Introduction

Think Aloud Protocols (TAPs) are methodological instruments in which the subject verbalizes his/her thoughts, sensations or opinions while carrying out an activity (Batista, et al., 2021; Wolcott & Lobczowski, 2021). In psycholinguistics, these have been used to explore the causes and effects, among others, of linguistic processing in the brain.

Given the fact that, in translation, as a process of mediated bilingual communication (Gregorio, 2018), numerous procedures converge to enable or affect, from the linguistic-cognitive point of view, the proper development of this communicative mediation; the TAP technique becomes a relevant method for the study of the processes that intervene in the translator's mind when performing a translating task. This, in turn, offers important data that contribute to clarify the causes of translation errors and to guide its treatment. Consequently, it is necessary to deepen the theory of TAPs, and the conventions for their use in the cognitive diagnosis of translation errors.

TAPs must be based on a task that provides the content of the verbalization. Consequently, the researcher must take into account several criteria: (a) the subjects must not be able to solve the problem in an automated way, which implies that the verbalization must have a meaning for them, therefore, it must be part of an interaction; (b) the task must be representative with respect to the cognitive process involved; (c) the task must be able to be verbalized, so that it involves taking up contents that are in working memory (Working memory being understood as the cognitive proceeding of the subjects while they perform the task. This proceeding should not be cumulative, but verbalized as it occurs mentally), and should not cause task overload; (d) the task should not proceed too fast to allow synchronization with the verbalized protocols (Charters, 2003; Alshammari, et al., 2015).

These conditions apply to translation, as it is a process in which subjects convey messages from one language to another (Vargas, 2019). Therefore, the task is complex in itself, and does not involve automation. The steps that translation subjects follow to perform it, their criteria on the difficulty of the text, the verbalization on how they process translation errors and resolve them become verbal data that is processed and analyzed.

One of the most recurrent errors in translation is lexical-semantic ambiguity. From the perspective of discourse analysis and textual linguistics, this type of ambiguity has been defined by Klepousniotou (2002) and Klepousniotou et al (2012) and reviewed by Escalona, et al. (2019), who relate it to the erroneous selection and/or translation of words in a given context. In this sense, Stevens (2009), Espí (2011) and Escalona and Castro (2013) identify an interlingua lexical group that, by its nature, often causes lexical-semantic ambiguity in translation: false friends (FF), which are words in two languages that are graphically and phonetically similar, but different in meaning.

The main research in this area refers to the works of Fernández (2005), Aske (2015) and Escalona (2017), who identify false friends as a difficulty in translation, highlight the need to conduct further studies on the treatment of this type of error, and offer glossaries of the most recurrent false friends between several language pairs. However, there is no analysis of what happens in the minds of trainee translators when processing false analogues from the source text to the target text, for which the use of the TAPs technique contributes to provide the necessary data.

The main models on which the application of TAPs is based are the dimensional model, the categorical model and the procedural model (Kintsch & Greeno, 1985). This study assumes the procedural model, in accordance to the nature of the objective stated: to analyze the procedures and steps that translation subjects undertake to resolve the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends in the stages of the translation process; namely, comprehension, decoding, re-expression and textual revision (Venuti, 2004; Espí, 2011).

After data collection, the next step is to code the segments according to the designed model. The protocols can then be compared with the model, which is derived directly from the theory. The elements of the procedural model are, therefore, the variables on which the analysis of the verbalized protocols is based. Thus, predictions can be made from the attributes obtained. The expected result is a detailed explanation of how cognitive theories of mental lexicon and the stages of the translation process are integrated in the minds of translators, when processing the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends.

The foregoing is exemplified in the following section, through a diagnosis consisting of a translation task with translators-to-be from Universidad de Oriente, in three different stages: A first stage, where the current state of the processing of lexical-semantic ambiguity caused by false friends is evaluated, and two subsequent stages after the application of a didactic strategy for the treatment of this translation error, in order to corroborate its effectiveness.

