INTRODUCTION

The fruits of the Capsicum genus (chili pepper) are worldwide used in food and pharmaceutical industry mostly due to its pungent taste, flavor, and pigments (Krishna 2004, Mohd Hassan et al., 2019), and its pharmacological and nutraceutical properties (Materska and Perucka 2005, Hue and Dong 2010). Five Capsicum species have been recognized as domesticated: C. annuum (L), C. baccatum (L), C. chinense (Jacq.), C. frutencens (L) and C. pubenscens (Govindarajan 1985, Kraft et al., 2014). The pungent taste is due to capsaicinoids (Iwai et al., 1979), and the pigment color, usually yellow, orange, o red, is due to carotenoids (Sing de Ugaz, 1997, Mohd Hassan et al., 2019). Capsaicinoids is a group of pseudoalkaloid compounds synthesized and accumulated in the epidermis cells of the placental tissue through the condensation of vanillylamine, from phenylalanine, with a group of ω-1-methyl-fatty acids of nine to eleven carbons, biosynthesized from valine or leucine, catalyzed by the enzyme capsaicinoid synthetase (Fujiwake 1980, 1982a, b, Suzuki 1981). The Capsicum pigments, namely, capsanthin, capsorubin, β-carotene, β -cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, antheraxanthin and violaxanthin, are biosynthesized from pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphae through the plastid localized methyl-erythriol-phosphate biochemical pathway by condensation of two molecules of Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) by phytoene synthase (PSY) to form phytoene (Mohd Hassan et al., 2019). The biosynthetic pathways and variations of both pungent and carotenoids compounds regarding to the growth stage of Capsicum fruits has been extensively, but individually, examined (Iwai et al., 1979, de Azevedo‐Meleiro and Rodriguez‐Amaya, 2009, Mohd Hassan et al., 2019); however, synchronization and relationship between biosynthesis, degradation and/or turnover of both group of compounds regarding to the stage of maturation have received no attention. In consequence, it has been though that capsaicinoids may be highly involved as signal for trigger other metabolic pathways, such carotenoids, acting as biochemical signal for the fruit's elongation and development. In this work, the relationship between the accumulation of these two group of compounds during the growth and ageing processes of several Capsicum species was examined to instigate if a possible biochemical relationship between the variation of these two group of compounds during the ripening and senescence processes of several Capsicum species may exist.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fruits Fruits of several species of Capsicum in different stages of maturation were harvested from plants cultivated in greenhouse.

Capsaicinoids Extraction of phenolic compounds was performed with ethanol from placental tissue ground in the presence of liquid nitrogen.

Pigments Carotenoids were extracted with acetone from pericarp ground in the presence of liquid nitrogen, followed by liquid-liquid extraction with ethyl ether. The ethereal fraction was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, mixed with 10% NaOH in methanol in a 1:1 ratio, neutralized with HCl, and extracted with ethyl ether again. The organic fraction was evaporated to dryness and the remainder was resuspended in absolute ethanol.

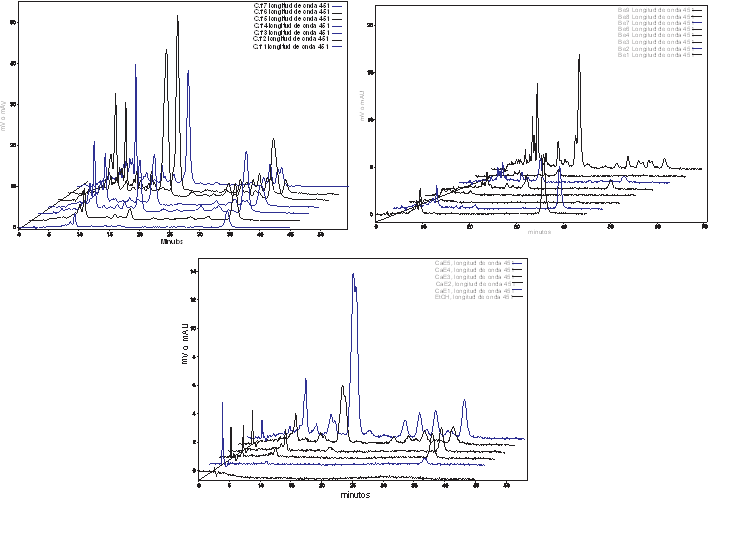

HPLC-UV analysis Quantification, separation and UV spectral analysis of the phenolic and carotenoid extracts were performed by HPLC-UV as reported in (Calva et al., 1995), and (Martínez-Juarez et al., 2004). The HPLC system included a binary pump (Thermo Separation P2000), a self-sampler (Thermo Separation AS1000) with a fixed 20 μL loop and a UV/Visible scanning detector. The detector signals were captured and processed by the PC1000 (Thermo Separation Products) software. This software includes programs for quantitative and spectral analysis. For both phenolics and carotenoids, the separation of the compounds in the extracts was carried out with a Phenomenex ODS2 column, 5 μM, 200x4.5 mm (Cheshire, Englad), flow 1 mL/min. For phenolics and capsaicinoids the gradient of A, trifluoroacetic acid 1 mM, and B acetonitrile was: [Time (min)-A (%)] 0-90, 5-80, 10-80, 25-80, 35-40, 55-40, 60-10, 65-10, 70-90, 80-90. For the carotenoid pigments the gradient was: [Time (min)-A (%)] 0-85, 5-85, 15-80, 20-80, 20-85, 30-85, 35-80, 40-80, 50-20, 55-20, 58-85, 60-85- 65-85.

