Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo

versión On-line ISSN 2310-340X

Coodes vol.12 no.1 Pinar del Río ene.-abr. 2024 Epub 30-Abr-2024

Original article

Savings and Credit Cooperatives and financial inclusion

1 Universidad Politécnica Salesiana. Ecuador.

2 Investigador independiente. Ecuador.

The article aimed to characterize the situation of financial inclusion in the rural sector of the Guayaquil canton, as well as the role of savings and credit cooperatives in this process. The hypothetical-deductive methods were applied, as well as the documentary review and analysis, the survey and the interview. The study was carried out in the rural parishes of Posorja, Puná, Tenguel and Morro in Guayaquil, Ecuador, where a total of 27,017 people over 18 years of age reside. It was obtained that savings and credit cooperatives have greater relevance in places where rurality and poverty are greater and that people in rural areas maintain a regular perception of the development of formal financial entities, since they are distrustful and dissatisfied with the way these establishments operate. Levels of financial inclusion are insufficient, while savings and credit cooperatives can contribute to improving this situation.

Key words: savings and credit cooperatives; financial inclusion; rural sector

Introduction

Financial inclusion is an issue of clear importance due to its relationship with economic and social development and the reduction of inequalities. So, it receives close attention from international organizations, government agencies, the academic field and also in the design and management of public policy by governments. Currently, thanks to technology and internet access, it has been increasing, which is positive since it contributes to the reduction of poverty, inequality and inequity (Rosado et al., 2020).

Despite these benefits that financial inclusion generates, only 50% of the adult population in the world has an account in a formal financial establishment; on the other hand, in Latin America and the Caribbean its use is lower, only reaching 39% and of this percentage only 8% of adults make loans in the formal financial sector (World Bank, 2018). This generates greater vulnerability for the population that does not have access to the formal financial sector.

In Ecuador, cooperatives, both financial and non-financial, have become the engine of the popular and solidarity economy. Savings and credit cooperatives (CAC in Spanish) can generate an important contribution to financial inclusion, due to their territorial proximity to different populations and their offer of more affordable financial services for different groups of the population. This is more significant in the rural sector.

It is important to recognize how necessary it is for rural areas of the country to achieve comprehensive development based on adequate financial access for its population. Hence, CACs have a vital role in this issue, as their popular and supportive principles differ from the marked agenda of formal banking institutions, which can generate a favorable context for individuals who reside in rural areas and the system in its set.

The objective of the article is to characterize the situation of financial inclusion in the rural sector of the Guayaquil canton, as well as the role of savings and credit cooperatives in this process.

The concept of financial inclusion is still under construction and there is no single definition of it. Below, some of the most important criteria provided by both specialized institutions and researchers are reviewed.

The World Bank (2022) defines it as the "access that people and companies have to various useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs-transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance that are provided in a responsible and sustainable manner". As evidenced, the World Bank focuses specifically on the conditions of access to financial products and services. For its part, the National Banking and Securities Commission (2020) defines it as "the access and use of formal financial services under appropriate regulation that guarantees protection schemes for users and promotes financial education to improve the financial capacity of all segments of the population". In this second definition, the dimensions are expanded by incorporating access, also use, protection and, very importantly, financial education.

Another institution like the Central Bank of Ecuador (BCE, 2021) refers to financial inclusion as: Access and use of quality financial services by individuals and companies capable of making informed choices. Financial products and services must be offered in a transparent, responsible and sustainable manner and must respond to the needs of the population.

For the BCE (2012), a series of conditions must be met to be able to speak of financial inclusion. These include basic financial knowledge, a conducive regulatory environment, adequate consumer protection, an adequate product offering and coverage of the financial sector.

For its part, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean has a distinctive position on financial inclusion, understanding it as more related to the productive aspect, both of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and households. Thus, Pérez Caldentey and Titelman Kardonsky (2018) in a document prepared for the aforementioned institution indicate that:

Financial inclusion encompasses all public and private initiatives, both from a demand and supply perspective, to provide services to households and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which have traditionally been excluded from formal financial services, through the use of products and services that suit their needs. Beyond expanding the levels of financial access and banking use, financial inclusion also refers to policies aimed at improving and perfecting the use of the financial system for SMEs and households that are already part of the formal financial circuit.

It is important to highlight the approach of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean by stating that financial inclusion has determining factors from both the demand and supply sides of financial products and services, which should be a topic on the agenda, both the public and private sectors, which concerns both families and individuals as well as small businesses, and that financial inclusion must actually impact their productive and economic capacities in general.

Raccanello and Herrera Guzmán (2014) consider that financial inclusion can contribute to the well-being of the population, by shifting income and consumption flows over time through savings and credit, as well as the accumulation of assets and the creation of a old age fund.

