My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

ACIMED

Print version ISSN 1024-9435

ACIMED vol.20 no.6 Ciudad de La Habana Dec. 2009

ARTÍCULOS

A socio-psycholinguistic model for English for specific purposes writing skill formation diagnosis

Modelo socio-psicolingüístico para el diagnóstico de la habilidad expresión escrita en la enseñanza del inglés con fines específicos

Rafael Forteza Fernández,I Paul GunashekarII

IDoctor in Pedagogical Sciences. Associate Professor of Research Methodology and English. Facultad de Enfermería. Universidad Médica "Mariana Grajales Coello". Holguín, Cuba.

IIHead. Department of Materials Development, Testing and Evaluation. The English and Foreign Languages University Hyderabad, India.

ABSTRACT

The teaching learning process of writing in English for Specific Purposes is influenced by factors which go beyond the environment of the classroom. These factors, identified as variables, have sociolinguistic, psychological and didactic nature. The present study uncovers some of the most outstanding variables and presents a new model for the continued diagnostic testing in the formation of writing skill in academic settings. The model is presented in variables which form new dimensions while testing takes place in loops, all of which giving rise to new regularities for this type of pedagogical activity.

Key words: English for specific purposes, diagnostic testing, academic settings.

RESUMEN

El proceso enseñanza-aprendizaje de la escritura en el inglés con fines específicos está influenciado por factores que van más allá del ambiente del aula. Estos factores, identificados como variables, son de naturaleza sociolingüística, psicológica y didáctica. El estudio revela algunas de las más importantes de estas variables y presenta un modelo para pruebas diagnósticas continuas de la formación de esta habilidad en contextos académicos. El modelo se presenta en variables que dan lugar a nuevas dimensiones mientras el diagnóstico se realiza en forma de eslabones, todo lo cual origina nuevas regularidades en este tipo de actividad pedagógica.

Palabras clave: Inglés con fines específicos, pruebas diagnósticas, contextos académicos.

Recent world events have underscored the need to increase understanding and to improve communication among all citizens. An international exchange of ideas is essential in areas ranging from the environmentglobal warming and the thinning ozone layer-to medical research-genetic engineering and equitable distribution of modern drug therapies-to the political challenges of a global economy. To meet these communication needs, more and more individuals have highly specific academic and professional reasons for seeking to improve their language skills. For these students, usually adults, courses that fall under the heading English for special purposes (ESP) hold particular appeal.

Most ESP courses form an important language provision for Non-native speakers (NNS) studying at English-speaking universities. ESP courses can either be `pre-sessional', where students take the course before they go on to further academic study, or `in-sessional', where students study whilst already on an academic course. A second distinction in course type is between `subject-specific ESP' and `common-core ESP', "… if it is common-core it will be concerned with general academic language and will focus on study skills; if it is subject-specific it will examine the language features of particular academic disciplines or subjects, e.g. social sciences or economics".1

The primary purpose, however, of all ESP courses is the same. It is to equip NNS with the language and study skills needed so that they may successfully follow their field of academic study. Traditionally this has meant a syllabus defined primarily in terms of `discourse functions' such as `cause and effect', `description', `narrative', `process' etc. and delivered through skills classes such as `academic writing, speaking, listening and reading'. Writing, in particular, helps these students to insert themselves successfully in their corresponding academic discourse communities. Project work and study skills usually form additional elements to most courses.

Writing skill formation is a well-establish paradigm in contemporary foreign language teaching methodology. Two distinct approaches have historically characterised the efforts to develop the skill to write in a foreign code. The first, the product approach, focuses on the forms of the language; and the second, the process approach, focuses on the necessary stages to transform thought into written language. Nevertheless, neither of these has been able to cope with producing competent writers.

Focusing solely in the structures of the language, either mother tongue (L1) or foreign language (L2), the product approach to teaching writing has its origins in behaviourist psychology and structural linguistics, out of which it takes its preoccupation for constant modelling and repetition of structures at sentence, paragraph and composition level writing. Correctness is the fundamental aim in learning how to write. Other aspects of writing such as the text's fulfilment of social constraints and communicative purpose(s) as well as the necessary processes for the transformation of thought into written language are neglected.

