Meu SciELO

Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista de Ciencias Médicas de Pinar del Río

versão On-line ISSN 1561-3194

Rev Ciencias Médicas vol.26 no.2 Pinar del Río mar.-abr. 2022 Epub 01-Mar-2022

Original article

Training in a healthcare area to deal with COVID-19

1University of Medical Sciences of Santiago de Cuba. Camilo Torres Restrepo Teaching Polyclinic. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba.

2University of Medical Sciences of Santiago de Cuba. Faculty No. I of Medicine. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba.

Introduction:

Cuba conceived an intersectoral work strategy to contain under the minimum risk, the introduction and dissemination of the new coronavirus; among them, the training of healthcare personnel for diagnosis and care.

Objective:

to describe the results of the training carried out at Camilo Torres Restrepo teaching polyclinic staff to deal with COVID - 19 pandemic.

Methods:

a descriptive, observational and cross-sectional study conducted at Camilo Torres Restrepo teaching polyclinic, Santiago de Cuba in the period between March and September 2020. The target group consisted of 798 people (553 workers and 245 students). The research was developed in three stages: socialization of the problem, organization of the training and implementation of training actions, active survey.

Results:

training was given by 23 professionals. The training of 96,8 % of the personnel to be trained was achieved. The lowest training percentages were achieved among vector personnel (86.3%) and medical interns (93,3 %). Of those trained, 1,8 % did not receive the session on biosafety. Of the healthcare personnel trained, 94,1 % were involved in the active survey. A total of 96,2 % of the population was screened, 74 suspected cases were detected (0,40 %) and only 2 patients were confirmed (0,01 %).

Conclusions:

the training allowed adequate results, with a high number of people trained and incorporated to the active survey, which was evidenced in the high levels of screened population and low numbers of suspects and positives.

Key words: COVID-19; CAPACITATION; PRIMARY HEALTH CARE; INVESTIGATION

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses implicated in a wide variety of diseases affecting humans and animals.1 Until the last century coronaviruses had been associated primarily with non-serious respiratory infections in humans. Since then three new coronaviruses have emerged and spread in multiple countries. At the turn of the century Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) was diagnosed in China and spread to 29 countries, with 8,096 confirmed patients and 774 deaths reported. 2 In September 2012, the first case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) also associated with a coronavirus was reported, and as of July 2019, 2 458 confirmed cases and 848 deaths were reported in 27 countries, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO).1,2

On December 31st, 2019, authorities in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, reported a cluster of 27 cases of acute respiratory syndrome of unknown etiology among people linked to a seafood market, of which 7 were reported as severe.3)

The first cases of infection were linked to a live animal market, but the virus began to spread from person to person.4,5) As the number of sick people increased rapidly, the government of the country and healthcare authorities gave priority to the problem, and on January 9th, 2020, a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was detected by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of this country. Its rapid spread made it a huge challenge for all countries and their healthcare systems, as well as for the international scientific community.6,7

On January 30th, 2020, the Director General of the World Health Organization declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Based on the information provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention of China on the identification of a new coronavirus causing the disease COVID-19,8,9 the WHO by itself issued a set of recommendations to the member states. These have been aimed at minimizing the risk of introduction, dissemination and negative effects of an epidemic on the health status of the population.8

In Cuba, since the first reports of the disease in the world, it was decided to devise an intersectoral work strategy, led by the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) and the Civil Defense System (CD), to control the new coronavirus in the national territory, as well as to minimize the negative effects of an epidemic on the health of the Cuban population and its impact on the economic and social sphere of the country. This strategy contemplated the strengthening of epidemiological surveillance, organization of medical care in all health care units and training of healthcare personnel.10,11

On March 11th, 2020, just when the WHO issued the communiqué declaring COVID-19 a pandemic, the Ministry of Health announced the first cases in the country.10 However, the organization and preparation of healthcare personnel to face this epidemiological situation had been improved. The National Direction of Medical Education of the Republic of Cuba also implemented a series of measures and indications aimed at training professionals, technicians, workers in general and students of the National Health System on the new coronavirus in a staggered manner. Emphasis is placed on specific tasks for epidemiological surveillance and medical care.11

The training of healthcare personnel has played an important role in the actions contemplated in the initial protocol. Experience in dealing with other diseases such as dengue and cholera has shown that medical, paramedical and service personnel play a decisive role in mitigating the effects of epidemiological situations.

