Introduction

In December 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown origin were detected in the city of Wuhan-China, spreading with great ease.1,2 Subsequently, a virus was identified as the causative agent. It was denominated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), while the disease, COVID-19.3,4 On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the pandemic status due to this cause.5

Prolonged lockdown measures have been imposed on entire populations in order to slow down the spread of the virus and thus reduce the number of new SARS-CoV-2 infections, confirmed cases, and fatalities.6,7,8,9,10,11 These measures have included restrictions on outdoor activities and sports, as well as bans on social outings, gatherings, and festivals. As a consequence, citizens’ movements have been severely limited.12,13,14

The enforcement of these lockdown measures seems to have resulted in a significant decline in some of the main causes of trauma, such as sports and leisure trauma or car accidents, paralleled by a significant decline in facial trauma surgeries. It appears that this unprecedented phenomenon has not yet been enough documented in the literature.15,16,17

Community mitigation measures differ by geographic region and can be enacted at the town/city, county, state/province, or national level.8 Following the growing trend of virus spread a bold decision was taken by the Cuban government to enact a lockdown, which included closure of all the commercial activities and restricting the modes of transportation.18

Apart from mitigating the rapid and widespread transmission of this disease, it is unclear how changes in behavior related to these policies affect the incidence and etiology of maxillofacial fractures. This article aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 on the epidemiology of maxillofacial fractures surgically treated in a Cuban university hospital.

Methods

The present research involved a 4-year descriptive, comparative, retrospective and cross-sectional study in patients with maxillofacial fractures who were surgically treated (open reduction and internal fixation) in the Maxillofacial Surgery department of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes General University Hospital, Bayamo, Granma, Cuba. This hospital is responsible for the secondary care of patients from the capital and other six municipalities of the Granma province. However, patients from other municipalities of the province with neurosurgical issues are attended too because the unique Neurosurgery Department of the province is located at this hospital.

The first three cases (all Italian tourists) were identified on March, 2020. This date represents the start of the epidemic in Cuba.18 In this sense, patients treated between March 1 and December 31, 2020 (COVID-19 period) were identified and compared with those who had undergone surgery between the same date in the years 2017, 2018 and 2019 (non-pandemic period). The time periods were selected to capture patients who presented while measures of social distancing were and were not in effect and to provide a historical and temporal trend.

The study inclusion criteria were: a) patients of both sexes and all age groups; b) a history of an acute trauma episode; c) X-ray or computed tomography confirming the clinical diagnosis of fracture and evidencing its location and characteristics; d) signing of an informed consent by all patients, through which they agreed to the use of their medical data for scientific research. Patients with incomplete medical records or with unclear data were excluded. All the data were tabulated in a proforma specially designed for the study. During these four years, one hundred forty patients with maxillofacial fractures were surgically treated in our department. However, six cases had unclear/incomplete record and were excluded from the study.

Comparative analysis was performed for variables such as: number of trauma cases, sex, age at injury, residence (urban/rural), year, month, alcohol consumption at the time of trauma (yes/no), etiology (interpersonal violence, animal attacks, road traffic accidents (RTA), sport-related accidents, work-related accidents, home-related accidents, and complicated extractions), fractures types (mandible, zygomaticomaxillary complex, Le Fort I, Le Fort II, Le Fort III, panfacial, and nasoorbitoethmoidal), and number of fractures per patient. Alcohol consumption information collected was based on medical record.

A database was created using Microsoft Excel (2019 version for Windows). Frequencies and percentages of all the variables were obtained. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki on medical protocol. The Ethical Review Board of the hospital approved the study and provided permission to review the medical records of the patients.

Results

As shown in table 1, 134 patients underwent surgery, mainly in 2019 (n=41; 30.6%). The number of cases in the 2020 (n=25) was lower than the number in the 2017, 2018 and 2019 (n= 37.31, and 41, respectively). When comparing the percentage of patients with maxillofacial fractures surgically treated during the COVID-19 period to a non-pandemic period (mean value for the comparison period: March 1 to December 31 in the years 2017, 2018 and 2019), we found a reduction of 31.19% (table 1).

Table 1 Patient’s characteristics

| Characteristics | Categories | Non-pandemic period |

2020 (n=25) COVID-19 period |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (n=37) | 2018 (n=31) | 2019 (n=41) | |||

| Sex | Male | 33 (89.19) | 31 (100) | 36 (87.80) | 24 (96.00) |

| Female | 4 (10.81) | 0 | 5 (12.20) | 1 (4.00) | |

| Age (years) | < 20 | 3 (8.11) | 4 (12.90) | 0 | 2 (8.00) |

| 20 - 39 | 16 (43.24) | 14 (45.16) | 13 (31.71) | 7 (28.00) | |

| 40 - 59 | 15 (40.54) | 10 (32.26) | 25 (60.98) | 16 (64.00) | |

| ≥ 60 | 3 (8.11) | 3 (9.68) | 3 (7.32) | 0 | |

| Mean ± SD | 37.89 ± 14.51 | 35.71 ± 14.45 | 43.98 ± 12.71 | 41.16 ± 12.63 | |

| Residence | Rural | 13 (35.14) | 15 (48.39) | 25 (60.98) | 11 (44.00) |

| Urban | 24 (64.86) | 16 (51.61) | 16 (39.02) | 14 (56.00) | |

| Alcohol-related fractures | Yes | 19 (51.35) | 13 (41.94) | 19 (46.34) | 14 (56.00) |

