Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Universidad de La Habana

versión On-line ISSN 0253-9276

UH no.285 La Habana ene.-jun. 2018

Black Artists and Race in the U. S. and Cuba. Reflections after more than a half century of liberation and civil rights

Artistas negros y raza en EE. UU. y Cuba. Reflexiones después del medio siglo de la liberación y los derechos civiles

Colette Gaiter

University of Delaware, U. S.

RESUMEN

Contrastes y similitudes en la obra de algunos artistas afro-cubanos y afro-americanos que toman como motivo el tema raza para reflejar las diferencias que se manifiestan en la sociedad a la que pertenece. Artistas negros en ambos países toman la racialidad como tema, con diferente impacto social. En Cuba, las voces de los artistas parecen tener mayor correlación con la imagen política que la que la sociedad tiene de sí misma. Algunos artistas también se sienten cómodos comentando la situación de los Estados Unidos a través de su obra. Los trabajos de los artistas afro-cubanos que critican la sociedad estadounidense y su política parecen ser más favorablemente recibida internacionalmente que las protestas artísticas de los afro-americanos que tratan temas raciales. La visibilidad y volatilidad de las relaciones raciales en los Estados Unidos disminuyen irónica y efectivamente el impacto del arte que critica estas condiciones. Los artistas de la diáspora africana en ambos países utilizan las potencialidades del arte para aumentar la concientización y, en última instancia, realizar cambios sociales progresivos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Arte afro-cubano, arte afro-americano, exposición Queloides, Black Lives Matter, Bienal de La Habana, Alexis Esquivel, Hank Willis Thomas, Kara Walker, Alexandre Arrechea, artistas de la diáspora africana, Esfinge de Azúcar.

ABSTRACT

Contrasts and similarities between the work of some contemporary Afro-Cuban and African American artists reflect differences in each society's attitudes about art and race. Black artists in both countries take on race as subject matter, with different societal impact. In Cuba, the voices of artists seem to have more agency within the society's political self-image. Some artists are also comfortable commenting on the U. S. through their work. Works by Afro-Cuban artists that critique U. S. society and politics appear to be more favorably received internationally than protest art by African American artists that addresses racial issues. The visibility and volatility of race relations in the U. S. ironically and effectively diminishes the impact of art that critiques those conditions. Artists of the African diaspora in both countries utilize art's potential for raising awareness and ultimately effecting progressive societal changes.

KEYWORDS: Afro-Cuban art, African American art, Queloides exhibition, Black Lives Matter, Havana Biennial, Alexis Esquivel, Hank Willis Thomas, Kara Walker, Alexandre Arrechea, African diaspora artists, Sugar Sphinx.

Contemporary artists' works in the United States of America (U. S.) and Cuba reflect the nuanced way race is experienced in each country and offer insights that are often not expressed in other media. Even though Cuba and the U. S. have similar racial histories regarding slaves brought from Africa, perceptions and behavior about race and racism are different. These disparities are due to variables like the number of people of African descent in the two countries, assimilation into a white dominated society, and social and legal practices since the abolition of slavery. Looking at highly the visible works created by artists in these two countries offers opportunities to study the intersections of politics, race and art in two vastly different systems.

The work of several "superstar" artists in the U. S. and Cuba who are currently celebrated by the international art world exemplifies the differences in agency and influence on various audiences in each country. Afro-Cuban(1) artist Alexandre Arrechea won the Farber Prize for Cuban Art at the 2015 Havana Biennial. The Venice Biennale in the same year commissioned African American artist Kara Walker to direct and design sets and costumes for a new production of Vincenzo Bellini's 1831 Norma, a two-act tragic opera to a libretto by Felice Romani (La Biennale Di Venezia, 2015).(2) Both works fascinate and enlighten their audiences worldwide with thoughtful works that embody –rather than transcend– race.

In 2015 the topic of race was at the top of the news in the U. S. in 2015, following a year of protests surrounding several high profile deaths of unarmed black people at the hands of the police. In June of that year, a white man who said he "wanted to kill black people", murdered nine at bible study in their church in South Carolina. Nationwide discussion on how people of color are treated when suspected of criminal activity restarted after the death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager, was killed in 2012 by a white man on citizen patrol. Martin was walking home from a convenience store and presumed to be a criminal (Dahl, 2013).

In November of 2014, tens of thousands of people marched peacefully in 90 cities across the U. S. to protest that there was no indictment against the police officer who murdered an unarmed young black man, Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri, the previous August (Mccormack, 2014). The protests against a perceived lack of accountability from police departments spawned a media campaign called #BlackLivesMatter, started by three African American women activists: Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi (Milloy, 2015).