Methodology

The objective of the methodology employed was to evaluate the state of processing of the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends in translation. To this end, the method of triangulation of techniques (translation test and TAPs) was applied with translation subjects, in the context of the English Language Program at Universidad de Oriente, through three diagnoses applied at different stages of the academic year.

Actions:

To design and apply a translation test to students of the English Language Program at Universidad de Oriente, who are translators-to-be

To develop and apply an instrument based on TAPs simultaneously to the translation test

To triangulate the data obtained by the application of the former instruments

To characterize the current state of the processing of the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends in translation

Participants

The translation test and the TAPs were applied to 24 translators-to-be of third and fourth years of the English Language Program at Universidad de Oriente in the academic year 2017-2018, and of the fourth and fifth years in the academic year 2018-2019, in order to grant a longitudinal study with the same sample of participants. This sample represents 66.7% of the population, which had taken Translation and Interpreting courses. The selection of these two academic years responds to the fact that the students were already familiar with the subject of Translation, and other subjects that covered significant contents of the different fields of professional practice. Likewise, during these two years, they were on their work translation training period. This allowed for a longitudinal analysis with these same groups, which enabled to corroborate their evolution after the application of the resulting theoretical-practical proposal.

To start the studies of Translation and Interpreting, it is necessary to have reached an upper intermediate level in the foreign language, which was achieved in the previous three academic years (preparatory, first and second). Therefore, it was not necessary to check the language level of the participants in the diagnosis. It is important to highlight that all 24 translator-to-be involved took English as a first foreign language lessons, 14 of them took German as a second foreign language, and the remaining 10 took French. For this reason, the translation test was designed in these three languages.

Procedure

In the three diagnostic stages, the test consisted of translating short texts (in English, German & French) that deliberately contained false friends German-Spanish (for the third year), French-Spanish (for the fourth year) and English-Spanish (for both years). The texts selected are authentic, extracted from the corpus databases DWS (German) and Skell Sketch Engine (French) and Cambridge Corpus of English (English). The false friends were selected based on a frequency of use of more than 1000 co-occurrences, in order to guarantee representativeness in the textual sample.

The three language pairs selected correspond to the languages in which translators are trained at Universidad de Oriente (English as a second language and German or French as a third). Regarding the false friend status, they shared more than 50% similarity in their form; that is, a high degree of resemblance, without additions, omissions, or creation of pseudo cognates. Despite the short length of the texts, the participants were allowed to use dictionaries, since the translation tasks must be developed using all possible means of lexical-semantic decoding to complete them.

Before conducting the test, the translation trainees were grouped in three teams, which did not work simultaneously, but consecutively. The number of members in each team was not standard, but depended on the language pairs in which they had translation experience; hence, of the 24 who translated from English into Spanish, 10 translated also from French into Spanish and 14 from German into Spanish.

Translation subjects were grouped in teams since they had to verbalize about the development of the translation task as they performed it, which individually was not natural, since it could condition both the attitude of the subject and the information obtained in the protocols, which is recognized in the TAPs theory (Charters, 2003). Although group verbalization, unlike the individual one, can condition the non-parallelism between thought and verbalization, it is not the intention of the study to control this aspect: even if not all thoughts are verbalized, the group task provides sufficient data on the cognitive procedure of translation subjects on the achievement (or not) of translation as a process, and the stages for processing the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends. Consequently, the objective is not affected, since the TAPs are also only one of the triangulated instruments. Therefore, teamwork grants the collaborative resolution of the task and a spontaneous verbalization that was more faithful to translation reality.

Verbalizations were recorded as subjects translated. Three groups of verbalized protocols were obtained: one group per language pair involved in the translation. In order to avoid creating biased protocols, the translation subjects were not informed that the intention of the test was to corroborate whether they detected and solved the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends. Therefore, they were informed that the verbalization was intended to analyze what they do to solve a translation task and how.

