Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Cultivos Tropicales

versión impresa ISSN 0258-5936versión On-line ISSN 1819-4087

cultrop vol.42 no.4 La Habana oct.-dic. 2021 Epub 30-Dic-2021

Original article

Participatory selection of bean cultivars (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Los Palacios, Pinar del Río

1Unidad Científico Tecnológica de Base “Los Palacios”, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA). Carretera La Francia km 1½, Los Palacios, Pinar del Río, Cuba. CP 22 900

The introduction of inclusive methodologies, such as Participatory Cultivar Selection, has shown that more decentralized policies support the increase of genetic diversity in crops, strengthen producers' knowledge and recognition as protagonists in agricultural innovation, which contributes to accelerate the adoption rate and increase production. The aim of the study was to identify cultivars with the greatest acceptance and the agronomic criteria of greatest consideration from participants’ perspective. The participatory selection was carried out at the Agrodiversity Fair in a farm belonging to the “Menelao Mora” Cooperative in Los Palacios municipality, where producers, technicians and decision-makers of both sexes participated. The effective diversity percentage was determined, cultivars with the greatest acceptance and the most relevant agronomic criteria were identified. Female participation reached 39 % and effective diversity was 100 %. Milagro villaclareño, Tomeguín 93, Chévere, Quivicán, Delicias 364 and Tradicional Codorniz cultivars stood out for their good performance for the locality; the characters with the highest degree of acceptance at the time of selection were number of pods per plant, number of grains per pod, grain color and plant size. The results suggest that fairs constitute an alternative to provide diversity in bean production, as one of the strategies to face climatic variation in the current context.

Key words: selection criteria; yield; bean; cooperative; fair

INTRODUCTION

The common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is a very important grain legume in the Americas and part of Africa, where it serves as a vital source of protein, vitamins and mineral nutrients 1 and it is the third most important legume for human consumption worldwide after soybeans and peanuts. However, bean production level in Latin America is relatively low, and in Cuba the situation is similar because the expected harvest results are not achieved, due to various factors that affect crop productivity, including drastic changes in climate, the scarce availability of quality seeds, the presence of pests and diseases, low water availability and nutrient deficiency in soils, as well as high input prices 2,3.

National production satisfies only 3 % of the consumption demand of Cubans, so it is necessary to import about 110,000 tons of grain each year 4. For this reason, among the priorities of Cuban agriculture is to increase the production of this crop, allocating large extensions of land in the state sector, as well as in the cooperative and peasant sectors, with strategies and technologies that are environmentally friendly, the breeding of cultivars, increased production of seeds, etc.

To this end, it is necessary to have cultivars that are better adapted to the different agroecosystems in which this legume is grown 5. For this process, the “Agrodiversity Fairs” have been very successful, a methodology that has contributed to the introduction of new technologies and new diversity of different crops to farmers' farms 6-10. These Fairs have become an effective alternative to facilitate the flow of seeds from the Research Institute to the farmer and vice versa; they constitute a supply of genetic diversity with great community acceptance and a broad spectrum of demand by farmers. In addition, it is a complement to the genetic breeding programs that are developed with numerous species of agricultural crops, in such a way that through the participatory selection of new genetic materials, it is possible to minimize the time required for the extension of new cultivars, as well as to select them in a more effective way for each specific condition.

Participatory Variety Selection (PVS) has become a motivating force in agricultural research and rural development. This approach makes it possible to consider the agroecological conditions and cultural practices of the target zones; the local knowledge and producer preferences in these zones; as well as the preferences and requirements of the other stake holders in the productive chain. Programs in several countries have demonstrated this method effectiveness 11-18. In Cuba, it has been successfully used in crops such as rice, beans, tomatoes, cassava and chickpeas, among others 6-9,19.

