Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3469

Rev CFORES vol.11 no.3 Pinar del Río sept.-dic. 2023 Epub 07-Sep-2023

Original article

Social perceptions of the agroecological transition process in coffee-growing families of Guadalupe, Huila

1Universidad de la Amazonia, Florencia, Colombia.

2Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

The context of the research is the coffee monoculture in Huila and its point of analysis is those Laboyana peasant families that carry out these agroecological transition processes. The objective of the research was to analyze the social perceptions that coffee-growing peasant families from a rural community in the department of Huila in Colombia have about their agroecological transition process from conventional coffee cultivation to a crop with agroecological principles. The methodology used is a qualitative and ethnographic approach, a case study in the Los Cauchos village, in the Municipality of Guadalupe, where coffee-growing families were interviewed about their perception of the agroecological transition process. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, categorized and the findings were written up. As part of the results, it was found that for coffee-growing households, four determining components in the agroecological transition process of their agroecosystem are: 1) technical-productive, 2) economic, 3) socio-humanistic, and 4) practical knowledge, linking care, effort, dedication, patience, support networks, stigmatization and frustration as significant concepts to understand their agroecological process. By way of conclusions, there is that locally there is a struggle between two conceptions of agriculture, one naturalized and with an entire institutional and market apparatus, and another initial one that opens spaces for a better location within the market and with greater incidence in the administrative sphere. and social relations in Guadalupe, Huila.

Key words: Agriculture; peasants; market; agroecology; support networks.

INTRODUCTION

Peasant families in Colombia have experienced a series of historical and systematic challenges, including exclusions and violence perpetrated by various actors, both state and parastatal (Higuera, 2022). These difficulties, exacerbated by the armed conflict, lack of education and a deficient state presence, have profoundly impacted their lives and agricultural practices. The Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History-Icanh (2017) describes how the peasantry has evolved in response to changes in capital accumulation and associated livelihoods, implying a diversity of origins and trajectories.

Focusing on Guadalupe, Huila, we find that farmers have developed survival strategies in an environment marked by economic and political challenges. According to Sanabria (2022), these strategies include reflections on their dependence on the market, the use of pesticides and the effects of climate change. These reflections, resulting from the interaction between different actors such as farmers, extensionists and ecologists, have fostered a movement towards agroecological practices. Ospina (2021) defines agroecology as a broad theoretical framework that transcends the scientific discipline to include a set of practices and a social movement.

The present study focuses on farming families in Guadalupe who are transitioning to agroecology, with the objective of understanding the challenges and opportunities they face in this process. For this, it is crucial to review previous works at regional, national and local levels, such as those of Nicholls and Altieri (2016, cited by Benavides, 2022), which examine agroecological principles beyond practices such as composting or crop rotation, focusing on aspects such as nutrient recycling and water and soil conservation.

At the Latin American level, studies in Cuba (Lucantoni et al., 2018, cited by Benavides, 2022) and Mexico (Duché et al., 2017, cited by Benavides, 2022) highlight how agroecology is intrinsically linked to food security and sovereignty. These works highlight the importance of understanding agroecological practices in the context of the culture and social structure of communities.

At the local level, research such as Gómez et al. (2018) and Franco (2011), cited by Benavides (2022), highlight agroecological initiatives in various Colombian communities, providing concrete examples of transition to more sustainable practices.

This research aims to fill a knowledge gap on agroecological transition in Guadeloupe, especially in the context of coffee monoculture. It will take into account the interdisciplinary nature of agroecology, ranging from tropical ecology to sociology and anthropology, to understand the rationality of traditional systems and the relevance of social organization in the productive process (García 2000; Altieri 1992; Altieri 1992; Altieri and Nicholls, 2000; Gilessman, 2002; Sevilla-Guzmán 1998.

The study seeks to provide knowledge and accurate data on agroecological transition experiences in Guadeloupe, emphasizing the role of farming families in the transformation of coffee agroecosystems towards more sustainable and ecologically responsible practices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This exercise was carried out in the Corregimiento Bruselas, vereda Los Cauchos, located in the municipality of Guadalupe-Huila. This municipality is located in the Magdalena valley and between the central and eastern mountain ranges, has an area of 242,000 km2 , and a population that according to DANE projections reaches 19,266 inhabitants.