For Sierra Lara et al. (2024), factors such as financial crises, family over-indebtedness, insufficient savings levels, the growth of economic and social inequalities of all kinds, are issues that demand the promotion of financial inclusion.

The BCE (2021) outlines an important series of positive impacts that can be expected from financial inclusion, reinforcing its importance. Among them is the fact that it is an effective tool in the fight against poverty and inequality, which allows the empowerment of women, the realization of productive investments, and the increase in consumption and income. It also makes it possible to reduce transaction costs, as well as meet the needs of MSMEs. At the same time, it contributes to reducing financial market imperfections.

In any case, financial inclusion is essential to achieve a modification in the social and productive structure of the country. Meanwhile, it offers a range of possibilities to economic agents so that they can see their capabilities exploited.

Precisely, given that the Ecuadorian state recognizes the critical importance of financial inclusion for the economic and social development of the country, a National Financial Inclusion Strategy has been designed by the Central Bank for the period 2020-2024. This strategy has set four fundamental goals: a) A significant increase in access to financial services, measured through access to bank accounts; b) The expansion of the financial system's service points, mainly through correspondent agents; c) Increased use of digital financial services, starting with payments; d) Greater availability, quality and adequacy of forms of financing for MSMEs (BCE, 2021).

According to Arregui Solano et al. (2020), the main causes that constitute obstacles to financial inclusion in Ecuador have to do with the absence of public policy incentives, economic informality, the lack of financial education in the population and distrust in banks. These factors drive individuals to desist from carrying out economic operations due to lack of resources or to turn to informal sources of financing that undermine their potential economic returns due to their high interests.

To measure financial inclusion, the guideline has been assumed to take data representative of the supply side and other data representative of the demand side of financial services. Those on the supply side relate to accessibility and use. For accessibility, indicators such as branches of banking and non-banking entities, ATMs and existing correspondents are considered. For use, the number of people who have one or more financial products for savings, credit, insurance or payment system are considered. Data on the demand side are extracted, above all, through national surveys at the household level; aspects such as choice, frequency of use, ownership over time, barriers or obstacles to using them, use of informal instruments, financial knowledge, financial attitudes and behaviors are considered, among others (OECD & CAF, 2020). For its part, the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV, 2009) proposes four groups of indicators: 1. Macroeconomic, 2. Access to financial services, 3. Use of financial services and 4. Barriers.

Two highly recognized methodologies applied worldwide to measure the situation of financial inclusion are:

Access to Financing Survey, developed by the International Monetary Fund, which analyzes a total of 40 quantitative indicators.

Global Findex survey coordinated by the World Bank. This considers three dimensions for the analysis: a) Financial access; b) Use of financial services and c) Financial well-being.

Ecuador's economic system is made up of four large sectors: private economy, public economy, mixed economy and popular and solidarity economy. The popular and solidarity economy has the so-called Organic Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy, which establishes the regulations for the sector.

The National Assembly of the Republic of Ecuador (2011) defines the popular and solidarity economy:

It is the form of economic organization, where its members, individually or collectively, organize and develop processes of production, exchange, marketing, financing and consumption of goods and services to satisfy needs and generate income, based on relationships of solidarity, cooperation and reciprocity, privileging work and the human being as the subject and purpose of its activity, oriented towards good living, in harmony with nature, over appropriation, profit and the accumulation of capital.

In turn, the popular and solidarity economy sector is divided into: real sector of the popular and solidarity economy and the financial sector of the popular and solidarity economy. The latter is defined in the law as follows, "the Popular and Solidarity Financial Sector is made up of savings and credit cooperatives, associative or solidarity entities, community banks and savings banks" (National Assembly of the Republic of Ecuador, 2011, p. 14).

So, the CACs are part of the financial sector of the popular and solidarity economy and are defined as follows: They are organizations formed by natural or legal persons who join together voluntarily for the purpose of carrying out financial intermediation and social responsibility activities with its partners and, prior authorization from the Superintendency, with clients or third parties subject to the regulations and principles recognized in this Law (National Assembly of the Republic of Ecuador, 2011, p. 14).

For Auquilla Belema et al. (2020), savings and credit cooperatives play a fundamental role in the country's economy because they are responsible for generating opportunities so that entrepreneurs can develop small and medium-sized businesses that contribute to the production and progress of the system. According to Luque González and Peñaherrera Melo (2021), "the emergence of associative or cooperative business organizations was not as novel as it was practical, but it was at a conceptual level, which is why it is frequently related to situations of poverty in depressed regions". These organizations were increasing their intervention in rural areas based on the needs raised by the inhabitants of said sectors.