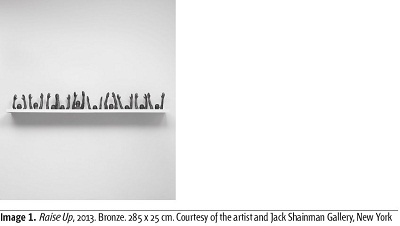

As racial tension escalated, the world again looked at the U. S. as a country with a big race problem. There has not been this much scrutiny on the topic of race since the mid twentieth century Civil Rights movement marches and widely reported police brutality. Many African American artists responded to the incidents, protests, and #BlackLivesMatter campaign in their work. A 2013 bronze sculpture by Hank Willis Thomas titled Raise Up, which references SouthAfrican workers subjected tonude searches, became an iconic image of black people with their hands up. Images of African Americans in the same pose proliferated on the Internet, signaling protest with no violent intentions (image 1). Students at Howard University, a historically black university in Washington D. C., helped this visual meme get wide publicity when they staged a 2014 protest on their campus and hundreds of students posed for a photograph with their hands held up in surrender.

To put these recent protests in historical perspective regarding racial progress in the U.S., it is important to take into account that the Civil Rights Act outlawing segregation passed through Congress and became law only in 1964. Before that landmark legislation, the U.S. had Jim Crow laws, which institutionalized and maintained segregation and discrimination against people of color. These laws meant that colored people had to use separate facilities for everything including housing, schools, hospitals and restrooms. They were also explicitly forbidden from many public and private businesses and institutions (Urofsky, 2015).

Even though there is progress in the struggle for racial equality, racial profiling -a common practice allowing police to behave in discriminatory ways toward black people, particularly young black men- is still a problem. According to the British newspaper The Guardian: "When adjusted to accurately reflect the U. S. population, the totals indicate that black people are being killed by police at more than twice the rate of white and Hispanic or Latino people. Black people killed by police were also significantly more likely to have been unarmed" (Laughland, Swaine and Lartey, 2015).

One hundred and fifty years past the end of slavery, the U. S. still struggles with racism. The country fought a brutal Civil War over slavery, finally ending the practice in 1865. The termination of slavery did not end racism, since creating a persistent myth that black people are inferior justified enslavement. Structural inequality -racism built into economic and social systems- perpetuated slavery.

The U. S. and Cuba share a legacy of white people importing Africans as slaves and the residual effects of that economic and social system. Just as the slave trade was essential to cotton production in the southern United States, African slave labor was essential to sugar production, which has been linked to the Cuban economy since the sixteenth century (Pérez-López, 1991).(3) Consequently, racial injustice is officially part of Cuba's own past enslavement under colonialism. Afro-Cubans have the international slave trade's oppressive racial legacy to reconcile -along with the rest of the African diaspora -in addition to participating in Cuba's revolution.

In the U. S. artists express whatever political beliefs they may have through their work, but their ideas and messages rarely reach mass audiences. Film and television characters have more social impact than visual artists. Artists are not considered to be important social commentators outside of specific small audiences. Conversations about important social issues like civil rights and race seem to be taken most seriously when they occur through commercial broadcast media and print disseminated by newscasters, academics, and public figures rather than by artists through popular culture.

In Cuba, popular culture can be the most available venue for certain discussions and people create "artistic public spheres" (Fenandes, 2006), allowing comment on sensitive issues. According to theorist Jürgen Habermas, the public sphere "mediates between society and state" (Habermas, Lennox and Lennox, 1974). In general, cultural theorists have not regarded public spheres created in socialist systems as viable because they believe that artistic public discourse should not be financially dependent on the state. They also maintain that cultural producers should be able to freely challenge economic and government policies. Sujata Fernandes, in her 2006 book Cuba Represent!: Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures, argues that in Cuba "[the state does not act] as a repressive centralized apparatus that enforces its dictates on citizens from the top down but as a permeable entity that both shapes and is constituted by the activities of various social actors" (Fernandez, 2006, p. 3). In the U. S., government arts subsidies are small in relation to total costs and have been shrinking for decades. The arts are mostly financed by private donations, often from large corporations.

The irony is that even though the arts in Cuba are state sponsored; the thoughts of visual artists, musicians and filmmakers about society, culture, and even politics receive a broader audience and are taken more seriously. For example, Cuban artist Tania Bruguera's attempt to stage a performance about free speech in Havana's Revolution Square in late December of 2014 became notorious or heroic, depending on the point of view -and to which it was well publicized. Because she did it shortly after U. S. President Obama ordered the restoration of full diplomatic relations with Cuba and the opening of an embassy in Havana for the first time in more than a half-century, her actions received international attention (Haupt and Binder, 2010). Art and politics have a more symbiotic relationship in Cuba than they do in the U. S.

Despite the embargo, Cuban cultural producers have remarkable knowledge and insights about globally dominant countries, particularly the United States. Most people in the U. S. know very little about Cuba because of an almost total news and media blackout about events on the island. Cuban artists can observe without being seen and create insightful work about their neighbors to the north.

