INTRODUCTION

Workplace Violence is defined by World Health Organization as “incidents where employees are abused, threatened, assaulted or subjected to other offensive behavior in circumstances related to their work”.1 In recent years the increasing evidence showed that the incidents could happen inside health institutions or on way to work affecting the workers’ health, their motivation as well as the quality of care provided.

Several studies have established that all members of health team face workplace violence throughout their career.2,3,4 the main sources reported are coworkers5 and patients or their relatives. Likewise, is regarded as a major health and safety issue for healthcare workers.6 However, the review of the literature revealed that nursing staff is more likely to experience physical violence and bullying than other health worker’s.6,7,8,9

In spite of Workplace Violence has been large considered as a public health problem, the majority of studies in Ecuador have tended to focus on prevalence rather than on well-being affectation and protecting measures available in the health institutions. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to research the perceptions of workplace violence in nursing staff in association to type of violence, perpetrators, consequences and protecting measures available in the health institutions.

METHODS

A qualitative study with phenomenological method was carried out in one of the major hospitals in Quito, Ecuador. Researchers intended to illustrate the structure of the experience about how is perceived the workplace violence (intuited object) between nurse’s participants in this study.10 The results are part of the research project titled: “Manifestaciones de la violencia de género hacia el personal de enfermería en el lugar de trabajo en instituciones del tercer nivel de atención [O13080]”.

The sample recruitment strategy selected was a convenience sample of non-probability approach. The predominant criteria were the willingness to participate in the study, time available and confidence between participants. The researchers recruited n = 13 professional nurses that participated in Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with support of the area supervisors who informed their team the day and place where the study will be done. They were asked on incidents that occurred during the previous 12 months. Eligibility criteria included being professional, over age of 18, and employers at the hospital with at least 2 years.

The technique decided for data collection was FGD because it addressed the research goals of our main study and allowed to analyze the phenomenon together with the interaction of the group members. The research team conducted one focus group and established for the “saturation of the information” the theoretical orientation of Glasser and Strauss (1967) this term is defined as “no additional data are being found whereby the researcher can develop properties of the category”.11 It was reached in each of themes explored during discussion. Data were collected in July 2018.

FGD was moderated by the first and corresponding author, second and third author assisted as non-participant observers. They took notes about the interactions between participants. Researchers used the Question Guidelines for Focus Group Discussion recommended by International Labour Office, International Council of Nurses, World Health Organization and Public Services International. The meeting took 01:34:56. The narratives were recorded and stored in voice files using a digital recorder. Then, recordings were transcribed in Microsoft Word version and added to Atlas ti.

The Mayring’s approach was used for the interpretative process which was useful for the building of categories based on two central approaches: deductive category application based on questions guidelines for FGD and inductive category development focused on the interpersonal communication among researchers and participants to discovering perspectives about the phenomenon that were not previously identified.12,13 The feminist epistemological framework was utilized to analyze the power imbalances in the work of relationship and the context in which it occurs.

The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador [2018-20EO] and the research committee of the hospital mentioned. Written informed consent was signed by each participant and before starting the data collection, they were informed about aims, procedure, confidentiality, and free nature of the study. Participants and the name of the Hospital were anonymized with the intention of guarantying the confidentiality in this sensitive context.

RESULTS

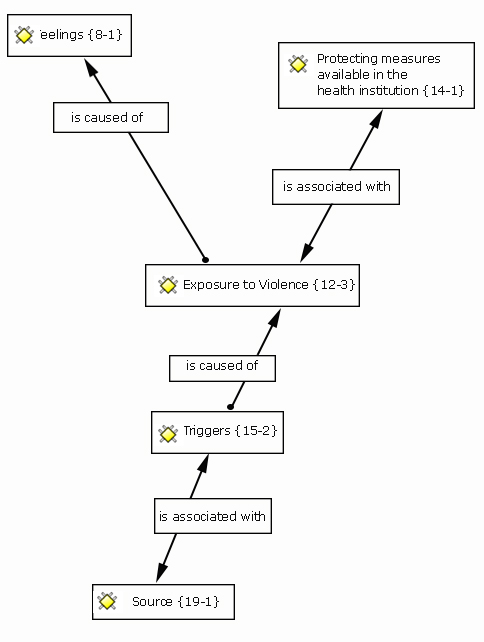

The main themes were organized in categories: exposure to violence, source, feelings, triggers, and protecting measures available in the health institutions. The researchers integrated each category in a semantic network to represent the complex linking between them. The intuitive graph referred the cognitive model and is part of the theorization process (Fig.).

