At present, the intake of food and the accelerated population growth have caused the increase in the cost of raw materials used in the formulation of balanced diets for monogastric animals. Because of this situation, as regards pigs, nutritionists have had to look for other sources of food that decrease the production cost, since this represents 70 % (Méndez et al. 2016). The use of alternative sources in pig feeding is a very suitable strategy, since it allows obtaining viable production systems that contribute to the environment conservation, and that do not compete directly with the human diet (Lezcano et al. 2014).

In the Republic of Ecuador, a great amount of alternative foods of vegetal origin is available, whose use is feasible for pig feeding, among which are the taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) tubers. Taro tubers are recognized as a good source of lower cost carbohydrates with respect to cereals such as corn, sorghum or wheat, and other types of roots and tubers (Caicedo et al.2015). In the elaboration of meals, in order to maintain their conservation, thermal processing such as drying can be applied, since these foods, due to their availability, in large volume and with little time of preservation, are not used in pig feeding adequately (Torres-Gallo et al. 2017).

The nutritional value of a ration, food or nutrient, can be expressed through its digestibility coefficient, which is the proportion of the food that is not excreted, and that is assumed to be absorbed. The digestibility coefficient is closely related to the nutritional value of food. In fact, the amount and type of excretion of fecal material in pigs depend on several factors, among which we can mention the age, the environment, the breed and the nature of diet. Therefore, it is essential to study the use of nutrients from diets to make balanced formulations for pigs feeding (Hossain et al. 2016). The above serves as a basis for determining the apparent digestibility of nutrients of taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) tubers meal in fattening pigs.

The study was carried out in the Programa de Porcinos de la Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA) from Republic of Ecuador. The temperature recorded during the study was 26 ºC and the average relative humidity was 90 %. Three castrated male pigs were used as experimental units, product of the commercial cross (Largewhite x Duroc x Pietrain), with an average live weight of 68 ± 2 kg. The animals were dewormed and randomly housed in metabolism cages of 1.0 m x 1.6 m (1.6 m2), located in a building with concrete walls and floor to facilitate cleaning (Zhang and Adeola 2017).

To prepare the meal, taro tubers were obtained in the rural parish "Teniente Hugo Ortiz", from Allishungo community, and moved to the study area. A solution with 3 % sodium hypochlorite in the water was prepared to wash the tubers for 10 min. Subsequently, they were rinsed and drained. Then, the chopped in slices and pre-drying in the sun for eight hours was carried. After drying, in an industrial rotary dryer (Burmester brand) at 70°C for two hours, it was immediately grounded in a semi-industrial mill (TRAPS brand, TRF 300G model) with a 0.25 mm mesh. The meal was packed in hermetic bags and stored until it was used. The chemical composition of meal was: 93.10 % dry matter (DM); 4.83% crude protein (CP), 93.5 % organic matter (OM), 6.50% crude fiber (CF), 4.67 % ash and 18.53 kJ g DM-1 of gross energy (GE).

The treatments consisted of three experimental diets (table 1): T1 (control diet based on corn and soybean); T2 and T3 (inclusion of 20 and 40 % of taro meal in the diet, respectively). All diets were fitted with 14 % crude protein and 17.84 kJ g DM-1 gross energy (Zanfi et al. 2014) and formulated according to the suggestions of the NRC (2012).

Table 1 Composition and contribution of experimental diets

1Each kg: contains: vitamin A, 4125 U.I.; vitamin D3, 900 U.I.; vitamin E, 24.8 UI; vitamin K3, 1.80 mg; vitamin B1, 0.60 mg; vitamin B2, 1.88 mg; pantothenic acid, 9 mg; nicotinic acid, 18 mg; fólic acid, 0.180 mg; vitamin B6, 1.20 mg; vitamin B12, 0.012 mg; biotin 0.060 mg; choline, 120mg; manganese, 64 mg; copper, 7.2 mg; iron, 48 mg; zinc, 66 mg; selenium, 0.22 mg; iodine, 0.60 mg.