Considering this background, the main aim of this study is to identify cultivars with greater acceptance and the agronomic criteria of greater consideration from the participants´ perspective in the PVS of beans in conditions of Los Palacios municipality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General aspects for the assembly of cultivar garden

Bean Cultivar Garden for the Agrodiversity Fair development was located in the farm of the producer Jesús Rivera, belonging to the Credit and Service Cooperative (CCS) “Menelao Mora” in Los Palacios municipality, Pinar del Río province. An area was selected for the adequate establishment of cultivars. For the assembly of plots, the uniformity of soil was sought to avoid differences between cultivars due to factors unrelated to the characteristics of each one of them. The cropping practices carried out during the crop cycle (soil preparation, sowing, fertilization, irrigation and phytosanitary treatments) were carried out as recommended by the Technical Guide for the Common Beans and Corn Production 20. Cultivars were planted in furrows 3 m long, plots consisted of five furrows and a minimum space was left between them to avoid the possible effect of competition between cultivars.

Nineteen cultivars (17 from the National Breeding Program for this crop and 2 traditional cultivars planted in the territory) were put to the consideration of participants, which were identified with a consecutive number and not with their real name. The name and origin of each cultivar are informed after the selection is made so that it does not influence the participants during this process, as this could sometimes bias the results. Cultivars submitted for evaluation and some of their characteristics are listed (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of bean cultivars exhibited at the fair

| No. | Cultivar | Characteristics | Grain color |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CC-25-9 | Long cycle, high yield potential and consumption preference (more than 2 t ha-1). | Black |

| 2 | BAT 304 | Short cycle, high yield potential | Black |

| 3 | TAZUMAL | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | Black |

| 4 | Tomeguín 93 | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | Black |

| 5 | CUL 156 | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | Black |

| 6 | Liliana | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | Black |

| 7 | Cubana 23 | Medium cycle, medium yield potential | Black |

| 8 | Milagro Villareño | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Black |

| 9 | CUFIG 48 | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | Black |

| 10 | Delicias 364 | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Red |

| 11 | Buenaventura | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Red |

| 12 | CUFIG 110 | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Red |

| 13 | La Cuba 154 | Medium cycle, high yield potential and architecture for mechanized harvesting. | White |

| 14 | Chévere | Medium cycle, high yield potential | White |

| 15 | Engañador | Medium cycle, high yield potential | White |

| 16 | Quivicán | Medium cycle, high yield potential | White |

| 17 | CUFIG 145 | Medium cycle, high yield potential | White |

| 18 | Tradicional Codorniz* | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Black |

| 19 | Tradicional 1* | Medium cycle, high yield potential | Black |

*Cultivars traditionally sown in the territory

Surveys for the PVS

The methodology for the SPV was explained and the completed surveys were handed out, containing different criteria for the selection of these criteria, with a space for the participants to add any other data they considered important to take into account (Figure 1).

Participants

Producers from Los Palacios municipality participated, both from the State Sector, mainly linked to the Agroindustrial Grain Enterprise. (EAIG, according its acronyms in Spanish), as well as from the Cooperative and Peasant Sector, belonging to different productive forms (Credit and Service Cooperatives and Agricultural Production Cooperatives). In addition, specialists, technicians, researchers and decision-makers from the territory.

Experience Exchange

As part of the Agrodiversity Fair, a talk was given on “Bean cultivation and characteristics of the cultivars proposed by the National Breeding Program”. Aspects related to the management of the crop and its technology were also discussed; results of trials carried out under experimental conditions on the response of a cultivar group, including those presented, were discussed. Participants had the opportunity to exchange experiences and discuss criteria among producers and between them and UCTB researchers, decision makers from the Municipal Delegation of Agriculture and the Agroindustrial Grain Enterprise.

Information analysis

For the data compilation, the list of participants was used, in which were registered: name, sex, occupation, place of origin, work center or productive unit, address and telephone number, as well as the surveys prepared for this purpose, where both the selected cultivars and the selection criteria appeared, based on the visual observation of the integral behavior of cultivars. Descriptive statistics were used for the indicators evaluated, by counting and summing the number of votes cast for each one, in order to know the cultivars of greatest interest to the participants and likewise for the most important selection criteria.

The tabulation of all the information was carried out using Microsoft Excel 2016. At the time of analyzing the information, specialists, technicians, researchers and extensionists were included in the category of “technicians”.

