Introduction

Ideology was studied from the perspective of language by some scholars of the past, mainly in the twentieth century. For instance, Bart (2008), pointed to the connection between ideology and semiotics, while Eco (2006), claimed that ideology should be studied in combination with rhetoric. Derrida (2000), developed a deconstruction method similar to the method of deideologization, and Jameson (1981), examined the relationship between language and ideology through the prism of the “political unconscious”.

Talking about the discursive approach today, we would like to name the following researchers of ideology: Gavrilova (2010); Musikhin (2011). The relationship between political discourse and ideology was analyzed by Van Dijk (2006), while Langacker (1991) proposed shifting the focus from the word or sentence to discourse in the analysis of ideology. This research method was developed in the works of Bybee (2006). In this regard, we would also like to mention such Russian linguists as Golovanevsky (2017). Recently, with the advances in information technologies, the “Usage-Based Model” has undergone some changes and has eventually transformed into an approach based on corpus research.

The contribution of this paper to the literature is determined by the fact that the theoretical principles formulated in the article and the conclusions drawn have significantly developed the analysis of ideological concepts. Using linguistic and cognitive modeling, we described the aspect of the concept content that is expressed by linguistic means. Having analyzed the variants of the ideological concept, we determined the main conceptual areas marked with the described ideologeme. As a result, we identified and analyzed five main and four peripheral variants in the content of the concept “the Russian idea”. We analyzed the transformations of the intension of the ideologeme that were driven by socio-cultural and historical factors.

The ideologeme “The Russian Idea” is the core around which the dominant system of concepts is hierarchically built. These concepts represent the religious and philosophical worldview of the Russian thinkers living abroad in the first half of the twentieth century. The typology of the variant components of the concept “The Russian Idea” in the Russian linguistics can be represented through a concept-image, a concept-frame, and a concept prototype (Starodubets, 2005).

We would like to emphasize that in the Russian linguistic picture of the world, the specifics of the ideological conceptualization of the Russian idea can be determined with a cognitive-matrix analysis of conceptual areas necessary for the actualization of the meaning of the word, “none of which is strictly binding”, but our experience and knowledge predetermine its connection with this concept (Kulikov, 2008).

Another reason justifying the choice of this research method is the fact that ideologemes with the denotative component “Russian” rely on the presupposition “in comparison with an attribute that does not refer to Russian” (“They realized that we wanted something, something terrible and dangerous to them; they understood that there are many of us, ... that we know and understand all European ideas, and that they don’t know our Russian ideas, and if they do, they won’t understand them” (F. Dostoevsky “Writer’s Diary”, 1877) (Peskov, 2007, p. 64). It is of interest that according to S.P. Shevyrev, the Russian idea was understood as the idea “different from the German one” (Peskov, 2007, p. 64). This presupposition predetermines and launches the mechanism of cognitive comparison in the context of the “competitive dominant of the Russian culture” (Peskov, 2007, p. 72), which becomes “the trigger of the conceptualization process” (Kulikov, 2008, p. 80).

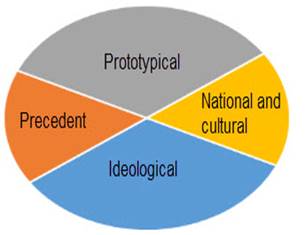

In our opinion, the cognitive matrix of the concept of the Russian idea, represented by the intension and the implication, has the following structure:

Precedent component.

Prototypic component.

Ideological and evaluative component.

National cultural component.

These components are the elements of the intension, the core part of the ideological concept. We define such linguistic units as the significant denotative ideologized composite names that “initially did not have any non-evaluative meaning, while the socio-ideological evaluative component of their content is inherent in both the denotatum and significatum, respectively”. (Starodubets, 1999, p. 36)

At present moment, Russian linguistics is actively exploring ideological concepts, ideological evaluations, and evaluativity. The well-known term “ideologeme” has become the key one in cognitive linguistics.

The theoretical aspects of the ideologeme have been explored in the fundamental works of Klushina (2014).

We share the opinion of Malysheva (2009), who defines the ideologeme as “a multi-level concept of a specific type, whose structure (in the core or on the periphery) actualizes ideologically marked conceptual features that embrace the collective, often stereotypical and even mythologized idea that native speakers have of power, state, nation, civil society, political and ideological institutions”. (p. 35)

Obviously, according to this position, there is no difference between the terms “ideologeme” and “ideological concept”.