Integration and Resistance in the Global Era, the 2009 10th Havana Biennial exhibition, projected Cuban and other global artists' perspectives to an international audience. The title refers to Cuba's efforts to interact with the Western world while resisting practices that are in ideological opposition to the revolutionary government, suggesting that Cuba and other marginalized countries will participate globally on their own terms, maintaining resistance to U. S. and Western capitalist domination (Weiss, 2011). However, the work of the Biennial artists represents the degree to which discussions of race are nuanced within this critique of globalization.

Afro-Cuban artist Alexandre Arrechea's works fluidly crosses over national, racial, and artistic genre boundaries. After living in Spain and the U. S., he projects his insights into the capitalist world through the multicultural perspective of cubanidad (Candelaria, 2004). As John Angeline wrote in ArtNexus magazine, in Arrechea's work, "formal concerns are not mutually exclusive with social issues, and that playfulness and wit can be subversive and meaningful" (Angeline, 2013).

For the 2009 Biennial Arrechea joined other Cuban artists in interrogating international institutions and practices that do not exist in Cuba. In terms of cultural practice, artists like Liset Castillo, Ramírez de Arellano, Velasco, and Arrechea work from a Cuban point of view that critiques Western capitalist culture in the present rather than relating to history or tradition. Their aesthetics, conceptual approaches, and contemporary materials and techniques position their work squarely in the current international art market.

Arrechea's clever and technically impeccable 2013 satirical architectural sculpturestitled "No Limits" on Park Avenue in New York City -one of the most expensive areas in Manhattan and the entire U. S.- were received as more amusing than confrontational by some arts writers in the U. S. (Knudsen, 2013). Perhaps a critique of capitalist icons would be disloyal or hypocritical if created by someone who grew up in the U. S. rather than the island that has endured more than a half century of economic embargo enforced by many of the same financial and business institutions lampooned in Arrechea's works. African American artists are most often expected to do work about race and their work on other topics gets little attention. Paradoxically, there is a concurrent thread of criticism about race being a perennial subject in work by African American artists. Arrechea has an advantage as an outsider to be taken seriously (or satirically) if he makes work on a subject as monumental as the physical icons that represent global economic domination.

Each large-scale steel and aluminum sculpture on the Park Avenue median represents an architectural icon such as the Chrysler Building (headquarters of the huge automobile manufacturer and New York City landmark), the former Citicorp Center (which housed global financial giant Citibank), the Empire State Building, and others. A model of the Citicorp Center, already asymmetrical with its slanted roofline, sits on top of a huge spinning toy top, which theoretically could spin, but never will. The physical imbalance becomes a metaphor for the global fiscal crisis that persisted for many years (MagnanMetz, 2013). New York's luxury Sherry Netherland Hotel is represented as bent into a red circle that resembles a creature eating its own head (Havana Cultural, 2009). These buildings were recontextualized in laughable impossible ways: the classically monolithic Seagram's building for example undulates upward in a serpentine fashion from a support as if it were a giant fire hose. The Citigroup building is perched somewhat fancifully upon a brightly colored children's spinning top (Angeline, 2013).

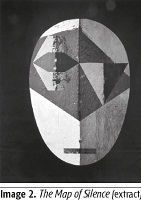

Alexandre Arrechea's exhibition in the 2015 Havana Biennial, The Map of Silence (image 2), shown at Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, moves away from the sleek industrial craftsmanship of his 2009 Havana Biennial work and 2013 Park Avenue No Limits installations. He uses photographs of heavily textured and deteriorating building surfaces to construct images that he says he hopes to become "a more recognizable face of neighborhood or areas" (Cuban Art News, 2015). Combining African masks and photographs of deteriorating buildings into tapestries connecting Cuba's past and present in a completely contemporary way. His comments on the exhibition are provocative and vague, but suggest a shifting of the silence he refers to. He said: "I'm focusing on silence as a context where we all behave differently. There is the silence for good causes and silence for wrong [...] the exhibition will be a map of multiple silences, where the masks are only one part of that silence that now starts to be revealed into a kind of noisy image" (Cuban Art News, 2015).

Arrechea's 2006 video installation, White Corner brings up race as a topic, although in an oblique way. His web site describes the piece this way:

Pared down to two adversaries, both played by the artist himself, one holds a machete, reflecting Alex's own history, with ancestors who fought in the Cuban War of Independence, and the other a baseball bat. They approach the edge of the corner, each waiting for the other to cast the first blow. As he says, the opponents are more like one another than different. They are motivated and paralyzed by pure fear (Zeitlyn, 2007).