To measure the selection efficiency, the effective diversity percentage of (% ED) was calculated using the formula:

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Twenty-eight people participated in the selection of bean cultivars at the Agrodiversity Fair (Table 2), which corresponds to the number of participants/fair reported in participation studies recorded in more than 200 Agrodiversity Fairs of different crops held in various provinces of Cuba 21. The Local Agricultural Innovation Program (PIAL, according its acronyms in Spanish) has supported the holding of more than 680 fairs in the country in which more than 19 500 producers from 97 localities corresponding to 45 municipalities in 10 provinces have participated. These fairs have facilitated the creation of a broad solidarity network of farmers for the environmental, social and economic benefit of productive units, with a strong impact on the availability and autonomy of seeds and on food security and sovereignty at the community level 22.

Table 2 Number of participants per group in the participatory selection of bean cultivars

| Groups | Women and men | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productors | 16 | 57 | ||

| Technicians | 7 | 25 | ||

| Decision-makers | 5 | 18 | ||

| Total | 28 | 100 | ||

| 11 W | 17 M | 39 W | 61 M | |

W: Women, M: Men

Female participation reached 39 %, which demonstrates the growing incorporation of women in agricultural activities, although it is recognized that there is still a need to increase the presence of women in the sector, based on the gender approach application in local development. This is even more relevant if it takes into account that many women are responsible for the production, purchase, processing and preparation of most of the food consumed. However, women in vulnerable conditions often have limited access to nutritional information and the necessary resources (income, land, technology, services and others) to improve food security 23. Other authors studying the meaning and repercussion of these Fairs in Cuba have observed a favorable development in terms of equity in the peasant family, although the aspect of women leaders in organizations still needs to be improved, although they recognize that it is significantly higher than at the beginning of the PIAL 22.

It is known that women and men have different tasks in the home and on the farm, as well as different roles and responsibilities with respect to resource management; women play a fundamental role in plant identification and introduction, and have extensive and detailed knowledge about food, fodder, and medicines. Smallholder women farmers are active in the breeding, selection, management, processing, storage and conservation of plant resources. Globally, women are the main doers involved in smallholder seed selection and storage and in farmer-to-farmer seed distribution networks 24.

Also on display, as an initiative of the women, were products made by them (canned food, handicrafts, articles made from recycled disposable materials, still-life arrangements and other handicrafts (weaving, sewing, etc.). There was also an exchange of experiences and it was recognized that these actions contribute to the rescue of traditions and in some cases constitute sources of income for women. When women are socially and economically empowered, they can become a powerful force for change. In rural areas of the developing world, women play a crucial role in household management and their contribution to agricultural production is fundamental. However, inequalities between women and men hinder women's full realization 25.

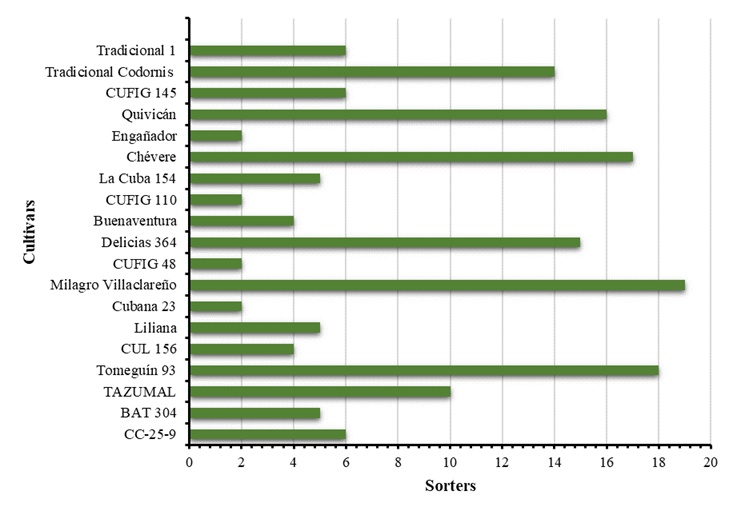

The fair presented a wide varietal diversity with the presence of black (58 %), white (26 %) and red (16 %) beans. Participants had the opportunity to appreciate in situ the characteristics and behavior of different cultivars on display, select the five of their preference and, in the case of producers, take them to their farms to evaluate them under their own production conditions. Figure 2 shows results of bean cultivar participatory selection, the most preferred were: Milagro villaclareño, Tomeguín 93, Chévere, Quivicán, Delicias 364 and Tradicional Codorniz. This indicates a good performance of the new materials under these conditions.