Source: Created with the Atlas.ti software. It showed associations and causes of the phenomenon studied based on the participants’ explanations in the FGD.

Exposure to violence

Nursing staff expressed during the discussion clarity about what constitutes violence in the workplace such as understanding about the magnitude of the problem. The descriptions in Focus Group provided an individual view of the problem but they also spoke for many colleagues that they had the experience with these incidents.

P1: “Speaking in an aloud angry way or mistreatment is the most frequent complaint. I have not had the experience but I have heard when the expressions of patients toward my colleagues, the nurses are called stupid or incompetent if they do not have what they need immediately”.

P3: “Verbal abuse is not the only kind of violence. We face also physical violence. We have a colleague who was beaten by a psychiatric patient. He broke her nose”. P4: “A relative of a patient asked me: Why did not you attend my mother? He was going to hit me but a man stopped him”.

P7: “A coworker physically abused (hitting) another worker”.

P8: “It is difficult to face the mistreatment between colleagues at work more than patients or relatives”.

Nurses narrated their experiences with violence while the researchers identified physical violence and psychological (verbal abuse, threats and bulling/mobbing) as the most common forms of violence in this specific setting.

Feelings

A common narrative between participants was the emotional pain because they were not able to solve the circumstance when they experienced physical violence or non-physical (verbal abuse, threats). From participants’ point of view, the exposure to violence else just causes bad feeling in the workplace, some examples were given during discussion.

P2: “Bad mood and impotence”

P5: “You can never answer them in the same way, you have to be silent and after that you feel humiliated”.

P6: ¡To be quiet! I just learnt it with the age because nobody hears you.

Moderator: ¿Do you thing “to be quiet” is the best option?

P6: Maybe it isn’t the best option but it works to me. I have decided to shut up for myself, if a colleague, patient or relative mistreats me, I let it go I don’t want to become a bitter person. I prefer to stay with the best thing of the day.

P9: You are an insensitive person.

P6: No, I don’t. I am a sensitive person like you, I sometimes feel bad, I sometimes cry and keep the sadness within me but I say nothing because I think that won’t have change.

P11: “If you report this kind of incidents, then the responsible for acting ask why it happened, what did you do? And in consequence you feel like a loser, whatever you do, you always feel that will have negative consequences”.

It was identified during the discussion a negative engaging which would involve feeling guilty and lacking of institutional protection.

Triggers

Participants shaped the pressures faced during their time working to provide care and the low tolerance demonstrated by patients and relatives. They considered the health policies and insufficient staff were the potential causes of the exposure to violence in the workplace.

P13: “It is the workload, the excess of work, the conditions in which we are right now, for example I work in the area of consultations and each doctor should assist 20 patients per day. In addition, they have an open schedule to assist six patients more but today the doctor attended 41 patients”.

P10: “I think, there is staff shortage because of the standards of care are not met, frequently the patient ratio exceeds the number of doctors or nurses established. So if I agree with my colleague when she says that a cause of violence is the workload”.

The goal of universal health coverage (UHC) in Latin-American has been assumed as strategy for many countries to increase the access of the population to health services without discrimination but the improving of health care services requires financing and opening to broaden the nurse competencies such as advanced practice nurses after professional education, it will be a possibility to take advantage of human resources in the health sector.

Source

The violence came mostly from patients, relatives, staff members or supervisors according to the collective answers. This category is associated with the triggers of violence in the workplace because the narratives showed that some patients or relatives were unsatisfied with the care assistance and their responses intensify in different levels of violence.

P1: “In my experience, violent offenders are most often family members than patients”.

P4: “It´s true! Usually patients are grateful with us because they need our care”.

P6: “We received the worst treat from patients that belong to the insurance network. Mostly they are not militaries”.

P7: “Sometimes as nurse you give a recommendation to improve the services working. However, the answer from military worker is you are not my boss, they do not see us as professional. They keep in mind their hierarchy (…) if our supervisors are militaries then they treat us like a subordinate”.

Protecting measures available in the health institution

This category is associated with exposure to violence because represents the process to handle the problem at the Hospital. Participants were asked about the ways of dealing with violence in the workplace. The opinions took up positions within the group. Some participants expressed that the Hospital does not have internal procedures for treating with violence and another group of participants mentioned that the Hospital has internal procedure but only for physical violence.

P2: “After a violent incident if you want to report the situation there is not a notification form. I mean, we have rights too”.

P3: “We have a colleague who was beaten by a psychiatric patient. He broke her nose”.

P7: “A coworker physically abused (hitting) another worker”.