The study was based on three main codes that respond to the three cognitive steps for the processing of lexical-semantic ambiguity, provided by Cottrell (1994): access, decoding and contextual integration, and the stages of the translation process: comprehension, decoding, re- expression and textual revision (Venuti, 2004; Espí, 2011). The levels of textual sequencing proposed by Elena (2011) were also considered. The integrated vision of these referents is a coherent procedural logic that must be present in the translation practice.

Protocols analysis was conducted by means of a previously designed model, based on these codes. Thus, the procedural model by Kintsch & Greeno (1985) was adopted, since it is consequent with the nature of the diagnosis: to analyze the procedure and steps followed by translation trainees when processing and solving lexical-semantic ambiguity caused by false friends in all the stages of the translation process. The variables for the analysis of the verbalized protocols coincide with the steps proposed in the model. Protocols were segmented and analyzed based on the model, with the purpose of studying how translation subjects develop the translation steps, and how they process lexical-semantic ambiguity within them.

This procedure was performed in a longitudinal study based on achievement patterns devised for two translation performance levels: translation with semantic disambiguation at a basic level (hereafter the Spanish acronyms TB,), and translation with semantic disambiguation at an independent level (hereafter the Spanish acronyms TI).

Initial diagnosis

It was conducted to determine what happened in the minds of the translators when processing the FF present in the source text, what mental procedures they use to re-express them into the target language, how they re-express them in the target text and why. The frequency analysis was used as a statistical technique for the processing of the test, since it complies with all the characteristics of the descriptive scale and the study conditions. This test, together with the TAPs and the observation of the process, allowed the analysis of the medium-term effects as the didactic strategy was applied.

It is worth noting that the application of the statistical technique had an explanatory nature, because it addressed the causes that determined the improvement in the performance of the translators-to-be, from the treatment to the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends. It is therefore evaluated from the total frequency of repetition of the achievement patterns for the two declared indicators. This is confirmed by an integrated evaluation, based on the incorrect or correct translation of the false friends and on the verbalizations that indicated the way in which the translators conducted the process (basic or independent), how many times they performed translations with lexical-semantic disambiguation of false friends at a basic level and how many times at an independent level, in each case.

First diagnosis

A first diagnosis was made after applying the strategy (first semester of the 2018-2019 academic year), which also consisted of a translation test and TAPs. The evaluation of the test is carried out based on the proposed achievement patterns, which implies that the analysis is conducted based on the number of translations with the TB and TI achievement pattern, out of the 48 translations obtained.

Second diagnosis

The second diagnosis, after a longer period following the application of the strategy (second semester of the 2018-2019 academic year), was carried out to corroborate changes in the performance level of the translators trainees in regards to the translations with lexical-semantic disambiguation caused by FF at an independent level.

Discussion

The translated texts were reviewed individually. More translated texts were obtained than the number of participants, since each one made two translation tasks, for a total of 48 texts. The frequency of wrong and correct translation for each of the FF was statistically analyzed in relation to the number of participants who performed the translation.

Initial diagnosis

Test results revealed an erroneous equivalence frequency of 67% for English-Spanish false friends, 82% for German-Spanish false friends, and 76% for French-Spanish. The translation test and the TAPs were analyzed in an integrated way, since the behavior of the variables exposed in the latter contribute to substantiate the results of the former. This integrated assessment is detailed below.

English-Spanish translation

The texts contained 12 false friends, of which seven (58.3%) were wrongly translated by more than 50% of the participants. Only the false friends argument, compromising, attitude and arrive were translated correctly by 71% of the participants, and the word correspondence received 50% correct equivalence and 50% wrong equivalence (12 translators-to-be in each case). The mistranslation frequency behaved as follows:

Proposing was wrongly translated by 16 of the 24 participants, for 66.7%, who assumed the Spanish word proponiendo as equivalent.