In our opinion, the ideologemes containing composite names are currently very productive: the Russian world, the Russian idea, Russian weapons, the Russian soldier, Russian culture, the Russian character, the Russian national identity, Polite People, etc. We believe it is viable to carry out the linguistic-cognitive description of these ideologemes by analyzing the frame semantics (Boldyrev, 2008). A good example is the content analysis of the ideologemes “The Russian World” and “Polite People” performed by Timofeev, a post-graduate student of Ivan Petrovsky Bryansk State University under our scientific supervision (Timofeev, 2018).

As for the status of composite names, there is a broad understanding of phraseological units due to the concept of reproducibility. Thus, both phraseological units and composite names fall into the same category. In turn, the semantic concept is based on the criteria of integrity, imagery, and expressiveness, which underlie the status of a stable language unit. This means that composite names should not be included in the group of phraseological units of the language.

We support the semantic concept of phraseological units; therefore, we believe that composite names and phraseological units should be differentiated according to the functions they perform in the language. For composite names, like for words, the nominative function is the main one, while imagery and connotative meaning are the markers of phraseological units. Moreover, it is obvious that connotation cannot be a feature of the composite name. The connotative co-meaning in a composite name probably has a secondary function and does not in any way influence the categorical representation of the primary nominative meaning of the phrase.

The composite names are combinations of words that denote various phenomena of reality and represent an integration that has a semantic, structural, and grammatical unity that is equivalent to one word. They act as a general concept of a class of objects in the real world. They have the same structural and semantic features as variable phrases, and are similar to phraseological units in terms of their use. However, composite names are fixed phrases of a different kind. They are characterized by lexical divisibility of component words. Consequently, as far as their semantics is concerned, these linguistic units cannot be considered phraseological units.

The components of composite names act as markers of the differential features of the denotatum. Therefore, each of them carries a part of the aggregate meaning. The main specific feature of their semantics is the ability to decompose the general meaning into components. Stable lexical compatibility of the components enables the creation of a new meaning that encompasses the features of extra-linguistic reality. The meaning obtained as a result is an integral and qualitatively new unity that dominates over the meanings of its components and at the same time does not obscure the semantics of the components.

We support the position of Burov (1999), who attributes composite names to the area of nominative analytism (or the blending method of nomination.

In our opinion, the composite name THE RUSSIAN IDEA is a two-component formation that emerged by expanding the noun with the adjective. Its contextual blended content (philosophical, political, religious, and aesthetic) is the result of a secondary nomination, when the attribute marks the contextual “increment” of the content.

The modern linguistic methods of exploring ideology are based on the theories developed by individual researchers, as well as schools of thought that have their own approach to studying the issue. First of all, let us consider the basic theories of ideology.

Poststructuralists consider ideology through the prism of semiotic processes occurring in a language. In this regard we would like to mention the work of Bart (2008), who claims that semiotics (the science of meanings) is basically a science of ideologies. Bart analyzes the functioning of linguistic ideological mechanisms. According to him, ideology is a modern linguistic myth, a connotative system that assigns indirect meanings to objects.

Eco (2006), also worked in this field. The Italian scientist viewed ideology as “the uttermost connotation of the totality of connotations associated with both the sign itself and the context of its use”. Exploring the ideological processes of the language, Eco (2006), insisted that ideology should be studied in the immediate connection with rhetoric. Later, the concept of discourse, which is so significant in the modern linguistic research, began to play a more important role in the study of ideology.

French scientist Derrida (2000), developed a method of deconstruction, which can also be represented as a method of deideologization. The method allows identifying hidden oppositions in order to demonstrate the implicit advantages of one of them over another.

In the age of postmodern, studying language and ideology, one should determine the relationship between representation and narration. For instance, Baudrillard (2000), applied the idea of the linguistic pressure of ideology to consider the radicalization of the principle of arbitrary sign proposed by F. Saussure and the absence of reality behind the signs.

In his “Political Unconscious”, Jameson (1981), examined the relationship between language and ideology through the prism of the process bearing the same name as the book title. Jameson’s method aims to identify the ideological interpretive code, through which one can later carry out psychoanalytic, semiotic, and other types of research. In the framework of the linguistic approach, ideological language is viewed through the prism of discourse, and language is understood as a symbolic system used for propaganda and political communication. The study of language implies study and analysis of individual units that influence the recipient’s consciousness.

