Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

EduSol

versão On-line ISSN 1729-8091

EduSol vol.22 no.78 Guantánamo jan.-mar. 2022 Epub 11-Jan-2022

Articles

Challenges of the inclusive education and school equality at educational Peruvian institutions

1Universidad Cesar Vallejo. Perú.

Building inclusive societies that leave no one behind and include all their members is an ethical obligation. The development of inclusive education models guarantees equal opportunities in one of the most critical stages of development. The purpose is to describe the challenges of inclusive education and school equality in Peruvian educational institutions. The highest level was found in the areas of interdisciplinary work and comprehensive education, curricular and institutional aspects. Deficiencies were found in the areas of implementation of accessibility, development of reasonable accommodations and participation of the learning community.

Key words: Disability; Education; School; Inclusion; Integration; Special Educational Needs

Introduction

Inclusive education is a fundamental human right for all students and enables the realization of other rights, involving the transformation of culture, policy and practice in all educational settings, whether formal or non-formal, to accommodate the different needs and identities of each learner. This is coupled with a commitment to removing barriers that hinder this possibility while also including strengthening the capacity of the education system to reach all learners, focusing on the full and effective participation, access, attendance and achievement of all learners, especially those who are excluded or at risk of marginalization for a variety of reasons, thus inclusion includes access and progression in high quality formal and non-formal education without discrimination (United Nations, 2006).

Inclusive education is considered the most effective strategy for combating discriminatory attitudes, guided by the idea that the school system should actively adapt to the individual circumstances of children so that they can reach their full potential. From a sociological perspective, it should be noted that the ambition to adapt the education system to the needs of all children is in line with the understanding of the close link between disability and the social environment (Michailakis and Reich, 2009).

In Peru, there are clear differences in access to education for people with disabilities compared to the rest of society. For example, 7.4% of adults with disabilities have not received any formal education, compared to only 1.3% of the rest of the population. On the other hand, 23.4% have incomplete primary education compared to 11.3% of people without disabilities (Senadis, 2015).

This is how, various efforts to develop Models focused on inclusion in education have sought to increase the impact of policies aimed at expanding access and permanence of the poorest groups in secondary and higher education, and to effectively address the social segmentation of school environments and educational outcomes. However, analysis by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) points out that "school-specific support models, while effective, are not sufficient to reduce inequalities, which are more structural in nature and require a new systemic approach" (OECD, 2004).

The purpose of this paper is to describe the challenges of inclusive education and school equality in Peruvian educational institutions. The highest level was found in the areas of interdisciplinary work and comprehensive education, curricular and institutional aspects. Deficiencies were found in the areas of accessibility implementation, development of reasonable accommodations and participation of the learning community.

Development

A qualitative study by López (2014) pointed out that this educational policy, as well as its school and pedagogical practices, contrary to its intentions, create obstacles to inclusion, as they tend to individualize, segregate and lose students' participation.

On the other hand, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations, 2006) marks a profound paradigm shift in which disability is considered a human rights issue and highlights the role of the environment and society in facilitating or limiting the participation of persons with disabilities.

These barriers include, but are not limited to, lack of political will, knowledge and capacity, including teachers, to implement inclusive education, inadequate funding mechanisms and/or legal standards or redress mechanisms in situations where the rights of persons with disabilities have been violated (United Nations, 2016).

This Convention fills a gap in international human rights standards and details in its articles the rights of persons with disabilities, which include civil and political rights, as well as the rights to accessibility, participation, inclusion, education, health, work and social protection, and goes beyond the concept of special educational needs of persons with disabilities (United Nations, 2006).

Regarding education, Article 24 states that "States Parties shall recognize the right of persons with disabilities to education. In order to realize this right without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity, States Parties shall ensure an inclusive education system at all levels, as well as lifelong learning." (p.14)

In this way, the requirements and standards of inclusive education as a fundamental element of public policy are clearly expressed and become an obligation for States. Creating inclusive schools means removing barriers to learning and participation for all students. This includes creating an inclusive culture, developing inclusive policies and practices (Booth and Ainscow, 2000). Without sparing that educational inclusion is understood as a set of processes aimed at removing or minimizing barriers that limit the learning and participation of students, especially for those groups of students who may be at risk of marginalization, exclusion or school failure (Echeita and Ainscow, 2011), which makes it a key tool for educational development in Peru and around the world to understand the key aspects of inclusion in education, some of which have explored the views of professionals and students in relation to the inclusion of students with disabilities.

Among their results, it is stated that "some of the factors that influence the lack of attention are: teachers' motivation, school and parents' demands, and the lack of evaluation of the project by the institution (...)" (Arias et al., 2005, p.51). On the one hand, some authors defend its positive effects, while others highlight the many complexities in its implementation or the lack of evidence on its application.