In the 1960s, cognitive psychology studies of competent writers' processes for the transformation of thought into written language brought about what today is known as process writing. This approach focuses on the necessary steps to produce a text. These steps extend from generating ideas, composing drafts, and revising to editing and proofreading. The process approach pays no attention to the forms of the language, and the student usually produces writing pieces with very rich in ideas, but with no sense of accuracy due mainly to little or no revising or lack of knowledge to do so.2

The situation turns more difficult when the formation of writing skills is related to the production of professional or academic texts. The nature of academic and professional literacy often confuses and disorients students, particularly those who bring with them a set of conventions that are at odds with those of the academic world they are entering. In addition, the culture-specific nature of schemata —abstract mental structures representing our knowledge of things, events, and situations— can lead to difficulties when students write texts in L2. Knowing how to write a "summary" or "analysis" in Mandarin or Spanish does not necessarily mean that students will be able to do these things in English.3

In reference to academic writing, since the mid-1980s, considerable attention has been paid to the genre approach to teaching writing. In terms of writing in a second [or foreign] language, The Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning defines the genre approach as a framework for language instruction based on examples of a particular genre. A genre is "a recognizable communicative event characterized by a set of communicative purpose(s) identified and mutually understood by the members of the professional or academic community in which it regularly occurs… [a genre is] often highly structured and conventionalized with constraints on allowable contributions in terms of their intent, positioning, form and functional value".4

Language, then, in a genre perspective, is both purposeful and inseparable from the social and cultural context in which it occurs. The goals and objectives of genre-based approach pedagogy are to enable learners to use genres which are important for them to be able to participate in, and have access to a particular discourse community. In other words, it incorporates relevant aspects of text production: awareness of the social and cultural context and meaningful learning. In addition, it takes into consideration the essential steps to produce a written professional text with the necessary degree of correctness.

Contrary to efforts in developing new ways to approach the issue of teaching how to write in the second or foreign language, diagnostic testing has not evolved in the same direction. Reports state that several studies have looked at lecturers' views on ESL students' writing or academic literacy skills; other studies have examined lecturers' reactions to and tolerance of errors in grammar and English usage. For example, the lecturers interviewed studied identified several `weaknesses' that contributed to `academic illiteracy' including: limited disciplinary vocabulary, inability to provide relevant examples connected to the concepts; and lack of objectivity.5

Hitherto ESP diagnostic testing foundations are still behaviorist and structural. Any piece of writing in assessed in terms of the forms of the language coherence, cohesion, grammar, vocabulary, mechanics and punctuation. This assessment is generally based upon a fixed set of indicators which tell nothing of the student's progress in learning, except the system of the language. Other aspects such as writing processes, choice of a correct strategy for writing, influence of the mother tongue, the social constraints of the text, and the student's cognitive and motivational state are never considered. Writing is always a product. Therefore, the information obtained out of testing is of little or no value for feedback as the means to correct both teaching and learning. 6

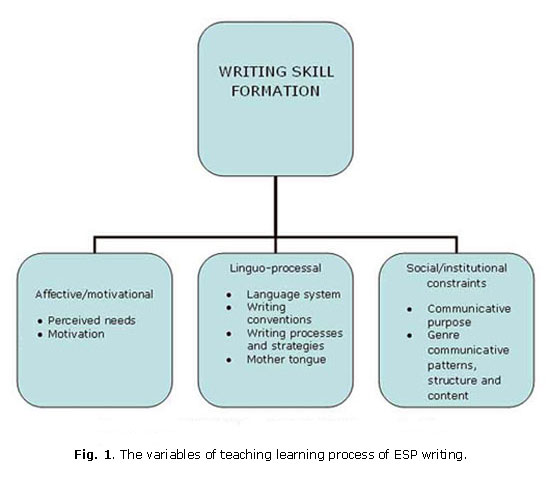

The fact is that the writing teaching-learning process is influenced by several variables which, holistically seen, comprise social, linguo-procesal, and individual dimensions, all of which in one way or another have a bearing upon writing skill formation. Therefore, the objective of the paper was to provide the rationale for a socio-psycholinguistic model for ESP writing skill diagnostic testing, accounting with the variables related to this ability in professional settings.

From the theoretical point of view, the present study offers a new model to approach ESP diagnostic testing of writing skill formation. The model encompasses some of the most important variables with an incidence in the formation of this skill.

The paper is divided into two sections. The first is devoted to a brief analysis of the theory behind the social semiotics, psychology, and didactics of ESP writing and testing. The second section argues the socio-psycholinguistic model.

SOCIO-PSYCHOLINGUISTIC AND DIDACTIC FOUNDATIONS OF ESP WRITING SKILL FORMATION DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The aim of the present section is to argue in brief an analysis of the theory behind writing skill formation from an interdisciplinary point of view. First, an analysis of some sociolinguistic aspects and genre theory are brought to attention together with the essential psychological concepts and their bearing on the issue in question. The second part is devoted to evaluate diagnostic testing from contemporary Cuba didactics and its implications for ESP writing skill formation in professional settings. In both sections, fundamental categories around which all the paper is organized are defined. The methods used are analysis-synthesis, transit from the abstract to the concrete, and dialectic hermeneutics.