As mentioned above, modern methods of studying ideology from linguistic perspective rely on the accumulated experience of researchers in this area, mainly those from the twentieth century. Next, let us consider the key features and approaches to studying the problems relevant nowadays.

The greatest contribution to the study, analysis and systematization of the relationship between political discourse and ideology was made by Van Dijk (2006). According to him, ideologies are the core structures underlying social cognition which representatives of various groups, organizations, and institutions adhere to. To explore political ideology, Van Dijk proposes the following stages of context analysis: social, cognitive, and discourse analysis.

Among the diverse methodological approaches to the study of ideology, we would like to highlight the one developed by Oxford professor Freeden (1996), “Ideology and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach”. According to this concept, ideology is interpreted in terms of semiotics and takes into account both explicit and implicit meanings of the sign. The study of ideology focuses on analyzing the ideas expressed in the text. Thus, first one should analyze the signs that make up the language of a given ideology. The basic unit of ideology and, therefore, the main subject of analysis in the theoretical study of ideology is a political concept.

Another approach, “The Usage-Based Model,” was developed by Langacker (1991), in the early 1990s. Firstly, this theory shifts the emphasis from a word or a sentence to a text (the discourse), which means that one does not analyze individual units, but the context as a whole. Secondly, the researcher relies on the quantitative component of the language, i.e., focuses on the analysis of more frequent units, rather than study each one separately. Such an approach is actively applied by Bybee (2006), and her followers. This view is supported by other researchers, for example, Greenberg (2005), in his theory of marking. Thirdly, various research methods (for example, psycholinguistic, semiotic, and sociolinguistic) are incorporated in the analysis, which confirms the flexibility in choosing tools for analyzing the meaning.

We should note that modern corpus has certain specifics that distinguish it from other approaches. This is an intentional focus on other genres, not only fiction, which determines the selection of texts for the corpus. This is extremely useful for researchers who seek to get a true picture of what is happening in the field they are exploring.

Materials and methods

The leading method in this study was the method of cognitive-matrix analysis of knowledge representation.

Arnold (1966), considered the concept of a matrix in the structural analysis of polysemants. Lanecker used this term “to describe a complex of hierarchically related conceptual areas which at the same time are associated with a particular concept” (Boldyrev, 2009, p. 48). Here, the researcher understands it similarly to the concept of “frame”. Boldyrev (2009), believes that “both I.V. Arnold and R. Lanecker apply this term to denote a network of structural and semantic variants of a polysemic or conceptual areas that underlie their formation and understanding”. (p. 48)

In cognitive linguistics, the matrix “is a special format of knowledge, the specifics of which imply combining various aspects of non-linguistic and linguistic knowledge within a single conceptual structure”. (Boldyrev, 2007)

In his “Conceptual Basis of the Language”, Boldyrev (2009), considers in detail the formation specifics of the matrix format of knowledge. He emphasizes that it is multidimensional, integrative, and non-stereotypical. Representation of this type of knowledge does not imply a hierarchical combination of conceptual areas (unlike the frame), and he determines the variants of their combinations in the structure of the matrix concept.

Thus, the cognitive matrix is “a system of interconnected cognitive contexts or areas of object conceptualization” (Boldyrev & Alpatov, 2008, p. 5), and “in the structure of the cognitive matrix, these cognitive contexts acquire the status of autonomous, independent from each other components” (Boldyrev, 2009, p. 490).

Cognitive-matrix analysis was first applied by Boldyrev & Kulikov (2006), to study the structure of dialect knowledge and the cultural specifics of language.

We consider it viable to describe the structure of the ideological concept THE RUSSIAN IDEA with the cognitive-matrix analysis of knowledge representation, given that it is undoubtedly a “natural development of... methods that are widely recognized in traditional linguistics (comparative method, analysis of dictionary definitions, and contextual analysis), as well as the methods of cognitive linguistics: conceptual, frame, and prototypical analysis, as well as cognitive modeling”. (Kulikov, 2008, p. 79)

According to the differentiation of cognitive matrices into general and specific ones proposed by Boldyrev, we established that the ideologeme THE RUSSIAN IDEA refers to a cognitive matrix of a specific type, which represents multidimensional knowledge as the core (“The Idea of Russia”) and the periphery (“matrix cells”), while the latter represents the core in different cognitive contexts.