| No | 18 (48.65) | 18 (58.06) | 22 (53.66) | 11 (44.00) | |

In all years, a greater proportion of injured patients were males compared with females, resulting in a general ratio of 12.4:1. The age of patients at the time of injury ranged from 13 to 69 years, with a mean age of 39.86 (±13.86) years. In 2017 and 2018, the commonest age group was 20-39, reporting 16 and 14 cases respectively, but in 2019 and 2020 was 40-59. There was a small increase in the number of alcohol-related fractures (56% in 2020 vs 46.34%, 41.94%, and 51.35% in 2019, 2018, and 2017, respectively) (table 1).

Interpersonal violence was found to be the paramount etiological factor for maxillofacial fractures during the comparison periods (2017-2019); however, road traffic accident prevailed in the 2020 (n=12; 48%). The commonest fracture type was zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures in all years. Most patients presented with more than two fractures, and the mean number of fractures per patient showed an increased in the 2020 compared to the 2017, 2018, and 2019 (mean=3.76 ± 2.09 in 2020; 2.22 ± 0.85 in 2017; 2.39 ± 0.95 in 2018, and 2.39 ± 0.95 in 2019) (table 2).

Table 2 Trauma’s characteristics

| Characteristics | Categories | Non-pandemic period |

2020 (n=25) COVID-19 period |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (n=37) | 2018 (n=31) | 2019 (n=41) | |||

| Etiology | Interpersonal violence | 15 (40.54) | 14 (45.16) | 21 (51.22) | 8 (32.00) |

| Animal attacks | 4 (10.81) | 2 (6.45) | 3 (7.32) | 0 | |

| Road traffic accidents | 12 (32.43) | 10 (32.26) | 10 (24.39) | 12 (48.00) | |

| Sport-related accidents | 2 (5.41) | 2 (6.45) | 0 | 0 | |

| Work-related accidents | 1 (2.70) | 2 (6.45) | 0 | 1 (4.00) | |

| Home-related accidents | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Falls | 2 (5.41) | 1 (3.23) | 7 (17.07) | 4 (16.00) | |

| Complicated extraction | 1 (2.70) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fracture types | Mandible | 18 (48.65) | 11 (35.48) | 16 (39.02) | 5 (20.00) |

| Zygomaticomaxillary complex | 18 (48.65) | 22 (70.97) | 23 (56.10) | 16 (64.00) | |

| Le Fort i | 2 (5.41) | 3 (9.68) | 0 | 2 (8.00) | |

| Le Fort ii | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.44) | 0 | |

| Le Fort iii | 1 (2.70) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Panfacial | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.88) | 2 (8.00) | |

| Nasoorbitoethmoidal | 1 (2.70) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Number of fractures per patient | 1 | 8 (21.62) | 6 (19.35) | 8 (19.51) | 2 (8.00) |

| 2 | 15 (40.54) | 11 (35.48) | 16 (39.02) | 5 (20.00) | |

| 3 | 12 (32.43) | 10 (32.26) | 9 (21.95) | 4 (16.00) | |

| 4 | 2 (5.41) | 4 (12.90) | 5 (12.20) | 9 (36.00) | |

| ≥5 | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.32) | 5 (20.00) | |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 2.22 ± 0.85 | 2.39 ± 0.95 | 2.56 ± 1.36 | 3.76 ± 2.09 | |

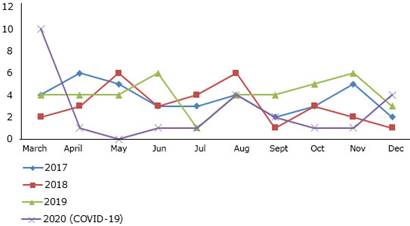

The detail by years and months is presented in figure 1. In the majority of the months of 2020, the number of patients was lower than the number in the rest of the years. In March 2020, a peak in incidence was noted (n=10) and was related with an RTA in which seven patients were affected.

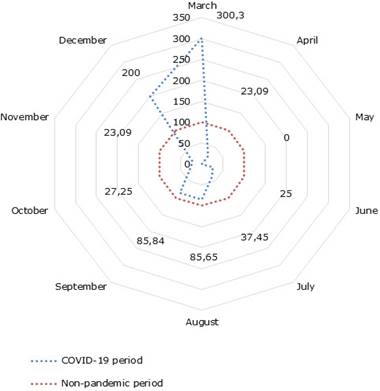

A decline in the incidence of maxillofacial fractures could be observed in all months, except March and December. April and November had equal decrease (76.91%, respectively) and a peak in reduction was noted in May (100%) (fig. 2).

