Introduction

Impulsive Buying refers to the phenomenon of making spontaneous, often unnecessary purchases without prior planning. It is usually characterized by its unplanned or last-minute nature (Rodrigues et al., 2021). Impulsive Buying has been identified as a significant contributor to overconsumption and elevated debt levels (Achtziger et al., 2015).

There are many possible explanations as to why people engage in impulsive buying. This study aimed to determine the factors related to impulsive buying, explicitly identifying the role of peoples' attitudes towards money and debt, irrational happiness, materialistic values, and sustainable consumption behaviors.

Irrational happiness is a set of dysfunctional beliefs in which someone sets unrealistic standards regarding the frequency and intensity of personal happiness. For example, people with such beliefs may unrealistically expect to always live in a high-happiness state. Not achieving this may result in frustration and disappointment. Irrational happiness also leads to a sense of entitlement. People who believe they deserve to have the best of everything are often disappointed when they do not get what they want. Irrational happiness may also lead to an egocentric and hedonic approach to life. Overall, irrational happiness is inversely related to satisfaction with life, positive affect, psychological wellbeing, and stress; while being positively associated with negative affect and self-reported stress (Yıldırım & Maltby, 2021). Hedonic values, such as those inherent to irrational happiness, are related to compulsive buying (Tarka et al., 2022).

On the other hand, materialistic values imply a preoccupation with or an excessive desire for material possessions. Materialism is the belief that possessions, wealth, and social status are the key to happiness and success. People with high materialistic values are likelier to engage in higher consumerism, debt, and ecologically damaging behaviors (Kasser, 2016). Therefore, the individual is not the only one affected by materialism; society also suffers. A materialistic culture places a high value on consumerism, leading to increased resource consumption and waste generation.

On this line, people's attitudes toward debt are another essential factor to consider when discussing impulsive buying behavior. It is important to note that debt is not always detrimental, as it can be helpful when used responsibly. However, when debt is used to finance impulsive buying behavior, it can quickly become a problem. Individuals with low levels of self-control usually report higher debt (Achtziger et al., 2015). Additionally, debt may affect an individual financial capacity to pay housing and medical expenses (Sweet, 2020).

On the other hand, attitudes towards money refer to the degree of control and care an individual places over personal finances. For instance, a highly caring individual would rely on different management techniques to supervise his or her income-expenses balance. A high degree of control and supervision over personal expenses relates to low debt levels (de Almeida et al., 2021). Therefore, attitudes towards money and debt are thought to play a role in impulsive buying because they can influence an individual's perceived need for and willingness to purchase a good or service.

It is widely accepted that sustainable consumption behaviors - those that protect and conserve resources for present and future generations- are critical to achieving long-term sustainability (Matuštík & Kočí, 2019). Sustainable consumption behaviors may include, for example: limiting water and energy consumption at home, avoiding food or beverage wastage, avoiding overconsumption of goods and services, buying products with biodegradable components or packing, reutilizing certain goods, recycling clothes, glass, paper, reusing bags, repairing belongings (instead of immediately replacing them), among other behaviors (Quoquab et al., 2019).

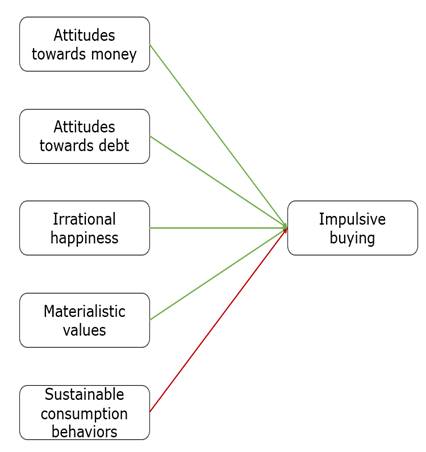

Considering the literature review presented above, the current study aims to test the following hypotheses (see Figure 1):

Hypothesis 1: Attitudes towards money are positively related to impulsive buying.

Hypothesis 2: Attitudes towards debt are positively related to impulsive buying scores.

Hypothesis 3: Irrational happiness is positively related to impulsive buying scores.