In addition, in the research, we applied complex theoretical, linguistic ideological, comparative, interpretative, component, and contextual analyses.

Results and discussion

The considered variants of the ideological concept РУССКАЯ ИДЕЯ (THE RUSSIAN IDEA) mark the following basic conceptual areas (the differences are shown with letter case and quotation marks):

Русская Идея is the personification of the Divine as the fact of the great mission of Russia and its intellectuals. “Русская идея” is an appositive of a name that is conceptualized in the context. Русская идея is the manifestation of the essence of Russian and Slavic civilization, the Russian way of life, the Russian character, and the true mission of the Orthodox Russian people, S/spirituality, the aesthetic and moral component of the Russian culture and Russian Messianism (nobility, exceptional and spiritual nature, the deep meaning of creativity, purification, sacrifice, etc.); русская идея is an ideological focus, a marker of the ideology implying the co-existence of the nation and the state, S/sobornost (the spiritual community of many jointly living people) as an integration of heavenly and earthly experience in the Russian community; “русская идея” as the primary terminological definition of the concept.

In a generalized form, the content of the ideological concept (ideologeme) THE RUSSIAN IDEA at the intension level is represented by isomorphic conceptual areas (in this case, the core invariant area is “The Idea of Russia” represented by matrix cells):

Scientific or public theory of the successful development and revival of the people (“The Third Rome”, “Slavophilism”, “socialism”, and “communism”);

The phenomenon of national Spiritual/spiritual co-existence, co-knowledge, and self-awareness;

Devotion to “Holy Russia” representing God’s plan for Russia and religious Messianism;

“The core of the recreated social and state ideology of great Russia”.

National/national idea as the embodiment of a Russian national identity and the Russian national character.

The idea of Sobornost/sobornost.

The idea of heart/Heart, love/Love, conscience/Conscience.

As already noted, the cognitive matrix of the concept “the Russian idea” has the following structure:

A precedent component. We should note that until the emergence of this term in the nineteenth century (in the works of F.M. Dostoevsky), the concept THE RUSSIAN IDEA existed in a latent, inexplicit form as an image. In this regard, the chronological origin of the concept is “The Epistle on Evil Days and Hours” by elder Philotheus with his well-known formula “Moscow is the Third Rome”.

The prototypic component (from F.M. Dostoevsky to its most active manifestation in the works of Russian religious philosophers in the first half of the twentieth century). It is defined by the concepts of FREEDOM, LOVE, HEART (according to I.A. Ilyin), SOBORNOST (as interpreted by the Slavophiles A.S. Khomyakov, N. Lossky, V.V. Rozanov, and N.A. Berdyaev), ALL-UNITY (Vl. Solovyov), RUSSIAN LITERATURE (according to S.P. Shevyrev: “Ancient Russian literature presented the Divine principle through “the Christian feeling” of the Russian people. The Russian Church was the backbone of the Russian state when monarchy was created”; “the national literature in its brightest manifestation is “the expression of the national spirit in the word, the educated and complete expression”; “the history of Russian literature transforms into Russian philosophy” (Peskov, 2007, p. 59, 69). “The Russian idea becomes a criterion for evaluating literature; a critic uses it as a basis to determine the extent to which modern literature embodies the national identity” (Peskov, 2007, p. 64). In addition, in the paper “The Russian idea as the basic concept of the religious philosophy of the Russians living abroad in the first half of the twentieth century” we described frame slots representing situational models: “rejection of the death penalty”, “Russian Messianism”, “compassion”, “search for the Kingdom of God,” “narodnik movement,” “The Tolstoyan movement,” “the idea of brotherhood,” “eschatology,” “anarchism,” and “Divine Humanity” (Starodubets, 2005, p. 43).

Ideological and evaluative component. It is implemented with situational models of the invariant type such as “national”, “state”, “S/spiritual”, “Orthodox”, “S/sobornost” (see more about the situational models of the frame and the analysis of the explication of the concept THE RUSSIAN IDEA in the work bearing the same title written by Russian religious philosopher N.A. Berdyaev (Starodubets, 2005). This component is also determined by the ambivalent evaluation of the ideologeme which is expressed through contextual definition (the new Russian idea: “What is good for business is good for Russia”, “beat your own people, others will be afraid of you”, “Pugachev’s rebellion”, “the emotions of bashing”, “nationalist anti-Semitism”, “Russian fascism”, “traditional burping and producing large heaps of digested products”).