Actions have not only been developed at the national level, they have been implemented in primary health care, the first link and basics of medical care in Cuba. At Camilo Torres Restrepo Teaching Polyclinic in Santiago de Cuba, an emergency training plan was developed in order to achieve a better understanding of the phenomenon. This facilitated an adequate attention through the investigation of the population of the area for the timely detection of cases and their isolation. The present research was developed with the objective of describing the results of the training of the healthcare personnel at Camilo Torres Restrepo Teaching Polyclinic in Santiago de Cuba to deal with COVID-19.

METHODS

A descriptive, observational and cross-sectional study was carried out at Camilo Torres Restrepo Teaching Polyclinic in Santiago de Cuba between March and September 2020. The target group comprised 798 people who were working at the time of the research, distributed in 553 workers and 245 students who were in the institution as part of the undergraduate teaching-learning process.

Excluded from the study were those who presented a medical certificate, unpaid leave, service in other units, on international missions and other causes, in addition to 23 professors who served as trainers (clinicians, pediatricians, obstetricians, epidemiologists, dentists, healthcare managers, psychologists, comprehensive medicine practitioners).

The research was carried out in three stages:

The first stage

The Board of Directors of the polyclinic discussed the protocols and regulations in the circumstances of COVID-19 pandemic, and made the Teaching Department responsible for the training. The target group to be trained included: managers, physicians, nurses, technologists, graduates, technicians, service personnel and students.

Second stage

Once the problem to be evaluated was chosen, a documentary review of the bibliography referring to the area under discussion was carried out; in the national and international web portals that are available in Infomed through the VHL (Virtual Health Library), in addition to the documents received by the Ministry of Public Health, the provincial and municipal healthcare directors and their defense councils. A training plan was drawn up and a training schedule was created according to areas of responsibility within the structure of the Polyclinic.

Third Stage

The training actions for healthcare personnel in the area were carried out with the use of supplementary means of support (banners made by the teaching group itself, flip charts, bulletins, and data show presentations, among others).

The topics taught in the training focused on the knowledge of the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, its epidemiology, transmissibility, immune response of the organism, clinical manifestations, complications, biosecurity measures, active epidemiological surveillance of Acute Respiratory Infections, carrying out the investigation, control of outbreaks, and the guidelines issued by MINSAP and the defense council at the different levels, to face the Pandemic.

The information was obtained from the documentation of the population survey in the department of Statistics of the polyclinic. The variables studied were: personnel providing training, personnel receiving training, total population, screened, suspected, confirmed and trained in biosecurity.

RESULTS

The teaching staff that provided the training consisted of 23 professionals, 34,3 % were specialists in General Comprehensive Medicine (MGI) (Table 1)

Table 1 Healthcare personnel who provided training according to scientific rank at Camilo Torres Restrepo teaching polyclinic in Santiago de Cuba province during March-September 2020

| Medical Specialties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 2 | 8,69 |

| Pediatrics | 2 | 8,69 |

| Obstetrics | 2 | 8,69 |

| Comprehensive Medicine | 8 | 34,8 |

| Healthcare management | 2 | 8,69 |

| Dentistry | 3 | 13,04 |

| Epidemiology | 1 | 4,34 |

| Psychology | 3 | 13,04 |

| Total | 23 | 100 |

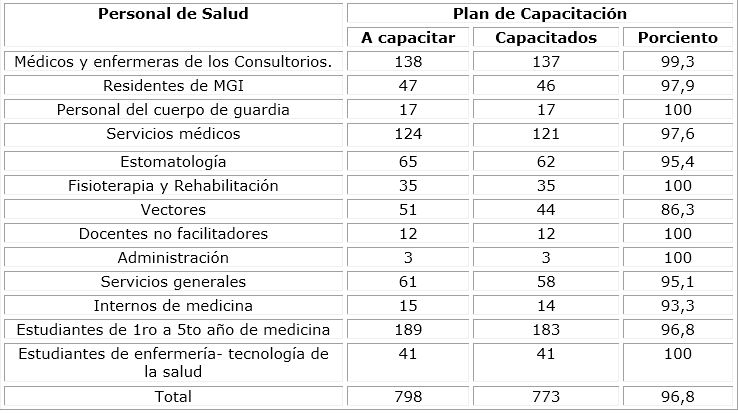

Training was achieved for 96,8 % of the personnel to be trained. The lowest percentages of training were achieved in vector personnel (86,3 %) and medical interns (93,3 %) (Table 2)