Educated was translated as educado, by 13 translators in training, which represents 54.2% of the total.

Unresolved was translated as no resuelto (91.7% of erroneous translations).

Altered was translated as alterado by 17 trainee translators, which represented 70.8% of the total.

Principal: 14 trainee translators (58.3%) provided the principal equivalent.

Serious and report were translated as serio and reporte (62.5%) of all translations.

In the translated texts, it is evidenced that the equivalents of these words are not consequent with their linguistic context. Despite the fact that translators in training have more translation experience and longer exposure to the English language, these results show that even for the decoding and re-expression of false friends, there is no evidence of a contextual analysis or of the textual typology to be translated, by not taking into account, for example, that words like altered and alterado are semicognates. The participants base the sense-meaning relationship of the false friends on similarities with words in the mother tongue (L1).

The verbalized protocols, in this case, show that there are gaps in the cognitive behavior of these translators-to-be, expressed in the variables of the procedural model. Although the members of this team read the source text before beginning the translation, their understanding was based on the establishment of links between the meaning and the form of the FF, which affected lexical access and, therefore, the rest of the variables assumed in the model.

French-Spanish translation

The translation in this language pair was carried out by 10 of the 24 translators-to-be. The texts in French contained 8 false friends; only pourtant was translated correctly by 60% of the translators tested, and excuse by 50%. On the other hand, the FF procureur and décade were translated as procurador and década by 100% of them, an indicator of the limited knowledge of the equivalents of these words (fiscal and ten-day period). The words contesté, equipage, inversion, and signe were wrongly translated by 7, 8, 9, and 6 of the translators-to-be involved.

This result showed that, as in the English-Spanish translation, the decoding was based on the graphic and phonetic similarity with words in the Spanish language (L1). However, the erroneous translation figures are higher with respect to the English-Spanish test. This is based on the verbalized protocols, in which the "parasitic" translation of most of the FF responds to the etymological proximity of French and Spanish, which conditions the minds of the translators-to-be examined a certain “trust” to assume that similar forms imply similar meanings. Thus, the reflection of the sense-meaning relationship was biased, in this case, by the proximity of languages, so the variables of the procedural model were not corroborated either.

German-Spanish translation

This translation was performed by 14 of the 24 participants involved, who were trained in this pair of languages. The texts to be translated contained the fewest false friends (only four in total), but they generated greater difficulties in lexical-semantic processing, since the false friends zensieren, Konkurs and Differenz were wrongly translated by 100% of the sample examined. Diskussionen, was correctly translated by only three of them (21.4%) and wrongly by 11 (79.6%). This reflects a higher percentage of incorrect translations.

The verbalized data revealed that for the German-Spanish language pair, lexical decoding is more complex. The cognitive gaps occurred in all the steps of the proposed model: the participants involved in the translation task did not read for text comprehension, but proceeded immediately to the translation, and therefore did not diversify the disambiguation pathways, as they were limited only to bilingual dictionaries, and did not compare both texts. The contents of their working memory showed a certain rejection of the translation task, which is based on the etymological and linguistic distance of German with respect to Spanish, and on the complexity that the German language represents for Spanish-speakers.

The previous results showed that the subjects decoded the false friends in the texts in a parasitic way, since in more than 50% of the cases they provided the Hispanic paronym of these FF. The former biases counter-sense and false meanings in the target text, which affects its fidelity with respect to the source text.

In the diagnosis, however, a minority of correct false friend translations were revealed (33% for the English-Spanish false friends, 18% for the German-Spanish false friends, and 24% in French-Spanish). This is because, in some cases, the learner gradually replaced their L1 characteristics with those of the foreign language, which is known as the restructuring continuum, according to Nemster (1971). This contributes to explaining that factors such as exposure time to the target language, to the lexicon under study, etc., allowed some participants to develop this continuum more quickly and efficiently and translate with a lesser degree of influence from the L1.