National and cultural component (from the second half of the twentieth century to the present day) is represented with the attribute Russian, which is a mythological ethnocultural archetype that refers the recipient to the paradigm of values formed in Russian culture, namely: the Russian world, the Russian character, the “Russian spirit” (a fixed phrase), the Russian soul, the Russian person, the Russian soldier, the Russian people, the Russian winter. I.A. Ilyin also spoke about “Russian conscience”, “Russian heart”, “Russian family”, and “Russian faith”. We believe that the attribute Russian is hypersemantized (“the functor-attribute”). It concentrates (absorbs) syntagmatic and paradigmatic micro- and macrocontextual functions, and explicates the evaluation and connotation “spirituality” in the discourse (Starodubets, 2017). Accordingly, there is the attribute Russian ↔ national, Russian ↔ spiritual, and “semantic contamination” of the attributes.

In turn, “the implicative potential of the concept is formed as a structured probabilistic set of attributes implicatively associated with the intensional core of the concept” (Boldyrev, 2004, p. 59). This potential is realized by the peripheral part of the matrix and is represented by a wide range of associates. The implication includes such element as an identification component represented by the personification of people, symbols, and anti-symbols, such as “fevronka”, “Zatulin”, “Svistunov”, etc. (“Who knows, maybe over time Andrei’s dream will come true and fevronka will become part of the national Russian idea, becoming more popular than a Valentine card that came to us from the West” (Postnova, 2011).

Another element is the associative component represented by a set of conceptual metaphors realized through the compatibility of the composite name the Russian idea and defining the key representant of the concept (“the idea of the heart”, “contemplating love”, “divine historical conception”, “children reading Pushkin”, “vodka is, of course, not a Russian idea, but is rather close to it”, etc.). It should be borne in mind that there are implicit associates, the explication of which is due to the decoding of cognitive metaphors. For example, “Tymoshenko saddles the Russian idea” (the Russian idea is compared to “a horse or a donkey that can be saddled”), “Bears privatize the Russian idea” (the Russian idea is the object of privatization), “to interbreed the Russian idea with communism” (the Russian idea is a biological object for interbreeding with somebody or something).

The named conceptual components are the variants of the macro-position “Idea of Russia” (Pavel Florensky): “However, I believe and hope that, having exhausted itself, nihilism will prove its worthlessness, and then, after the collapse of all this abomination, heart and mind… will turn to the Russian idea, the idea of Russia” (Konovalov, 2007) (Fig.1).

Let us turn to the Russian National Corpus (2003). The search query revealed 140 documents with the composite name the Russian idea in the main corpus and 68 in the newspapers section. Let us analyze the expression of a composite name based on the contexts selected from the RNC and the content of an attributive composite name from the perspective of the syntagmatics of the microcontext.

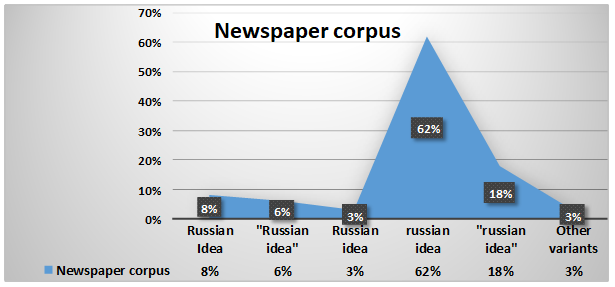

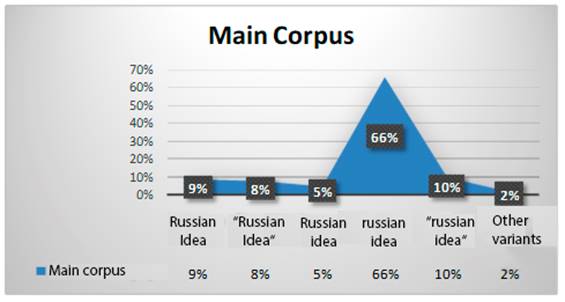

In the contexts presented in the RNC, there are five most frequent variants of the analyzed composite name (the differences are shown with letter case and quotation marks, see Figures 2 and 3).

Variant 1 Русская Идея

In the main Russian National Corpus, the composite name Русская Идея is used in 9% of the total number of contexts, and in the newspaper section - in 8%.

The main corpus:

“I see the salvation of the Russian Idea (Русская Идея) (and Russian culture as a whole) in the fact that it has always been on the path of discovering the laws of nature and the laws of co-living” (Burkov, 1990).