THE SOCIO-PSYCHOLINGUISTIC FOUNDATIONS OF ESP WRITING SKILL FORMATION DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) states that in the child's development language plays a central role, for it is through it that the individual becomes a social being. That is, it is through language that cultural patterns are transmitted. This linguist recognizes that language can be studied from two different viewpoints; first, as an inter-organic phenomenon; that is, as an attribute of mankind; and second, as an intra-organic phenomenon; that is, as a potential form of behavior, internalized and reproduced in his contact with other individuals, man's brain capacity to store is and use it creatively. From this perspective, though far in time, linguistics and psychology converge in a point: the role of language in the individual being's socialization.

In other words, SFL view of the role of language for the human being is exactly the same as that of all Vygotskian founded Psychology. It is through the process of the individual's internalization of the historically created culture that all learning takes place. This is a spiral, gradual, contradictory process, which by means of quantitative accumulations brings about a leap forward towards a qualitatively new formation, which negates the old one, but also contains it.

In relation to writing skill formation in professional settings, the above statement of philosophical, psychological, and linguistic origins is of paramount importance. First, professional or academic texts (from now on, referred either as professional or academic genres) are a property of the discourse community which created them—inter-psychic or inter-organic knowledge; second, the genre users of that discourse community have internalized the rules of the genre to a extent that they make use of them for very well-defined communicative purposesintra-psychic or intra-organic-knowledge; third, to become a member of the discourse community implies the gradual internalization of the genre conforming to very often tacit rules expressed in individual text samples. Finally, the whole process of internalizing leading to the skill formation is gradual, which means that it is subjected to time, and personality factors, which raises the contradictory aspect of learning. It is contradictory in the sense that the social form of knowledge does not identify with that of the foreign language learner in terms of discourse patterns, knowledge, and command of the L2. Therefore, ESP writing skill formation is a complex and dialectic process.

The key in writing skill formation is to focus teaching to the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which is the difference between what the learner can do alone and what he can do with the help of others. The ZPD is revealed through diagnostic testing. In other words, diagnostic testing tasks must seek to reveal those mature forms of knowledge in the process of being internalized so as to make them constituent parts of the new formation.

From a SFL viewpoint, this means teaching must be focused on how the field, tenor, and mood of discourse take expression in the genre object of study; that is, how extra-linguistic constraints are expressed in language terms and how language use is consistent with the system of the L2 accepted written forms. Previous work on the area,7-10 corroborate that "the social occasions of which texts are part have a fundamentally effects on texts. The characteristic features and structures of those situations, the purposes of the participants, the goals of the participants all have their effects on the forms [and contents] which are constructed in those situations".4

However, generic features and the foreign language system are hardly the only aspects to learn in professional communication. Other aspects such as writing process and strategies are essential too. True, writing is subjected to the process of transformation of thought into language. But the complexity of the process is not always the same. It depends on the complexity of the thought to be expressed. For instance, it is not the same to write a complaint letter as to write a scientific report, nor it is the same to write a doctoral dissertation as to write its scientific findings in plain language for a popular science magazine.

Teaching genre process writing, therefore, is closely related with choice of writing strategies adequate to the text to be produced. A strategy is defined as a "plan that is intended to achieve a particular purpose".11 In the first of the two examples mentioned above, the complaint letter writer wants to object about something; he only needs to put that in writing which means finding the language to do it according to his state of mood. The scientific report, on the contrary, covers what scientific literature on the topic says, the writer's position about scientific propositions, the problems, object, object, research methods, results, discussion, and conclusions. To put all that in writing demands complex forms of thought: abstraction, comparison, generalization, all of which will be expressed mainly through description and argumentation in a synthetic enough piece of text to meet the requirements of scientific prose, so that it is accepted as such by the intended consumers. Therefore, selection of the correct strategy is paramount to academic genre production.

Hitherto, the aspects mentioned deal with inter-psychic knowledge which has to be internalized. But what should be said about the learner? Isn't he one who is supposed to learn? Doesn't he deserve a word?

In practice, ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing is not conceived for the learner as a distinct, unique personality, but to the product of his work: the academic genre. If the learner is one of the active components in the teaching learning process, if this is learner-centered, and based upon his needs, it follows that there must be some moment during the process in which the affective sphere of personality is assessed.

Personality is the unity of affective and cognitive contents with a stable organization… historically the result of the human being's process of individualization in interaction with society, which regulate behavior. No content of personality can be said to be entirely affective or entirely cognitive, though a given content can be said to be more affective than cognitive and vice versa. For foreign language teaching learning, personality contents with a strong affective component are essential. Among them motivation and need are considered very important.12-13

The unity of cognitive and affective processes operates at different hierarchal levels in personality, from the selection of perceptual processes to personality. At this level, thought is the most complex expression of the unity. Thought functions as instrument of motivation, of its contents as an expression of motive, and of its operations as mobilizing energy. Nevertheless, thought preserves its functional autonomy and actively influences on the motive. It is both a way to express motives and the cognitive source for its development.