The paradigm from which this project was positioned is the historical-hermeneutic, which focuses or privileges an immersion in the context being studied, this implies putting in tension the creative and analytical capacities and social sensitivity as a researcher, since it is the social reality itself that is being investigated (Martínez, 2020).

The method included visits and field visits to 12 coffee farms in the district.

Brussels, who depend exclusively on coffee cultivation for their livelihood and when there is no bean harvest, they sell their labor on neighboring farms.

In order to understand the relationship of the families with the coffee agro-ecosystem, the technique of participant observation was used, accompanying and recording the diverse activities that the families carry out around the cultivation of coffee, and then proceeding to conduct an in-depth interview in order to learn about their process of agroecological transition from a coffee monoculture with conventional principles to a coffee cultivation with agroecological principles.

The interview addressed past, present and future scenarios and within them, limitations, satisfactions, challenges and experiences of the process. This information, which was collected by audio recording, with prior authorization from the interviewees, was transcribed in its entirety and an exploratory analysis was carried out, firstly, with the output diagram being a word cloud and then a deductive analysis, following the protocol of Bonilla-Castro and Rodriguez (1997), -In this case, the output diagram used were network diagrams, with the help of the qualitative data processing software Atlas ti, version 9.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Exploratory analysis

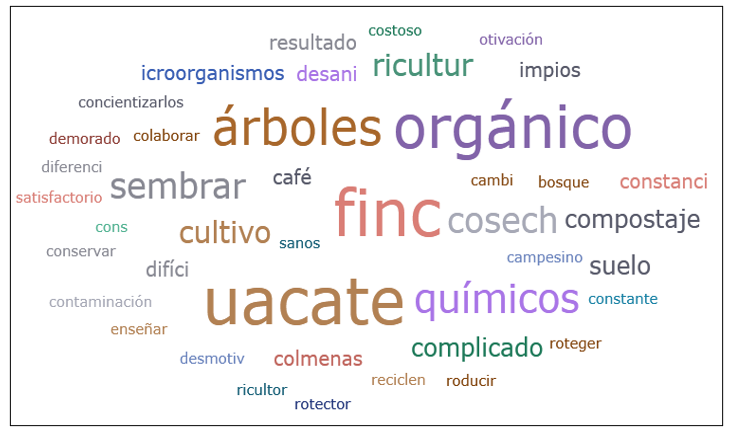

When analyzing the data constructed in the field, at first glance and from the word cloud, 43 words stand out that, in a recurrent way, give clues to the main concerns of the interviewed subjects. It is possible to point out, mainly, "organic", "trees", "crops", "harvests", "avocado", "farm", "chemicals", "complicated", "constancy". Precisely, in these words it is understood that the narratives oscillate between their life and work experience and with the crops, but at the same time they frame it in the complexity and constancy of what it implies to make the agroecological transition (Figure 1).

The social perception of the agroecological transition process, in the narrative presented by the interviewees, yielded about 36 codes of analysis that show, on the one hand, a propositional, affective and practical sense, and on the other hand, the tension generated by the transition experience. These feelings were grouped into 4 families of analysis as shown below.