This piece seems to communicate an understated message about racial stereotypes and their consequent limitations. The image of a "wild" black man with a weapon is a recognizable archetype representing fears about black men that were invented during slavery to make black men seem dangerous and threatening. Arrechea may be addressing the limited opportunities that black men had to elevate their status in his country, including fighting in the War of Independence, not long after being freed as slaves. The baseball bat, which is seen here as a weapon, can also represent baseball as a place of opportunity for Afro-Cuban men. This "savage" or "aggressive black man" representation of black men is a signifier recognizable across nations and cultures.

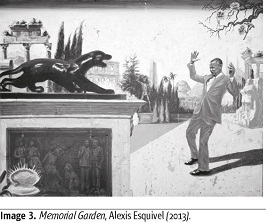

Alexis Esquivel, a self-described "black" Cuban artist, even though he is officially designated "mulatto," more directly addresses race and seems to be fascinated with U. S. President Barack Obama.(4) In his 2013 "history painting" Memorial Garden, Esquivel places the first African American president in an environment with historical icons such as the José Martí Memorial at the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana, ancient Greek or Roman ruins, the Great Sphinx of Giza and Pyramids in Egypt, and the 2011 controversial Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington D.C.(5)

The website Cuban Art News describes the painting as depicting President Barack Obama dancing, but he could also be backing away from the menacing black panther statue in the foreground (The Howard and Patricia Farber Foundation, 2015). Black panthers are believed to have mystical power in several cultures and were the symbol and name of a 1960s and 70s activist and controversial black power organization in the U. S. Esquivel's Cuban perspective allows him to portray the U. S. president in an orange suit and unpresidential pose that might be perceived as disrespectful in another context. The pose sources an official photograph of President Obama (in a navy blue suit) playing with a child in the White House (Wyler, 2012). President Obama allowed photographs of himself in casual situations to counter expectations that he must appear more decorous than a white president would. Black Cubans retained more African-ness in music, religion, and other aspects of culture than African Americans, who were expected to completely assimilate "whiteness" to prosper in the society. Under those slowly fading expectations, presumably the first black president would not want to be portrayed in any way that seemed to lack decorum (image 3).

Working in various media in addition to painting, Esquivel looks at relationships of power and race in society. He layers power, history and painting itself to articulate his concerns about what it means to be black in Cuba. In Smile, You Won! (2010) Alexis Esquivel represents President Barack Obama without a face, referencing a common critique leveled by the Cuban regime against U. S. oppression of African Americans. The title and figures suggest the irony that a black man can't win, because of the history and literally (in the painting), layers of imperialism and white dominance represented by images including the triumphant arch in the background. The American president, missing his eyes and nose, smiles down on a representation of himself (still smiling) as a mujahadeen terrorist, referring to the persistent questioning of Obama's nationality and loyalty to the country he leads. Painting the president with only red lips and white teeth for a face and adding the smiling dentures, Esquivel alludes to carefully constructed portrayals of African Americans as grinning, childish "darkies" -images that proliferated during the post-Civil War Reconstruction period and persisted into the late twentieth century (Nuruddin, 2010). The wide, white-toothed smile represents a particular icon of blackness and Obama's painted pink skin perhaps represents the binary reduction of his biracial heritage.

Unforgettable, Esquivel's large 2014 painting of Cuban President Raúl Castro and U. S. President Obama, recreates the leaders' historic handshake at Nelson Mandela's funeral in 2013. The title refers to African American singer Nat "King" Cole's performance of one of his signature songs at the Tropicana Cabaret in 1958. The painting highlights Esquivel's confidence as a documentarian and historian -for all Cuban people -through his paintings. For Esquivel, the handshake between the two presidents is as significant for Cuban history as "the crossing of the Delaware River by General George Washington in 1776" (Chichuri, 2014). He makes a cultural icon of the two men who will lead the impending sea change in Cuba/U. S. relations. Acting as a social historian as much as an artist, Esquivel makes monumental paintings for monumental events.

Alexis Esquivel exhibited in and helped organize the first version of Queloides: Race and Racism in Cuban Contemporary Art at the Casa de Africa, Havana in 1997. Six of the ten artists in that show also exhibited in the 2010 iteration, curated by Cuban artist Elio Rodriguez Valdes and Alejandro de la Fuente, professor of history and Latin American studies at the University of Pittsburgh (de la Fuente and Rodríguez. Valdés, 2011). First exhibited at the Centro Wilfredo Lam in Havana in spring 2010, the exhibition was then mounted at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh from October 2010 through February 2011. Queloides (keloids), are scars that heal, but never go away. Keloids are believed to be more common in black people than in white people. In the context of the exhibition, a mental image of a permanent raised and expanded scar in place of the original wound acts as a metaphor for slavery's resonant effects in Cuba. Discussions of race and racism happen more openly in Cuba than they did twenty or more years ago, but it seems that in talking about it, the revolution's explicit denunciation of racism must be considered. José Martí, who defined Cuban nationalist ideology, wanted to create a Cuban identity that transcended the identities of "black," "white," and "mulatto". Castro's revolutionary government outlawed institutionalized and legal practices of racism in 1959, several years before the civil rights movement in the U. S. provoked similar legislation (de la Fuente, 2001). Racism is still practiced in subtle, overt, and insidious forms in both countries, but in the U. S., race is discussed more openly in the public sphere, even though it remains a volatile subject.