All the above has its bearing in ESP writing skill formation. It is known that a strong relation between need and motivation exists. That is, needs are real and thought-mediated and are fulfilled through activity. Motivation is the leading force to fulfill the task and reach the objective. A need is never satisfied if it is not mediated by thought.

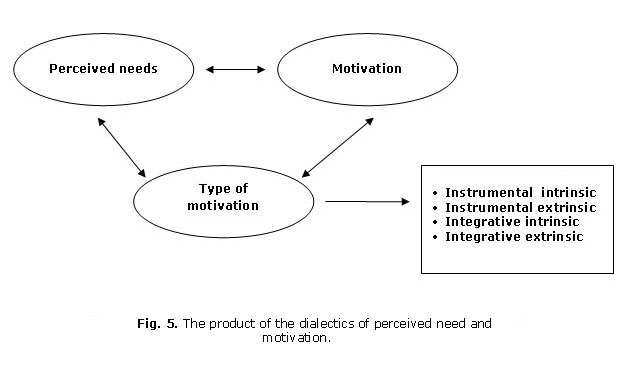

This relationship between need and motivation can be expressed in four different types of motivation; each expresses how thought has appraised the need to learn the object of study (academic genres). As a result there are intrinsic integrative or intrinsic instrumental types of motivation and extrinsic integrative or extrinsic instrumental types of motivation.14-15 Therefore, the above is an important aspect to take into consideration in the teaching learning process of academic genres, because individual personality features are unique and unrepeatable. Similar types of motivation may, and will surely, coincide in the language classroom, but their contents will never be the same. Hitherto, the socio-psycholinguistics aspects analyzed justify the need to consider them as part of diagnostic testing in ESP writing skill formation.

THE DIDACTIC FOUNDATIONS OF ESP WRITING FORMATION DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Academic writing is believed to be cognitively complex. The learning of academic vocabulary and discourse style is particularly difficult. According to cognitive theory, communicating in writing is an active process of skill development and gradual elimination of errors as the learner internalizes the language. Indeed, learning is the product of the complex interaction of the linguistic environment and the learner's internal mechanisms. With practice, there is continual restructuring as learners shift these internal representations in order to achieve increasing degrees of mastery in the L2.

From a didactic viewpoint, the role of diagnostic testing is the constant monitoring of skill formation. Therefore, diagnostic testing is no longer seen as an activity for the beginning and end of the course. It is the continuous didactic device teachers make use of to discover which areas of learning are in the ZDP. At the same time, it cannot be conceived as an additional activity to the teaching learning process, but as an integral part of it.

Cuban contemporary didactics characterize diagnostic testing as systemic, preventive, transforming, corrective, and developmental. 2,6,15,16 In other words, diagnostic testing is described as a pedagogical category far away from error detecting and close to prevention, transformation and development for both the teacher and the student. First, by means of error prevention, the instructor can help to avoid negative feelings in the learning environment; second, by means of the adequate use of the information obtained in testing, the instructor can transform his own teaching and his students' learning; third, by means of feedback, both the teacher and the students will focus in those aspects of formation which impede further development. In this sense, diagnostic testing accomplishes the three functions of the learning process: educational, developmental, and instructional.

Research in learners' lack of progress in writing may be due to the following social reasons:17

- Negative attitudes toward the target language.

- Continued lack of progress in the L2.

- A wide social and psychological distance between them and the target culture, and,

- From the cognitive point of view, this same author synthesizes:

- Lack of competence in the L2 due to poor instruction.

- Incorrect choice and follow up of writing strategies.

- Negative transfer from the L2.

- Poor or no planning and/or revision of drafts.

In a study of pre-graduate and post-graduate medical university students Forteza (2000, 2008) found that other related causes can be:2,6

- Lack of familiarity with the genre and rhetorical structures.

- Discourse progression.

- Poor understanding of the genre communicative purposes.

- Understanding of writing as a task and not as communication.

Putting the socio-psycholinguistic and didactic perspectives together, writing in a second language is a complex process involving the skill to communicate in the L2 (learner output) and the skill to construct a text in order to express one's ideas effectively in writing. Finding out which social, motivational and cognitive factors related to writing skill formation influence on the learning situation will, undoubtedly, help in assessing the underlying reasons why L2 learners exhibit particular writing errors. These factors can be conceived as variables and represented. See diagram in appendix.

These affective/motivational, linguo-procesal, and social variables pose a challenge to the didactics of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing. If all of them influence on ESP writing skill formation, therefore, the study of the text (the written genre) based on static indicators will only show the learner's incompetence to deal with professional communication, and no more. The response to the challenge is a new model for this type of pedagogical activity.

A SOCIO-PSYCHOLINGUISTIC MODEL FOR ESP WRITING SKILL FORMATION DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The present section argues a new model for ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing in which scientifically founded variables account for the student's performance throughout all the learning process until he is able to produce a genre similar to real life samples. Therefore, genre learning is no longer considered as producing a piece of written text, it is thought of as a way of learning how to behave in the new discourse community, a kind of social action (figura 1).

