INTRODUCTION

The cultivation of sugarcane has had a great importance in the economy of the agricultural sector in Ecuador, not only because it is part of one of the most important links in the agricultural production chains, but also because it is the livelihood for a numerous group of families. Hence, it is an important source of employment and income generation for the National Agricultural GDP of 12%, (MAGAP, 2018).

The industrial processing of sugar cane in Ecuador aimed at making sugar, alcohol, molasses and brown sugar (Bravo and Bonilla, 2017). That is why, the recovery plan of the production chain aims to foster the planting of sugarcane in the available areas (MAGAP, 2018).

The potential of land suitable for sugar cane production in Ecuador is 675,932 ha, of which only 172,476 ha are planted, representing 25,71% of the total available (MAGAP, 2017). According to these data, from the total area planted, only 113,160 ha are intended for sugar production and the remaining 59,316 ha, to other productions, such as ethyl alcohol, brown sugar and ethanol. For the production of this latter around 10 000 ha are used.

Data from the Ministry of Agriculture of Ecuador (MAGAP, 2018), reveal that the total sugar production until that date exceeded 608 000 t, of which a small part was used for export. Currently, this cultivation has spread through much of the Ecuadorian territory, given the potential benefits of developing new agro-industries, as well as the expectations and opportunities that open around the development of biofuels. (Bravo and Bonilla, 2017).

The surface used to the production of sugarcane in percentage terms is distributed in the following provinces: 72,4% in Guayas; 19,60% in Cañar; 4,20% in Carchi and Imbabura; 2,4% in Rivers and 1,40% in Loja. That is to say, in the provinces where the six sugar mills existing in the Ecuador are placed (INEC, 2016).

According to Daza (2014), the Ecuadorian government prioritized the transformation of the Productive Matrix as one of the main avenues for the selective substitution of imports, allowing considerable savings from 2013 to 2017. This process aims to either improve agricultural yields of the crops from a productive intensification, by introducing technological packages or increase the productive areas.

Sugarcane is not far to this reality, so steps were performed to transform its productive chain, which bases its strategy on the aggregate value of its derivatives, such as ethanol, which mixed with 15% gasoline, could reduce by 53% the importation of high-octane gasoline until 2017.

Manabí Province, in spite of not being among the largest sugarcane producers in Ecuador, has a productive tradition dating back more than 100 years. According to Álava (2014), in the province existed a total of 1 187,94 ha planted of sugarcane, of which 62,56% was concentrated in the areas of Junín Canton. Average yields oscillated around 63,36 t/ha and the production exceeded the 76,76 t.

Taking into account these aspects, the Government of Manabí Province established the strategic guidelines for the development of sugarcane cultivation, which are directed, to:

The comprehensive and sustainable productive development, aimed at improving the competitiveness of products derived from sugar cane to boost the local economy;

Development of an agro-industrial complex in Manabí Province;

Access to specialized markets in sugarcane derivatives.

Moreover, the strategic objectives are aimed at:

The generation of local capacities from technology transfer;

Implementation of a genetic bank for the disposition of basic seed;

Determine the viability of implementing an agro-industrial plant for sugarcane processing and obtaining derivatives;

The strategic relationship between public sector entities and private;

Development of agro-industrial complex by the association of the producers;

Raise the quality in the production of derivatives.

The fulfilment of these guidelines and strategic objectives, as well as the increase of sugarcane production in Manabí Province are highly dependent on the introduction of mechanized technology, according to the conditions of production and agro-technical requirements of this crop, because, currently, except juice extraction, practically 100% of the work is done manually, using the muscular strength of men. A number of objective and subjective factors limit their introduction or utilization. They are related to the natural conditions of the areas where the crop is developed, the prevailing production system and the availability of resources, among others.

Considering these aspects, the importance of sugarcane development in these areas, and the role of mechanization in it, the present work aims to determine restrictive factors for the mechanization of sugarcane cultivation in Manabí Province, Ecuador

METHODS

The investigations began in April 2015, with an survey in Junín Canton (Figure 1), as this is the one with the largest planted area and therefore the most representative with 19 communities and 743 ha planted with sugarcane. Later, in May of the same year, the investigations were extended to the plantation areas of UTYPRAC association, that has 45 ha planted in Abdón Calderón, belonging to Canton Portoviejo. Finally, in August of the same year, sugarcane producers of ASESAGRA Association were included in Jipijapa Canton (100 ha). The vast majority of these areas are concentrated in the territory of Gramalotal Parish.

The survey method was used to collect the information from producers. The survey team integrated by technicians of the Support Centers for Integral Sustainable Development (CADIS), technicians of the Direction of Productive Foment from GPM, as well as by technicians of this direction in the Cantonal Government of Junín. The sample included 104 surveyed producers in Canton Junín, other 25 from Calderon Parish and 22 of Jipijapa Canton.