Hypothesis 4: Materialistic values are positively related to impulsive buying scores.

Hypothesis 5: Sustainable consumption behaviors are negatively related to impulsive buying scores.

Source: the authors

Source: the authorsFig. 1 - Hypothetical model for the variables related to impulsive buying. Positive relationships are presented in green lines; negative associations are presented in red.

It is essential to study impulsive buying in low-and-middle-income countries for several reasons. First, impulsive buying can significantly impact the economy of a low-and-middle-income country. If a large percentage of the population engages in impulsive buying, this can lead to a decrease in the population's purchasing power and savings level and an increase in debt levels. This can have a negative impact on the long-term economic stability of a country. Finally, impulsive buying can also harm the environment, as people may impulsively purchase products they do not need, which can lead to waste and environmental pollution.

Materials and methods

Instruments

Buying Impulsiveness Scale

The Buying Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) consists of nine items with a five-point Likert scale format (1=Totally disagree, 5=Totally agree) (Rook & Fisher, 1995). Summative scores range from 9 (low buying impulsiveness) to 45 (high buying impulsiveness). The BIS achieved adequate internal consistency in the current study, measured by Cronbach's Alpha, α=0.82, 95% CI [0.79, 0.85]. Example items from the BIS, among others, include:

Attitudes Towards Money

Two items from de Almeida et al. (2021) measured Attitudes toward Money. Participants were asked to rate their degree of agreement with the items:

The ratings were recorded in a Likert scale five-point format (1=Totally disagree, 5=Totally agree). Summative scores range from 2 (high financial control) to 10 (low financial control). Based on data from the current study, the items achieved adequate reliability, α=0.80, 95% CI [0.74, 0.84].

Attitudes Towards Debt

The Scale of Attitudes toward Indebtedness consists of 11 items in a five-point Likert scale format (Denegri Coria et al., 2012). Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Totally disagree) to 5 (Totally agree), with total summative scores ranging from 11 (unfavorable attitude towards debt) to 55 (favorable attitude towards debt). The reliability achieved in the current study was acceptable, α=0.69, 95% CI [0.62, 0.74]. Some items included in the scale are, among others:

Material values

The Material Values Scale- Sort-Form (Richins, 2004), was included in the study. It consists of 15 items with a five-point Likert response set (1=Totally disagree, 5=Totally agree). Summative scores range from 15 (low material values) to 75 (high material values). In the current study, The Material Values Scale-Short Form, achieved an adequate reliability α=0.78, 95% CI [0.74, 0.82]. Some items include:

"I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes"

"My life would be better if I owned certain things I do not have"

Irrational happiness

The Irrational Happiness Scale is a three-item questionnaire with a five-point Likert-type response set (1=Totally disagree, 5=Totally agree). The overall summative values range from 3 (low irrational happiness) to 15 (high irrational happiness). The scale achieved adequate reliability in the current study, α=0.87, 95% CI [0.84, 0.90]. The items in the scale include (Yıldırım & Maltby, 2021):

"I should always be happy in all aspects of my life"

"I must always be happy in all aspects of my life"

"I ought always to be happy in all aspects of my life"

Sustainable consumption behavior

The Sustainable Consumption Behavior Scale consists of 24 items (Quoquab et al., 2019). A five-point Likert-type response set was used (1=Totally disagree, 5=Totally agree), with summative values ranging from 24 (low disposition towards sustainable consumption behaviors) to 120 (high disposition). This scale achieved a high internal consistency coefficient, α=0.91, 95% CI [0.90, 0.93]. Some items include:

"I avoid overuse/consumption of goods and services (e.g., take print only when needed)",

"I use eco-friendly products and services"

Participants

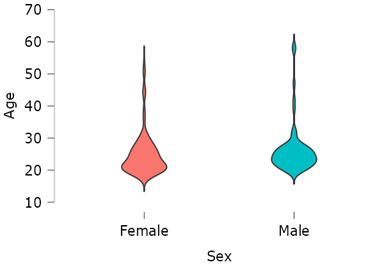

A total of 242 participants completed the online survey. The average age of the respondents was 25.19 years (SD=6.90; Min=18; Max=58). The majority were female (n=175; 72.31%), as men accounted for 27.69% of the sample (n=67). Figure 2 offers a visual description of participants' age and sex. The participants were recruited through non-probabilistic sampling. The online survey was shared through academic mail, social media, and instant messaging services. To participate in the study, the subjects had to:

