Introduction

The Giant African snail, Achatina fulica Bowdich, 1822 has been introduced throughout the tropics and subtropics and has been considered the most important snail pest in the world. In Cuba it has been introduced in 2014 for African religious purposes.1 Nowadays, mainly by human activity, A. fulica is widespread all over the country, where it is a pest in ornamental gardens, vegetable gardens, and small-scale agriculture.2

Achatina fulica is also a public health concern since it is intermediate host of the Metastrogyloidea nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen, 1935), which causes eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in humans, notable cases having been reported in Cuba since 1981.3,4

Angiostrongylus cantonensis normally resides in rat lungs where it lays eggs in pulmonary arteries. Larvae subsequently hatch and migrate via the trachea and gastrointestinal tract into rat feces. First stage larvae are consumed by snails and slugs, then develop eventually into infectious third stage larvae, often in extremely high numbers. Rats and humans become infected by eating infected snails or contaminated uncooked vegetables. In man, many larvae migrate to the brain where they cause abscesses, brain swelling, and hemorrhage.5

Additionally, worms can travel to the spinal cord where they also eventually die and degenerates.

Since Havana is currently experiencing the explosive phase of the invasion with big specimens of A. fulica occurring in dense populations in urban areas, LABCEL (Laboratorio Central de Líquido Cefalorraquídeo ) has been examining samples of A. fulica sent by the medical students Map of Havana showing the municipalities with samples of Achatina fulica examined for Metastrongylidae larvae in order to determine the health risks for human population and for other implications. While examining those samples nematode larvae were obtained and morphological and morphometric analyses were performed. This is the first report of the development of A. cantonensis infective larvae from several localities in Havana, found in the interior of the pallial cavity of A. fulica evidencing the human importance of this mollusc in the potential transmission of A. cantonensis.

Methods

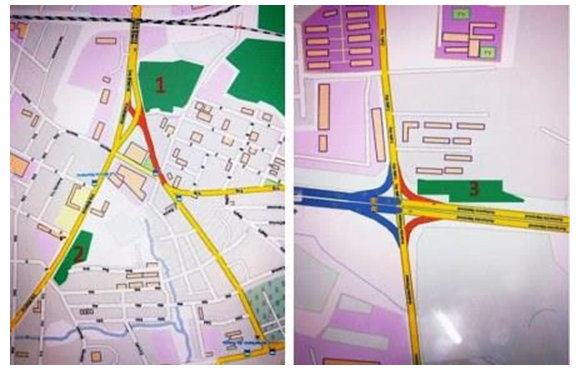

The technique of Lobato-Paraense modified under the laboratory conditions was used for the examination of 20 specimens of A. fulica received in Laboratorio Central de Líquido Cefalorraquídeo (LABCEL) in August 2019. It were examined from Regla and San Miguel municipalities (Fig. 1)

1 and 2: zones from Regla municipality 3: zone from San Miguel del Padrón municipality

1 and 2: zones from Regla municipality 3: zone from San Miguel del Padrón municipalityFig. 1- Geographical localization of snails collection.

The cephalopodal mass of A. fulica specimens were individually extracted

The viscera and the pallial organs of the molluscs were placed in Petri dishes with saline solution (NaCl 0,9 %). Some parts of the pallial membrane was cotted and placed on microscope slides and was observed in Carl Zeizz light microscopy as well as the sediment collected from the bottom of the assay tubes, were examined under microscope for helminth larvae. For light microscopy collected larvae were washed twice and examined under an Carl Zeiss light microscope. The morphometric analyses were made under a Zeiss Standard microscope with the aid of a phone camera. Larvae movements were recorded in an mp4 format using a mobile camera. Representative specimens of strongylides larvae were collected in the digital helminthological collection of LABCEL.

Results

From 20 specimens of A. fulica examined, 10 belongs for each municipallity. Five were infected with strongylides from Regla Municipality (50 %), and 3 (30 %) with strongylides from San Miguel Municpality. In figure 2 appears a strongylide encapsulated in the palliar membrane of L. fulica snail.

The morphological parameters of the third larval stages (L3) are shown in figure 3. The form and structure of strongylides of A. cantonensis larvae were compared to those obtained by Martini L in 2016 from Ecuador.5

Fig. 3- Third stage (L3) larve. It can observed their content with a remarcable interior structure as the aesophagic bulb, intestine and anus.

Characteristics movements of A. cantonensis larvae can be observed in the following video.

Third stage (L3) larva. Notice its characteristic movements

In adult’s snails, that was differentiated by it higher size and for its less intensive color of their shells was the ones with more positive larvae recovery. It is due because L fulica was collected from open air garbage deposits where the rats and their feces have more chance to infect snails.

Discussion

The recent introduction of A. fulica in Cuba must be regarded with caution by health authorities. The human activities in addition to its high reproductive capacity and lack of natural pathogens have led to rapid dispersal even among distant regions including the Cuban eastern provinces. The present study registered the stronglylides of A. cantonensis in this mollusc indicating also its potential as health damage for humans.

A. fulica can also become intermediate hosts of parasites of wild animals becoming a risk for the wild fauna biodiversity. In addition, the large numbers of this mollusc in areas of variable human population densities, i.e., faraway and urban populations, increase the changes of emergent zoonoses.

Considering all those aspects, we emphasize the need for further investigations of the potential intermediate host capacity of this mollusc for Cuban endemic parasite like A. cantonensis of human interest besides the sanitary vigilance of snails and rats from vulnerable areas for A. cantonensis introduction as the port and airport side areas.