In Cuba, as in the rest of the world, there is an unwritten hierarchy of skin color and hair texture that elevates white European looks even though most people currently in Cuba are people of color (de la Fuente, 1999). Tourist shops sell black caricatured figures that African Americans see as offensive and derogatory, although some black Cubans see them as benign kitsch. The African American Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson, who wrote Last Dance in Havana, observed in 2000, "Cuban race relations are thus conducted on the individual level, and because of cultural factors they lack the element of confrontation" (Robinson, 2000). While the level of discourse on race is nominally more progressive in the U. S., there is more actual everyday interaction between races in Cuba and much less physical segregation.

As Alejandro de la Fuente wrote in the Queloides exhibition catalog, "Cubans frequently proclaim that everybody on the island has some "Congo" or "Carabal" ancestry, but real Congo descendants must walk around ready to furnish their identity papers to the police" (de la Fuente, 2010). Economic disparities and everyday discriminatory treatment make the revolution look different to Cubans who are more directly descended from African slaves rather than European Spaniards. De la Fuente goes on to say that the keloid scars of unacknowledged racism "must be exhibited, painted, sculpted, photographed, carved and etched" (de la Fuente, 2011).

In keeping with this metaphor, the introspective artists of the Queloides exhibition all deal with race pointedly and sometimes angrily. Their connections to the African diaspora show up in a range of ways. Some, like Alexis Esquivel, refer to the plight of African Americans, while others refer to pre-diasporic origins. Belkis Ayón's work, about the secret society of Abakuá, has the most direct connections to African folklore and rituals (de la Fuente and Rodríguez Valdés, 2010). Other artists are grounded in a wider sense of diaspora and African identity -Armando Mariño's sculpture The Raft (2010) of a group of barefoot black people replacing the wheels of a 1950s American car alludes to traditional and contemporary African figure representations such as the life-size painted wooden figures carved by Ivory Coast sculptors Emile Guebehi and Nicolas Damas.

When the exhibition was initiated in Havana in 1997, it started a public conversation on race filtered through art. The artists who still live in Cuba risked being viewed as challenging the cubanidad ideal of racial harmony. Like hip-hop artists and filmmakers in Cuba, these visual artists expanded the space for conversations about racism. Despite its controversy, the initial exhibition was permitted in 1997 -reinforcing the theory that the arts can shape public discourse on essential topics within a socialist government structure.

Alexis Esquivel's robotic installation Urban Sarayeye(6) in the exhibition refers to collected fruits and gifts that people who follow Afro-Cuban rituals leave in public spaces as offerings to the gods. The robot, VAPROR-2059 performs the task of collecting the offerings for disposal as part of current civic sanitation practices. using the robot addresses the complicated problem of respecting black people's religious practices while keeping public spaces clean and avoiding negative spiritual powers. In the piece, the prototype avatar eliminates the need for sanitation workers to directly touch the offerings and solves a potential cultural conflict. Esquivel's game-like installation uses humor to illuminate the dissonance embedded in Cuba's complex racial environment.

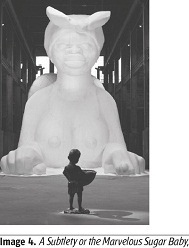

The environment for black U. S. artists is somewhat different. People of African descent -known as black or African American -make up about 12 % of the U. S.'s 300 million people. Perhaps because black people are a relatively small minority of the total population, social and political statements African American artists make in their work are seldom seen as universal. For example, more than 130 000 mostly white people walked through African American artist Kara Walker's 2014 Sugar Sphinx installation in Brooklyn, New York over nine weeks. Probably few of those visitors connected themselves to the narrative of something as ubiquitous and seemingly necessary as sugar tied to the systematic subjugation and mistreatment of people -from the slaves brought to the New World to harvest sugar cane to the workers in the now defunct Domino Sugar Factory that processed and packaged it for mass consumption. Almost everyone eats sugar, but not many people can easily connect its pervasiveness in the American diet to a manufactured desire based on production possible through slavery. Kara Walker's piece makes those connections (image 4).