Of those trained, 1,8 % did not receive the session on biosafety. Higher levels of training were observed among managers, physicians in assistance, nurses and students (100 %) (Table 3)

Table 3 Healthcare personnel trained on Biosafety

| Trained healthcare personnel | Target group | Trained in Biosafety | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Executives | 14 | 14 | 100 |

| Physicians | 208 | 208 | 100 |

| Nurses | 66 | 66 | 100 |

| Dentists | 62 | 57 | 91,9 |

| Bachelor’s degree professionals | 144 | 139 | 96,5 |

| Technicians | 31 | 28 | 90,3 |

| Students | 238 | 238 | 100 |

| Others | 10 | 9 | 90 |

| Total | 773 | 759 | 98,2 |

The healthcare personnel (94,1 %) who were trained joined the active survey, with higher levels of participation among students and interns (100 %).

Table 4 Healthcare personnel according to those trained and carrying out the active survey

| Carrying out the active survey | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare professionals | 430 | 392 | 91,16 |

| Students and Interns | 238 | 238 | 100 |

| General service personnel | 61 | 54 | 88,5 |

| Others | 44 | 44 | 100 |

| Total | 773 | 728 | 94,1 |

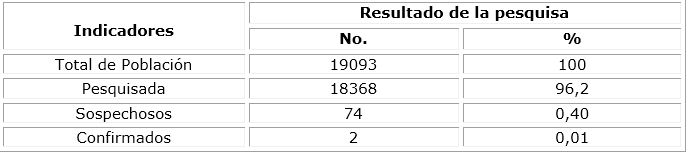

A total of 96,2 % of the population was screened, 74 suspected cases were detected (0,40 %) and only 2 patients were confirmed (0,01 %).

DISCUSSION

According to Chiavenato,12 in his book Introduction to the General Theory of Administration, training is a technique provided to the person or to the individual, where he/she can develop his/her knowledge and skills in a more effective way.

In health services, training is a very important tool if it is desired not only to develop a skill, but also to change the practices themselves, and he points out that continuing education in these services should become a dynamic tool for institutional transformation, facilitating the understanding, assessment and appropriation of the care model promoted by the new programs, prioritizing the search for integrated contextualized alternatives for the care of the population.13

In Chile, the training of health personnel is legalized in article 40, first paragraph of health decree 1889. They provided training to a small group of workers and officials.14 In the Dominican Republic, more than 600 workers were trained on Covid-19, a country that has been hard hit by the pandemic. The main learning tools of these sessions were the guidelines, documents and protocols published in response to COVID-19, focused on national needs and priorities.15

These elements are not different from the training that is carried out in health care institutions in Cuba, as an element of permanent education which, due to the contingency, is done on an emergent basis, but which is part of the existing protocol in the country, supported by the Teaching and Research area of MINSAP (Ministry of Public Health).

There is agreement with the research of some authors such as Figueroa,16 who states that, to face this disease, training should be continuous, reinforced, repeated and planned,16 arguing that healthcare personnel should always be prepared in advance, and Espinosa,17 who advocates the development of rapid and simultaneous training from the onset of the disease, as well as keeping it updated.

Nuñez Herrera and colls,1) in the research carried out in Cienfuegos province in 2020 on the results of the COVID-19 training, emphasizes that the activities carried out with an excellent level of organization, quality, rigor and effectiveness, allow a high number of healthcare professionals to be more prepared to face this epidemiological situation.

Therefore, it is proposed that training on COVID-19 plays a decisive role in the preparation not only of healthcare personnel but also of the population in general, who, through mass organizations in the community, are prepared to face this terrible disease that has a high morbidity and mortality rate.