The Superintendency of Popular and Solidarity Economy of Ecuador (SEPS in Spanish) categorizes savings and credit cooperatives according to their level of assets. Having in rank 1 the largest ones, in terms of financial capacity, and in rank 5 those with the smallest size and performance. According to SEPS figures, there are 494 organizations of this type around the Ecuadorian territory, distributed in the different segments mentioned, which allows the collection and placement of resources in millions of people, both in rural and urban areas; contributing to the development and development of productive activities in all their ramifications.

The research hypothesis states that the conditions of financial inclusion in the rural sector of the Guayaquil canton are insufficient according to national and international standards, while savings and credit cooperatives can have a favorable impact on the process.

The operationalization of the financial inclusion category is described below:

Variable or category: financial inclusion

Dimension 1: Access

Operational definition: "Capacity to use the financial services and products offered by formal financial institutions" (Working Group for the Measurement of Financial Inclusion, 2013).

Indicators:

Number of access points per 10,000 adults

Percentage of administrative units that have at least one access point

Percentage of total population that lives in administrative units where there is at least one access point

Percentage of adults with access to credit by type of provider

Percentage of adults with access to credit by type of provider (formal and informal)

Depth of adult access to formal credit products

Percentage of adults without credit according to reasons for rejection of the application

Percentage of adults with access to insurance products

Depth of adult access to insurance

Proportion of adults who regularly send and receive money orders and remittances

Average time in minutes to reach the sites where adults make transactions

Percentage of adults according to ownership of mobile devices

Percentage of adults according to ownership of fixed devices

Dimension 2: Use

Operational definition: "Depth or degree of use of financial products and services" (Working Group for the Measurement of Financial Inclusion, 2013).

Indicators:

Percentage of adults who have at least one type of regulated deposit account

Percentage of adults who have at least one type of regulated credit account

Percentage of adults with access to at least one financial product

Depth of adult access to formal financial services

Percentage of adults according to reasons for having the account they use the most

Percentage of adults according to reasons for not having an account

Percentage distribution of uses of formal financial credit

Percentage of adults according to reasons for not requesting a loan

Distribution of adults with access to insurance products

Payment methods used in different types of expenses

Dimension 3: Quality and consumer protection

Operational definition: Capacity to have public and private goods and services of optimal quality, to choose them freely, as well as to receive adequate and truthful information about their content and characteristics (National Congress of the Republic of Ecuador, 2000).

Indicators:

Percentage of adults according to banks' perception

Percentage of adults according to perception of cooperatives

Percentage of adults according to complaints

Percentage of adults according to satisfaction with the solution received

Dimension 4: Wellbeing

Operational definition: Relationship between access to formal financial services and products and the capacity of individuals to react to shocks that negatively affect the household economy (Banca de las Oportunidades & Superintendencia Financiera de Colombia, 2017, p. 6).

Indicators:

Materials and methods

As a theoretical method, the hypothetical-deductive method was applied. As theoretical procedures, analysis and synthesis to process theoretical information, as well as empirical data. Likewise, induction and deduction were applied in determining the study sample and the conclusions obtained from it. As empirical methods, the survey was applied, with a questionnaire that was the main instrument for data collection. It is worth mentioning that the review and analysis of documents was also used to note the current situation of savings and credit cooperatives in the Guayaquil canton, recognizing their importance, placement and recruitment volume, participation and other aspects that are key when it comes to understand the relevance of this form of organization for global financial intermediation activity. Both the users of the savings and credit cooperatives and the most representative of these entities in the territory were established as units of analysis, either due to their physical presence in the territory, or due to the commercial relationships they maintain. For procedural purposes, the Posorja, Puná, Tenguel and El Morro parishes of the Guayaquil canton were delimited as areas where information was collected through the survey. The Juan Gómez Rendon parish, part of the rural area of the canton, was excluded from the study due to the impossibility of accessing primary information on this occasion.

So, the delimitation of the population and the sample was derived from these four locations. Table 1 shows this information. In turn, interviews were conducted aimed at examining the position of the representatives of the savings and credit cooperatives and their clients, with a view to establishing the criteria of potential and limitations for financial inclusion.

Table 1 Study population

| Population* | Unit of measurement | 2010 | Participation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posorja | People | 14890 | 55.1 |

| Nose | 2647 | 9.8 | |

| Puna | 3306 | 12.2 | |

| Tenguel | 6174 | 22.9 | |

| Total | 27017 | 100.0 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador

*Corresponds to the population aged 18 and over

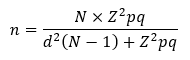

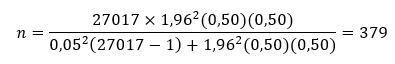

In the rural parishes of Posorja, Puná, Tenguel and Morro, a total of 27,017 people over 18 years of age reside, according to figures from the 2010 Population and Housing Census carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador. 55.1% live in Posorja, 9.8% in Morro, 12.2% in Puná and the remaining 22.9% in Tenguel. In this way, the population is classified as finite. The formula used to calculate the sample is the following:

