Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

EduSol

versão On-line ISSN 1729-8091

EduSol vol.24 no.87 Guantánamo apr.-jun. 2024 Epub 15-Abr-2024

Original article

Educational policy and guidelines for migrant schoolchildren in Chile after the pandemic (2020-2023)

1Universidad San Sebastián. Chile

The present study aims to determine the response of the Chilean state in terms of ministerial policies and guidelines aimed at migrant schoolchildren, based on COVID-19. To this end, a documentary research of a corpus of ten issues published between 2020 and 2023 by the Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) was developed. From the thematic analysis, two categories were derived inductively that point to the areas of school education. The results revealed that only 3 guidelines refer directly to migrant students, but they are limited to providing general recommendations.

Key words: Educational policy; Migrants; School; Pandemic; Chile.

Introduction

Due to the pandemic, schools were forced to suspend their activities in person; this measure had an average duration of five months worldwide (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2020). As for the situation in Latin America, the suspension of classes reached an average of seven months, where two thirds of the schools have been totally or partially closed. Ninety-one percent of children continued to have access to education, but remotely, and about 114 million students were absent from Latin American classrooms, which is the highest figure recorded in the world (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2021). In Chile on March 16, 2020, schools closed completely and remained so "for more than 250 instructional days between 2020 and the first four-month period of 2022, which corresponds to almost 52 school weeks, or 1.4 school years (Izquierdo & Ugarte, 2023, p. 3). The educational crisis has been accentuated due to COVID-19, due to lack of access and the use of technologies by students, and this is deepened when it comes to migrant students, who constitute one of the most excluded groups (UNESCO, 2020). Therefore, after school closures, there are various effects on the teaching and learning process in students, both nationals and migrants, due to different needs, since developing online classes implies having access to the Internet as the main tool and the role played by an adult is fundamental (Voltarelli et al., 2021). According to the latest data systematized by the National Institute of Statistics and the National Migration Service, "as of December 2021, 20% of migrants in Chile are children and adolescents (NNA) of school age (Jesuit Migrant Service (SJM), 2023, p. 52). It is also important to note that migrant enrollment "has experienced a rapid increase in the last ten years in Chile, with 2022 being the year with the highest net enrollment and highest proportion of migrant enrollment to date" (SJM, 2023, p. 54).

Faced with this scenario, the Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) since 2016 has been generating a guiding corpus for educational communities that serve foreign students (Aguayo-Fernández et al., 2023; Joiko, 2023), these would prove insufficient in granting a satisfactory response due to the strong neoliberal component of the educational system straitjacketed in prescriptions and standards and due to the absence of teacher training and materials (Jiménez-Vargas, 2022). However, the studies by Aguayo-Fernández et al. (2023) and Joiko (2023) do not delve into the policies and orientations that emerged in the context of the pandemic and from there emerges the question that motivates the present analysis: What has been the response of the Chilean state in terms of policies and ministerial orientations aimed at migrant schoolchildren, since the COVID-19 pandemic? A public policy is a course of action or inaction by the government on public problems. They reflect not only the values that are most relevant to society, but also the conflict that may exist between values, so that policies demonstrate which of these various values is assigned the highest priority in making a particular decision (Kraft & Furlong, 2006). Regarding the state of public educational policy focused on foreign students in Chile, it has been pointed out through the figure of "eloquent silence" (Mora-Olate, 2018), due to an absence of it, which was remedied only at a declarative level in 2018 with the publication of the Policy 2028-2022 (MINEDUC, 2018), being unknown to date the results of its implementation. In 2017, the Provisional School Identifier (IPE) was implemented as a measure to improve the conditions of entry and permanence in school, however in the opinion of Poblete & Moraru (2020) of the bad with a public policy that ensures the right to education it would be necessary that this "also guides, orients and systematically supports the establishments in their work with this new type of student in terms of reception plans, initial leveling and adaptation "(p. 17).