Walker's work usually confronts issues of race and U. S. slavery, but her 2014 colossal installation known as the Sugar Sphinx addressed the entire Caribbean sugar/slave trade, which also involved Cuba. Exhibited widely and celebrated at major art museums for more than two decades, Kara Walker's controversial work confronts the sexual legacy of slavery that is almost never discussed, but is apparent in the ubiquitous physical results of miscegenation. The full title of her installation is: "A Subtlety: or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant" (Creative Time, n. d.). "A subtlety" refers to "the sugar confections that were served at medieval feasts and that are the predecessors of contemporary wedding cakes" (Boucher, 2014).

African American artists have used visual art for protest since the 1920s and 30s Harlem Renaissance, celebrating blackness and connections to Africa to counter the push to assimilate into white-dominated U. S. culture. The early 1960s Civil Rights movement initially did not include visual protest from African American artists. Later in the decade and into the 1970s Black Power and Black Arts Movements, visual work about black pride became a common tool of protest and empowerment. Artists in the Queloides exhibition used the "artistic public spheres" of their native Cuba and the U. S. to provoke conversation about racism. Even though racism persists throughout the African diaspora, each country has its own specific strain. The Queloides exhibition in Pittsburgh in 2010 showed how Cuban artists, now living inside and outside Cuba, looked introspectively at their own country's racial issues. The venue invited comparison to the ways racism manifests itself in the U. S.

The pointed politics in so much contemporary conceptual Cuban art is desirable in the international art world partly because it offers perspectives from outside of capitalism. The irony in that situation seems to reveal that the proliferation and easy dissemination of speech and expression built into a capitalist democracy makes the arts less relevant as a cultural mirror or fount of knowledge and insight. In the U.S., artists can make damning critiques and comments without reprisal, but their messages are often marginalized and usually not included in serious discussions of culture or politics. Arrechea's sculptures on Park Avenue lampooning icons of the American commercial landscape probably elicited smiles as architectural follies as much as cultural statements, even though they parody the foundations of capitalism in a stretch of Manhattan that is home to many of the wealthiest people in the world. Americans are accustomed to critiques of capitalism. The Occupy Wall Street movement, which started in 2011, drew attention the 1 % who have more wealth than the bottom 95 % of Americans combined. News of corporate corruption and greed is so ubiquitous it must be spectacular to keep the public's attention for more than a short time. People in the U.S. are fascinated with all things Cuban as a kind of forbidden fruit that grew out of the embargo and lack of communication between the two countries. Along with the rest of the art world, curators in the U.S. value the incredible arts traditions, training, and creative vision in Cuban art. The fact that artists in Cuba are perceived to have social agency and can reach people through popular culture gives them an opportunity to participate in national conversations as the two countries negotiate their differences.

People in the U.S. are fascinated with all things Cuban as a kind of forbidden fruit that grew out of the embargo and lack of communication between the two countries. Along with the rest of the art world, curators in the U.S. value the incredible arts traditions, training, and creative vision in Cuban art. The fact that artists in Cuba are perceived to have social agency and can reach people through popular culture gives them an opportunity to participate in national conversations as a new relationship with the U.S. moves forward and the two countries negotiate their differences.

Looking at African American art that directly addresses race might open new dialogues in Cuba on the subject. U. S. artists might seek more validation as agents of cultural and societal change. As establishing an official diplomatic relationship between the two countries has been established, the arts might provide a creative and receptive space for parsing similarities and differences, finding common progressive ground, and building better societies on both sides of the ninety miles of sea separating the two countries.

Bibliography

Angeline, J. (2013): "Alexandre Arrechea", ArtNexus, n.º 89, Arte en Colombia, n.º 135, June-August, <http://www.artnexus.com/Notice_View.aspx?DocumentID=26313> [12/6/2015].

Boucher, B. (2014): "Art In America", Art in America Editorial, 10 July, <http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/news/kara-walkers-sugar-sphinx-draws-130k-visitors-up-to-10kday/> [22/6/2015]. Kara

Walker's Sugar Sphinx Draws, 130 000 visitors, up to 10 000/Day.

Candelaria, C. (2004): "The nature of Cuban identity which has African, Spanish, and native Taíno roots", Encyclopedia of Latino Popular Culture, vol. 1 "A-L", Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, p. 448.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (n. d.): "The World Factbook", <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/cu.html> [29/5/2013].

Chicuri Mena, A. G. (2007): "Belkis Ayón", The Farber Collection, Cuba Avant-Garde, Contemporary Cuban Art, <http://www.thefarbercollection.com/artists/bio/belkis_ayon_manso> [31/1/2014].

Chichuri Mena, A. G. (2014): "Unforgettable: Obama, Raúl, and Alexis Esquivel's Chronicle of Hope", Cuban Art News, The Howard and Patricia Farber Foundation, 18 December, <http://www.cubanartnews.org/news/unforgettable-obama-raul-and-alexis-esquivels-chronicle-of-hope> [17/6/2015].

Creative Time (n. d.): "Kara Walker's "A Subtlety" On View Through July 6", <http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/> [22/6/2015].