The values to use to replace in the formula are presented below.

p Success ratio or expected ratio = 0.50

q Probability of failure = 0.50

Z Confidence coefficient for a given confidence level = 1.96

N Population size = 27017

d Maximum allowable error = 0.05

The expression was as follows:

When performing the corresponding calculation, it is determined that the sample for the study corresponds to 379 people. To select the individuals that make up the sample, a probabilistic and a non-probabilistic sampling method was applied consecutively. First, the cluster sampling method is applied, taking advantage of the distribution of individuals by parishes. To maintain similarity in the composition of the sample in relation to the population, the same proportions were applied. So, 55.1% of the individuals that make up the sample will be from Posorja, 9.8% from El Morro, 12.2% from Puná and 22.9% from Tenguel. There were 208 people from Posorja, 38 people from Morro, 46 people from Puná and 87 people from Tenguel. Then the non-probabilistic accidental or consecutive sampling method was applied in each parish.

Results and discussion

Current situation of financial inclusion in Ecuador

In Ecuador, the National Financial System is made up of 24 banks, 493 savings and credit cooperatives (all segments), 4 mutual societies and 2 public banks (BanEcuador and Corporación Financiera Nacional) (BCE, 2020). To establish the current situation of financial inclusion, the statistics presented by the BCE are used, highlighting the following data in table 2.

Table 2 Financial inclusion indicators. Fourth quarter 2020

| Entity | Number of clients | Number of accounts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial products | Active financial products | Unused financial products | Financial products | Active financial products | Unused financial products | |

| Private banks | 137165 | 84457 | 76591 | 366371 | 210663 | 155708 |

| Cooperatives of saving and credit | 27840 | 17451 | 13125 | 104776 | 50771 | 54005 |

| Others | 2106 | 2053 | 69 | 2690 | 2560 | 130 |

| National Financial System | 156231 | 97685 | 86850 | 473837 | 263994 | 209843 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on BCE (2020). Expressed in units

Note: There are cases in which the same client has more than one bank account

The National Financial System had around 156 thousand clients with financial products for the fourth quarter of 2020. Others 97,865 had active financial products, while another 86,685 were unused. Regarding the number of accounts, at least 473 had financial products, others 263 thousand with some active financial product and 209 thousand with unused products. Private banks are the ones that contribute the most to the financial inclusion environment at the national level, since they register more numbers of clients in each category, compared to savings and credit cooperatives, mutual societies and public banks, like the rest of the participants of the system. A similar case happens with the number of accounts. According to BCE (2021) figures, three out of every four Ecuadorian (between 18 and 69 years old) have access to financial products and services, which is equivalent to 8.5 million people. 51.8% are men and the remaining 48.2% are women. In addition, it points out that 72% of citizens has savings accounts, 4% checking accounts, 4%-time deposits and 28% of adults have some credit.

Focusing attention on CACs as an object of study, the following paragraphs will refer to the participation of these popular and solidarity organizations in the field of financial inclusion.

According to the SEPS report (2021), for the month of November there were 493 CACs in the country with 8.41 million contribution certificates nationwide, which maintains a default rate of 4.9% and a level of liquidity 27.9% of the portfolio amount. In global terms, the CACs recorded an asset level of USD 20,339 million, with a credit portfolio level of USD 14,315 million. The entities in segment 1 are the ones that contributed the most in every sense, considering that this category includes the most powerful organizations in the sector. It should be noted that there is a total of 4,113 service points of the popular and supportive financial sector in the Ecuadorian territory, with some 493 headquarters, 1,107 agencies, 182 branches, 1,523 ATMs and 808 other points. Regarding the contribution to financial intermediation, table 3 shows the amounts of deposits and placement according to the range of rurality and poverty of the country's cantons.

Table 3 Financial intermediation of the CACs. November 2021

| Category | Funding (Millions of USD) | Placements (Millions of USD) | Relationship (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rurality range of the canton | |||

| Less than 25% | 1868 | 2103 | 112.6 |

| From 25% to 49.9% | 10410 | 7524 | 72.3 |

| From 50% to 74.9% | 2913 | 2996 | 102.8 |

| Greater than or equal to 75% | 1083 | 1692 | 156.2 |

| Canton poverty range | |||

| From 25% to 49.9% | 10464 | 7151 | 68.3 |

| From 50% to 74.9% | 4338 | 4821 | 111.1 |

| Greater than or equal to 75% | 1472 | 2343 | 159.2 |

Source: Taken from SEPS (2021). Expressed in millions of dollars and percentages

Note: Rurality is understood as the relationship between the rural population compared to the total population of the canton