Family 1. Farmer's perception of the transition process

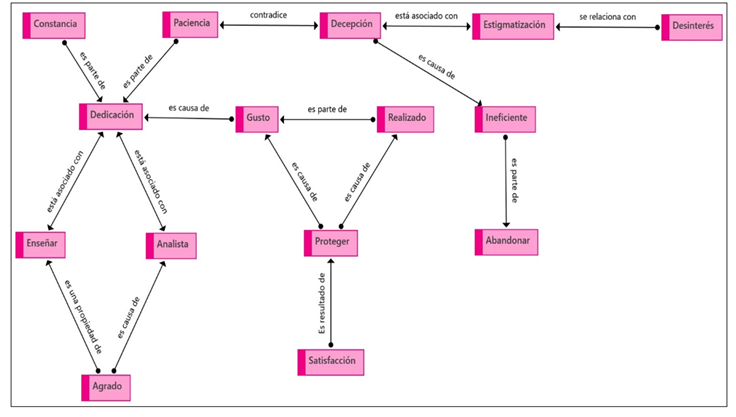

There is a struggle between satisfaction and disappointment, affections that mobilize people to generate a series of practices such as the teaching of knowledge, the protection of ecosystems and the implementation of processes. The transition forces constancy when looking for these alternatives, this constancy must be linked to a sense of patience and change of perspective with respect to crops. For Rojas (2017), it is in the relationship between the needs of society to advance in emancipatory and autonomous processes, where the territory is built, in the framework of a struggle for its ideals, even when this implies change in the ways of thinking, acting and relating.

It is in the day to day, second by second, a patient and attentive relationship, which is tasted and taught, since this position goes against the accelerated forms of the agrochemical. Here one waits and observes, seeks and cares. Thus, protection is fundamental for these narratives, from patience and the transmission of knowledge, protection both at the ecosystemic and own level, and it is that the organic in these perceptions comes from an idea of transversal care, since cultivating in a "clean" way is understood both as helping the ecosystem, as well as the body itself by providing it with uncontaminated food. According to Miranda et al. (2019) argues, for the case of some families in Chigorodó, how to cultivate has meanings that show dedication, interest and above all self-care, since it is necessary to "occupy time, feel tranquility, reduce stress and avoid monotonies of work" (p.180).

However, it is also a struggle between those who look in from the outside and nominalize it negatively, as inefficient. This leads to feelings such as discouragement, on the one hand, and disappointment when results are not observed immediately, on the other, which in most cases points to a sense of abandonment. For the case of Chigorodó, a similar situation is found where the products when sold face the situation of low valuation, which in many cases leads to the abandonment of such sales practice, and it is developed for self-consumption (Miranda et al., 2019).

However, it is important to mention that there are a series of imaginaries that stigmatize these agroecological processes, which generate among those who undertake the transition a struggle for new meanings for their processes and, above all, destabilize the disinterest of people and local institutions. Despite the fact that these struggles wear down those who develop them, they can be understood as energizing, since they allow the subjects to think about their agroecological transitions (Figure 2).

Family 2. Technical-productive concepts

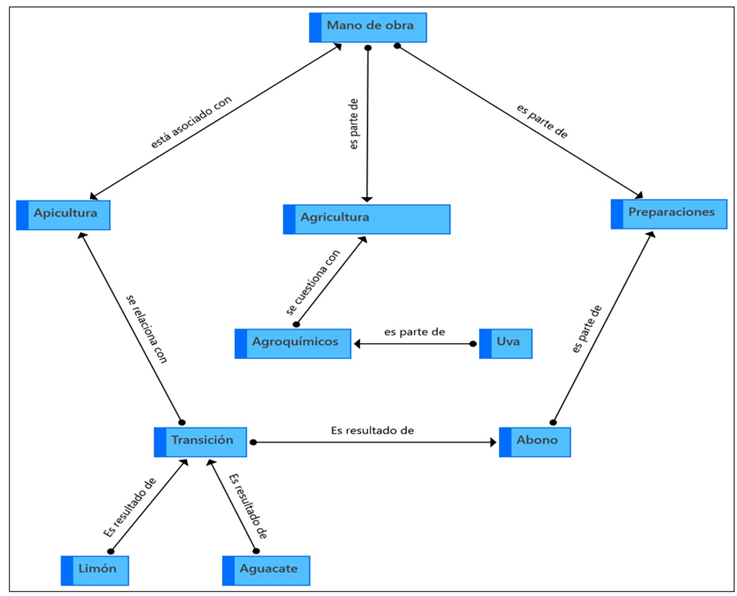

For this family, it could be mentioned the existence of a rupture in what has been traditionally understood as agriculture, with a total or partial distancing between agrochemicals and the alternative forms of production being carried out by the peasant families interviewed. It is related how a family father sustains a grape crop in a section of the farm, adding traditional fertilizers and spraying it with glyphosate, it is pointed out how that small part is deteriorated by such management, compared to the other parts managed with organic production. For Rojas (2017) that distancing from traditional agriculture, where agro-toxic is understood as eating badly, and agroecological in eating/producing clean, and the peasant women who have attended the agroecological school, mean an improvement in their living conditions.