During 2023 MINEDUC developed a process to update the National Policy for Foreign Students. In this regard, voices have emerged from the academic world suggesting an inclusive (Various Authors, 2023) and intercultural (Veloso, 2022) approach for this educational policy. As for the importance of the results constructed through the documentary research, it lies in its potential to challenge the actors of the school educational scene at different levels, especially those who formulate policies and guidelines in education, who aspire to sustain the inclusive educational approach in the context of migrant cultural diversity in Chile, challenged by the emergence of the global pandemic.

Migrant schoolchildren in a time of pandemic

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2020), calls pandemic to the global spread of a disease, which occurs when a new influenza virus emerges and spreads worldwide and the largest number of inhabitants do not have immunity to it. Specifically, in Chile the outbreak of coronavirus arrived in March 2020, which brought about a series of changes among which the mandatory confinement of the population stands out. This measure has had irremediable consequences for migrant families, due to the impediment of mothers, fathers to go out to work and achieve economic sustenance, where "health care becomes incompatible with subsistence, therefore, it is to be expected that situations of greater vulnerability are generated in migrant children and they are more impoverished as a result of the crisis" (Pavez et al., 2020, p. 259). At the same time, schools were forced to suspend school activities in person. In this regard, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2020) noted that this suspension occurred in several countries, 32 to be more precise, of which only 29 maintained this measure at the national level, except for Nicaragua. In turn, UNICEF (2021) indicates that this measure has had an average duration of five months worldwide. As for the situation in Latin America, the suspension of classes reached an average of seven months, where two thirds of the schools have been totally or partially closed. Ninety-one percent of children continued to have access to education, but remotely, and nearly 114 million students were absent from Latin American classrooms, which is the highest figure recorded in the world (UNICEF, 2021). Thus, throughout this pandemic, societies have been confronted with inequality, where the use of digital or technological tools has led to an even greater educational crisis due to COVID-19, due to lack of access and the use of technologies by students, which makes the educational system more complex for its participants, even more so when referring to the group of migrant students who are one of the most excluded groups (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2020).

As stated by Voltarelli et al. (2020), there are several effects on the teaching and learning process in students, both nationals and migrants, due to different needs after school closures, since developing online classes implies having access to the Internet as the main tool, and the role of an adult is fundamental. As documented by the SJM, access to technology and internet connection by families living in camps or "tomas" in Antofagasta, was null, therefore "it was found that with virtual classes different inequalities in access to education arose, including migrant and refugee population, especially the newcomers to Chile" (SJM, 2021, p. 25). In this regard, a study on the vulnerabilities experienced by migrant children in Santiago de Chile and in the northern part of the country (San Pedro de Atacama and Antofagasta) shows that during the suspension of on-site classes, adult caregivers had to prioritize economic survival, making it difficult for them to support them in their school work (Cárdenas et al., 2023). The latest Yearbook of Migration Statistics 2022 of the SJM (2023), highlights the increase in enrollment of foreign students during the pandemic (SJM, 2023), being and Colombian. However, the same report indicates the opposite situation in kindergartens where foreign enrollment in Board-dependent establishments of the total enrollment" (SJM, 2021, p. 24). A study conducted at this level of kindergarten education on the perception of Haitian families in the commune of Pedro Aguirre in Santiago de Chile regarding support in the teaching of their children in pandemic, reveals that kindergarten is a protective space, affectivity as an effective strategy despite language difficulties and technology management, but their culture of origin remains invisible (Sanchez et al., 2022).