In localities where there is less than 25% rurality, the raising amounted to USD 1,868 million, compared to USD 2,103 million per placement, which establishes a ratio of 112.6%. That is, for every dollar that the CAC obtains through deposits in cantons with low rurality, they place USD 1.12 through financial products. For its part, in areas where rurality predominates, with at least 75%, the deposit was recorded at USD 1,083 million, with a placement sum of USD 1,692 million, which indicates a ratio of 156.2%. Establishing that, for every dollar raised, USD 1.56 is placed. So, the CACs obtain a greater impact, in terms of intermediation, in those rural areas of the country. On the other hand, regarding the analysis of poverty, in those cantons where this phenomenon affects a greater part of the population, popular and solidarity financial organizations captured USD 1,472 million and placed USD 2,343 million, exhibiting an index of 159.2%., which is far from what is recorded for the least poor cantons, where the recruitment-placement relationship reaches a figure of 68.3% (SEPS, 2021).

Regarding the distribution of service points, which amount to 4,113, in the provinces of Morona Santiago, Azuay and Carchi there is an index of service points per 10 thousand inhabitants, greater than 9 points, positioning itself as 3 of the locations with the greatest presence of popular and solidarity financial organizations in the country.

In other provinces, such as Zamora Chinchipe, Pastaza, Loja, El Oro, Tungurahua, Bolívar, Cotopaxi and Imbabura, an index that ranges from 4 to 9 points is maintained, with a presence of CAC and its medium-level service points. While, in the constituencies of Chimborazo, Galápagos, Napo, Pichincha, Santa Elena and Carchi, a low level of presence of these popular and solidarity forms is recorded, with an index between 2 and 4.

In Orellana, Guayas, Manabí and Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, the number of service points per 10 thousand inhabitants does not exceed two points. For its part, for Sucumbíos and Esmeraldas it is below unity, which classifies them as having a very low presence. As additional information, at the national level, there are 3.13 CAC service points per 10 thousand inhabitants (SEPS, 2021).

The SEPS reports (2021) show that at least 44.91% of adults have a deposit account, as well as 11.77% maintain current credit. Around 1.37 million people were subject to credit from the CACs for 2021, generating a total of loans close to 1.72 million, which recorded an average balance for each financial product of USD 7,407. This led to the closure the period with a global placement figure of USD 12,761 million.

Table 4 Volume of credit granted by the popular and solidarity financial system of Ecuador according to quintile. Year 2021

| Quintile | Granted Volume | Number of subjects | Number of credits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (millions of $) | Stake (%) | |||

| Quintile 1 | 493.06 | 7.90 | 122802 | 150139 |

| Quintile 2 | 727.31 | 11.66 | 118513 | 167848 |

| Quintile 3 | 1064.52 | 17.07 | 126430 | 191328 |

| Quintile 4 | 1469.32 | 23.55 | 125401 | 173379 |

| Quintile 5 | 2483.69 | 39.82 | 125021 | 172915 |

| Total | 6237.90 | 100.00 | 618167 | 855609 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on SEPS (2021)

Note: The volume of credit refers to the disbursements made for credits

As shown in table 4, in terms of placement, the CACs, as a whole, registered a credit volume of USD 6,237.90 million, through the request of 618 thousand subjects. The highest concentration of the amount occurred in the 5th quintile of the population, which corresponds to the demographic group with the highest income level. About UDS 2,483.69 million were allocated to this segment, equivalent to 39.82%. In quintile 1, where the families with the lowest income are found, the volume of credit assigned was US$ 493.06 million, having a participation of 7.90%.

Situation of financial inclusion in the rural sector of Guayaquil. Distribution of financial entities in the territory

The area studied, being rural, presents important limitations in terms of the existence of infrastructure of all types and, in particular, related to the financial and banking system. Table 5 summarizes the presence of the financial and banking sector in the territory with the information currently available.

Table 5 Service points available to carry out transactions and access products and services of the financial system in the different populations

| Point of service | Posorja | Morro | Puná | Tenguel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offices (headquarters, branches, agencies, counters, etc.) | 2 (Banco Pichincha, Jardín Azuay Savings and Credit Cooperative) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ATMs | 7 (Banco Pichincha, Jardín Azuay Savings and Credit Cooperative, Banco del Pacífico, Banco Bolivariano) | 0 | 0 | 1 (JEP Savings and Credit Cooperative) |

| Bonus and pension payment points of the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion | 22 (Jardin Azuay Savings and Credit Cooperative / Banco Pichincha / Banco Guayaquil) | 4 (Banco Guayaquil, Banco Pichincha, Jardín Azuay Savings and Credit Cooperative) | 2 (Guayaquil Bank, Pichincha Bank) | 49 (Guayaquil Bank, Pichincha Bank) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion (2021) and information offered by officials of the different Decentralized Autonomous Governments

The data collection instrument made it possible to identify different aspects related to four dimensions of analysis that were proposed for the measurement of financial inclusion in the study location: access, use, quality and consumer protection and well-being.

a. Access conditions

The impact of financial products on the respondents was examined, as well as the proximity to an establishment and the accessibility of communication and information instruments.