Cuba Plus Magazine (2009): "Photofeature Nelson & Liudmila", vol. 17, March, <http://www.cubaplus.ca/volume17/photofeature-nelson-liudmila> [2/6/2012].

Cuban Art News (2015): "Biennial Preview: Alexandre Arrechea's The Map of Silence", 9 April, <http://www.cubanartnews.org/news/biennial-preview-alexandre-arrecheas-the-map-of-silence/4435> [12/6/2015].

Dahl, J. (2013): "Trayvon Martin Shooting: A Timeline of Events", CBS News, CBS Interactive, 12 July, <http://www.cbsnews.com/news/trayvon-martin-shooting-a-timeline-of-events/> [22/6/2015].

de la Fuente, A. (1999): "Myths of Racial Democracy: Cuba, 1900-1912" Latin American Research Review, vol. 34, n.º 3, pp. 39-73.

de la Fuente, A. (2001): "The Resurgence of Racism in Cuba" NACLA Report on the Americas, vol. XXXIV, n.º 6, May/June, p. 30.

de la Fuente, A. (ed.) (2010): Queloides: Race and Racism in Cuban Contemporary Art, Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh.

de la Fuente, A. and Rodríguez Valdés, E. (2010): "Transcendent Belkis Ayón", Queloides, n.º 92, "Collography Method", Discover Graphics, Printing Methods, <http://www.discovergraphics.org/collography.htm> [1/6/2013].

de la Fuente, A. and Rodríguez Valdés, E. (2011): "Calendar of Events of the Mattress Factory Art Museum", The Mattress Factory Art Museum, <http://www.mattress.org/index.cfm?event=ShowExhibition&eid=96> [21/9/2011].

Dellinger, H. (2013): "Righting Two Martin Luther King Memorial Wrongs", The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 21 January, <http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2013/01/righting-two-martin-luther-king-memorial-wrongs/266944/> [22/6/2015].

Fallon, M. (2010): "Cuban Artists Grapple with Local Racism on a World Stage", Utne, <http://www.utne.com/blogs/blog.aspx?blogid=32&tag=identityArt#ixzz22RbRiLJJ> [19/10/2010].

Fausset, R. (2010): "Black Activists Launch Rare Attack on Cuba about Racism", Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, January 3, <http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jan/03/nation/la-na-cuba-blacks3-2010jan03> [22/6/2015].

Fernandes, S. (2006): Cuba Represent! Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures, Duke University Press, Durham.

Habermas, J.; Lennox, S. and Lennox, F. (1974): "The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964)", New German Critique, vol. 3, n.º 50, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/487737> [22/6/2015].

Haupt, G. and Binder, P. (2010): "Queloides: Race and Racism in Cuban Contemporary Art", Queloides, Universes in Universe-Magazine, May <http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/magazine/articles/2010/queloides> [17/6/2015].

Havana Club International (2009): "Alexandre Arrechea: Visual Artist" Havana-Cultura, <http://www.havana-cultura.com/en/int/visual-art/alexandre-arrechea/cuban-painter> [28/8/2011].

Havana Cultural (2009): "Havana Today: Yoan Capote & Liset Castillo", March, <http://www.havana-cultura.com/en/nl/visual-art/havana-biennial/yoan-capote-and-liset-castillo> [28/8/2011].

The Howard and Patricia Farber Foundation (2015):"Exhibition Walk-Through: Memorial Garden by Alexis Esquivel", Exhibition Walk-Through: Memorial Garden by Alexis Esquivel, 12 March, <http://www.cubanartnews.org/news/exhibition-walk-through-memorial-garden-by-alexis-esquivel> [22/6/2015].

Kino, C. (2014): "Kara Walker's Thought-Provoking Art", The Wall Street Journal [WSJ], 5 November, <http://www.wsj.com/articles/kara-walkers-thought-provoking-art-1415238221> [22/6/2015].

Knudsen, S. (2013): "Alexandre Arrechea: No Limits", ARTPULSE, June 2013, <http://artpulsemagazine.com/alexandre-arrechea-no-limits> [21/6/2015].

La Biennale Di Venezia (2015): "La Biennale Di Venezia. Special Project by La Biennale Di Venezia and Teatro La Fenice: Vincenzo Bellini's Norma", La Biennale, 20 May, <http://www.labiennale.org/en/news/06-03.html> [20/6/2015].

Laughland, O.; Swaine, J. and Lartey, J. (2015): "U. S. Police Killings Headed for 1 100 this Year, with Black Americans Twice as Likely to Die", Guardian News and Media Limited, 1 July, <http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jul/01/us-police-killings-this-year-black-americans?CMP=share_btn_fb> [10/9/2015].

Library of Congress of United Stated of America (1837): "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?", <http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661312> [29/1/2014].