The implementation of the survey included the preparation of a questionnaire with the required information. Such questionnaire was based on the one previously drawn up by experts from the Development Agency of Manabí Provincial Government (ADPM) and it was adequate according to the objectives pursued. The questionnaire was socialized and consulted with experts in the thematic.

A template was developed in Microsoft Excel 2013, where a database was created with the information obtained directly from the surveys. To determine the concordance between the criteria issued by the respondents, Kendall coefficient of concordance (W) was determined by using SPSS 11.5 statistical processor. Its determination was performed according to the methodology described by Herrera et al. (2010).

Location points of the farms of sugarcane growers were georeferenced by using GPS s, as well as the facilities for post-harvest processing and derivatives obtaining. Photos and videos on plantations, transport means and post-harvest processing facilities were taken.

The sample of respondents included 104 growers of sugarcane in Junín Canton, which included the producers of ASACAMA and IMPAGUA sugarcane associations, 25 of the UTYPRACT association in Calderón Parish, and another 22 of ASESSAGRA association. In Jipijapa Canton a total of 147 growers were surveyed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Agroproductive Characterization of the Zones under Study. These zones have a rich and long productive tradition, from which crops of great economic importance have been established, such as sugarcane, cocoa, coffee, banana, fruit and corn, among others. Cattle raising has also been developed in a minor scale. In accordance with the declarations of producers surveyed, currently, more than 875 ha are destined to these crops.

In these areas the cultivation of sugarcane has a long tradition, surpassing the 100 years old in Canton Junín. In Gramalotal Community plantations with more than 50 years old were registered. This crop was developed from rudimentary practices based on empirical knowledge that have been passed down from generation to generation. They have as their fundamental characteristics, the low level of intervention of machinery, low level of application of fertilizers and products for disease and pest control, as well as, little use of irrigation systems. Those are typical characteristics of the production areas supported by small and medium producers in Ecuador (Vasco Pérez et al., 2015). Production of derivatives are mainly used for the artisanal production of Aguardiente and Panela (Quezada et al., 2015). Other derivatives such as sweets are also produced in smaller amounts, very similar situation to the ones of the producing countries of the area (Guisao and Zuluaga, 2011; Díaz and Iglesias, 2012).

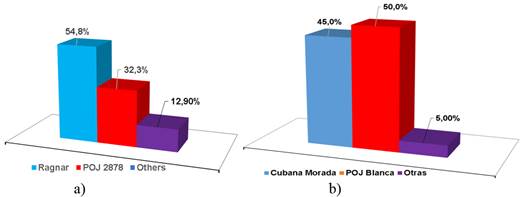

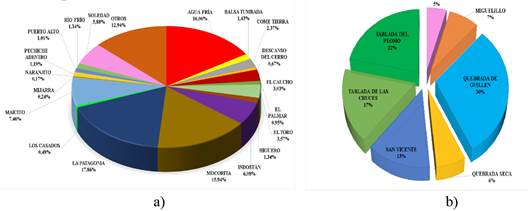

The specific calculation of the areas planted with sugarcane in the intervention communities showed, according to statements by the 104 producers, that over 743,2 ha are currently devoted to this crop in Canton Junín. Most areas are concentrated in the communities of Patagonia (17,86%), Agua Fria (16,06%) and Mocorita (15,94%). Figure 2a shows the percentage distribution of the areas planted by communities.

FIGURE 2 Percentage distribution of the areas planted with sugarcane. a) Junín Canton; b) Abdon Calderon

In the case of Abdon Calderon, the analysis of the areas planted with sugarcane, in the seven communities cultivated by the UTYPRAC association, showed (Figure 2b), that they cover 45 ha, distributed in greater amount under Quebrada Guillen Community (30%), Tabladas del Plomo and Cruces with 22 and 17%, respectively. San Vicente Locality will be added with 13%.

Finally, 100 ha of sugarcane cultivated by ASESAGRA association in Canton Jipijapa are mainly concentrated in the community of Gramalotal, with 90% of the planted areas (Figure 3).

The analysis of land availability and its distribution showed that there is great potential for further promoting the production of sugar cane in these zones because of the total of cultivable land available, only other crops occupy 10%.

Varieties

A thorough analysis of the sugarcane varieties most commonly planted evidenced that, in the communities of Junín and Calderon, Ragnar and POJ 2878, are those that have become most established and popular. That situation is observed in the provinces of the Ecuadorian coast (Arellano et al., 2009) as in other producing countries in the area (Alejandre et al., 2010; Viveros et al., 2015). That is due to their resistance to pests and diseases as well as adaptability to climatic conditions and required production potential (Arellano et al., 2011; Silva et al., 2011; Díaz and Iglesias Coronel, 2014; Arellano et al., 2015).