It was found that 60% of the subjects have not obtained credit from any financial intermediation institution, such as a bank or CAC, while 40% have. 48% stated that they had gone to a loan shark to obtain financing, another 52% had not done so. Likewise, it is considered that 72% of those surveyed do not currently have an active credit or loan, leaving only 28% to have this obligation.

On the other hand, the lack of a guarantor, a general requirement to obtain credit in most financial establishments, is the main reason why individuals do not access these products, with 38% of the distribution. Likewise, other causes are due to being located in the risk center, requiring very high amounts for their payment capacity, or not having an asset that serves as collateral.

Another aspect of the dimension has to do with insurance services, where 75% reported not having insurance of any type, only 25% reported having this mechanism. Hence, the majority of respondents do not have access to this system, while for those who do have the greatest place, it is in the formal financial sector (banks), being 13% and 8% for the formal non-financial sector (CAC).

23.3% of the people approached commented that they use third-party services to send or receive money, such as Western Union or Servipagos. The remaining 76.7% indicated that they do not receive any money through these channels. The majority have an access point less than 10 minutes from their residence, with another large percentage located more than 21 minutes from these establishments. A small group requires more than 41 minutes to visit a center of this type.

For their part, information and communication technologies have a marked participation in the social dynamics of the population consulted, while 90% have cell phones, 6.7% do not have them and 3.3% do not use them. A similar circumstance occurs with computers, since 55% do have this type of device, while 23.3% do not have it, but do use it.

b. Terms of use

The use of financial products and services by the population was investigated, as well as the purposes in the use of credits or insurance that are available to people.

Along these lines, it is noted that 43.3% of those surveyed do not have any type of savings or current account in a financial institution, 56.7% do. Likewise, 85.0% do not have a credit card at their disposal, compared to 15.0% who do have this instrument to meet their short-term financing requirements. In accordance with the above, 48.3% of individuals do not use any financial product such as a debit card or something similar, while 51.7% do. The financial service most used by the analysis population is over-the-counter deposits, with 76.7% of responses, followed by credits or loans with 8.3%.

In the case of people who have a savings or checking account, its main use is to receive money for salaries or debts receivable, as well as to save or pay debts. A small group indicated that they use these financial products to be subject to credit with the institution.

Among the reasons for managing a savings or checking account, the population's distrust of the financial system stands out, as well as the non-existence of agencies in the town that make it easier to obtain it. There is also the custom or preference for cash and the lack of knowledge about the procedure. While the factors that discourage the application for a loan are revealed by the high interest rates, the delay in approval, the lack of personal or collateral guarantees and the no need for financing with third parties.

The use of credits, by people who have used this service, was mainly directed towards productive investment, others towards health, purchase or improvement of housing or the acquisition of vehicles. In the case of contracting insurance, individuals stated that they would access this product mainly for life insurance, as well as health insurance or to safeguard agricultural production.

Transactionality in the sectors consulted is represented by the use of cash as a means of payment and collection. At least 76.9% of those surveyed indicated this form as their favorite. However, there are also people who use debit or credit cards, as well as transfers.

c. Quality and consumer protection

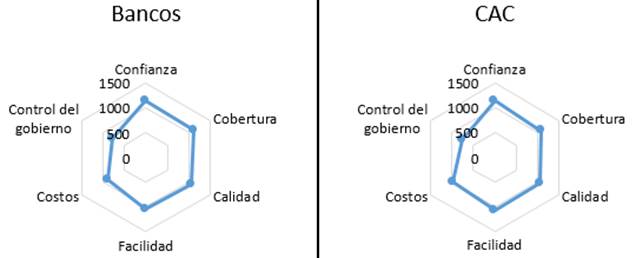

The perception of consumers in relation to the financial services offered by financial organizations in the localities was investigated. To determine the score for each dimension, a rating from 1 to 5 was given to the rating scale (very bad=1, bad=2, fair=3, good=4, very good=5), then multiplied by the corresponding frequency for each case. So, the maximum possible score value for each dimension would be 1895 (379 times 5), given a total rating of very good in one category.

The banks' evaluation is relatively good in terms of trust (1142), quality (1064), coverage (1109) and ease of access (1031). Costs (891) and Government control (769), for their part, had a rather poor assessment. Similarly, CACs register a better score than banks in trust (1148), ease and costs (1070), but not with coverage (1075), quality (1053) or government control (741).