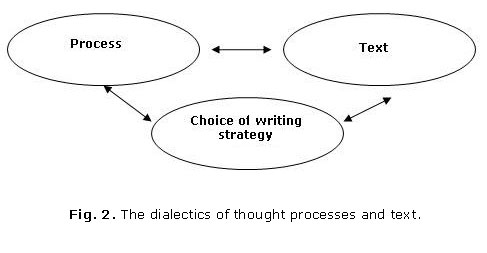

Writing is an activity. Writing is an activity is the sense that it involves actions such as planning, search, organization, and choice of information, drafting, revising, and editing. All these actions are thought mediated. It was argued before that all texts involve these actions; however, their complexity depends on the conditions of writing, or to put it in other words, the kind of text to be produced. Therefore, thought processes and product establish a dialectical relation of cause-effect. The more complex the text, the more thought processes involved, and viceversa. This dialectical relationship can be further developed by a correct choice of a writing strategy (figura 2).

This argument has its foundation on Leontiev and Galperin's skill-related concepts of actions and operations.18-20 A skill consists of actions which once carried out make reaching the objective possible. The operations are condition- dependent; for example, the complexity of the task. These concepts are relative; in the case of a complex skill, such as when writing a research article the writer has to know how to plan; how to organize both strategic actions; and also how to revise, how to edit. In fact, planning, organizing, drafting, and editing are skills in themselves, acting as actions for a complex skill. Whereas anyone can write a shopping list, a simple skill, without much preoccupation for the second, third, and fourth actions. It follows some complex skills (e.g. arguing, narrating, assessing, and writing) comprise actions which in turn can be skills in themselves. Therefore, correct choice of strategies (how to tackle the task conditions) is essential in professional writing.

Writing is also communication because any piece of written language has a communicative purpose. To achieve its communicative purpose, language is always in the form of text, and as text it always belongs to a particular genre. Based on Leontiev's Activity Theory,21 a genre is the mediating instrument in the relationship established between the writer and his reader. Genres are always the property of a particular discourse community, and domain of the genre determines the role of the members. As a result, mastery of the genre language conventions is essential to be accepted as a full member in any discourse community.

Pre-graduate and post-graduate ESP students are usually members of their professional discourse community. They are mostly academic genre consumers. When the need to enter the discourse community in the foreign language arises, the first problem they encounter is not the lack of competence in the L2. Indeed, most ESP students are very usually competent users of the foreign code. The point is that they do not know how to make use of it within their profession. The contradiction is, therefore, a matter of expressing thought/knowledge in another language. This contradiction can be set in motion through information derived from diagnostic testing on the positive and negative transfer of metafunctions from the L1 to and within the L2 (figura 3).

The ideational, interpersonal, and textual metafunctions of all languages are the same. They are expressed in the variables field, tenor and mode of discourse in a particular context of situation or register. Therefore, learning the foreign code for writing academic purposes is a matter of transference from what is already known. It is discovering the shared universals of scientific writing style: discourse development and organization, syntax, morphology, vocabulary choice, preferred communication patterns, mechanics and punctuation. As competent users of their mother tongue and as consumers of genres in their own language, ESP learners know the metafunctions of academic discourse. Therefore, diagnostic testing should aim at what is known in the L1 to favor transfer to the L2, again the ZPD.

An essential viewpoint is that all genres control a set of communicative purposes within certain social situations and that each genre has its own structural quality according to those communicative purposes.22 Therefore, the communicative purposes and the structural features should be identified when genres are used in writing.

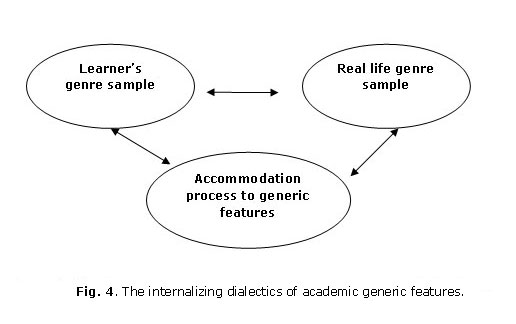

Genre learning is a gradual process of accommodating academic writing to the expectations of the foreign academic discourse community. On one side, the actual samples of texts the learner can produce when the process of learning is taking place are far from similar to real life genres. Diagnostic testing should, therefore, aim at those instances of the genre production which are in the ZDP. That is, which aspects of the genre the learner can produce alone, which with help, and which need further teaching and practice (figura 4).

Generic features are socially/institutionally constrained. In the case of academic genres these limitations are clearly evident. For example, specialized journals regulate the kinds of contents and types of research articles submitted for publication, layout, sections, presentation of additional information and bibliographical references, just to mention some. Though extra-linguistic, these restrictions are expressed through language. Therefore, the learning of generic features is a gradual process of accommodation to social/institutional demands to satisfy the consumer's expectations.