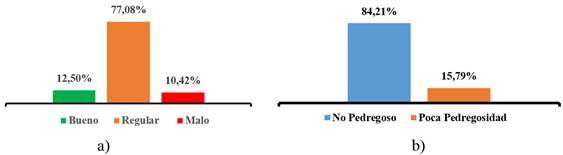

Of these varieties Ragnar is the most used, because 54,8% of producers reported using it in their plantations (Figure 4a). Another 32,3% of producers declared to use POJ 2878 variety. Both varieties are perfectly adapted in these zones. The rest of the varieties used do not show significant percentages compared to these two.

These varieties have high and erect stalk, have low levels of bed stalk, which is very favorable for mechanization, especially during harvest (Viveros et al., 2015).

The predominant framework planting in these areas is 1,60 m of distance between rows, per 1,0 m of distance between plants. This plantation frame is compatible with track width and running systems of the majority of the mechanized means traditionally used in harvesting and transporting sugarcane (Rípoli and Rípoli, 2010; Aparecido et al., 2013).

However, in the communities of Canton Jipijapa the situation is very different in the varieties employed and agricultural yields, because in these, the most commonly used varieties are POJ White and Cubana Morada, (Figure 4b). These varieties also are planted with a frame of plantation of 1,60 x 1,0 m, although in some plots, frames of 1.70 x 1 m have been established. Stalks are erect and easily lose their leaves during the harvest (Figure 10). These aspects favor the use of mechanized resources during harvesting and cultivation as long as conditions allow it (Novoa, 2009; Aparecido et al., 2013).

Agricultural yields in Junín and Calderon communities are below the potential yield (65 t/ha), because they oscillate between 35 and 45 t/ha. In the case of Abdon Calderón communities, the yields are greater than 45 to 50 t/ha. The difference is given, mainly, by years of over-exploitation of Junín plantations, without the benefit of chemical or organic fertilizers. The agricultural yield of sugarcane in these areas ranges from 80 to 100 t / ha, a figure that agrees with the national average of 93 t / ha (MAGAP, 2017).

Edaphoclimatic Characterization of the Research Area

Predominant soils in the investigated areas are classified as Mollisol + Entisol, Inceptisol, and Vertisol, with predominance of the latest, according to the map of taxonomic classification of soils in Manabí Province (MAGAP, 2012b). These soils are suitable for the cultivation of the sugarcane for their nature, characteristics, and constituents. They have fine texture, that is to say, having a clay content that varies from high to medium, allowing defining them as clayey or silty clayey soils. These characteristics make them to be classified as heavy soils, from the point of view of the difficulty for tillage (Cairo and Quintero, 1980). It means that they require greater tractive demand during soil tillage, hence, these aspects have to be taken into account for the selection of energy sources and tillage tools.

An analysis of soil condition based on experience and observation of producers and technicians’ surveyors showed that, 77,08% of the producers agreed that soils in regular or fair condition (Figure 5a) are soils suitable for the sugarcane production, but, fertilizer applications and appropriate crop management practices are necessary to reach potential crop yields in these areas.

Moreover, 84,21% of the producers decided that these soils are non-stony or have a null stoniness (Figure 5b). This aspect favors the development of sugarcane cultivation and its mechanization in the areas.

In plantation zones, land is very irregular. In most of them planted cane is located in terrain with slopes ranging from 50 to 70%, making it virtually impossible to use conventional machinery. This aspect represents the main limitation for the introduction or use of mechanized means in the production of sugarcane in these areas.

The climate of Manabí Province, in general, is tropical mega thermic, showing wet, dry, semi-arid, and semi dry variants.(MAGAP, 2012a, c). In areas where sugarcane plantations are investigated, the prevailing climate is mega thermic dry and humid mega thermic. Both climatic conditions are favorable for the development of sugarcane, because the volume of annual rainfall satisfies the 1 500 mm required by this crop (Woldea and Adaneb, 2014), exceeding 1 700 mm for the wet case. Average temperatures in these areas vary from 23 to 26 ° C depending on the time of the year (MAGAP, 2012c), that is, they satisfy temperature ranges required for the crop development at different stages (Woldea and Adaneb, 2014; Melloni et al., 2015).

Characterization of Mechanized Technologies and Agro-technical Deadlines

The analysis of the collected data showed that in these areas, the producers performed manually the different agro-technical tasks required by this crop, with low level of use of agricultural machinery; the use of these means has been limited to the labors of primary preparation of soil. Of the total of 151 surveyed producers, only six of them reported using machinery, representing 3,95% of the total.

Similarly, it was found that there is very little availability of machinery for conducting these workings in both zones. Producers who use machinery, the rent at a cost ranging from 80 to 100 $/ha.