Barriers and facilitators of inclusion can be found in the elements and structures of the system: in schools, in the community, and in local and national policies (Booth and Ainscow, 2000; Guerra, 2006).

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) states that to fulfill access to free, quality primary and secondary education, the education system must include the following four interrelated features:

Availability of places,

Accessibility,

Acceptability of the form and content of education for all, and.

Adaptability of the educational process (United Nations, 2016).

Therefore, in an environment based on the principles of inclusive education, all individuals in the school community, regardless of their background, gender, physical or intellectual ability, religion, socio-economic status or other similar factors, should be included, respected and treated fairly. Diversity becomes a value that enables the development of a safe, welcoming and accepting school community (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010).

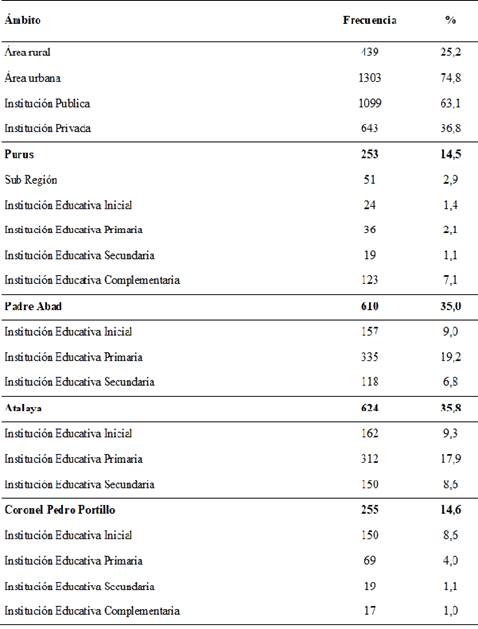

A total of 1,742 valid questionnaires were received for the development of the work. Based on the sociodemographic variables analyzed, we found that schools have been implementing the school equity model for an average of eight years. The distribution by region, macro-region, location zone and administrative unit is shown in Table 1.

It should be noted that more than 60% of the responses obtained correspond to schools of municipal administrations. The professionals most associated with the school equity model to meet the needs of students with disabilities are, in descending order, psychologists 94.0%, special educators 93.7%, speech therapists 78.0% and psychopedagogues 66.1%.

The implementation of supports and aids for children with sensory disabilities is less than 20%. In particular, schools do not have reading material in Braille, audio books or staff trained in sign language (8%). In general, there are no significant differences between the macro areas, except in the provision of educational material to meet the needs of students with disabilities (p = 0.021), with the Desert macro area having a lower percentage of provision than the national one and the Productive and Export macro area having a higher percentage than the national one.

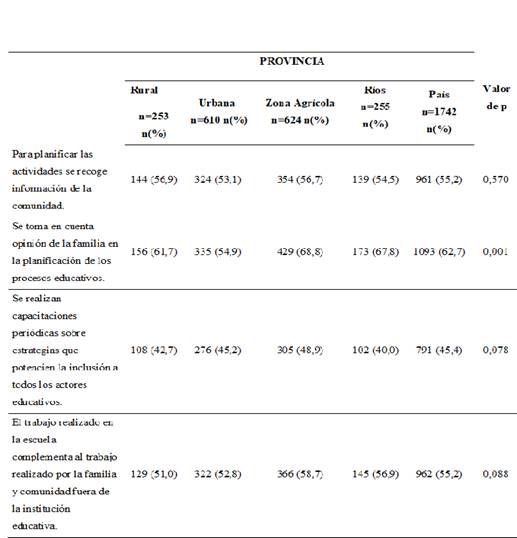

In general, the SIP (Progress Report) coordinators report that activities are carried out in an interdisciplinary manner and develop joint work between full professors and support staff (86%). There are significant differences with respect to the national trend in terms of collaboration in the various teaching activities, the meeting of SIP specialists and the development of teaching planning and organization between professors and SIP specialists, with the central metropolitan area showing a lower concordance with respect to the national level, while the productive exporting macro-area is above the national average. Regarding curricular aspects of the curriculum, most of the centers (more than 70%) state that they have additional accommodations and supports in assessment and teaching and learning for students with disabilities. (See Table 2).

Regarding aspects related to the participation of the educational community, the low participation of students in decision-making spaces such as student centers stands out. Less than 50% of the educational institutions state that they are considered in their directives and decisions. Regarding the participation of the family and the extramural community, in half of the educational institutions they are considered in the work carried out. It is noteworthy that less than 50% of the educational institutions, in all the macro-zones, declare that they carry out periodic training on strategies that promote inclusion of all the educational actors.

Significant differences are only identified among the macro-zones in the involvement of the family in the planning of educational processes, being lower at the national level (97.1%) and in the desert macro-zone (93.7%), and higher in the macro-zone of the lakes and southern channels (99.2%).