However, the codes of this family show process, movements and constant transformations. In the first place, labor plays an important role, since this agroecological journey involves many people and activities where, on the one hand, beekeeping breeding and maintenance are managed, which is linked to crop pollination processes and insect care, and on the other hand, to the different preparations. It is important to understand that the latter code refers to all organic materials, inputs, knowledge, developments and applications. In other words, a bio-fertilizer is a preparation, but also the place and the way in which it is developed, it can also be organic herbicides, bioinsecticides, etc.

González and Herrera (2008) argue that the Indo-Campesino communities of the Yucatán have a complex system of interaction with bees, which they have been managing since pre-Hispanic times, where honey production is favored by the implementation of other crops, thus diversifying the production of family units.

On the other hand, this dynamic of preparations, fertilizers, labor, beekeeping, is connected with the ideas of transition. Thus, agroecological transition is not a general and finished process, but arises in the interaction between subjects, knowledge, animals and plants, which are geographically, historically and culturally located in a specific place. So, for this particular case, it is possible to follow the transition through the avocado and lemon crops mentioned by the actors in their experiences. These crops brought into play knowledge, working dispositions and emotions since, in the technical-productive field, the climate played strongly against the avocado, while with the lemon the experience was more satisfactory, even leading to export negotiations to other countries (Figure 3).

Family 3. Practical knowledge

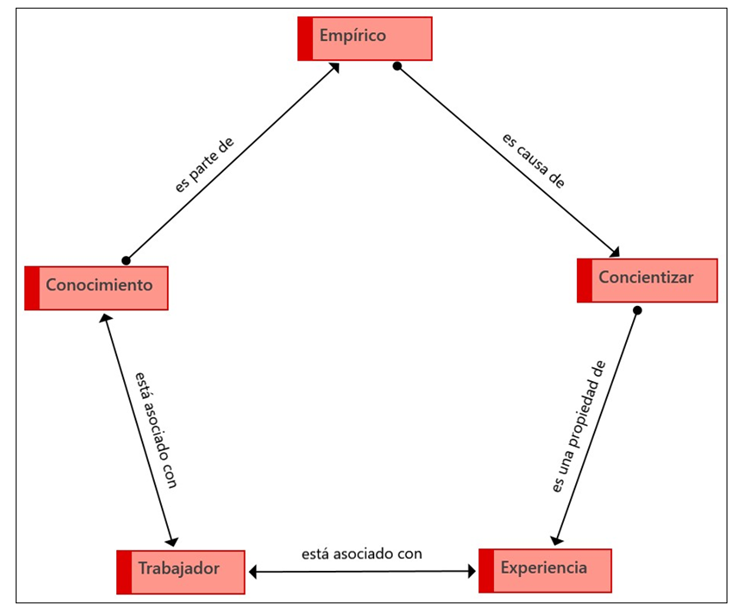

Although we have previously touched a little on issues of knowledge, in this family the place of knowledge in such agroecological transition processes is precisely addressed. It should be pointed out that there is a complementarity between what is taught theoretically in courses at SENA or rural extension in the area and what is learned in the empirical sphere. All knowledge must be put into practice and adjusted for each productive process, and some biofertilizers may even have better applications than the recommendations in the manuals. The dialogue between empirical and scientific knowledge, nourished by experience, allows the generation of other sensitivities, because whoever learns and does what he learned, whoever shares such knowledge and is willing to place the resulting complications, whoever exercises and does such knowledge on a daily basis, is the one who generates a network of awareness towards agroecology.

But this process of raising awareness is not only about saying that agrochemical agriculture is bad and the other is good, but also about creating networks that transmit knowledge, doubts and concerns, but also solutions in most cases. For Dalmoro et al. (cited by Miranda et al., 2019) there are logics specific to this type of agriculture, where they are built from beliefs, traditional practices, values, symbologies, etc., which in one way or another strengthen the ways in which the participants' own knowledge is solidified (Figure 4).