Ethical considerations

All respondents were presented with an informed consent which presented the purpose of the study, information regarding the data collection and analysis process, contact information for the researcher, a voluntary participation and retirement agreement, etc. No personal information was collected (names, identifications, mails), guaranteeing the respondents' anonymity. The study followed all ethical considerations stated in The Declaration of Helsinki.

DATA ANALYSES

First, the dataset was built using Google Sheets. Where applicable, items with negative orientation were inversely recoded; summative scores were obtained for each scale. The Google Form required participants to answer all questions; therefore, the dataset contained no missing data.

Later, descriptive and inferential statistics were used to study the data and test the hypotheses. Internal consistency scores were determined through Cronbach's alpha, 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Then, the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each scale. Bivariate relationships between variables were assessed through Pearson's r coefficient.

A multiple linear regression model was used to determine the variables that explain Impulsive Buying scores. Finally, an independent sample t-test was used to compare scores between male and female participants; effect sizes, as measured by Cohen's d, were also obtained. Partial regression plots and rainclouds were used to help visualize data. The significance threshold for all hypothesis testing was set at p<.05. All analyzes were done using JASP. The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Results indicate that Impulsive Buying (M=23.26) is significantly and positively correlated with Attitudes toward Money (M=5.48) and Debt (M=41.63), Irrational Happiness (M=12.47), and Materialistic Values (M=41.29). On the other hand, Sustainable Consumption Behaviors (M=94.90) correlates negatively with Impulsive Buying, see Table 1.

Table 1 - Correlation coefficients between the study variables

| Variable |

|

Attitudes- money |

Impulsive buying |

Attitudes-debt |

Irrational happiness |

Sustainable consumption behavior |

| 1. Attitudes-money | 5.48 (2.37) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Impulsive buying | 23.26 (7.55) | 0.62*** (<.001) | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Attitudes-debt | 41.63 (5.94) | 0.09 (0.18) | 0.20*** (<.001) | - | - | - |

| 4. Irrational happiness | 12.47 (3.07) | 0.04 (0.50) | 0.17*** (<.001) | 0.30*** (<.001) | - | - |

| 5. Sustainable consumption behavior | 94.90 (14.57) | -0.01 (0.83) | -0.13* (0.04) | 0.26*** (<.001) | 0.18*** (<.001) | - |

| 6. Material values | 41.29 (8.84) | 0.16 * (0.01) | 0.32*** (<.001) | 0.10 (0.13) | -0.04 (0.54) | -0.13* (0.04) |