Development

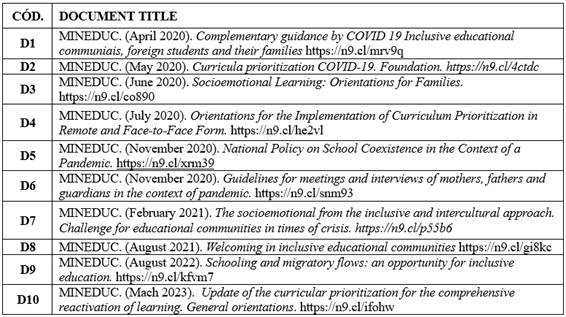

Through a qualitative documentary methodology, a corpus of 10 documents published between 2020 and 2023 by MINEDUC (Table 1) that refer to educational policies and guidelines was analyzed. The documents have been arranged in a table following the chronology of their publication and each one was assigned a letter D and a number; for example, D1.

The process of inclusion and selection of the documentary sources points to the documents that watch over the right to education of school-age children and youth who have migrated to Chile since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. As for the data collection techniques and instruments, it is important to point out that the documents were accessed through keywords ("educational inclusion"; "migration", "COVID-19") and downloaded from the search engine of the MINEDUC Digital Library's web platform. The corpus was subjected to a thematic analysis that allowed inductively raising two categories that point to the following areas of school education: 1) Sociemotional and Coexistence and 2) Curriculum and Learning. The results of the documentary analysis are presented below, organized according to the two inductive categories mentioned above.

1. Socioemotional and Coexistence Scope

Inclusive educational communities, foreign students and their families (D1), is a booklet that recognizes the need for recognition of this group within schools, under the premise of the protective role of the school and teachers, and therefore provides concrete indications for this purpose:

Spanish, whether or not they belong to the Social Household Registry, whether or not they live with their families or are in the process of family reunification, how long they have been in this migratory project since they left their city of origin; their living conditions and emotional support, access to technologies that facilitate their learning (D1, p. 2).

The National Policy on School Coexistence in the Context of Pandemic (D5), states that the educational community is a cultural space that is built and transformed into a place of containment, from a project with common purposes, adhering to agreed rules, with shared responsibilities and duties, where inclusion, collaboration and dialogue prevail. The promotion of instances of social inclusion would allow the creation of scenarios where respect for diversity would be a reality shared by the agents that make up the educational communities, achieving safe spaces for meeting and participation.

Socioemotional Learning: Guidelines for Families (D3) is a document published in June of the first year of the pandemic and recognizes the resounding change in the daily routines at home, since parents were forced to assume a pedagogical role during the confinement where the option to give continuity to the instructional process was remote classes. Notwithstanding the figures indicated above regarding the increase in foreign enrollment, these guidelines do not refer to immigrant families and their precarious conditions, which make impracticable issues such as this: "invite the student to prepare together the space for work (yours) and for study (the child's), that is, a quiet, orderly place, with materials available" (p. 8).

Guidelines for meetings and interviews of mothers, fathers and guardians in the context of pandemic (D6), published in November of the first year of confinement, highlights the importance of this space as "a valuable tool, which aims to know and cooperate in the development and integral formation of the students" (p. The words "migrant" or "foreigner" do not appear in this document, which provides general guidelines, such as the precautions to be taken into account when conducting the survey telematically, the schedules to be followed and the relevance of conducting interviews to address specific situations of each student.

In Lo socioemocional desde un enfoque inclusivo e intercultural. Challenge for educational communities in times of crisis (D7) recognizes cultural diversity as a pre-existing condition in the school and declares the inclusive and intercultural approach as the relevant foundation for the school to fulfill its ethical imperative to "continue advancing in an effective inclusion where no one is left behind" (p. 7). Following the idea of "challenge" in the subtitle of this guidance document, it assumes the pandemic in these terms: because "it offers us circumstances, examples and situations that allow us to put into practice these fundamentals for the sake of a comprehensive education under an inclusive approach that respects and values diversity" (p. 11). In the logic of the protective role that is recognized in the school, this document provides general guidelines to educational communities, emphasizes the importance of communication, mutual care and prioritizing the emotional state of its members more than academic leveling; however, it does not refer specifically to what would be the socioemotional practices regarding inclusion with migrant students and their families in the COVID-19 context. Moreover, the words "migrant" or "foreigner" do not appear in the document either, despite expressing that beyond the laws "if the subjectivity of the actors is not considered, inclusive education and the consequent valuation of cultural diversity cannot be achieved" (p. 12). In Welcoming in inclusive educational communities (D8) it is recognized that in times of health emergency there are students who need more support and special attention, as is the case of the migrant population, where their educational trajectories have been affected and also the processes of welcoming in schools. The emergency "makes us look at flexibility, adaptation and innovation even more centrally, as they become our most precious resources" (p.21). The concept of reception promoted by this ministerial orientation alludes rather to a process of accompaniment where "it is necessary to contemplate affirmative actions that open spaces of awareness, involving the whole community in the reception and accompaniment throughout the year of the student and his family" (p. 4).