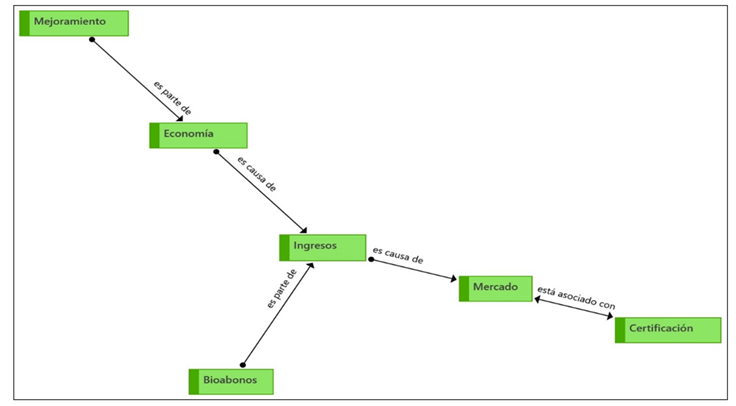

Family 4. Economy

This section deals with an important aspect for the interviewees, precisely the economic aspect. It is fundamental the place of income for the subjects, since it is looked in front to have income for a better sustenance. However, it is necessary to bring up the problems related to the economy, where in many occasions the products were not sold at an optimal price, even emphasizing that those who bring "contaminated" crops, even have better sales than organic products. This is due to the few communication and support networks in Guadeloupe in the commercialization since, on the one hand, there is a requirement to sell with the "organic" catalog and that is to have a certification, which is extremely complicated if it is an individual process and without organizational support. On the other hand, the local market does not encourage all the extra work done in "clean" crops, so much so that support has to be sought in other departments and even from foreign locations.

According to Cadena (2009) in his study of the "new ruralities" in Colombia, he argues about the "ecological coherence" where production not only faces the market, but also the ecological and organizational aspects, combining cultural, social and environmental aspects, which stresses the places where the products are marketed and precisely these networks must expand to national or international levels. Both this aspect and the one seen in Guadeloupe are in dialogue and intertwine in their challenges and difficulties (Figure 5).

In dialogue with the above, the idea of not spending too much, of making economy, is also preponderant, since, if an agroecological transition is carried out, the strong point is to minimize expenses. This idea gives strength to the idea that any clean crop must also reduce unnecessary consumption. The above addresses inputs for the construction of an improvement at the level of the approach to any crop, where it is not spent but only on what is necessary, and if fertilizer is needed, the bio-fertilizers should be composed of materials that the farm itself provides. Thus, this ethical dimension is fundamental in the economic, and it should be said that, in Cadena (2009), consonances are found, where the author mentions that inquiring about Colombian ruralities has implied seeing beyond the productive technical, and anchors her position in the ethical-normative since "it is a process supported by cultural plurality, socio-political equity, decentralization and citizen participation" (p.8).

CONCLUSIONS

In the first place, there are spaces within this municipality where meanings, markets and places for agricultural production are disputed, the agroecological transition for these families has meant learning knowledge, dialoguing with other people and putting it into practice on their farms. That is to say, the contact and the doing with the other, mediated by an agroecological posture, shows a patient, slow, careful, thoughtful will, which clearly contradicts the dynamic, fast and immediate of agrochemicals, which ultimately ends up being a critique of the thinking of capitalist modernity.

This critique is articulated with an ethics of transversal care, pondering what is clean, what is thought through trial and error against what is contaminated both in the body and in production. This ethic also dialogues with animals, insects and plants, listening to them and understanding them in their relational dimensions with the farmer, who in most cases tries to involve more people to position themselves within this network.