The newspaper corpus: “Maybe, he still does not know what the Great National Russian Idea is about” (Gamov, 2001).

The use of two uppercase letters in the writing of the composite name determines its special symbolic meaning - the personification of the Divine, the Light as a fact of the great mission of Russia and its intellectuals (“Sometimes these bright minds do not even realize that they are led by the Russian Idea”, “To bring down the light of the Russian Idea, it was necessary to exterminate the best Russian intellectuals” (Burkov, 1990).

Variant 2: “Русская идея”

In the main Russian National Corpus, “Русская идея” is used in 8% of the total number of contexts, and in the newspaper section - in 6%.

1. The main corpus:

“The book of the former President of Finland, Mauno Koivisto “Русская идея”, a course on Russian history from Varangians to Putin on 241 page was presented in Moscow”. (Novosty, 2002);

Newspaper corpus:

“Monograph “Русская идея” by Shukshin (1999), Sigov (2007); “Русская идея” is used as a name of books, series of books, and television programs.

Variant 3: Русская идея

It was found in 5% of the cases in the main corpus, in the newspaper corpus - in 3%.

1. The main corpus:

- “The Russian idea generated by the Orthodox consciousness was consistently absorbing the spiritual qualities of the nation, at the same time expressing its “special physiognomy”, as Pushkin said ... we could consider “The Snow Maiden” the Russian idea expressed in the language of fine arts” (Petrova &. Vasnetsov, 2004).

- “In the detailed presentation of the content of the Russian idea, it manifests itself as an expression of the essence of Russian (Russian-Slavic) civilization, the Russian way of life, which ... perceived industriousness, mutual assistance, collectivism within the community and work team as a virtue, and at the same time asceticism, adventurousness, entrepreneurial spirit, initiative, admiration for courage and daring, high moral and ethical principles of honesty and decency” (“The Relevance of Russian Ethnopolitology”. The Life of Nationalities, November 23, 2001).

- “The Kingdom of Opona and the Russian Dream, Belovodye and Holy Russia, All Truth and Communism, the Russian idea and Spirituality are the faces of the proper” (N.L. Zakharov, “The System of Regulators of Social Action of Russian Government Officials (Theoretical and Sociological Analysis)”, 2002).

2. Newspaper corpus:

- “Does the Russian idea exist? ... The Russian idea for me is imagination, understanding harmony and beauty, aesthetic and moral perception of the world. ... The Russian idea is children who do not sniff glue in the basement, but read Pushkin in schools. ... The Russian idea refers to reasonable people, not to erect-walking people, cutting down a pine that bothers them and spitting in a stream. ... The Russian idea is the Noah man, not the Flood man” (Komsomolskaya Pravda & Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 2005).

The Russian idea is a marker of the ontological mission of the Russian-Slavic civilization in society and culture.

Variant 4: русская идея

This is the most common usage of this composite name. In the main corpus, it was found in 66%, in the newspaper corpus - in 62% of the cases.

1. The main corpus:

- “The Russian idea is a theoretical and spiritual doctrine that ensures the independence of the Holy Russia, the revival of the country, its transformation primarily into the independent nation, and it is the core of the recreated social and state ideology of great Russia, self-awareness of the nation, a meaningful desire of the people to establish a national state, better reality, improving their civilization and the way of life”. (“The Russian idea: National and all-Russian”, The Life of Nationalities, June 5, 2002).

- “The Russian idea was formulated as the idea of Sobornost” (Kireev, 2003).

- “Therefore, the Russian idea is in many ways a phenomenon of religious consciousness” (“Russian idea: National and all-Russian”, The Life of Nationalities, June 5, 2002).

One should note that the position of the composite name at the beginning of the statement involves the fusion of two ways of expression - русская идея and Русская идея: “The Russian idea today is the realization by Russians, the nation as a whole, of their identity, a common path, common tasks, common responsibility and obligation to build a better, more humane and fairer society” (“On the advantages of the national idea and attempts to define it”, The Life of Nationalities, June 16, 2004).

Newspaper corpus.

- “One can find many definitions of it in Berdyaev’s texts, but most of them are presented in as an objection: the Russian idea is not bourgeois, not nationalistic, not Western or Eastern, not like the Germanic or German idea, and other negations and dichotomies that he loved so much” (Vanchugov, 2014).