When observing quantitatively the evolution in published orientations, 6 of them correspond to the area 1 of coexistence and socioemotional, a predominance coherent with the emphasis that the Chilean Ministry of Education has been declaring since the confinement and opening of schools. The prevailing idea of school that is reiterated in this first group of documents is to constitute a place of containment and a protective role, where cultural diversity is respected; a concept that is transversal to these documents and that seems to contain all the diversities of the educational space, since it is observed that only in two of the documents there is a direct reference to migrant cultural diversity through the denominations "foreign students and their families" (D1) and "migrant population" (D8). In these two documents, the containment and protection for foreign students in pandemic refers mainly to the recognition (saying that they exist) and the reception process, where in D1 it refers to the initial moment of the process, i.e., their entry into the school. In D8, an advance from the ministerial point of view is already observed in that the reception is more accurately proposed as a process of accompaniment beyond the arrival at school, but rather throughout the school year.

2. Curriculum and Learning Area

The suspension of face-to-face classes caused by the pandemic has not only had an impact on the educational process of all students in schools, but has also brought into discussion the density of the school curriculum in Chile, based on the measure adopted by the Ministry of Education in May 2020, which it called curricular prioritization. In the document Priorización curricular. Fundamentación (D2), curricular prioritization is proposed as a support to address diversity, taking importance Decree 83/2015, since "its purpose is to establish regulations for curricular adaptation in the context of inclusive education" (p. 4). It talks about the diversity present in the Chilean educational system in a general way, but in a broad sense, because it does not allude to migrant students specifically. The prioritization or transitional curriculum, from the principles of security, flexibility and equity, is conceived as a measure, a support tool for educational establishments that seeks to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the educational environment, reducing the contents proposed in the national curriculum. In July 2020, the document Orientations for the implementation of curricular prioritization (D4) was published, which indicates the levels of prioritization by school grade projected to the year 2021 and a series of recommendations for the implementation of learning objectives and their evaluation and different ways of organizing the curriculum either in remote or face-to-face modality, but it does not mention any indication for foreign students.

Zurita (2021) points out that this prioritization tries to give an answer on what knowledge, skills and attitudes proposed by MINEDUC would be feasible to execute during the current context, therefore, it has been designed by the latent need to make curricular decisions that respond to the pandemic context, in order to avoid an extensive and challenging load. Although this curricular prioritization was intended to recover and reinforce fundamental learning, in order to resume the curriculum in 2022, its validity was extended to 2025.

However, Jiménez and Valdés (2020) state that prioritizations in a pandemic state should not be focused on curricular coverage; on the contrary, they should be in terms of food coverage, health and emotional support, given that teachers have had to place greater emphasis on family contexts and their basic needs. However, this is correct in the first moment of confinement, but in the corpus analyzed, in terms of precise guidelines for action, a pedagogical emphasis for the case of migrant students during the pandemic remains silent. In this regard, Pavez et al. (2020), in coherence with the evidence built in this research, warn about the little attention paid by the State, through the following questions:

Why is there no specific measure for migrant children among the MINEDUC support during the COVID-19 pandemic? Has the official delivery of computers been a priority for migrant children? Is the "I learn online" platform available in the languages of origin of the migrant children population, does it have the possibility of online translation, does the content have intercultural relevance?" (p. 261).