The transcription of the protocols segmented according to the proposed procedural model, and their corresponding comments are exemplified in Table 1. The general results revealed by the TAPs in each stage are the following:

In the lexical comprehension and access stage, false friends are not identified as vocabulary that potentially produces lexical-semantic ambiguity. Therefore, this phenomenon is not problematized in the translation process.

In the decoding stage, the use of pathways for the disambiguation of false friends is not encouraged, since they have not been identified in the first stage.

In the stage of contextual integration for re-expression, in most cases, the appropriate equivalent for false friends was not offered. Henceforth, deductions can be made that its adequate decoding has not been conducted.

In the textual review stage, the comparison of the sense-meaning relationship in the target context is limited, due to the insufficient detection of breaks in this relationship during the erroneous translation of false friends.

The foregoing reveals ruptures in the cognitive processes for the processing of the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends in the translation and the proposed model is not corroborated.

These results demonstrate the following essential aspects:

The similarities between false friends can influence a parasitic lexical processing in translation, even when the context contributes to the semantic disambiguation, which in turn corroborates the Parasitic Strategy.

In the presence of false friends in the source text, breaks and omission of stages can occur, both in the processing of ambiguous vocabulary and in the translation process.

In summary, the integrated evaluation of the documentary analysis and the triangulation of the applied techniques, revealed the following main insufficiencies:

Insufficient didactic treatment of the dynamics of translation, which hinders an adequate articulation and integration of the linguistic-cognitive and translation perspectives in the process.

Limited link between the logic of the translation process and the cognitive stages for processing the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends, which affects the adaptation of the source text to the source text, and consequently the quality of the training.

Emphasis on the translation product, to the detriment of the strategies for the didactic treatment of the particularities of the lexical-semantic errors produced by false friends, which affects an insufficient use of their linguistic-cognitive potential in the pedagogical practice of translation.

Table 1 - Sample analysis of verbalized protocols. English-Spanish translation

| Stage 1: Orientation | |

|

Protocols "The exercise is well understood" "The texts are short and seemingly easy" "They seem to be fragments of journalistic or literary texts" "there are no unfamiliar words" |

Comments Students have understood what they need to do. Students rate the task as simple, but recognize that it may not be so. Students recognize the textual typology to which the fragments belong, which indicates that this aspect has been worked on in class, and that translators-in-training consider it important to contextualize the translation to that textual typology. Students do not identify unfamiliar vocabulary. |

| Stage 2: Access to the Lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false fiends at the comprehension stage | |

|

Protocols “Los textos tienen cierto grado de dificultad” “encontraste “ |

Comments The students read the text but proceed to translate, ignoring the stage of comprehension of the source text and the appropriation of the meaning and sense of the lexicon. The complexity of the texts is recognized Students react to false analogues on the basis of their graphic similarity. In some cases (e.g., unresolved) they perform a lexicological analysis, by breaking down the word and analyzing the meaning of its parts. However, the assumed meaning does not match the context in which the word is embedded. In general, the comprehension stage has been omitted, as false analogues have not been recognized as such. |

| Stage 3: Selection of lexical-semantic decoding pathways | |

|

Protocols “Creo que será mejor insertar los textos en el google translator, las tecnologías ayudan a agilizar el proceso”. “la traducción de “Serious es serio, verdad?” |

Comments Students base their decoding and selection on the use of google translator, which they recognize as a tool to speed up the process, and not to replace their work as translators. Once again, lexical decision and selection is based on graphic similarities and not on contextual analysis. The resources provided by the target language are not used in the lexical decision, which leads to erroneous equivalences such as correspondence to correspondencia (correspondence of thoughts). |

| Stage 4: Re-expression and integration of words in the target context | |

|

Protocols “Creo que ya terminamos” “¿Se entiende el texto de llegada de la manera en que está?” “Me parece bien” |

Comments No comparison of the target text with the source text is performed, it is reviewed on the basis of the translation product. No in-depth contextual analysis is performed to recognize the lexical-semantic ambiguity caused by the incorrect translation of false friends. |

Source: Authors.