|

* | ||||||

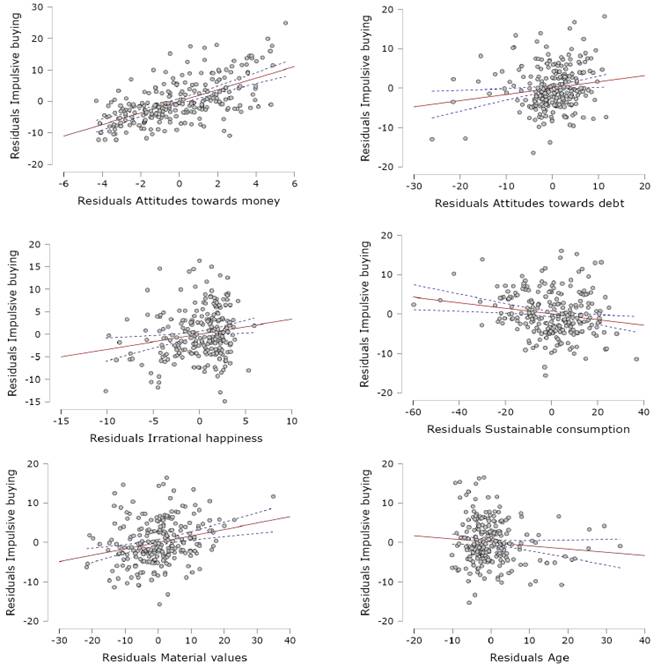

The model explaining Impulsive Buying scores achieved an r 2 of 0.50, equivalent to a large effect size (f 2 =1.01); F (7,234) = 32.84, p<.001, power< 0.99. Individual significant positive predictors include Attitudes Towards Money (β=1.83, p<.001), Attitudes Towards Debt (β=0.16, p<.01), Irrational Happiness (β=0.33, p<.001), and Materialistic Values (β=0.16, p<.001). On the other hand, Sustainable Consumption behaviors have significant negative effects over Impulsive Buying (β=-0.07, p<.001), see Table 2 and Figure 3.

Table 2 - Regression model explaining Impulsive Buying scores

| Model | Predictor | Unstandardized | SE | Standardized | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₀ | (Intercept) | 23.26 | 0.49 | - | 47.96 | < .001 |

| H₁ | (Intercept) | 4.65 | 3.78 | - | 1.23 | 0.22 |

| Attitudes-Money | 1.83 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 11.99 | < .001 | |

| Attitudes-Debt | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 2.47 | < 0.01 | |

| Irrational Happiness | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 2.75 | < .001 | |

| Sustainable Consumption | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.14 | -2.76 | < .001 | |

| Materialistic Values | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 3.95 | < .001 | |

| Sex (Male)ᵃ | -0.37 | 0.79 | -0.47 | 0.64 | ||

| Age | -0.08 | 0.05 | -0.07 | -1.51 | 0.13 | |

|

Source: the authors | ||||||

Source: the authors

Source: the authorsFig. 3 - Partial regression plots between Impulsive Buying and associated scale variables. Confidence intervals (95%) are presented in blue-pointed lines.

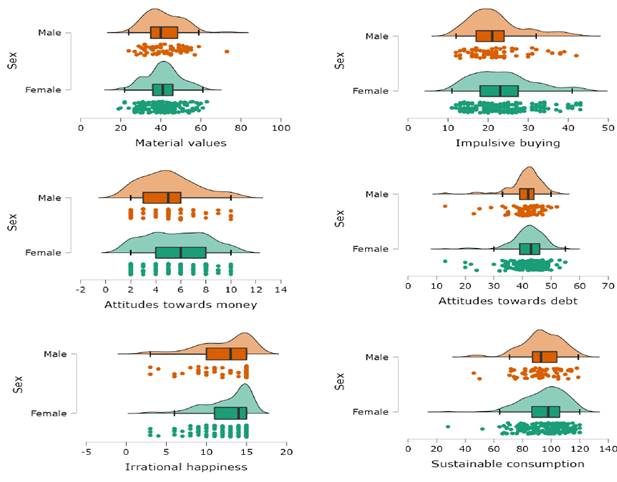

Neither respondents' sex (β=-0.37, p=0.64), nor age (β=-0.08, p=0.13) resulted in significant coefficients. In this sense, a t-test comparing male and female scores further corroborates that neither Impulsive Buying nor any other scale varies significantly and had a small effect size (d). See Table 3 and Figure 4.

Table 3 Variable comparisons by sex

| Variable | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material values | Female | 41.20 | 8.72 | -0.24 | 0.81 | -0.03 |

| Male | 41.51 | 9.21 | ||||

| Impulsive buying | Female | 23.71 | 7.72 | 1.52 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Male | 22.07 | 6.98 | ||||

| Attitudes towards money | Female | 5.63 | 2.41 | 1.70 | 0.09 | 0.24 |

| Male | 5.06 | 2.21 | ||||

| Attitudes towards debt | Female | 41.89 | 5.82 | 1.10 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| Male | 40.96 | 6.24 | ||||

| Irrational happiness | Female | 12.61 | 2.90 | 1.14 | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| Male | 12.10 | 3.47 | ||||

| Sustainable consumption | Female | 95.49 | 14.67 | 1.01 | 0.31 | 0.15 |

| Male | 93.37 | 14.31 | ||||

| Source: the authors | ||||||

Discussion

The results presented here suggest that people less controlling of their finances have a higher propensity to engage in impulsive buying. Previous studies have demonstrated that subjects with high risk-seeking behaviors have more favorable attitudes towards indebtedness (Liao & Liu, 2012). At the same time, higher compulsive buying behavior is positively related to loan dependence (Owusu et al., 2021).