As an element of context, it is necessary to point out that between March and April 2021, educational establishments voluntarily submitted the Comprehensive Learning Diagnosis (DIA), promoted by MINEDUC with the objective of monitoring the learning of students during the year 2020 in the Socioemotional Area and the Academic Area. The results were not very encouraging. For example, students did not achieve 60% of the expected learning with the curricular prioritization; that is why the educational authorities of the time described this situation as an "educational earthquake". As the report of the results is only received by the schools, the Education Quality Agency does not issue census results, which would allow monitoring (Izquierdo & Ugarte, 2023) of the performance of migrant students. On the occasion of this study, we requested, via the Transparency Law, the results at the national level and by region for this group, but we were not allowed access.

In August 2022, the working document Schooling and migratory flows: an opportunity for inclusive education (D9) was published. Its author, Valeska Madriaga Flores, proposes, in relation to educational policies, the recognition of cultural diversity as an ethical imperative and for this "it is essential that educational policy considers the approaches of inclusion and interculturality that give educational management an integral view, capable of guaranteeing meaningful learning and promoting healthy coexistence in difference" (D9, p. 3). It aspires to motivate reflection in teaching and management teams to "channel the improvement of pedagogical strategies and learning" under the premise of the right to education under equal conditions. However, it is not clear to whom this working document is finally addressed, because in the legal page its title says: "Schooling and migratory flows: an opportunity for inclusive education for personnel and officials of the Ministry of Education" and in its introduction: "This working and training document for the professional teams of the educational system" (p. 3). Regardless of the above and the purposes it sets out, this document develops aspects of the "must be" from the inclusive education approach, provides an overview of foreign enrollment, the corpus of guidelines published by MINEDUC referring to migrant students and alludes to the knots and learning gaps faced by this population; this aspect being the most noteworthy.

In March 2023, the Update of the curricular prioritization for the comprehensive reactivation of learning was published. General guidelines (D10), which reflects the experience of the massive return to school classrooms in 2022, which was marked by the impact of the pandemic in the dimensions of "is based on the principles of contextualization, teaching professionalism and integration of learning, valid until 2025, is part of the educational reactivation plan of MINEDUC Let's be a community, which aims to "promote a comprehensive and strategic response to the educational and socioemotional welfare needs that have emerged in school communities during the pandemic, articulating resources and policies in priority dimensions" (p. 1). Although this orientation does not directly refer to migrant students, the principles on which it is based pave the way for the inclusion of their knowledge, especially if one considers the objective of the principle of contextualization that promotes "decision-making by educational institutions and teaching teams regarding the prescribed curriculum, which makes it possible to give it meaning, enrich it or complement it based on the understanding of territorial and cultural elements and educational hallmarks embodied in the Educational Project" (D10, p. 4). In this second documentary group, composed of 4 pieces, as with the previous group, the general concept of diversity seems to contain migration. As a difference with the socioemotional area, the inclusive and intercultural approach does not seem to be relevant in the first moment of the curricular prioritization in 2020 (D2), but an approach from 2022 in the context of its updating for the comprehensive educational reactivation is glimpsed, if its principles of contextualization, teaching professionalism and integration of learning are considered. Only document 9 refers to the schooling of migrant students, conceiving it as an opportunity for the development of inclusive education. In sum, despite the fact that foreign enrollment experienced an increase during the pandemic and its presence in all regions of Chile, only 3 guidelines (2 in the socioemotional area) refer directly to migrant students, but are limited to providing only general recommendations. Therefore, the findings are in line with the results of a study of the same nature by Jiménez et al. (2017) developed prior to the pandemic, coinciding with the latter in the recognition of the existence in Chile of a broad corpus of potential usefulness "so that schools can improve their processes and/or reception plans, but which can easily fail to meet their objective due to the lack of more specific and contextualized guidelines, or due to the lack of support instances" (p. 114).