Finally, a different sense of economy can be inferred, positioning low spending, self-production, support networks and the teachings of knowledge that in one way or another point to a dignified and non-codependent life. It is on these points that research on agroecological transitions should emphasize, since any critique of capital is a stance to build better lives to live.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

ALTIERI, M.A., 1992. ¿Por qué estudiar la agricultura tradicional? La tierra, mitos, ritos y realidades: coloquio Internacional. Granada, 18/04/1991, Anthropos, ISBN 84-7658-365-6, pp. 332-350 [en línea]. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=560642. [ Links ]

ALTIERI, M.A., y YURJEVIC, A., 1992. La agroecología y el desarrollo rural sostenible en América Latina. AMBIEN-TICO [en línea], no. 22. Disponible en: https://www.ambientico.una.ac.cr/wp-content/uploads/tainacan-items/5/1578/22_2-12.pdf. [ Links ]

BONILLA-CASTRO, E., y SEHK, P.R., 1997. Más allá del dilema de los métodos: la investigación en ciencias sociales [en línea]. S.l.: Ediciones Uniandes. ISBN 978-958-9057-72-8. Disponible en: https://books.google.com.cu/books/about/M%C3%A1s_all%C3%A1_del_dilema_de_los_m%C3%A9todos.html?hl=es&id=oSa54vNsC7YC&redir_esc=y. [ Links ]

CADENA DURÁN, O.L., 2009. Aportes conceptuales para un análisis de la producción orgánica, elemento transformador de la nueva ruralidad. Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial: BSAA [en línea], vol. 7, no. 2 (julio a diciembre), [consulta: 22/09/2023]. ISSN 1909-9959, Disponible en: Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6117988 . [ Links ]

CARRILLO, E.L.H., 2022. Aspectos clave en agroproyectos con enfoque comercial: Una aproximación desde las concepciones epistemológicas sobre el problema rural agrario en Colombia. Región Científica [en línea], vol. 1, no. 1. ISSN 2954-6168. DOI 10.58763/rc20224. Disponible en: https://rc.cienciasas.org/index.php/rc/article/view/4. [ Links ]

GARCÍA, T. R. 2000. La Agroecología: ciencia, enfoque y plataforma para su desarrollo rural sostenible y humano. Revista "AGROECOLOGIA". [ Links ]

GLIESSMAN, S.R., 2002. Agroecología: procesos ecológicos en agricultura sostenible [en línea]. S.l.: CATIE. ISBN 978-9977-57-385-4. Disponible en: https://biowit.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/agroecologia-procesos-ecolc3b3gicos-en-agricultura-sostenible-stephen-r-gliessman.pdf. [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ, J., 2020. La interseccionalidad como herramienta analítica para la praxis crítica del Trabajo Social. Reflexiones en torno a la soledad no deseada. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social [en línea], vol. 33, no. 2, [consulta: 22/09/2023]. ISSN 1988-8295. DOI 10.5209/cuts.65181. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/CUTS/article/view/65181 . [ Links ]

MIRANDA HERNÁNDEZ, Y., SÁNCHEZ GONZÁLEZ, A., MACHADO SUÁREZ, L. Y., & RODRÍGUEZ VILLAMIL, L. N. 2019. Significados y usos que los habitantes de una vereda en Chigorodó, Antioquia, Colombia, dan a los alimentos que producen.Perspectivas En Nutrición Humana, vol 21 no. 2, pp. 173-187. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.penh.v21n2a04 [ Links ]

OSPINA, D.T., 2021. Las economías campesinas en Colombia. Tensiones y desafíos. Algarrobo-MEL [en línea], vol. 10, [consulta: 22/09/2023]. ISSN 2344-9179. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs3/index.php/mel/article/view/5312 . [ Links ]

ROJAS, Y.L., 2017. Mercados orgánicos: propuesta de seguridad alimentaria y desarrollo rural. El caso de la Asociación Red Agroecológica Campesina en Subachoque, Cundinamarca. [Proyecto de investigación, Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia UNAD]. [en línea]. S.l.: Repositorio Institucional UNAD. Disponible en: https://repository.unad.edu.co/handle/10596/13648. [ Links ]

SEVILLA GUZMÁN, E., 1998. EL Marco Teórico de la Agroecología. En Materiales de Trabajo del Curso "Agroecología y Conocimiento Local". Universidad La Rábida, 20/01/1998, p.3-28. [ Links ]

Received: April 25, 2023; Accepted: August 04, 2023

texto en

texto en