Taking into account the above results, the main findings in the dimensions of implementation of the School Equality Model in Peru were higher levels of implementation of interdisciplinary work areas and comprehensive training. Nearly 90 % of school coordinators indicate that activities are carried out in an interdisciplinary manner, while, from the curricular aspects, more than 70 % state that they have additional adaptations and support in the aspects of evaluation and teaching and learning for students with disabilities.

Table 1: Distribution of educational institutions that participated in the study by region, area and administrative unit (n=1742).

Source: Self elaboration.

On the other hand, the implementation of accessibility and the development of reasonable accommodations is one of the weakest areas. For example, support and assistance for children with sensory impairments is less than 20%, especially aids such as Braille readers, audio books or staff trained in sign language (8%).

Table 2: Curricular aspects of the School Equality Model. Responses yes and always/almost always by province (n=1742)

Source: self elaboration

This suggests that the schools did not have even the minimum resources for inclusive access to books or teaching materials. This situation can be attributed to the fact that most of the included students with learning disabilities, since according to current regulations, the predominant personnel are psychologists who must carry out the evaluation and identification of special educational needs. These characteristics of the personnel involved and the presence or absence of reasonable accommodations indicate that schools are ill-prepared to receive students with sensory or physical disabilities. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the different components needed to address the challenges associated with school inclusion through the assessment of specific areas (Guerra, 2006; Marfán, 2013) to ensure the effectiveness of inclusion strategies for children with disabilities.

At the same time, teacher professional development appears to be insufficient in terms of supporting social inclusion training activities for professionals. In this case, it can be understood that teacher professional development is not a strength.

These results coincide with those obtained by Arias et al. (2005) in a local national context, where teachers recognize teacher training, greater participation and involvement of families and, finally, a professional team trained for the different learning periods of children with Special Educational Needs as challenges. Regarding the aspects related to the participation of the learning community, the scarce participation of students in decision-making spaces such as student centers and the scarce participation of families and the extracurricular community stand out, which should be one of the most important challenges to be faced by the school, in relation to families and the different members of the community, in order to make the school a shared project with a greater degree of equity.

This condition is key to building a society of equals that values differences. Regarding the level of inclusion in general, this model is evaluated favorably in most cases. However, questions that seek to identify more specific aspects and objectives of the facility itself, such as accessibility and reasonable accommodation, reveal the need for substantial improvements beyond the will to be an inclusive facility. In fact, accessibility and universal design is the least developed area, with almost 60% stating that the furniture would not adapt to the workplace of a student with a disability. This is of concern because the most significant difficulties that children with disabilities experience in school are related to learning aids, empathy with peers, and barriers in the students' physical environment.

Particularly striking is the presence of significant differences between macro-areas in:

Whether collaboration is encouraged in the various teaching activities involving students with disabilities;

Whether specialists and teachers participate in planning meetings and collaborate in the development of lesson plans;

Whether teachers and specialists plan and organize lessons together; and

Whether recommendations from support professionals are taken into account.

More studies are needed at the regional level to explain the differences found in the implementation of this national policy, since the differences in coverage between regions and between urban and rural areas, as seen in the report by Marfán (2013), are significant. A limitation of this study is that the survey was commissioned only from school coordinators. Although they are an important part of the school community, they represent only a part of the opinions of the actors in the educational process.

Another limitation of this study is related to the data collection technique, since this questionnaire does not allow us to draw a conclusion on the level of effective compliance by educational institutions in relation to what is described in both the technical guidelines and the guidelines established by UNESCO. An observational approach in the institutions would help to collect information that cannot be collected through instruments, along with variables that people do not perceive or do not report.

As a projection of this study, it is important to include other actors of the educational community to give a more complete and holistic view of the reality of school inclusion in Peru. This deepening can be achieved through the use of qualitative research, especially participatory and ethnographic methodologies, which allow for a more intense and valid collection of information on the school inclusion process, information that is not well developed in the literature and which is absolutely necessary. In addition, it is considered that future studies should standardize the methods of measuring the implementation of these models in order to be able to make comparisons in different regions: Latin America, Europe, Asia, etc., in order to develop collaborative inclusive education processes with valid and repeatable data collection.

The applicability of these results in the context of education can be analyzed from different perspectives. First, these results are useful for assessing the correct implementation of the equity model in schools for local and national control, monitoring and implementation agencies, which can support the contextual diagnosis and implementation process of their public policies. Advances in the evaluation of the impact of educational policies will make it possible to improve educational equity strategies and achieve inclusion in the classroom and in society.

This study confirms what Blanco and Duk (2011) pointed out in the sense that most countries accept the right to education in their laws and policies, but in practice it is observed that this right is not guaranteed equally to all individuals and social groups. A fair education system must not only guarantee equal access to different levels of education, but also democratize access to knowledge and respect the diverse identities of individuals so that everyone feels part of society and can participate on an equal footing.