In this regard, it is important to note that Tradicional Codorniz cultivar surpass 13 of the proposed cultivars, while in the case of Tradicional 1 it surpass 9 cultivars. This aspect is influenced by the selection made by producers in a rudimentary and almost unconscious way, which has generated the existence of many locally adapted cultivars used in the cooperative and peasant sector. In this regard, breeders and cultivar release committees are increasingly recognizing that the model of a “widely adapted single super variety” is often incompatible with the real needs of small farmers, which depend on climate, use, seasonality, etc. In crop management, there is no “one unique model for all” 26.

The inclusion of local cultivars in the fair allowed producers to compare these with those proposed and to recognize those with desirable traits and good behavior. This strategy favors the conservation of traditional cultivars in the localities and thus reduces the risk of genetic erosion.

Figure 2 Cultivars selected by participants in the Agrodiversity Fair of beans in Los Palacios municipality

All cultivars were selected by more than one person and in the case of Milagro villaclareño, Tomeguín 93, Chévere, Quivicán and Delicias 364, they reached 68, 64, 61, 57 and 53 %, respectively; black (2) and white (2) cultivars were equally represented, while red (1) was the least, followed by the cultivar Tradicional Codorniz with 50 %. The effective diversity was 100 %, which confirms good adaptation to local edaphoclimatic conditions and great acceptance of the materials exhibited at the fair. It is suggested that the percentage of selection or effective diversity may be related to the variability shown by the species under study, since in a species with greater variability, local materials may be more important than in species with less variability 8.

In bean fairs held in Havana and La Palma, the average number of cultivars per farmer was 4.98 and 4.81, respectively. These averages were considered high, since a maximum limit of up to five varieties per farmer had been established as in this study, which reflects their interest in selecting and testing new cultivars, and indicates that perhaps the farmers should have been left to decide how many to select, which would probably have contributed to the introduction of a greater number of cultivars in the communities 27.

In recent years, research centers and mainly plant breeders have paid more attention to the priorities of farmers in order to improve access to the materials generated. Breeding strategies and cultivar extensionism have great scope, since they make it possible to respond to the current challenges of agriculture. In this sense, participatory plant breeding has evolved as a viable alternative to conventional plant breeding, which places greater emphasis on the participation of different stakeholders from the choice of varietal specifications, selection of parents to selection in segregating generations, as well as testing and product release. Greater involvement of farmers and other stakeholders ensures that their perceptions are addressed to accelerate the adoption rate 28. In addition, producers show a high capacity for work and real commitment to improving the agricultural situation, which makes it possible to scale higher levels of cooperation, articulation and the establishment of synergies in the management of territorial and national agricultural development 29.

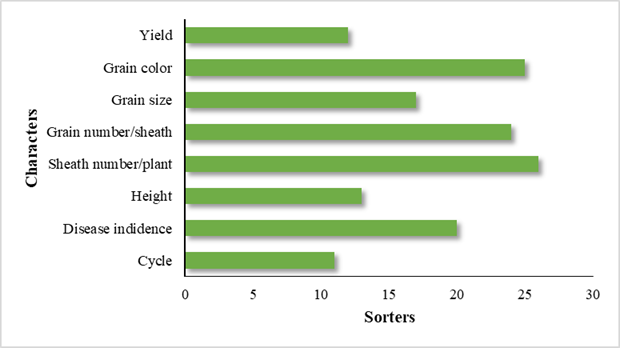

Figure 3 shows survey results on the selection criteria. It can be seen that the characters of greatest consideration at the time of cultivar selection were: number of pods per plant, number of grains per pod, grain color and plant size. In a similar PVS study in Cuba for outstanding genotype identification of common bean, it is reported that the selective criteria with which diversity was related were high yield, resistance to common Bacteriosis and bean color 8.

