Introduction

In this study, we focus our analyses on the central question of economic resilience and smart specialization strategy. Examining the dynamics of a country’s innovation and economic growth dynamics, the authors like Frenken, et al. [1], point out that the diversity of sectors in different regions is important and the strength of the links between the elements of that diversity. Organizations compete by expanding their knowledge areas and ability to use more components of the knowledge space and industrial production.

This means that diversification promotes the diversity of innovative activities and the creation of new radical innovations through cooperation between different sectors of the economy. This kind of aspect is highly relevant to the Cuban economy and society. The ongoing global digitalization and globalization open up new opportunities to identify the strengths and priorities of economic and scientific-technological development in countries and regions. Nowadays, this is done through research on smart specialization strategies (S3). Also, the sustainability of smart specialization strategies is gaining more attention nowadays (S4), especially in the European Union.

One such direction is determining the level of specialization of the country’s economic sectors, i.e., industry [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. In essence, they are inseparable from analyzing the industry's structure. These methodologies have always been given significant attention in the scientific literature [7, 8, 9]. This fact was caused by the changing situation in trade relations ‒ changes in the degree of concentration of economic operators and states, the conditions of entering global markets, growth in the range of production, change in the degree of integration and diversification of enterprises, and also, finally in export and import strategies [10, 11, 12, 13].

Methodology of the study shortly

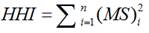

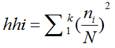

Being a commonly accepted measurement of market concentration, the HHI measures the ratio of firm size to the industry size as a proxy for the degree of competition among them (Herfindahl 1950, Hirschman 1964, Adams 2017). As noted above, the HHI index is defined as the total squared market shares of all firms within the industries at stake. The result of this exercise may range from 0.0 to 1.0, thus spanning a continuum ranging from the prevalence of a considerable number of tiny firms to a situation defined by only a monopolistic firm. HHI increases are typically understood as indicators of decreases in competition and increases in market power [14, 15, 16, 17]. One key advantage of the HHI vis-à-vis the C.R is that the former gives more weight to larger firms as it accounts for relative firm size distributions in each market. In fact, the former’s calculation differs from the latter’s insofar as an equation (1), for determining the HHI is as follows [18]:

Full background reviews of HHI analyses can be found in [19]. Data is collected fromthe OEC database (https://oec.world/en/profile/country/cub). Again, we find that the HHI is calculated by squaring each firm's market share and then totaling up the resulting numbers. The original reason why Lauraéus and Kaivo-oja [20], started their further development of the HHI is that this indicator does not account for size differences among the analyzed categories. At the same time, the authors concluded there to be good reasons for avoiding such potential calculational biases. The so-called S3 methodology includes many special methods and planning tools. Comparative advantage, resilience level, and innovation potential are typically measured [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28].

The new methodology for export and import portfolio analysis: Expanding the HHI toward the LKI

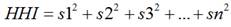

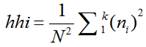

In the HHI, the Lauraéus-Kaivo-oja Index (LKI) is based on the subsequently outlined reasoning. First, Lauraéus and Kaivo-oja [19], support the argument shown in equation (2):

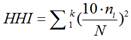

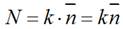

Which can be written using the mathematic equation (3):

Where by The sample size is = N, The count of different categories in the sample = k, and The average value of the sample classes =  .

.

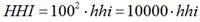

Yet, there is a way to remove the “1002”-part of the equation, as we can replace percentages with the decimals of 0.01-0.99, corresponding to 1-99%. Thus, we also avoid calculational problems related to values 0-10000, which are less intuitive than percentage values. Thus, we may create the index hhi, which means the HHI index (see equation (4)), without 1002.

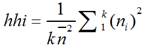

As we take out the 1002 out of the equation, have replaced the HII with the “hhi”, whose equation (5) is:

Which is equal (see equation (6)) to:

Yet, as the total quantity of the sample is = N, which is equal to the number of different classes in the sample, the total sum in the sample classes may be expressed as follows (equation (7)):

Consequently, we may argue that if the “hhi” may be expressed as shown in equation (8):

Then it may also be represented as equation (9):

Whereby  refers to 1 over k numbers of categories within the sample. Yet, the issue is that this

refers to 1 over k numbers of categories within the sample. Yet, the issue is that this  might generate a distorted analysis of key trends as if one has different numbers of categories in one’s sample, then one is incapable of comparing these categories with one another, for otherwise, it will distort the analysis [20]. Take the example of a sample consisting of 34 categories of goods

might generate a distorted analysis of key trends as if one has different numbers of categories in one’s sample, then one is incapable of comparing these categories with one another, for otherwise, it will distort the analysis [20]. Take the example of a sample consisting of 34 categories of goods  and 11 categories of services

and 11 categories of services  .

.

In this case, the fewer the classes, the bigger the percentage added to the “hhi” index. Thus, why such percentages should be added to an index arises. If all numbers of the samples are in one class, then  . Thus, one may safely remove

. Thus, one may safely remove  and retain a more informative and pertinent trend curve [20].

and retain a more informative and pertinent trend curve [20].