MagnanMetz (2013): "Large Park Avenue Sculptures", <http://magnanmetz.com/no_limits/large_sculptures.php?image=_lo_AA_3518_Sherry%20Netherland.jpg> [29/5/2013].

Mccormack, D. (2014): "Protests Break out across NINETY Cities as Thousands March in Anger", Daily Mail, Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 25 November, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2848203/Protesters-gather-90-cities-U-S-grand-jury-decides-Officer-Darren-Wilson-won-t-charged-death-Michael-Brown.html> [25/6/2015].

McCormick, C. (2008): "American Abyss", Artnet, <http://blog.alexandrearrechea.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/alexandre-arrechea-artnet.jpg> [14/1/2010].

Milloy, C. (2015): "Black Women's Lives Matter, Too, Say the Women behind the Iconic Hashtag", The Washington Post, 19 May, <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/black-womens-lives-matter-too-say-the-women-behind-the-iconic-hashtag/2015/05/19/61d57798-fe4c-11e4-8b6c-0dcce21e223d_story.html> [22/6/2015].

Muteba Rahier, J. (1998): "Blackness, the Racial / Spatial Order, Migrations, and Miss Ecuador 1995-96" American Anthropologist vol. 100, n.º 2, Washington D. C., June, p. 421.

Nuruddin, Y. (2010): "Culture, Identity and Community: From Slavery to the Present", in Encyclopedia of African American History, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California, pp. 527-576.

Pascual Castillo, O. (ed.) (2010): "Creole Histories According to Alexis Esquivel", Queloides: Race and Racism in Cuban Contemporary Art, Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, pp. 121-153.

Pe?rez-Lo?pez, J. F. (1991): Preface, in The Economics of Cuban Sugar, Pittsburgh, PA, University of Pittsburgh, pp. I-XIII.

Robinson, E. (2000): "Cuba Begins to Answer Its Race Question", The Washington Post, November 12, <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/13/AR2009041301562.html> [12/6/2015].

Shaw, K. (2010): "Artists Address the Chronic Racism in Cuba", Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, December 12, TribLIVE/AandE, <http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/ae/museums/s_713203.html>, [5/9/2011].

Shutterstock.com (n. d.): "Afro American Old Styled Man Attacking with Machete or Sword", Photos, <http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-62908072/stock-photo-afro-american-old-styled-man-attacking-with-machete-or-sword.html> [29/5/2013].

ThinkQuest (2012): "Scale Model of Havana", Projects by Students for Students, <http://library.thinkquest.org/18355/scale_model_of_havana.html> [2/6/2012].

Thomas, H. (1998): Cuba Or the Pursuit of Freedom, Da Capo Press, New York.

Urofsky, M. I. (2015): "Jim Crow Law | United States [1877-1954]", Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 April, <http://www.britannica.com/event/Jim-Crow-law> [10/6/2015].

Vogel, C. (2013): "Struggling in Bronze: Figures Visit Central Park", New York Times, January 24, INSIDE (art section) New York, p.

Weiss, R. (2011): To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Wyler, G. (2012): "This Picture of Barack Obama and Baby Spiderman Is the Best Ever", Business Insider, 19 December, <http://www.businessinsider.com/obama-spiderman-picture-2012-12> [22/6/2015].

Zeitlyn, M. A. (2007): "What Could Happen If I Lie?", Alexandre Arrechea: Contemporary Artist, December 09, <http://blog.alexandrearrechea.com/2007/12/what/. Video available for view at http://alexandrearrechea.com/category/works?id=218&y=2006> [25/1/2014].

Zurbano, R. (2013): "For Blacks in Cuba, the Revolution Hasn't Begun", New York Times, Opinion section, March 24, <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/opinion/sunday/for-blacks-in-cuba-the-revolution-hasnt-begun.html> [22/6/2015].

RECIBIDO: 2/1/2017

ACEPTADO: 28/2/2017

Colette Gaiter. University of Delaware, U. S. E-mail: cgaiter@udel.edu

Notice Explanatory

1. In the U. S., race designations are often used when referring to people of color. This is not standard practice in Cuba, but is important in the context of this article.

2. In 1997, at the age of 28, Walker became one of the youngest people to win a prestigious MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant (Kino, 2014). Walker's work has been exhibited internationally and she is critically acclaimed as one of the most influential U. S. artists. These two artists, and others from a racial history that blocked their immediate ancestors from having basic human and civil rights.

3. Cuba was the major center of slave-dependent sugar production after Haitian independence in 1804.

4. Esquivel, who is considered mulatto in Cuba, told American journalist Eugene Robinson that he became radicalized when he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X for school and, "From that point, he identified himself as black" (Robinson, 2009).

5. The memorial was controversial because of a misquoted inscription and other aspects of the design and implementation (Dellinger, 2013).

6. Sarayeye: the art of cleansing or purifying.