The soil tillage is carried out in most cases without having established or defined the most suitable technology for the conditions of these areas. The whole process of soil preparation is done with a disc harrow or row plow fragmenting the soil until it is fluffy before furrowing and planting. The continued use of these means favors the emergence of hard and plow pans, or what is the same, compact the soil below the maximum depth of tillage (Hossne, 2004), as well as erosion or soil loss (Liu et al., 2016).

For the rest of the agro-technical labor required for sugarcane cultivation, no cases of use of agricultural machinery were reported, including cutting and hauling during harvest.

The size of the parcels is another limiting factor for the introduction of machinery, as these have an equivalent mean area to 0,705 ha (1 block), making it difficult and expensive the use of these machines. There is neither availability of machinery that suits to work under these conditions nor trained producers on their use.

In these areas most of the agrotechnical tasks during cane cultivation is done manually, by occasional hiring of day laborers who work for a salary that ranges approximately between 10 a12 USD/day. In these areas, there is a great availability of labor, which favors the performance of these tasks manually.

Soil preparation usually starts from December to January, when most producers carry out the planting of the new areas, to take advantage of the rains associated with winter. The rest of the tasks such as weeding, hilling, fertilization, pest and weed control, are carried out manually during the course of the year.

Harvest and Transport of Sugarcane

In the areas investigated, the harvest of sugarcane is done manually, both cutting and rising is carried out under this modality (manually). A system of selective cutting of the stalks is used, according to their degree of maturation, that is to say, only the stalks with greater maturity are harvested. The stalks are cut in halves and are manually translated out of the field (Figure 6), where they are transported to the sugar mills for processing.

The transport of sugarcane stalks harvested to the processing centers is carried out with the help of labor animals or by means of automotive transport with a maximum capacity of 2 t. These variants (Figure 14) are used indistinctly. Their use will depend on the distance and transportation volume, topography, road conditions and available resources.

The cost of transportation when mechanized means are used ranges from 100 to 150 USD, that is, 50 to 75 USD / t of sugarcane. According to the statements of the respondents, 80% of the producers transports the sugarcane cut with labor animals or manually, only the remaining 20% transports the cane harvested with automotive means. The maximum transportation distances do not exceed 15 km for the case of automotive means, for animals from 0.5 to 2 km.

Type and State of Transportation Roads

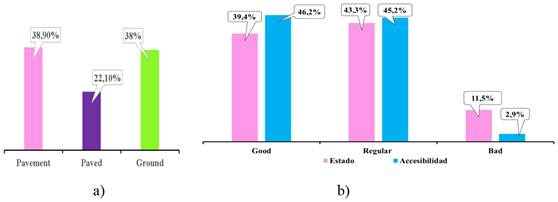

The analysis of the road type for access to the plantations or zones of location of the facilities for the sugarcane processing and its derivatives, showed that 60,2% of the roads are pavement (Asphalt) or are paved, only 38% is ground (Figure 7a).

According to the criteria of the technicians in charge of gathering information, only 11,5% of the roads are in poor conditions and 2.9% present serious accessibility problems (Figure 7b).

According to the criteria issued, it can be stated that the types of roads, their conditions, and accessibility to the cultivation and processing areas, do not constitute a limiting factor for the development of sugarcane, that is, in most parishes, there is an adequate infrastructure and network of roads, both for the transport of the raw material and for the commercialization of its derivatives, in the areas under study.

Training

Sugarcane growers of this area, who are part of the associations ASACAMA and IMPAGUA, participated in the school of sugarcane growers (ESCAM). In this school the training was developed within the framework of a project financed by the GPM. Very favorable criteria were collected on the quality and usefulness of this activity. However, this did not deal with aspects related to the use of machinery in the agrotechnical tasks demanded by sugarcane, producers were trained only on the use of machines for processing animal food and not to carry out agro-technical labor to the crop. Despite this, of the 151 producers surveyed, only 28% of them received the training, so it is of vital importance to continue working in this regard. Likewise, producers from the UTYPRAC and ASESAGRA associations were not trained.

CONCLUSIONS

Once the information obtained during the producers' surveys was analyzed, the following conclusions were reached:

The limiting factors for the mechanization of sugarcane in the cultivation areas of Manabí Province are related to the topography of the lands in the plantation zones (pending 50 to 70%), the limited availability of mechanized means, whether conventional or specialized, for the delivery of maximum slopes; insufficient training of technicians and producers in the management, administration and technical assistance of mechanized media; the roots of producers in the development of cultural practices that exclude the use of mechanized means and the high cost of renting these means.

The development of an adequate strategy for the mechanization of the production process of sugarcane and its derivatives, is the central axis for the increase of production and the strengthening of the productive chain in these areas.

The training of technicians and producers of these zones should be continued, as an essential element to achieve an attitude change, in relation to the use of mechanized means during soil preparation, cultural attention, transportation and benefit in sugarcane cultivation.

texto en

texto en