On the other hand, the high contribution of the trait number of pods per plant to bean crop yield is known 30. Research has reported that with an average of eight pods per plant and a stocking density of 250 000 effective plants per hectare, yields of more than 1500 kg ha-1 can be obtained, which will be related to bean mass and the number of beans per pod. However, as there are other influencing factors, a number of pods lower than 10 is considered low, even though this depends on the conditions in which each cultivar develops 31.

Figure 3 Selection criteria by participants in the Agrodiversity Fair of beans in Los Palacios municipality

In similar PVS-based work in western Kenya, preference analysis was based on four important characteristics: bean yield, maturity duration, disease reaction, and bean color acceptability. The exercise provided farmers with a structured questionnaire to make their choice for further analysis, which allowed the identification of preferred bean varieties 32.

Some authors have also analyzed farmers' evaluation of varietal characteristics in beans, and reported that farmers judge bean cultivars on yield, early maturity and bean color, both in intercropping and under adverse conditions. While in other cases the choice of cultivars is governed mainly by bean color, cooking time, flavor, bean size and brightness 33,34.

Plant breeding influences individuals and societies because it determines the course of the agricultural future. Without cultivars appropriate to particular farming systems, farmers cannot succeed and consumers suffer from price increases or lack of food availability or both. Participatory Plant Breeding is a useful methodology, which has enabled breeders and farmers in the developing world to create cultivars adapted to the adverse conditions of many livelihood farms. This is achieved by taking advantage of genotype-environment interaction and selecting cultivars directly in the intended environment to achieve superior performance. Farmer participation is a crucial aspect of the methodology, as the farmer is better equipped to recognize the agronomic and quality traits that will enable the cultivar to be productive in his or her system 35. This methodology has been widely used in bean cultivation because of the advantages it brings 8,26,27,36,37.

The fair also proved to be a space for training, exchange of experiences and horizontal interaction among producers, technicians and other key doers.

CONCLUSIONS

The genotypes with good performance for Los Palacios according to the participatory selection were Milagro villaclareño (68 %), Tomeguín 93 (64 %), Chévere (61 %), Quivicán (57 %), Delicias 364 (53 %) and Tradicional Codorniz (50 %), with a high level of adaptation under these conditions and greater probability of being adopted.

The characters number of pods per plant, number of beans per pod, bean color and plant size were the most important in the participatory selection of bean cultivars.

The Agrodiversity Fair constituted an alternative to provide diversity in bean production, as one of the strategies to face climate variation in the current context; it was also an excellent space for training in order to dynamize and strengthen the learning process and interaction of various doers, as well as to promote gender equity and the empowerment of Cuban women.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

1. Dorcinvil R, Sotomayor-Ramírez D, Beaver J. Agronomic performance of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) lines in an Oxisol. Field Crops Research. 2010;118(3):264-72. [ Links ]

2. Rivera Espinosa R, Fundora Sánchez LR, Calderón Puig A, Martín Cárdenas JV, Marrero Cruz Y, Ruiz Martínez L, et al. La efectividad del biofertilizante EcoMic(r) en el cultivo de la yuca. Resultados de las campañas de extensiones con productores. Cultivos Tropicales. 2012;33(1):5-10. [ Links ]

3. González LM. Efecto de productos bioactivos en plantas de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) biofertilizadas. Cultivos Tropicales. 2016;37(3):165-71. [ Links ]

4. Garra AS, Pequeño MR, de la Cruz Martín S. El uso de biofertilizantes en el cultivo del frijol: una alternativa para la agricultura sostenible en Sagua la Grande. Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana. 2011;(159). [ Links ]

5. Pedroza-Sandoval A, Trejo-Calzada R, Sánchez-Cohen I, Samaniego-Gaxiola JA, Yáñez-Chávez LG. Evaluación de tres variedades de frijol pinto bajo riego y sequía en Durango, México. Agronomía Mesoamericana. 2016;27(1):167-76. [ Links ]

6. Moya-López CC, Orozco-Crespo E, Mesa-Fleitas ME. Ferias de agro-biodiversidad cubanas: vía para la selección de variedades de tomate. Agronomía Mesoamericana. 2016;27(2):301-10. [ Links ]