Hitherto, significant categories related to external variables in ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing have been analyzed. These external variables account for aspects of discourse properties of genre in academic settings and adequacy of academic writing style. However, another important variable, an internal one, the individual ESP student as the most important component of the teaching learning process has very often been overlooked or simply mistreated.

The personality factors which have been given prominence in foreign language teaching literature are age, cultural background, attitude, aptitude, interest, perceived needs, and motivation. As mentioned elsewhere before, a strong relation arises from the combination of perceived needs and motivation. This combination brings with it different types of motivation.

The ESP student goes into academic writing for different motives; first, he may want to enter the academic discourse community to make his home-based research known. In this case, his type of motivation is said to be instrumental. Second, he may want to become a member of the discourse community, but within the dwellings of that discourse community; in this case, the type of motivation is said to be integrative. Furthermore, he may do any of those because he himself wants to do so. He has perceived so as a need; that is, intrinsic motivation. On the contrary, he may have been pressed by external agents such as his institution, his economic situation; that is extrinsic motivation. Therefore, there are four different types of motivation (figura 5).

The type of motivation is very commonly related to the student's self-assessment concept. Self assessment in foreign language learning is the result of complex interactions of the student's history in language learning and present experience. Several factors for example, the teacher's and/or peer opinion, and learning outcomes are very strong external influences in self-assessment formation. When self-assessment is positive, the student will perceive language learning as a challenge, and will make all efforts to meet to that challenge. On the contrary, when it is negative, as he already assumes he is going to fail, the channels for learning will be blocked.

For ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing, types of motivation and self-assessment should be seen as interacting configurations. The point is to gather information so as to provide the students with positive experiences in learning how to write in the profession and to discover the motivation type so as to move towards a more favorable form of perceiving the learning experience as meaningful, enhancing self-assessment, thus facilitating appropriation of the skill.

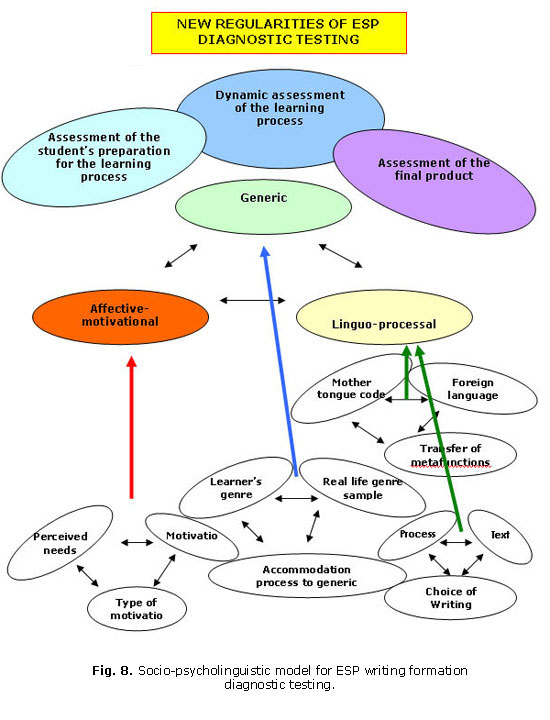

The social and psychological categories dealt with until now represent isolated variables which give rise to configurations of a higher order of integration: the dimensions of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing. These dimensions are the linguo-processal, the generic, and the affective-motivational. They account for different aspects which have to be taken into consideration in ESP writing diagnostic testing.

The linguo-processal dimension arises from the dialectic interaction of thought-processes, text and choice of strategy plus the interactions established between the mother tongue, the foreign code, and the transfer of metafunctions from the L1 and from the already known in the L2. The generic dimension is revealed from the interaction of the real ESP competence in text producing the student presents with, the real competence he is to achieve to produce a real life sample, and the moving category, the necessary accommodation process of the writing output to the obligatory features of the genre. The affective-motivational dimension owes its existence to the interactions produced by types of motivation and self-assessment. These dimensions coexist in ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing (figura 6 ).

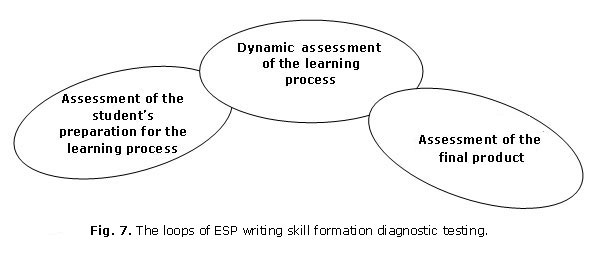

One of the criticisms of today's model for writing diagnostic testing is that it is an activity for the beginning of the course; another is that it only takes into consideration fixed indicators related to the system of the language and the formalities of the written language. The introduction of the above mentioned dimensions adds more indicators accounting for more aspects to be taken into consideration. The aspect to be solved now is how to carry out a continuous diagnostic testing process during ESP writing skill formation. The answer is to carry out the process in interconnected loops.