In turn, clinical-epidemiological screening is a tool used in the control of infectious disease outbreaks or epidemic situations, with the intention of detecting early the emergence of cases or contacts of sick people who may be infected in order to take actions of isolation and study of these people for early diagnosis and timely treatment, and most importantly to reduce the time that these individuals may come into contact with other susceptible individuals, and may infect the latter.17

The circumstances surrounding the onset and development of COVID-19 allowed MINSAP to design the Plan for the prevention and control of the new coronavirus (COVID-19), with the implementation of an active screening program throughout the country, supported by the experiences of previous campaigns against communicable diseases, new strategies adjusted to the current circumstances were adopted.18)

Indications have been issued by the Ministry of Public Health on the methodology to carry out the active survey, one of which is Regulation-07, especially to be applied at the Primary Health Care level, and which was strictly complied with in the healthcare area, this ensured that during this period there were no sick workers or students during the active survey, that there were no cases of children or pregnant women affected and that, of the 74 suspected cases, there were only two (2) cases positive for COVID-19, representing 0,01 % of the total population of the area.

No elements addressing this behavior were found in the literature reviewed. It is inferred due to the novelty of the epidemiological situation mentioned. Active survey for COVID-19 in Cuba has three pillars for its development: the structure of the primary health care level (universal coverage with family doctor-nurse), the allocation program (all citizens are classified in a group in relation to their health status) and the solid support to health by the political and social organizations of the territories.19

It is assumed that Navarro Machado and colls,20 stated that active survey for COVID is a very necessary tool, especially because of its feasibility and cost in our environment; but it will be useful if after the detection of Acute Respiratory Infection, a sufficiently sensitive virological study is performed to allow a diagnostic approach and then an adequate focus control that facilitates the detection of all contacts.

It is concluded that the training allowed adequate results, with a high number of people trained and incorporated to the active surveys, which was evidenced by the high levels of screened population and low numbers of suspects and positives.

REFERENCES

1. Núñez Herrera AC, Fernández Urquiza M, González Puerto Y, Gaimetea Castillo CR, Rojas Rodríguez Y, López Otero TE. Resultados de la capacitación sobre la COVID-19. Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Cienfuegos, 2020. Medisur [Internet]. 2020 [citado 10/09/2020]; 18(3):[aprox. 11 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1727-897X2020000300396 1. [ Links ]

2. Hui DSC, Zumla A. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Historical, Epidemiologic, and Clinical Features. InfectDisClin N Am [Internet]. 2019 [citado 18/04/2020];33: [aprox. 9 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: Disponible en: Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2019.07.001 2. [ Links ]

3. Ministerio de Salud Pública. Plan para la prevención y control del nuevo coronavirus (2019 - nCoV) “Neumonía de Wuhan”. La Habana: MINSAP; 2020 [ Links ]

4. Biblioteca Médica Nacional. Enfermedad por coronavirus covid-19). Atención primaria. Salud del Barrio. [Internet]. 2020 [citado 10/01/2021]; (Especial):[aprox. 9 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://files.sld.cu/bmn/files/2020/04/salud-del-barrio-especial-abril-2020.pdf 4. [ Links ]

5. Ministerio de Salud Pública. Protocolo de Actuación Nacional para la COVID-19, Versión 1.4. La Habana: Ministerio de salud Pública; 2020 [ Links ]

6. Alfonso Sánchez IR, Alonso Galván P, Fernández Valdés MM, Alfonso Manzanet JE, Zacca González G, Izquierdo Pamias T, et al. Aportes del Centro Nacional de Información de Ciencias Médicas frente a la COVID-19. Rev. cuba. inf. cienc. Salud [Internet]. 2020 [citado 21/12/2020];31(3):[aprox. 12 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2307-21132020000300010 6. [ Links ]

7. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Organización Mundial de la Salud. Actualización epidemiológica: Nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19). [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: OPS/OMS; 2021 [citado 29/04/2020]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/file/88667/download?token=bFaWY4XT 7. [ Links ]

8. OMS Recomendaciones básicas de la OMS para protegerse frente al coronavirus. Geriatricarea. [Internet]. 2020 [citado 29/04/2021]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.geriatricarea.com/2020/03/03/recomendaciones-de-la-oms-para-protegerse-frente-al-coronavirus/#login-register 8. [ Links ]