7. Cárdenas Travieso RM, de la Fé Montenegro CF, Echevarría Hernández A, Ortiz Pérez R, Lamz Piedra A. Selección participativa de cultivares de garbanzo (Cicer arietinum L.) en feria de diversidad de San Antonio de los Baños, Artemisa, Cuba. Cultivos Tropicales. 2016;37(2):134-40. [ Links ]

8. Lamz Piedra A, Cárdenas Travieso RM, Ortiz Pérez R, Hernandez Gallardo Y, Alfonso Duque LE. Efecto de la selección participativa de variedades en la identificación de genotipos sobresalientes de frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Centro Agrícola. 2017;44(4):65-74. [ Links ]

9. Álvarez-Kile PM, Rodríguez-Montes W. Evaluación de 7 variedades de yuca mediante una feria de biodiversidad en condiciones de sequía en el municipio Jiguaní. Redel. Revista Granmense de Desarrollo Local. 2018;2(1):80-9. [ Links ]

10. Díaz-Solis SH, Morejón-Rivera R, Maqueira-López LA, Echevarría-Hernández A, Cruz-Triana A, Roján-Herrera O. Selección participativa de cultivares de soya (Glycine max L.) en Los Palacios, Pinar del Río, Cuba. Cultivos Tropicales. 2019;40(4). [ Links ]

11. Mudege NN, Mukewa E, Amele A. Workshop report: training on gender integrated potato participatory varietal selection (pvs) in Ethiopia. 2015; [ Links ]

12. Getahun A, Atnaf M, Abady S, Degu T, Dilnesaw Z. Participatory variety selection of soybean Glycine max(L.) Merrill) varieties under rain fed condition of Pawe district, north-western Ethiopia. International Journal of Applied Science and Mathematics. 2016;3(1):40-3. [ Links ]

13. Horn LN, Ghebrehiwot HM, Sarsu F, Shimelis AH. Participatory varietal selection among elite cowpea genotypes in northern Namibia. Legume Research-An International Journal. 2017;40(6):995-1003. [ Links ]

14. Goa Y, Ashamo M. Participatory approaches for varietal improvement, it's significances and challenges in Ethiopia and some other countries: A Review. International Journal of Research Studies in Science, Engineering and Technology [IJRSSET]. 2017;4(1):25-40. [ Links ]

15. Diouf M, Gueye M, Samb PI. Participatory varietal selection and agronomic evaluation of African eggplant and Roselle varieties in Mali. European Scientific Journal, ESJ. 2017;13(30):327-40. [ Links ]

16. Sugiharto AN, Andajani TK, Baladina N. Effectiveness of participatory varietal selection in corn cultivar establishment. Journal of Advanced Agricultural Technologies. 2017;4(4). [ Links ]

17. Wilkus EL, Francesconi GN, Jäger M. Rural seed sector development through participatory varietal selection: Synergies and trade-offs in seed provision services and market participation among household bean producers in Western Uganda. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies. 2017; [ Links ]

18. Hunde D, Tefera G. Participatory varietal selection and evaluation of twelve soybeans Glycine max (L.) Merrill] varieties for lowland areas of North Western Ethiopia. International Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Science. 2018;5(2):403. [ Links ]

19. Morejón R, Díaz SH, Díaz GS, Pérez N, Ipsán Pedrera D. Algunos aspectos del manejo de la semilla de arroz por productores del sector cooperativo campesino en dos localidades de Pinar del Río. Cultivos Tropicales. 2014;35(2):80-5. [ Links ]

20. Faure Alvarez B, Bentez Gonzÿlez R. Guía técnica para la producción de frijol común y maíz. Artemisa, Cuba: Instituto de Investigaciones en Granos; 2014. [ Links ]

21. Ortiz Pérez R, Angarica L, Guevara-Hernández F. Beneficios obtenidos en fincas participantes en el Programa de Innovación Agropecuaria Local (PIAL) en Cuba. Análisis costo/beneficio de la intervención. Cultivos tropicales. 2014;35(3):107-12. [ Links ]