RESULTS

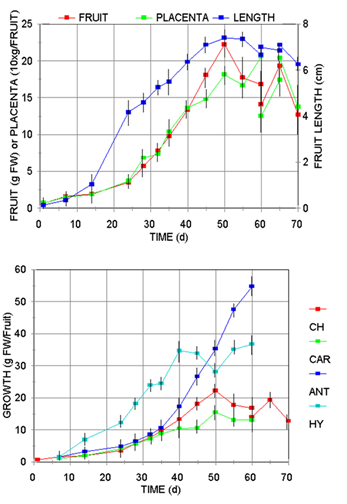

The pattern of fruit development for several Capsicum species, estimated by the elongation and fresh weight changes (Figure 1A), showed that all cultivars follow the typical sigmoidal growth curve with similar lag (0-8 d), exponential (15-30 d), stationary (50-60 d), and declination (60-70 d) phases regarding to length, weight and placental tissue. Although the maximum growth was variety-specific, all the species presented the shriveling phenomena at the beginning of the declination or senescence phase (60 d).

Fig. 1 A Profile of Capsicum annum var annum (Jalapeño) fruits development regarding to its fresh wight (FW), growth of its placental tissue (10xmg/Fuit), and its length pattern (cm); B, growth pattern of Capsicum frutescens (CAR, Carolina Cayenne), three Capsicum annuum var annuum cultivars (CH, Jalapeño chigol; ANT, Antler; HY, Hungarian Yellow).

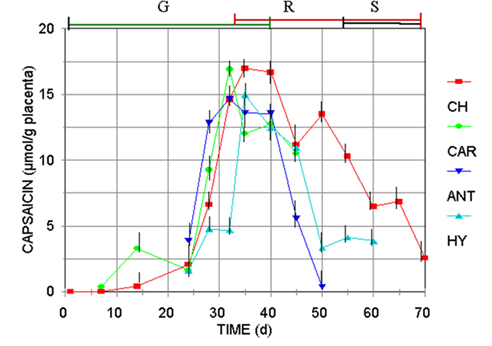

Fig. 2 Capsaicin accumulation pattern regarding the pigments production (color of the superior bars: G, green; R, red, S, senescence shriveling) for Capsicum frutescens (CAR, Carolina Cayenne), and three Capsicum annuum var annuum cultivars (CH, Jalapeño chigol; ANT, Antler; HY, Hungarian Yellow).

However, the content of capsaicinoids increased just in the period of direct relation with the fruit’s development, estimated by either their elongation, fresh wight, or evolution of the placental tissue (Figure 2), until the green color is exchange by the final carotenoid pigment, that is specific for each variety of Capsicum (red for CH, CAR, and ANT, and yellow for HY). Then, accumulation enter to a stationary phase, until fruits turn from the still harvestable mature green transition state (red, orange or yellow), to the shriveling senescence stage. Notice that the maximum content of capsaicinoids was reached during the stationary phase of growth, in the transition stage from green to the yellow, orange or red color. At this stage, the HPLC analysis for carotenoid pigments (Figure 3), confirmed that as the content of carotenoids increases, the content of capsaicinoids decreases. These results match with previous reports where the content of capsaicinoids showed a direct correlation with the maturation stage of green fruits and decreases during the transition state from green to the final-color of ripe fruits (Zamudio-Moreno et al., 2017, Castillo-Ruiz et al., 2017).

Fig. 3 HPLC chromatograms of carotenoid extracts from the pericarp of Capsicum frutescens var piquin, Capsicum chinense var Kahuil (habanero) and Capsicum annuum var Campana fruits at different stages of ripening.

It should be noticed that the harvest time for Capsicum fruits usually is accomplished during the last green stage or the transition from green to the pigmented final color, but always before the shriveling stage (about 50 d after anthesis).Although the declination rate of capsaicinoids was specific for each variety, the content of capsaicinoids and carotenoids showed a clear inverse relationship, observation that deserves further study to determine if chemical signals metabolic relationship between both types of compounds exists. Also, is important to consider that Capsicum fruits have been reported to be no-climacteric, and during the differentiation process of plant cell tissue the plastid genome is essentially stable, and the metabolic activity is restricted (Egea, et al. 2010). Perhaps for that reason, contrary to this work, declination of capsaicinoids content in old not-harvest fruits have not been studied on the bases that the biochemical metabolism of natural products in no-climacteric stops when the fruits are harvested and no catabolic reactions occurs.

CONCLUSIONS

Capsaicinoids reached the highest concentration during the color transition, from green to yellow, orange, or red pigment, depending on the variety of Capsicum. The end of capsaicinoids accumulation was clearly signaled by the start of the pigment's biosynthesis, suggesting this could be a metabolic switch acting as a signal for the ripening and senescence processes in Capsicum fruits, matching also with the reports that chili are no-climacteric fruits. When the accumulation of pigments and other carotenoids reaches its maximum, the fruit enters senescence and the content of capsaicinoids gradually decreases. These results suggest that the content of capsaicinoids could have a direct metabolic relationship with the elongation of the fruits and inversely with the biosynthesis of pigments. Furthermore, as Capsicum fruits have been reported to be no-climacteric fruits, declination of capsaicinoids content in postharvest fruits have not been reported.