Overall, CACs end up being better evaluated than banks. The CACs reach 6073 points while the banks reach 6006 points. The greatest difference is found in the "costs" dimension, being 95 points in favor of the cooperatives.

41.7% of those surveyed are satisfied with the way these institutions operate, 28.3% are indifferent, another 20% are dissatisfied with this, 8.3% say they are very satisfied and the remaining 1.7% very dissatisfied.

Figure 1 shows the evaluation results of both the banks and the CACs in comparison.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on a survey carried out

Source: Prepared by the authors based on a survey carried outFigure 1 Respondents' appreciation of different aspects of banks and CACs

d. Wellbeing

In the last dimension of analysis, concerned with the well-being of the clients of the formal and informal financial system, an attempt was made to find out how people act in the event of a possible emergency or request for financing, in order to determine the degree of acceptance and openness towards these sources of intermediation as an alternative solution.

In this sense, when there was a case where money was required, 45% indicated that they resorted to a loan to cover their pressing situation. Another 25% used their own savings. In lesser cases, they resorted to selling assets or collecting through family or friends, or using raffles, among others. Consequently, the form of informal financing, warned by usurers or family loans, was the main way to cover people's needs. In 18.3% of the cases they went to banks or cooperatives in the formal financial sector, while 8.3% did so through organizations in the formal non-financial system, where savings banks and community banks are located. Likewise, the search for obtaining money through raffles and sales of goods stands out, accounting for 11.7% of the cases.

Potentials and limitations of savings and credit cooperatives to promote financial inclusion in the rural sector of Guayaquil

Table 6 shows the results obtained after applying interviews to actors in the popular and solidarity financial sector, in its CAC dimension, where they presented their comments about the environment in which these organizations operate, which allowed them to define a set of potentialities (strengths + opportunities) and limitations (weaknesses + threats) in the segment and from them determine actions to maintain, correct, exploit and address these circumstances respectively. Seven officials from five savings and credit cooperatives were interviewed, some of them with a presence in the study territory and others who could potentially access it; these officials hold positions of agency and branch leadership.

Table 6 Potentials, limitations and possible actions to apply

| Potentials | Limitations | Possible actions to apply |

|---|---|---|

|

Acceptance of CCS in the rural setting Approach of the CAC to the associative and solidarity field High demand for financial services in rural areas Own legal framework for CACs Productive credits favorable to farmers Restructuring of interest rates Development of primary activity Demand for new branches of financial establishments Territorial coverage |

High presence of informal financial services People's trust in the banking financial system Disappearance of low-segment cooperatives by decree High non-performing portfolio Lower asset level than a bank The participation of public banks with low interest loans CAC expansion of low segments to affect market competitiveness Procrastination risk Contraction of the national economy |

Design advertising campaigns to show the advantages of CAC financial services Fully align with the principles of popular and solidarity economy and finance Maintain and expand financial services coverage in rural parishes Improve facilities in rural establishments Target interest rates, terms and amounts for farmers for mutual benefit Request the authorities to control informal lenders Guarantee shorter times for arranging credits Offer payment agreements for overdue portfolios Create competitive financial products Establish competitive strategies in attention times and costs |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on interviews with actors in the popular and solidarity financial sector

Throughout these results, it is possible to determine the degree of inclusion to which the inhabitants of the rural area of Guayaquil adhere, who have, in many cases, the use of at least one type of financial product or service, which already envisions a minimum of financial inclusion. Likewise, it was possible to elucidate the perception of citizens regarding the development of CACs, which offers a positive assessment of their actions, in comparison to banks.

In this way, it is possible to state that the contribution of the CACs to the financial inclusion of the population of Posorja, Morro, Tenguel and Puná is fair, because the financial products and services offered do not manage to capture the attention of individuals since they do not make effective use of them, but they can do so with informal financing or from their own sources.

Referencias bibliográficas

Arregui Solano, R., Guerrero Murgueytio, R. M., & Ponce Silva, K. (2020). Inclusión financiera y desarrollo. Situación actual, retos y desafíos de la banca. Universidad Espíritu Santo. http://repositorio.uees.edu.ec/handle/123456789/3208 [ Links ]

Asamblea Nacional de la República del Ecuador. (2011). Ley Orgánica de Economía Popular y Solidaria. Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria. https://www.seps.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/Ley-Organica-de-Economia-Popular-y-Solidaria.pdf [ Links ]

Auquilla Belema, L. A., Sancho Aguilera, D., Ordóñez Bravo, E. F., Fernández Sánchez, L. del R., Cadena Oleas, B. N., & Auquilla Ordóñez, Á. A. (2020). El papel de las organizaciones de finanzas populares y solidarias en el desarrollo de los emprendimientos locales en Ecuador. Estudio de caso. Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina, 8(3). https://revistas.uh.cu/revflacso/article/view/5378 [ Links ]