Both versions were verified at the human resources department and it was evidenced that in the case of physical violence, the health institution had an internal procedure. It was handled through occupational health service and the Hospital provided coverage of the medical costs. The incident related to the physical aggression between coworkers was handled with an external agency (court of justice).

Specifically, in the case of psychological violence (verbal abuse incidents or threats) was expressed by participants that nurses affected mostly try to ignore the situation because they considered this to be a typical incident in the workplace. They did not report the situation and it has caused underregistration.

DISCUSSION

The researchers found that some aspects of the phenomenon descriptions were based on intersubjectivity of participants.14 This was evidenced more often when the group was not affected directly by violent incidents. Nurses in focus group shared meanings built on the interaction with other coworkers of their Hospital. However, some results showed experiences of their own lived-body10 in which participants were victimized.

The results of this qualitative study showed that the participants perceived workplace violence as a significant problem. The opinions tended to considering that these incidents were affecting equally all health workers at the Hospital. The participants narrated experiences with physical violence being patients6 and staff members15 recognized as aggressors. On other hand, psychological violence was committed by a wide range of individuals (patients, relatives, colleagues and supervisors). It was found that the direct threat based on the use of physical force was the concerning issue for the nurses in the focus group discussion, this abusive behavior was shown in the patients' relatives.

These outcomes are in the line with a previous study in which one out of every four health worker experienced physical violence at the workplace. Threats or insults were reported by almost 60 % of respondents; over 40 % of participants reported inappropriate and degrading attacks (i.e., spitting) in the workplace 12 months before the survey.16

Similar situation was reported in another survey a total of 95 % of responders were exposed to verbal aggression, around one third (33 %) to physical aggression. The extent of verbal aggression was similar for doctors and nursing staff, whereas almost every second nurse (46 %) but “only” every fifth doctor (22 %) reported physical violence during this period.17

Specifically, verbal abuse was identified in our study as the most common type of violence in the workplace perpetrated mainly by the patients' relatives. This result was consistent with some international studies about workplace violence that displayed a frequent description of this phenomenon.16,18,19,20 In spite of there are in Latin-America very few qualitative studies on workplace violence, quantitative researches showed also higher prevalence rates of verbal abuse and mistreatment toward nursing staff and other health workers.2,21

Participants in this research described their feelings such as humiliation, impotence, and lack of protection. For these results would be necessary to answer other questions in further research such as immediate effect (ability to perform tasks or to keep the concentration) and potential late effect (job satisfaction or motivation) which has been before verified these feelings decreased quality of work, greater psychological demand, and decreased control over tasks.19,20,22,23

It was verified during discussion in focus group that incidents were efficient handled and reported when physical violence was involved. Nevertheless, there was a discrepancy in terms of psychological violence (verbal abuse, threats, and bullyng/mobbing) because the results indicated that nurses often remained silent. The reason expressed was that the organization did not have internal procedure to make a complaint in these cases.

The characteristics of the health institution in this study showed a pyramidal structure being a major disadvantage for the nursing profession the coordination of some duties between coworkers (militaries-civil professionals) and the relationship with the clients. The narratives showed that the interrelatedness focused more on dominance deference by a hierarchal work environment than the task or professional concerns. The results obtained in this study allowed to compare the nursing power in relation to the analyzed context which evidenced the existence of structural inequalities interconnected with the traditional patterns of power relations24 and beliefs about gender embedded in professional work.25,26 that could suggest a negative impact of all efforts to ensuring of the quality in health care.

This qualitative study allowed us to provide a contextualized understanding about the human experience with workplace violence which was perceived by nursing staff as a significance problem in magnitude and severity.

The exposure to physical violence or non-physical caused emotional pain in nursing staff which could be minimized through a preventative aggression program in the Hospital as well as the internal procedure implementation to document also the psychological incidents. From our point of view, there are also lack of diffusion about the internal procedure for dealing with physical abuse.

Participants expressed that the health policies and insufficient staff were the potential causes of the exposure to violence in the workplace being patients, relatives, coworkers and supervisors identified as aggressors.

It was evidenced the existence of structural inequalities interconnected with the traditional patterns of power relations. The nursing staff expressed that was harder for them the achievement of certain duties (advice for coworkers) at the health institution which could affect negatively the working of the services, the work environment, and the professional imagen of the nursing.

Limitations of the research

Some questions could not be answered in these preliminary results such as the ability of nursing staff to perform tasks after abusive incidents, to keep the concentration, the motivation, and the influence of the workplace violence on the quality of care. The above mentioned are the key aspects to offer a comprehensive analysis of the problem. It would be necessary to consider for future examinations.