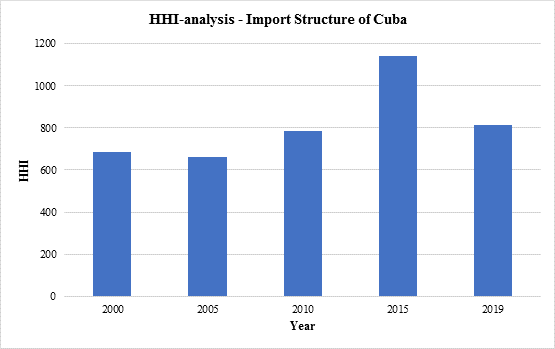

The Lauraéus-Kaivo-oja Index (LKI)can be represented with the equation (10):

If the maximal diaconal standard deviation is correctly expressed as  , then the divisor must be (k-1).

, then the divisor must be (k-1).

Thus,  appears to be the wrong divider, whereas the right one seems to be (k-1) n2.

appears to be the wrong divider, whereas the right one seems to be (k-1) n2.

Thus, the new novel LKI indicator must be as shown in the equation (11):

The LKI index is the square of standard deviation over the completely divided square of standard deviation (see [20]). The next section reports key results based on the HHI and the novel LKI indicators.

Results of HHI and LKI analyses

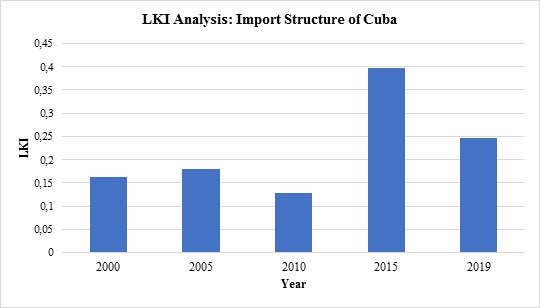

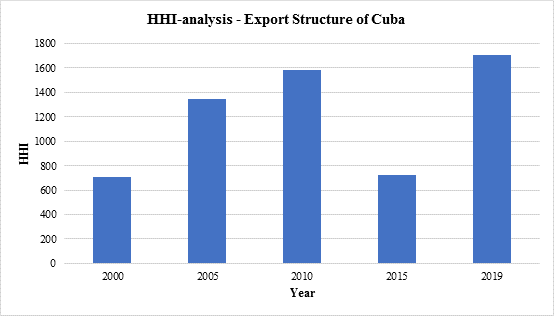

In this section, we report some key findings of our analysis. We have performed data analyses of export and import in Lithuania. First, we report the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index analysis of the Lithuanian export and import data. This analysis is based on the OEC database (https://oec.world/en/profile/country/cub). The Data pool covers 24 countries’ export and import data of the Cuban economy. It gives a robust picture of recent economic activities in the Cuban economy. In figure 1, we can observe trends in the structure of the export portfolio, and in figure 2, we see the import portfolio.

Fig. 1 Herfindahl-Hirschman Analysis of the Export Structure of Cuba. Years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019

We can observe that the Cuban export portfolio was not diversifiedin 2000-2010, but in 2015 itdiversified, but again concentration trend continued.

Fig. 2 Herfindahl-Hirschman Analysis of the Import Structure of Cuba. Years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019

We can observe that after 2005 concentration trend of Cuban import activities continued till 2015, but 2019 slightly became more diversified in 2019. Further more, we can note that based on HHI analyses, the export portfolio of the Cuban economy is more concentrated than the import portfolio of the Cuban economy.

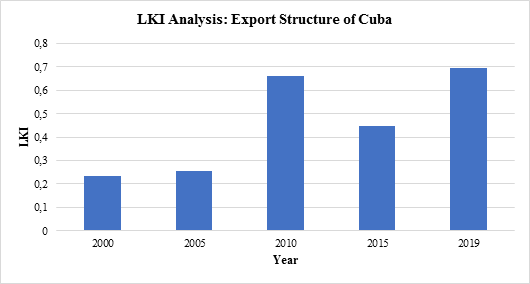

In figure 3, we report the results of the LKI analysis of the Cuban economy. This index-based analys is reveals that after 2005, the concentration of export structures increased considerably in the Cuban trade. However, in 2019, the concentration trend decreased slightly, almost at the same level as in 2010.

Fig. 3 Lauraéus- Kaivo-ojaAnalysis of the Export Structure of Cuba. Years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019

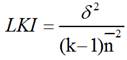

In figure 4, we report the results of the LKI analysis of the Cuban economy. We can observe that after 2005 low concentration trend of Cuban import activities continued till the year 2010, but in 2015 it changed slightly to become more concentrated but dropped to a lower level.

We can note thatbased on LKI analyses, the export portfolio of the Cuban economy is more concentrated than the import portfolio of the Cuban economy. The results are similar to HHI analyses.

In general, based onempirical analyses, we can note that resilience challenges of trade are more challenging in the field of export than import. This indicated that economic dependency problems are linked more to export than import activities.

Conclusions

This empirical study provides results of export and import structures of the Cuban economy and trade. Results are based on Herfindahl-Hirschman (HHI) and Lauraéus-Kaivo-oja (LKI) analyses. These results give knowledge-based background for the Cuban economy's export and import strategies. Especially these kinds of analyses give a sound knowledge base for smart specialization strategies of the Cuban economy. Results indicate that export-led strategies need some re-assessment from the resilience perspective of the Cuban export strategy. A more diversified export portfolio would be a smarter solution than the current concentration rate of the export portfolio. There is less need for re-assessment in the import strategy field because Cuba's import portfolio is already very diversified.