Conclusions

Although we share the idea of valuing the potential usefulness of a corpus such as the one studied to guide the work of educational communities with migrant students, however, despite the progressive increase in their school enrollment, the educational response of this set of educational guidelines published since the pandemic has been vague. This calls into question the inclusive and intercultural approach that is stated especially in the corpus of the Socioemotional and Coexistence area 1, where there is little reference, for example, to the situations of racism and xenophobia that migrant students have been exposed to during the pandemic. Therefore, there is an inconsistency with the premise that predominates in the total corpus studied about the school as a place of containment and its role of care for the migrant case.

This unspecific and decontextualized educational response was also observed in area 2 of the Curriculum and Learning, since this group is absent in the curricular prioritizations issued by MINEDUC. In summary, the focus of educational policies and orientations in Chile, approach migration from a functional integration and intercultural approach, this is exacerbated by the pandemic condition, because in the corpus analyzed, migrant students are not named and when it is the case, in a low proportion, or only tangentially through the broad concept of diversity. These forms of naming/not naming lead to the conclusion that rhetoric of silence prevails, which tends rather to the invisibilization of migrant students and which was exacerbated in pandemic times.

A worrisome example of this invisibilization is the absence of census data on the learning and socioemotional situation of this group. Although it is noteworthy that the MINEDUC will implement from 2021 an evaluation and monitoring system such as the DIA, which does not pursue a punitive purpose, but rather an improvement that allows educational establishments to know the progress and setbacks in areas as relevant as Reading, Mathematics and socioemotional, it is disconcerting that as a country and academic community it is not possible to access the census results referred to foreign students, via the Transparency Law. This invisibilization, which is more an exercise in assimilation, contrary to the inclusive and intercultural approach prevailing in the corpus in question, prevents us from knowing the needs of this group and, more importantly, hinders the collaborative design of inclusive educational responses, with the participation of academia, the State and the educational communities, considering territorial relevance.

One of the limitations of the findings of this documentary study is that they are insufficient to affirm that the premise that predominates in the total corpus studied about the school as a place of containment and its role of care has not been fulfilled, because it has rather been the teaching staff, who, in continuity with their situation before the pandemic outbreak, have found themselves in the even more urgent need to implement self-managed strategies, falling in their hands the responsibility of taking care of each of the diverse realities of their students and safeguarding their right to education, at the cost of suffering a great labor burden. With regard to the projections of the study, it is expected that new research will emerge that seeks to analyze the new educational policy for migrant students, and it is also hoped that studies will be generated to evaluate the descent of these documentary bodies in the school communities, from the voices of their protagonists: teachers, students and families.1

Referencias bibliográficas

Aguayo-Fernández, F., Díaz-Vargas, C., Moraga Henríquez, P. & Mora-Olate, M. L. (2023). Migración en Chile e inclusión educativa: un estudio documental (1980-2021). Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 21(2), 1-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.21.2.5447 [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. E., Olaya Grau-Rengifo, M., Alamo, N., Bernales, M., López, E., Donoso, B., Veas, A. & Grau-Rengifo, M. F. (2023). Dificultades y vulnerabilidades de la niñez migrante durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 21(3), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.21.3.5902 [ Links ]

Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF). (2020) Los efectos del COVID-19, una oportunidad para reafirmar la centralidad de los derechos humanos de las personas migrantes en el desarrollo sostenible. Informe del Primer Diálogo virtual. https://n9.cl/n1qz8 [ Links ]

Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF). (2021). 114 millones de estudiantes ausentes de las aulas de América Latina y el Caribe, El mayor número de niños fuera del aula en el mundo. https://n9.cl/9z3du [ Links ]

Izquierdo, S. & Ugarte, G. (2023). Crisis educacional escolar pospandemia. Centro de Estudios Públicos. Edición Digital N°641, enero. https://n9.cl/n8hqb [ Links ]