9. Sánchez Duque JA, Arce Villalobos LR, Rodríguez Morales AJ. Enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) en América Latina: papel de la atención primaria en la preparación y respuesta. Atención Primaria [Internet]. 2020 [citado 14/01/2021] 52(6):[aprox. 12p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7164864/ 9. [ Links ]

10. Duardo Guevara Y. Capacitación, esencial en batalla contra el nuevo coronavirus. [Internet]. La Habana: Radio reloj; 2020. [citado 29/04/2020]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.radioreloj.cu/es/salud/la-capacitacion-esencial-en-batalla-contra-el-nuevo-coronavirus/ 10. [ Links ]

11. Beldarraín-Chaple E, Alfonso-Sánchez I, Morales-Suárez I, Durán-García F. Primer acercamiento histórico-epidemiológico a la COVID-19 en Cuba. Anales de la Academia de Ciencias de Cuba [Internet]. 2020 [citado 12/12/2020];10(2):[aprox. 10 p.].Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.revistaccuba.cu/index.php/revacc/article/view/862 11. [ Links ]

12. Chiavenato I. introducción a la teoría general de la administración. 7ma ed. México: Editorial MC-Graw-Hill-Interamerica; 2007. [ Links ]

13. Castillo Estigarribia A, Ferrer Lagunas L, Masalán Apip P. Capacitación del personal de salud, evidencia para lograr el ideal. Horizontes de Enfermería [Internet]. 2015 [citado 12/12/2020]; 26(1): [aprox. 5 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.7764/Horiz_%20Enferm.26.1.29 13. [ Links ]

14. Davini MC, Nervi L, Roschke MA. Capacitación del personal de los servicios de salud proyectos relacionados con los procesos de reformas sectorial. [Internet]. Quito: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2002 [citado 02/01/2021]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-762320 14. [ Links ]

15. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Más de 600 personas son capacitadas sobre COVID-19 y temas de Salud. [Internet]. Santo Domingo: OMS; 2020 [citado 02/01/2021]. Disponible en: Disponible en: www.paho.org/dor 15. [ Links ]

16. Figueroa L, Blanco P. Infección por coronavirus COVID-19 y los trabajadores de la salud: ¿quién es quién en esta batalla? Rev Hosp Emilio Ferreyra [Internet]. 2020. [citado 02/08/2020];1(1):[aprox. 3 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://revista.deiferreyra.com/art_html/Figueroa 16. [ Links ]

17. Espinosa Brito A. Reflexiones a propósito de la pandemia de COVID-19 (I): del 18 de marzo al 02/04/2020. Anales Academia de Ciencias de Cuba [Internet]. 2020[citado 02/08/2020];10(2):[aprox. 40 p]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.revistaccuba.sld.cu/index.php/revacc/article/view/765/797 17. [ Links ]

18. Montano Luna JA, Tamarit Díaz T, Rodríguez Hernández O, Zelada Pérez MM, Rodríguez Zelada DC. La pesquisa activa. Primer eslabón del enfrentamiento a la COVID-19 en el Policlínico Docente “Antonio Maceo”. Revhabanciencméd [Internet]. 2020 [citado 14/01/2021];19(1): [aprox. 11 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1729-519X2020000400010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en 18. [ Links ]

19. Fernández JA, Díaz J. Algunas consideraciones teóricas sobre la pesquisa activa. RevCubanaMed Gen Integr [Internet]. 2009 [citado 21/01/2021];25(4): [aprox. 9p]. Disponible en: Disponible en: Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-21252009000400011&lng=es 19. [ Links ]

20. Navarro Machado VR, Moracén Rubio B, Santana Rodríguez D, Rodríguez González O, Oliva Santana M, Blanco González G. Pesquisa activa comunitaria ante la COVID-19. Experiencias en el municipio de Cumanayagua, 2020. Medisur [Internet]. 2020 [citado 14/04/2021]; 18(3): [aprox. 11 p.]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1727-897X2020000300388 20. [ Links ]

Financing

Received: August 28, 2021; Accepted: February 19, 2022

texto em

texto em