22. Ortíz Pérez R, Miranda Lorigados S, Rodríguez Miranda O, Gil Díaz V, Márquez Serrano M, Guevara Hernández F. Las ferias de agrodiversidad en el contexto del fitomejoramiento participativo-programa de innovación agropecuaria local en Cuba. Significado y repercusión. Cultivos Tropicales. 2015;36(3):124-32. [ Links ]

23. Polar V, Babini C, Flores P. Tecnología para hombres y mujeres: Recomendaciones para reforzar la temática de género en procesos de innovación tecnológica agrícola para la seguridad alimentaria. La Paz, Bolivia: International Potato Center; 2015. 48 p. [ Links ]

24. Elias M. The importance of gender in agricultural research. In: Strengthening the role of custodian farmers in the national conservation programme of Nepal: proceedings from the national workshop: 31 July to 2 August 20. Pokhara, Nepal: Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research and Development (Li-Bird); 2015. p. 186. [ Links ]

25. FIDA. La mujer y el desarrollo rural. Dar a la población rural pobre la oportunidad de salir de la pobreza. Roma, Italia: Fondo Internacional de Desarrollo Agrícola; 2018 p. 4. [ Links ]

26. Haan S de, Salas E, Fonseca C, Gastelo M, Amaya N, Bastos C, et al. Selección participativa de variedades de papa (SPV) usando el diseño mamá y bebé: una guía para capacitadores con perspectiva de género. Lima-Perú: International Potato Center; 2017. 82 p. [ Links ]

27. Miranda S, Ortiz R, Ponce M, Acosta R, Ríos H. La selección participativa de variedades de frijol común por agricultores en ferias de diversidad: una alternativa para la introducción de variedades. Cultivos Tropicales. 2007;28(4):57-65. [ Links ]

28. Sheikh AA, Jabeen N, Sheikh AA, Yousuf N, Nabi SU, Bhat TA, et al. Evaluation of french bean germplasm based on farmer specified attributes through participatory varietal selection (pvs) in Kashmir valley. Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2017;5(2):585-94. [ Links ]

29. Ortiz R, Acosta R, Angarica L, Guevara F. Diagnóstico del contexto y seguimiento de cambios de actitud para acciones efectivas de un proyecto de innovación agropecuaria. Cultivos Tropicales. 2017;38(2):84-93. [ Links ]

30. Zilio M, Coelho CMM, Souza CA, Santos JCP, Miquelluti DJ. Contribuição dos componentes de rendimento na produtividade de genótipos crioulos de feijão (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Revista Ciência Agronômica. 2011;42(2):429-38. [ Links ]

31. de la Fé Montenegro CF, Lamz Piedra A, Cárdenas Travieso RM, Hernández Pérez J. Respuesta agronómica de cultivares de frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) de reciente introducción en Cuba. Cultivos Tropicales. 2016;37(2):102-7. [ Links ]

32. Yadavendra JP, Gadade O, Dash S. Scaling niche specific common beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) varieties based on participatory varietal selection in western Kenya. International Journal of Pure of Applied Biosciences. 2017;5:1161-9. [ Links ]

33. Chirwa R, Phiri M a. R. Factors that influence demand for beans in Malawi [Internet]. International Center for Tropical Agriculture; 2006 [cited 07/08/2021]. Available from: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/72302 [ Links ]

34. Collinson MP. A history of farming systems research [Internet]. Rome, Italy; New York: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations?; CABI Pub.; 2000 [cited 07/08/2021]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851994055.0000 [ Links ]

35. Shelton AC, Tracy WF, Kapuscinski AR, Locke KA. Participatory plant breeding and organic agriculture: A synergistic model for organic variety development in the United States. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2016;4(000143). [ Links ]

36. Balcha A, Tigabu R. Participatory varietal selection of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Wolaita, Ethiopia. Asian journal of crop science. 2015;7(4):295. [ Links ]

37. Bruno A, Katungi E, Stanley NT, Clare M, Maxwell MG, Paul G, et al. Participatory farmers' selection of common bean varieties (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under different production constraints. Plant Breeding. 2018;137(3):283-9. [ Links ]

Received: October 30, 2019; Accepted: June 16, 2021

texto en

texto en