Additionally, higher irrational happiness predicts higher impulsive buying, as people may feel like they deserve to have the latest and greatest product, regardless of whether or not they can afford it. This may be related to narcissistic traits, which are considered a predictor of impulsive buying behaviors (Cai et al., 2015). Previous research suggests that impulsive buying positively relates to purchase-please and hedonism (Santini et al., 2019).

Materialistic values were also found to be predictors of impulsive buying. For one, materialistic people tend to place a high value on objects and possessions. They may view certain items as status symbols (Oh, 2021), and feel a need to keep up with the latest trends in order to maintain their social standing. As a result, they may be more likely to make impulsive purchases to keep up with their peers. Additionally, materialistic individuals may be more likely to experience feelings of dissatisfaction and emptiness (Isham et al., 2022). Consequently, they may believe that acquiring new things will make them happier and more fulfilled, leading them to engage in impulsive buying behaviors.

Nonetheless, sustainable consumption behaviors may serve as a protective factor against impulsive buying. In this sense, recent studies have concluded that frugality is significantly affected by the individuals' consciousness of sustainable consumption (Suárez et al., 2020). One of the critical reasons why consciousness of sustainable consumption affects impulsive buying is that it helps people to become more aware of the actual cost of the things they buy. When people are conscious of the environmental and social costs of the products they purchase, they are less likely to make impulsive buying behaviors. Instead, they are more likely to think carefully about their purchases.

These findings have important implications for policy and interventions aimed at reducing impulsive buying behavior. In particular, interventions that seek to address the underlying psychological factors that lead to impulsive buying may be more successful in reducing this behavior than focusing solely on changing consumer behavior. Based on the findings of the present study, it is recommended that interventions aimed at reducing impulsive buying should take into account individual differences in attitudes towards debt and money, irrational happiness, and materialistic values. In addition, sustainable consumption behaviors should be promoted as a protective factor against impulsive buying.

In this line of thought, circular economy practices may be useful in promoting better resource and waste management. In a traditional linear economy, products are often designed for single-use and then disposed of after just a short period of time. This creates waste and forces people to constantly buy new things to replace the old. In a circular economy, however, products are designed to be reused, repaired, or recycled, so that they can have a longer lifespan.

Regardless of the relevance of these findings, the study has limitations to be considered. First, the non-probabilistic sampling approach may restrict the generalizability of the results. Second, despite the multivariate approach utilized, the study did not contemplate other variables with potential explanatory effects, such as income, educational level, etc. Third, the data collection techniques are self-reported; as such, they depend on the introspection capability of the respondents. Fourth, the transversal nature of this study only allows gaining knowledge restricted to a specific time. Therefore, no inference can be made about the evolution of the variables through different historical conditions.

Future studies could benefit from qualitative and mixed-methods approaches to better understand the subjective experiences that promote or discourage impulsive buying behaviors. Further research could also study the role of locus of control, emotional intelligence, objective and subjective income, when considering this type of consumer behavior. Considering the contextual dynamic of Honduras, a low-middle-income country, replications are needed to corroborate the evidence further presented here. Additional studies in such countries could provide valuable insights regarding consumer behavior in the global south.

Conclusions

This study analyzed factors related to Impulsive Buying in the Honduran population. Subjects with higher scores in Attitudes towards Debt and Money, Irrational Happiness, and Materialistic Values, have a higher tendency toward Impulsive Buying. On the other hand, Sustainable Consumption Behaviors are a protective factor, diminishing Impulsive Buying scores. These variables explained 50% of the variance in Impulsive Buying scores. Neither sex nor age is considered a significant predictor. Further studies are needed to understand the dynamics of these variables in low-and-middle-income countries.