- “Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky wrote that the Russian idea is all-humanity and perception of the entire culture of the world” (Lapteva, 2007).

- “The whole Russian idea reduced itself to the traditional burping and producing large heaps of the products of digestion” (Lebedev, 2003).

The variant русская идея as “the core of the social and state ideology of great Russia” marks the religious understanding of state life through higher forms of experience (“religious experience, moral experience, aesthetic experience, perception of someone else’s spiritual life, and intellectual intuition” (Vorobyov, 2008), and Sobornost/sobornost.

Variant 5: “русская идея”

In the main corpus, this usage was registered in 10% of the cases, in the newspaper corpus - in 18%.

1. The main corpus.

- “For the first time, the very term “the Russian idea” was used in the 70s of the nineteenth century by our great thinker F.M. Dostoevsky” (“The Russian idea: national and all-Russian”, The Life of Nationalities, June 5, 2002);

- “Russia also balances between “Westernism” and the “The Russian idea”, eventually creating its own model of society” (Dorfman, 2003).

Newspaper corpus.

“This is “the Russian idea” as Berdyaev understands it: to overcome bourgeois ideology, but not to end up with socialism or communism” (Vanchugov, 2014).

In the newspaper corpus, this variant was used in the meaning “promising direction of a party politics”: “A party with “the Russian idea” will be able to receive up to 10% of the votes in 2016, experts predict” (Sivkova, 2013).

The given variant of the composite name presentation is a marker for expressing the primary conceptual content of a terminological nature. It is used in such contexts as: “to refer to the concept of “the Russian idea”, “books about “the Russian idea”, “an essay about “the Russian idea”, etc.

There are few cases of РУССКАЯ ИДЕЯ, РУССКАЯ идея, “русская” идея, русская “идея” (2% in the main corpus and 3% in the newspaper corpus).

Capitalization of the given composite names assumes the dominance of the acting function and was identified in the newspaper corpus. The quotation marks in the first or the second word suggest a critical or ironic connotation: “Some of your collections were based on a space theme, some - on other “Russian” ideas popular in the West” (Medovnikova, 2012); “Slavophiles, in fact, bowed down more to the Russian “idea” than to fact or power” (Berdyaev, 1915).

Fig. 2 Variants of the expression of the composite name “the Russian idea” in the main section of the Russian National Corpus.

Conclusion

As we can see, THE RUSSIAN IDEA is not just an idea (like in the advert “The Russian radio is not just radio”), but this concept implies the appeal of the addresser and the addressee to a complex conceptual area, a configuration of meanings connected with historical, socio-cultural, ideological, and spiritual phenomena and knowledge.

Cognitive linguistic modeling of the concept allowed us to describe the part of the concept that is expressed linguistically. The ideological concept THE RUSSIAN IDEA includes five main and four peripheral variants.

In addition to this, there are variations in the presentations of these matrix components. For example, V.V. Vorobyov includes the following components in the paradigm of the religious nature of the Russian idea: “religion of the people, Christianity, the absolute value of the individual, Orthodoxy, Orthodox Christianity, sobornost, Russian nation, religious messianism, spiritual integrity, people chosen by God and bearers of religious mission, religious emancipation of personality, Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality”. (Vorobyov, 2008, p. 152)

The periphery of the ideological concept THE RUSSIAN IDEA is represented by the interpretation field or the implication (“the associative aura of the concept”), “faces/symbols (anti-symbols) embodying the Russian idea in its original or transformed form”: ambivalent symbols of the Russian prototypical idea (“The Kingdom of Opona”, “The Snow Maiden”, “Holy Russia”) and of a subjective-author’s nature (“Noah’s man”, “children reading Pushkin”, “Fevronka”), or subjective-author’s anti-symbols (“not an American dream”, “not the Flood man”, Zatulin, and Svistunov).

It should also be noted that the composite name the Russian idea in modern Russian language is an ideologized combination, a stable verbal complex expressing ideological evaluation and ethnocultural connotation. The ideological significance of the composite name the Russian idea is the result of hyper-semantization of the attribute Russian in the Russian linguistic picture of the world. Under this influence the non-evaluative intention of the language signs of the composite name “the Russian idea” is transformed into an invariant evaluative one, which can be realized in meliorative and pejorative variants. This transformation of the intention is determined by socio-cultural and historical factors and the conceptual picture of the world of Russian native speakers.