Banca de las Oportunidades & Superintendencia Financiera de Colombia. (2017). Estudio de demanda de inclusión financiera. Informe de resultados segunda toma 2017. Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina. https://www.bancadelasoportunidades.gov.co/sites/default/files/2018-08/II%20ESTUDIO%20DE%20DEMANDA%20BDO_0.pdf [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2018). Según la base de datos Global Findex, la inclusión financiera está aumentando, pero aún subsisten disparidades. https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/press-release/2018/04/19/financial-inclusion-on-the-rise-but-gaps-remain-global-findex-database-shows [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2022). Inclusión financiera. https://www.bancomundial.org/es/topic/financialinclusion/overview [ Links ]

BCE. (2012). Inclusión financiera. Aproximaciones teóricas y prácticas. Banco Central del Ecuador. https://contenido.bce.fin.ec/documentos/PublicacionesNotas/Catalogo /Cuestiones/Inclusion%20Financiera.pdf [ Links ]

BCE. (2020). Estadísticas de Inclusión Financiera. Banco Central del Ecuador. https://contenido.bce.fin.ec/home1/economia/tasas/indiceINCFIN.htm [ Links ]

BCE. (2021). Estrategia nacional de inclusión financiera 2020-2024. Banco Central del Ecuador. https://rfd.org.ec/docs/comunicacion/DocumentoENIF/ENIF-BCE-2021.pdf [ Links ]

CNBV. (2009). Informe anual 2009. Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores de México. https://www.cnbv.gob.mx/TRANSPARENCIA/Transparencia-Focalizada/Documents/Informe%20Anual%202009%20PDF.pdf [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores de México. (2020). Inclusión financiera. https://www.gob.mx/cnbv/acciones-y-programas/inclusion-financiera-25319#:~:text=La%20CNBV%20realiza%20las%20siguientes,uso%20del%20sistema%20financiero%20formal [ Links ]

Congreso Nacional de la República del Ecuador. (2000). Ley orgánica de defensa del consumidor. https://www.dpe.gob.ec/wp-content/dpetransparencia2012/literala/BaseLegalQueRigeLaInstitucion/LeyOrganicadelConsumidor.pdf [ Links ]

Grupo de Trabajo para la Medición de la Inclusión Financiera. (2013). Medición de la inclusión financiera. Conjunto principal de indicadores de inclusión financiera. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/69640/Indicadores_AFI.pdf [ Links ]

Luque González, A., & Peñaherrera Melo, J. (2021). Cooperativas de ahorro y crédito en Ecuador: El desafío de ser cooperativas. REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, 138, e73870. https://doi.org/10.5209/reve.73870 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social. (2021). Punto de pago de bonos y pensiones del Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social. https://www.inclusion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2021/01/Guayas-1.pdf [ Links ]

OCDE & CAF. (2020). Estrategias nacionales de inclusión y educación financiera en América Latina y el Caribe: Retos de implementación. Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos / Corporación Andina de Fomento. https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/Estrategias-nacionales-de-inclusi%C3%B3n-y-educaci%C3%B3n-financiera-en-America-Latina-y-el-Caribe.pdf [ Links ]

Pérez Caldentey, E., & Titelman Kardonsky, D. (2018). La inclusión financiera para la inserción productiva y el papel de la banca de desarrollo. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/44213-la-inclusion-financiera-la-insercion-productiva-papel-la-banca-desarrollo [ Links ]

Raccanello, K., & Herrera Guzmán, E. (2014). Educación e inclusión financiera. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 44(2), 119-141. https://doi.org/10.48102/rlee.2014.44.2.250 [ Links ]

Rosado, J., Villareal, F. G., & Stezano, F. (2020). Fortalecimiento de la inclusión y capacidades financieras en el ámbito rural: Pautas para un plan de acción. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/45115-fortalecimiento-la-inclusion-capacidades-financieras-ambito-rural-pautas-un-plan [ Links ]

SEPS. (2021). Cifras de la Economía Popular y Solidaria. Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria. https://www.seps.gob.ec/actualidad-y-cifras/ [ Links ]

Sierra Lara, Y., Rosales Valencia, J. E., & Rosales Barzallo, F. I. L. (2024). El estado de la inclusión financiera de un grupo de mujeres emprendedoras en El Morro: Caso de Extensión UPS. Boletín de Coyuntura, (40), 37-47. https://revistas.uta.edu.ec/erevista/index.php/bcoyu/article/view/2331 [ Links ]

Received: October 30, 2023; Accepted: March 26, 2024

texto en

texto en