Expanding opportunities for access to quality education for all and developing more inclusive schools that educate in and for diversity are two powerful tools for advancing towards more equitable and democratic societies in Latin America. This is a serious task because it implies profound changes not only in education systems but in society as a whole (Blanco and Duk, 2011).

Therefore, it can be stated that effective inclusion will be achieved if paradigms are changed, if it is considered that disability is not an innate attribute, but a social construction, because when we talk about disability, it refers to a relational category that manifests itself in the negative interaction between a set of contextual, attitudinal and environmental barriers with a person in any health situation that limit the full enjoyment of rights and autonomy of people.

With this conception of disability, the analysis in its educational dimension becomes more difficult, since disability can be understood as a limitation imposed on the subject by the environment, both the people and the space with which he or she interacts. It should be noted that in some countries, such as Ireland, an increasing number of students with disabilities are leaving regular schools to attend special schools. The main reason given is that mainstream schools are unable to meet their learning, social, emotional, behavioral, access and resource needs. The experience of inclusive education in Ireland is similar to that of countries still struggling to implement inclusive practices in the midst of socioeconomic and educational constraints (Kelly, 2014), as described in Peru.

Conclusiones

This research has provided relevant information on specific indicators linked to inclusive education standards. It can be concluded that the areas that require urgent work and care by the actors associated with the school equity model are, first of all, the availability of facilities and materials used, as well as the participation of students in curricular and extracurricular activities and the training and professional development of teachers and support staff.

Within the framework of the educational institution of the guidelines for the necessary reform of the educational system for students with disabilities, it can be concluded that there is still room for improvement in the area of inclusion in education, both in terms of providing objective conditions that guarantee the development of the potential of students with their environment, as well as in terms of subjective or social conditions that promote social inclusion.

This study provides an overview of the implementation of the educational inclusion model at the national level and reveals that there are many challenges to achieving inclusive education.

Referencias bibliográficas

Arias Nahuelpán, I; Arriagada Pérez, C; Gavia Herrera, L; Lillo Martínez, L y Yáñez González, N. (2005). Visión de la Igualdad de niños/as con NEE (Necesidades Educativas Especiales) desde la perspectiva de profesionales y alumnos/as (tesis de pregrado). Universidad de Chile. https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/106490 [ Links ]

Blanco, R. y Duk, C. (2011).Educación inclusiva en América Latina y el Caribe. Aula: Revista de Pedagogía de la Universidad de Salamanca, 17. Pág. 37-55. [ Links ]

Booth, T. y Ainscow, M. (2000). Índice de Inclusión. Desarrollando el Aprendizaje y la Participación en las escuelas. Inglaterra: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (CSIE). [ Links ]

Echeita, G. y Ainscow, M. (2011). La educación inclusiva como derecho. Marco de referencia y pautas de acción para el desarrollo de una revolución pendiente. II Congreso Iberoamericano sobre Síndrome de Down. Granada España. [ Links ]

Guerra, C. (2006).Proyectos de Igualdad escolar, factores que facilitan y obstaculizan su funcionamiento (tesis de pregrado). Universidad de Perú. Santiago http://www.tesis.uPerú.cl/tesis/uPerú/2006/ guerra_c/sources/guerra_c.pdf>. [ Links ]

Kelly, A. (2014): “Challenges in Implementing Inclusive Education in Ireland: Principal’s Views of the Reasons Students Aged 12+ Are Seeking Enrollment to Special Schools”. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11 (1) .Pág 68-81. [ Links ]

López, V. (2014). Barreras culturales para la Inclusión: políticas y prácticas de Igualdad en Perú. Revista de Educación, 363. Pág. 256-281. [ Links ]

Marfán, J. (2013). Análisis de la implementación de los Modelos de Igualdad escolar (PIE) en institucion educativas que han incorporado estudiantes con necesidades educativas especiales transitorias (NEET)<http://www.mineduc.cl/usuarios/edu.especial/doc/201402101719500.InformeEstudioImplementacionPIE2013.pdf> [ Links ]

Michailakis, D. y Reich, W. (2009). Dilemmas of inclusive education. ALTER, European Journal of Disability Research, 3 (1). Pág. 24-44. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación de Ontario(2010). The Ontario curriculum grades 1e8: Health and physical education, revised interim edition. Ottawa: The Queen’s Printer. [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas (2006). Convención de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad. <http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/documents/tccconvs.pdf> [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) (2004). Revisión de Políticas Nacionales de Educación. http://www7.uc.cl/webpuc/piloto/pdf/ informe_OECD.pdf [ Links ]

Received: March 18, 2021; Accepted: August 25, 2021

texto em

texto em