The loops of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing are closely related to the dimensions of the process. A unifying principle makes that relation possible: Each loop of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing represents the development of the skill at a specific moment of time in a particular variable belonging to a particular dimension.

The Loops of the ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing process are: Assessment of the student's preparation for the learning process, Dynamic assessment of the learning process, and Assessment of the final product. Their relation with the dimensions is as follows:

An adequate assessment of the student's preparation for the learning process entails:

- Finding out about his communicative competence in the L1

- Assessing his previous experiences in foreign language learning

- Learning about his knowledge of the genre object of study and the role he gives in the practice of his profession

An adequate dynamic assessment of the learning process comprises:

- Learning about his mastery of the foreign language system

- Determining his use of effective writing processes

- Getting acquainted of his knowledge about writing strategies , which he uses and prefers

- Assessing the degree of affective commitment with learning the skill

- Determining the degree of approximation to the discursive characteristics of the genre object of study

An adequate assessment of the final product consists of:

- Assessing the degree of affective commitment and change with the new learning

- Determining to what extent the product is similar to real life samples

- Evaluating if the scientific functional style has been used accurately

- Evaluating the extent to which the system of the language and the written language conventions have been used correctly

The conception of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing in loops closely related with the three dimensions stated before makes it possible for new qualities in this type of process to arise. First, ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing becomes professional in the sense that the students learning and products get closer to real life academic demands. For example, if it is an article what he writes, it has to communicate as an article. Second, diagnostic testing is converted into a developmental process for it sets the foundations for other types of learning within the profession. Last, diagnostic testing as conceived in the three loops and three dimensions develops into a personalized process, centered in the individual learner making him responsible with his own learning at the time he is offered all the help he needs for positive change (figura 7 ).

The socio-psycholinguistic model for ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing presented so far envisions the combination of product, process, and genre approaches concepts to academic writing; at the same time, it focuses on the individual learner's needs, motivation, and self-assessment as important variables to this endeavor (figura 8). The adoption of the model results in major changes in different components of the teaching learning process, putting into motion new regularities.

The new regularities in the ESP writing skill formation process brought about by the model enhance its didactic possibilities towards success. First, the objectives of the teaching learning process are conceived in terms of real communication acts rather than in artificial text writing such as sentences, paragraphs, and compositions. Second, the contents of writing include not only the system of the language, but also how these are constrained by social/institutional constrains, writing processes, choice of strategies, how to transfer form one language to another in a real communication task. Third, the approach is basically generic for it is genre writing what the ESP student needs to learn to insert himself in the academic discourse community. Fourth, the teaching aids are updated with real communication samples, authentic texts, which have the role of how to mean in that discourse community, facilitating the understanding of essential concepts such as rhetorical structures, communication patterns, reader's expectations, style, and hedging. Last, diagnostic testing is not evaluation. It is finding out the causes which impede development and learning. Qualitative in nature, diagnostic testing dissociates itself from statistic analysis, centering in personality and performance variables of which numbers can say very little.

ESP writing skill diagnostic testing as presented in the model has different instructional, developmental, and educational effects on the learner. Thus, writing skill formation:

- Increases consciousness level about the linguistic processes in the L1 and of its writing forms in particular.

- Helps in the process of learning the foreign language since writing is another channel in its internalizing process.

- Contributes to the development of thought skills and creativity.

- Increases the capacities to plan, organize, and control verbal activity.

- Allows the assimilation of other culture's writing and their critical assessment with respect to the forms of expression of other men.

- Increases the possibilities of insertion in a new discourse community and an easier access to the workforce market, at the time he defends his identity and culture.

- Makes active participation in academic life possible.

The Socio-Psycholinguistic Model for ESP Writing Skill Formation Diagnostic Testing is a conception founded on sociolinguistic, psychological, and didactic criteria aimed at giving a pedagogic response to structuralist and behaviorist ideas underlying ESP writing diagnostic testing today. It encompasses social, linguistic, language processing and transferring variables together with affective personality factors on dialectic contradiction bases.

Making use of relevant research in discourse linguistics, it introduces the generic dimension for writing skill formation diagnostic testing. The generic dimension of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing fills the gap in reference to the social/institutional constraints expressed through language in academic discourse. At the same time, it reveals new qualities and regularities for this type of pedagogical activity.