The experiment lasted 27 d, distributed in three periods. Each one had duration of 9 d, five of adaptation to the diets and four of feces collection. The feces were collected by the method of total collection in the early hours of the morning 8:00 am (Ly et al.2013). At the beginning of the experiment, the animals were weighed to fit the food intake, at a rate of 0.10 kg (kg/DM) LW0.75 d-1. The food was supplied in two parts: 8:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Throughout the experiment, the pigs had free access to water (Ly et al. 2014a).

From each animal, a representative sample of 100 g of fresh excreta/d was collected, which was stored in freezing at -20 °C. The calculation of fecal output of materials was performed according to Ly et al. (2009). In addition, the digestibility of the diet (100 - % digestibility) was taken into account.

In the food samples and excreta the DM, CF, ashes and CP (N x 6.25) were determined, according to the AOAC (2005) procedures. It was considered that the OM content was the result of subtracting 100 percent of ash. The analyzes were carried out in the Laboratorio de Química, de la Universidad Estatal Amazónica, Ecuador. For each nutrient, the analyzes were performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance was performed and the Duncan (1955) test was applied with the statistical program Infostat (Di Rienzo et al. 2012).

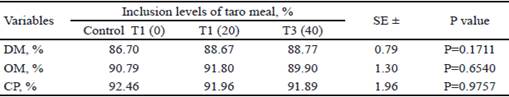

As the days passed, the food was totally intake, with no rejection sign. The apparent digestibility coefficients of DM, OM and CP in pigs (Largewhite x Duroc x Pietrain) fed with taro tuberous meal in the fattening stage were high (table 2). There were no significant differences (P> 0.05) for the use of DM: T1 (86.70 %); T2 (88.67 %); T3 (88.77 %), OM (T1: 90.79 %); T2 (91.80 %); T3 (89.90 %) and CP: T1 (92.46 %); T2 (91.96 %) and T3 (91.89 %).

Table 2 Coefficients of apparent rectal digestibility of DM, OM and CP in fattening pigs diets, fed with taro tubers meal

There are no significant differences P> 0.05 according to Duncan (1995)

The apparent digestibility coefficients of the DM, OM and CP in fattening pig diets, which included high levels of taro rejection tubers meal, were high. This could be due to the process of chopping, drying and milling that the tubers received. For the proper use of products and byproducts of vegetable origin, different processes must be carried out, such as fermentation, cooking and drying, to optimize the use of these foods (López et al. 2006).

The application of these techniques allows reducing or eliminating the content of secondary metabolites of tubers and, consequently, improvements in the use of nutrients for pigs are obtained (Caicedo et al. 2017). On the other hand, when these foods are supplied in a natural state, they have high content of secondary metabolites, which can cause a severe irritation in the membranes of the intestinal mucosa, inhibition of digestion and absorption of proteins, which consequently affects the normal growth of animals (Martens et al. 2014).

Ly and Delgado (2005) confirm the above, when evaluating the rectal digestibility of DM and OM in pigs fed with dry taro tubers and in their natural state. These authors reported higher apparent digestibility coefficients for DM (66.90 %) and OM (76 %) in dry tubers, with respect to natural state tubers DM (31.50 %) and OM (38.30 %), respectively. Likewise, in another study on apparent rectal digestibility in pigs fed cassava root in natural state, Ly et al. (2010) obtained utilization coefficients of DM 66 % and OM of 68.7 %, figures lower than those referred in this study.

Ly et al. (2014b) state that from the point of view of the rectal digestibility of nutrients in roots and tubers, utilization coefficients higher than 85 % are obtained, when they undergo some thermal processing, when compared with tubers in their natural state, which was evident in this study. This state is equivalent to what is obtained with the productive performance traits of pigs (Caicedo 2015).

Torres et al. (2013) point out that taro tubers have a very small starch, about 5 μm, and have lateral branches (amylopectin). This favors the fluidity of water through the internal spaces of the polymers of the starch and benefits its solubility. When the starch granules hydrate, they cause an increase in their size and change their semicrystalline structure to amorphous, a process known as gelatinization. This change in structure provides higher starch digestibility due to the action of amylases, generated in the salivary and pancreatic glands of pigs (Lapis et al. 2017).

The rectal digestibility of the DM, OM and CP showed high utilization rates, when including 20 and 40 % of taro tuberous meal in the diet, which guarantees a food with adequate nutritional characteristics for fattening pigs.

texto en

texto en