Jiménez, F., Aguilera, M., Valdés, R. & Hernández, M. (2017). Migración y escuela: Análisis documental en torno a la incorporación de inmigrantes al sistema educativo chileno. Psicoperspectivas, 16(1), 105-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-vol16-issue1-fulltext-940 [ Links ]

Jiménez, F. & Valdés, R. (2020). Las dimensiones no reconocidas del quehacer educativo en tiempos de pandemia: el cuidado y la protección de las minorías extranjeras en riesgo de exclusión. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(3), 1-8. https://n9.cl/xmevv [ Links ]

Jiménez-Vargas, F. (2022). Políticas educativas y migración. Lecciones en contextos de neoliberalismo avanzado. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 15, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m15.peml [ Links ]

Joiko, S. (2023). Construcción de subjetividades fronterizas de la niñez por las políticas educativas chilenas en contextos de migración. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 31(64), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.31.7671 [ Links ]

Kraft, M. & Furlong, S. (2006). Public Policy: Politics, Analysis and Alternatives, 2nd ed., CQ Press, Washington DC. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación de Chile (MINEDUC). (2018). Política nacional de estudiantes extranjeros 2018-2022. https://n9.cl/zgx8y [ Links ]

Mora-Olate, M. L. (2018). Política educativa para migrantes en Chile: un silencio elocuente. Polis, 17(49), 231-257. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682018000100231 [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO). (2020). Planeamiento de políticas de TIC para contextos de emergencia. https://n9.cl/xwbdr [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). (2020) Información básica sobre la COVID-19 https://www.who.int/es/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19 [ Links ]

Pavez, I., Poblete, D. & Galaz, C. (2020). Infancia migrante y pandemia en Chile: inquietudes y desafíos.Sociedad e Infancias, 4, 259-262. https://doi.org/10.5209/soci.69619 [ Links ]

Poblete, R. & Moraru, M. (2020). Avances y retrocesos en políticas educativas dirigidas a la población migrante en Chile: El caso del “identificador provisorio escolar.” Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 28(184), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.5074 [ Links ]

Sánchez, J., Moreno, I., Muñoz, X. & Palma, B. (2022). Percepciones de familias migrantes haitianas sobre apoyos dados en la enseñanza de sus hijos e hijas en contexto de pandemia. Revista Contextos, 50, 117-131. https://n9.cl/7mlsk [ Links ]

Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes (SJM). (2021). Migración en Chile. Anuario 2020. Medidas Migratorias, vulnerabilidad y oportunidades en un año de pandemia (N°2). https://n9.cl/dgfhh [ Links ]

Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes (SJM). (2023). Anuario de estadísticas migratorias: Movilidad Humana en Chile: ¿Cómo avanzamos hacia una migración ordenada, segura y regular? https://n9.cl/alhe [ Links ]

Varios autores (2023, julio 16). Una política nacional inclusiva para los estudiantes extranjeros. CIPER. https://n9.cl/wpfuq [ Links ]

Veloso, B. A. (2022). Avances y desafíos para una política de inclusión de estudiantes migrantes con perspectiva intercultural. (Tesis para optar al grado de Magíster en Gestión y Políticas Públicas). Universidad de Chile. https://n9.cl/od1pv [ Links ]

Voltarelli, M., Pavez, I. & Derby, J. (2020). Niñez migrante y pandemia: la crisis desde Latinoamérica.Linhas Críticas,26, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc.v26.2020.36298 [ Links ]

Zurita, F. (2021). Políticas educacionales escolares durante la pandemia COVID-19: el caso de Chile. En La Educación en tiempos de confinamiento: Perspectivas de lo Pedagógico (pp. 17-36). Fondo Editorial UMCE- Ariadna Ediciones. https://n9.cl/l0k9d [ Links ]

Received: September 06, 2023; Revised: November 20, 2023; Accepted: January 09, 2024

texto em

texto em