The linguo-processal and affective-motivational dimensions of ESP writing skill formation diagnostic testing put together—often neglected or treated in isolation— variables of learning which have a strong bearing in language learning. The information obtained from this type of diagnostic testing will undoubtedly be useful in the teaching of other skills. Finally, the conception of the model in loops allows for constant monitoring of this skill formation and can be used in different educational scenarios.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

- Jordan R. English for academic purposes (EAP). Language Teaching Journal. 1989;44(1):1501.

- Forteza Fernández R. Indicators for writing skill formation diagnostic testing. Master's dissertation in English Language Teaching. Holguín: Instituto Superior Pedagógico; 2000.

- Kern R. Literacy and language teaching. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.; 2000.

- Bhatia VK. Analyzing genre: Language use in professional settings. New York C: Longman. 1983.

- Chi B. Issues in assessing the academic writing of students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds: Preliminary findings from a study on lecturers' beliefs and practices. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne; 2003.

- Forteza Fernández R. Diagnostic testing of the formation and development of writing ability in English for Specific Purposes in Medical Sciences Students. Doctoral Dissertation. Holguín: Universidad de Holguín; 2008.

- Kress G. Genre as social process. In: Cope B, Kalantzis M (eds.) The Powers of Literacy: A genre approach to teaching writing. London: Falmer; 1993.

- Swales J. Genre analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- Forteza Fernández R. Estudio lingüístico comunicativo de los planes de cuidado en enfermería: perspectivas didácticas. Acimed. 2003;11(2). Disponible en: http://bvs.sld.cu/revistas/aci/vol11_2_03/aci070203.htm [Consultado: 7 de octubre de 2009].

- Forteza Fernández R. El reporte de caso en medicina y estomatología: morfofisiología de género. Acimed. 2006;14(1). Disponible en: http://bvs.sld.cu/revistas/aci/vol14_1_06/aci09106.htm [Consultado: 4 de octubre de 2009].

- Oxford University Press. New Oxford advanced learner´s dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- González Serra D. Psicología de la motivación. La Habana: Ecimed; 2008.

- Brown D. Principles of language learning and teaching. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1987.

- Mc Donough S. Psychology in foreign language teaching. La Habana: Edición Revolucionaria; 1989.

- Abreu E. Diagnóstico de las desviaciones del desarrollo psíquico. La Habana: Pueblo y Educación; 1990.

- Ponce S. Concepción teórica-metodológica integrativa para el diagnóstico psicopedagógico de los niños de cero a tres años de edad. Tesis en opción al grado científico de Doctor en Ciencias Pedagógicas. Holguín: Instituto Superior Pedagógico. 2004.

- Myles J. Second language writing and research: The writing process and error analysis in students texts. TESL Journal 2002;6(2 A-1). Disponible en: http://www.kyoto-su.ac.jp/information/tesl-ej/ej22/a1.html [Consultado: 3 de octubre de 2009].

- Talízina N. Psicología de la enseñanza. Moscú: Progreso. 1988.

- Álvarez de Zayas C. La escuela en la vida. La Habana: Pueblo y Educación. 1999.

- Fuentes González H. Teoría holístico configuracional y su aplicación a la didáctica de la educación superior. Santiago de Cuba: Universidad de Oriente; 2002.

- Russel D. (1997). Rethinking genre in school and society: An activity theory analysis. Written Communication. 1997;4(4):504-54.

- 22. Kay H, Dudley-Evans T. Genre: What teachers think [Electronic version]. ELT Journal. 1998;52(4):308-14.

Received: November 11, 2007.

Accepted: December 22, 2007.

Ph.D. Rafael Forteza Fernández. Facultad de Enfermería. Carretera del Valle, Pueblo Nuevo. Holguín. CP: 80500. E-mail: forteza@enfer.hlg.sld.cu

Processing Card

Classification: Original article.

Terms suggested for the indexation

According to DeCS1

EDUCATION, MEDICAL; STUDENTS, MEDICAL.

EDUCACIÓN MÉDICA; ESTUDIANTES DE MEDICINA.

According to DeCI2

TECHNICAL EDUCATION; LEARNING.

ENSEÑANZA TECNICA; APRENDIZAJE.

1BIREME. Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud (DeCS). Sao Paulo: BIREME, 2004. Available from: http://decs.bvs.br/E/homepagee.htm

2Díaz del Campo S. Propuesta de términos para la indización en Ciencias de la Información. Descriptores en Ciencias de la Información (DeCI). Available from: http://cis.sld.cu/E/tesauro.pdf

Copyright: © ECIMED. Open Access contribution, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Shareware License 2.0, which allows the consultation, reproduction, public display and use of the results on practice as well as all of its derivates, without commercial purposes and with an identical license, as long as the author or authors is adequately cited as well as the source.

Cite (Vancouver): Forteza Fernández R, Gunashekar P. A socio-psycholinguistic model for English for Specific Purposes writing skill formation diagnosis. Acimed 2009;19(6). Available from: [Consulted: day/month/year].