Discussion

Maxillofacial trauma needs special attention due to their close proximity to and frequent involvement of vital organs, and for this reason, thorough evaluation of the maxillofacial region is mandatory during the primary stages of trauma care.19 As far as we know, there are still no Cuban published reports evaluating the effects of the lockdown on maxillofacial fracture patterns. In this study, we only included patients surgically treated in order to obtain a profile of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the epidemiology of severe maxillofacial fractures in this Cuban university hospital.

Our investigation found that the number of patients was lower during the COVID-19 pandemic while social distancing policies were in place. In other words, the most evident effect of the measures taken by the Cuban government was a reduction of 31.19% in the number of patients needing surgical treatment. This is similar to several reports in France,7 United States,8) India,12 United Kingdom,13 Italy16) and New Zealand.17 In South Africa, Moriss20 found the number of trauma cases reduced to 39% from 55% in 2018 and 51% in 2019 at the emergency department of an institute during the lockdown. Núñez21 observed a significant reduction in the number of emergency trauma visits on comparison with the four periods for emergency trauma visits during COVID-19 pandemic in Spain.

This was not unexpected because as the result of the pandemic and restrictions put in place, people are moving around less and staying at home more, making them less likely to sustain oral and maxillofacial injuries in the process.7,8,12,13,16,17,20,21

In our study, the sex distribution of maxillofacial fractures incidence is highly frequent in males and the overall male to female ratio was 12.4:1. Our finding was higher than to several previously conducted studies in United States (2.92:1)8) and Italy (2.59:1).16 These results might be due to that men tend to be more often involved in aggressive and conflict-ridden situations and are mostly involved in outdoor activities than women. Lesser incidence of maxillofacial fractures in females could be because of lesser reporting of injuries -due to either the sex-based neglect still prevalent in many rural areas or domestic abuse.22

Our research showed a reduction in patients aged 20-39 years, as well as ≥ 60 years during the COVID-19 period in comparison with previous years. Due to social distancing, young and active people have in fact experienced the most radical change in lifestyle. The consequent elimination of activities involving a risk of injury among these subjects has caused a reduction in the occurrence of trauma. The benefits of this effect have been less evident among the elderly population, who are more prone to accidental fractures within the home environment.16

Interestingly, this study revealed a 56% of alcoholic ingestion before the trauma during the 2020 (COVID-19 period). Ludwig et al8 in United States reported that there was a trend during the COVID-19 pandemic in this country of more individuals presenting with positive alcohol or toxicology screen results. Alcohol involved facial injuries may be more serious than non-alcohol related facial injuries as evident by higher proportion of patients requiring surgery. Facial injuries from alcohol-related trauma places a high burden on hospital resources. As alcohol-related maxillofacial trauma can be potentially preventable, educational programs and alcohol intervention strategies should be implemented to reduce such health hazards.23

There is a need to know the cause, severity and time distribution to set priorities for effective treatment and prevention of these injuries, which is related to the identification of possible direct or indirect risk factors for maxillofacial trauma.24 Our study revealed changes in the etiology patterns. During the comparison period (2017-2019), interpersonal violence was found to be the main etiological factor for maxillofacial fractures; however, RTA prevailed in the 2020. There is an opposite experience reported by Vishal et al12 in India. In this research, RTA was 85.44% in the control period which significantly decreased to 61.11% of total etiology during strict lockdown.

Concerning the fracture site, the ZMC bones were the most fractured followed by the mandible in all years. In a study conducted in United States by Ludwig et al,8 excluding skull base and cranial vault, this relation is similar. These results can be due to these bones prominence in the viscerocranium, which makes it susceptible to trauma. Also, the ZMC is biomechanically the lateral weight-bearing pillar of the midface, absorbing a large part of the kinetic energy of the wounding agents.25,26 Another aspect that should not be neglected is human defense instinct. People are frequently tempted to turn their head at the moment of the trauma, avoiding in this way frontal impact in the middle of the face.26,27

During the comparison period, the majority of the patients had two lines of fractures; however, in the 2020, this experienced a remarkable increase reaching a mean of 3.76 fractures per patient. Our finding was higher than to the study conducted in United States.8) The mentioned differences can be explained by the fact that the patterns of craniofacial fractures depend on a multitude of factors such as the type, direction, kinetic energy of the injuring agent or the position of the head at the time of the trauma, and especially on the fracture mechanism, leading to many possible variants of association of the fracture foci.27

The most marked reduction (100%) was recorded in May. In this month, Granma, the province where the hospital hosting this investigation is located, was seriously struck by the COVID-19 infection and this implied a more restrictive action to contain the contagion and to limit the spread of the virus. We hypothesized that this may be the reason why this month experienced such a decreased rate of patients with maxillofacial fractures needing surgical treatment.

Limitations of the study is that being retrospective, it may be subject to information bias due to inaccurate initial examination and incomplete or incorrect documentation. In order to minimize this shortcoming, only full medical records were selected. It would be interesting to study the number of patients that might have refused surgery out of fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2 during their hospitalization.

We concluded that COVID-19 impacted on the epidemiology maxillofacial fractures surgically treated in this Cuban university hospital with an 31.19% reduction compared with the three previous year.