importance, immunopatho-logy and management. Clin Med (Lond) [Internet]. 2022 Jan [citado el 07/01/2023]; 22(1): 9-13. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35078789/ 7. [ Links ]

8. Tamayo Escobar OE, García Olivera TM, Victoria Escobar N, González Rubio YD, Castro Peraza O. La reemergencia del dengue: un gran desafío para el sistema sanitario latinoamericano y caribeño en pleno siglo XXI. Medisan [Internet]. 2019 Jan [citado el 07/01/2023]; 23(2): 308-324. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1029-30192019000200308 8. [ Links ]

9. Alonso LSN. Ofrece ministro de Salud Pública actualización sobre situación epidemiológica y programas priorizados [Internet]. Sitio oficial de gobierno del Ministerio de Salud Pública en Cuba; 2022 [citado el 31/12/2022]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://salud.msp.gob.cu/ofrece-ministro-de-salud-publica-actualizacion-sobre-situacion-epidemiologica-y-programas-priorizados/ 9. [ Links ]

10. Kliegman RM. Nelson Tratado de Pediatría [Internet]. 21ª Edición Booksmedicos; 2020 [citado el 10/09/2022]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://booksmedicos.org/nelson-tratado-de-pediatria-21a-edicion/ 10. [ Links ]

11. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Dengue: guías para la atención de enfermos en la Región de las Américas [Internet]. 2ª ed. Washington, DC: OPS; 2016 [citado el 10/09/2022]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/28232?locale-attribute=es 11. [ Links ]

12. Izquierdo A, Martínez E. Utilidad de la identificación de los signos de alarma en niños y adolescentes con dengue. Revista Cubana de Pediatría [Internet]. 2019 [citado el 07/01/2023]; 91(2): 1-13. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-75312019000200005 12. [ Links ]

13. Real J, et al. Caracterización clínica del dengue con signos de alarma y grave, en hospitales de Guayaquil. Revista científica INSPILIP [Internet]. 2017 [citado el 07/01/2023]; 1(1): 1-18. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2019/04/987761/29-caracterizacion-clinica-del-dengue-con-signos-de-alarma-y.pdf 13. [ Links ]

14. Consuegra Otero A, Martínez Torres E, González Rubio D, Castro Peraza M. Caracterización clínica y de laboratorio en pacientes pediátricos en la etapa crítica del dengue. Rev Cubana Pediatr [Internet]. 2019 Jun [citado 28/06/2023]; 91(2): e645. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-75312019000200003&lng=es 14. . [ Links ]

15. Saiful Safuan Md-Sani, Julina Md-Noor, Winn-Hui Han, et al. Prediction of mortality in severe dengue cases. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2018 [citado 28/06/2023]; 18(1): 232. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3141-6 15. [ Links ]

16. Kharwadkar S, Herath N. Clinical Symptoms and Complications of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya Infections in Pacific Island Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2022. Disponible en: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=415523816. [ Links ]

17. Wong JM, Adams LE, Durbin AP, Muñoz-Jordán JL, Poehling KA, Sánchez-González LM, et al. Dengue: A Growing Problem With New Interventions. Pediatrics [Internet]. June 2022 [citado 28/06/2023]; 149(6): e2021055522. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/149/6/e2021055522/187012/Dengue-A-Growing-Problem-With-New-Interventions 17. [ Links ]

18. Argentina. Ministerio de Salud. Enfermedades infecciosas: Dengue. Guía para el equipo de salud [Internet]. 4 ed. Buenos Aires: MSAL; 2016 [citado 28/06/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2018-10/0000000062cnt-guia-dengue-2016.pdf 18. [ Links ]

19. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Dengue: diagnóstico e manejo clínico: adulto e criança [Internet]. 5 Ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2016 [citado 28/06/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://portaldeboaspraticas.iff.fiocruz.br/biblioteca/dengue-diagnostico-e-manejo-clinico-adulto-e-crianca/ 19. [ Links ]

20. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. 2018 Red Book. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 31th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: Dengue; 2018 [citado 28/06/2023]: 317-319. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://publications.aap.org/aapbooks/book/546/Red-Book-2018-Report-of-the-Committee-on?autologincheck=redirected 20. [ Links ]

21. Pothapregada S, Sivapurapu V, Kamalakannan B, Thulasingham M. Validity and usefulness of revised WHO guidelines in children with dengue fever. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research [Internet]. 2018 [citado 28/06/2023]; 12(5): SC01-5. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.jcdr.net/ReadXMLFile.aspx?id=11528 21. [ Links ]

22. Paraguay. Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social. Dirección General de Vigilancia de la Salud. DENGUE: Guía de Manejo Clínico [Internet]. Asunción: OPS; 2012 [citado 28/06/2023]: 48p. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/canada/dmdocuments/Dengue_NUEVO2013_web.pdf 22. [ Links ]

23. Parmar, et al. Patterns of Gall Bladder Wall Thickening in Dengue Fever: A Mirror of the Severity of Disease Ultrasound Int Open [Internet]. 2017 Apr [citado 28/06/2023]; 3(2): E76-E81. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://eref.thieme.de/ejournals/2199-7152_2017_02?context=search#/0 23. [ Links ]

24. Oliveira RVB, Rios LTM, Branco MRFC, Braga Júnior LL, Nascimento JMS, Silva GF, et al. Valor da ultrassonografia em crianças com suspeita de febre hemorrágica do dengue: revisão da literatura. Radiol Bras [Internet]. 2010 [citado 28/06/2023]; 43(6): 401-407. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/j/rb/a/M9DLnL3p77qHCFB3qXD39gQ/?lang=pt 24. [ Links ]

25. Rojas Hernández JP, Bula SP, Cárdenas Hernández V, Pacheco R, Álzate Sánchez RA. Factores de riesgo asociados al ingreso a unidad de cuidados intensivos en pacientes pediátricos hospitalizados por dengue en Cali, Colombia. Rev CES Med [Internet]. 2020 [citado 28/06/2023]; 34(2): 93-102. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-87052020000200093 25. [ Links ]

26. Sánchez Cabrera YJ, López González LR, Marquez Batista N. Guía de valoración pediátrica de urgencias en Cuba. Revista Cubana de Pediatría [Internet]. 2022 [citado 28/06/2023]; 94(4): e2013. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revpediatria.sld.cu/index.php/ped/article/view/2013/0 26. [ Links ]

27. Gobierno de Guatemala. Ministro de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Guia para el manejo clínico del dengue, primero, segundo y tercer nivel de atención [Internet]. Guatemala; enero de 2022 [citado 28/06/2023]. Disponible en: http://epidemiologia.mspas.gob.gt/files/2022/dengue/27. [ Links ]

28. Lineamientos de dengue [Internet]. Secretaria de Salud Honduras; 2019. [citado 07/01/2023]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.salud.gob.hn/site/index.php/component/edocman/lineamientos-de-dengue-19-de-julio-2019 28. . [ Links ]

Received: January 01, 2023; Accepted: January 14, 2023

texto en

texto en