First diagnosis

Results reveal that although there are still translation products with lexical-semantic disambiguation due to false friends at a basic level in 25% in the English-Spanish translation, 40% in the French-Spanish translation and 42.8% in the German- Spanish, there is an increase in translations with lexical-semantic disambiguation due to false friends at an independent level, with respect to the initial diagnosis. This is based on the correct translation of more than 70% of the false friends in 18 translations from the English-Spanish language pair (75% of the total), six translations from the French-Spanish language pair (60% of the total), and eight of the German-Spanish pair (57.1% of the total).

From the cognitive point of view, this result demonstrates the progressive awareness participants acquire about the translation process and the need to integrate it with the linguistic-cognitive, stylistic, pragmatic, cultural analysis, etc., of the phenomenon of lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends, which is revealed in their verbalizations. Thus, a favorable trend is shown in the improvement of its translation performance and in the treatment of lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends, by researching into the features and relationships that characterize this phenomenon, and progressively diversifying the ways of disambiguation, with less teacher intervention.

Second diagnosis

In the English-Spanish translation is revealed that 21 of the 24 translations obtained are categorized in the TI achievement pattern (87.5% of the total), in the French-Spanish translation, 9 of 10 translations reach this achievement pattern (90% of the total), and in the German-Spanish translation, 100% of the texts also respond to this achievement pattern.

This result is a consequence of the systematization of a linguo-didactic logic, which favors the strengthening of the autonomy, level of analysis and coherent organization of the translation process by the translators in training in terms of the understanding of the source text, the diversification of ways for the lexical decision and the re-expression and conscious and argued contextual integration that justifies the fidelity of the translation product with respect to the source text. This is evidenced in the protocols verbalized, in which a higher level of awareness of the procedural nature of the translation is demonstrated, and of the most efficient ways to deal with the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by FF.

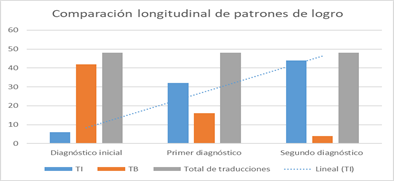

Data analysis revealed a satisfactory development to the same extent that the strategy is systematized over time, which is an indicator of its relevance in the translators training process, as expressed in the following graph, where TB responds to the level of performance of translation with lexical-semantic disambiguation by false friends at a basic level and TI to translation with lexical-semantic disambiguation by false friends at an independent level. (Figure 1)

Source: Authors

Source: AuthorsFig. 1 - Longitudinal comparative analysis of performance levels, before and after the application of the didactic strategy proposed

Despite the predominance of the TI performance level, it did not behave in the same way in the three language pairs analyzed. This is justified by the particularities of the pair of languages, in those of their learning, and in the effect of linguistic-cognitive awareness produced by the application of the proposed instrument in translation classes.

Consequently, the TI achievement pattern is higher in the German-Spanish language pair, since the participants were more aware of the linguistic distances between them, and emphasized more on the diversification of disambiguation pathways. In the French-Spanish language pair, the etymological proximity of these languages prompted the trainee translators to conduct a deeper contextual analysis, based on the awareness that the proximity of languages does not imply analogies of meanings and senses between formally similar words. In the English-Spanish pair, the translation experience and the longer exposure time to the English language with respect to the French and German languages still condition cognitive "confidence", and therefore more erroneous translations of false friends are revealed with respect to the other two language pairs analyzed.

Conclusions

Despite being mostly used in psycholinguistic research, Think Aloud Protocols contributes to offering important results for the study of mental procedures during the translation process, since the protocols verbalized by the translation subjects offer valuable information not only about the processing of errors and translation difficulties, but also about guidelines for their subsequent treatment.

The exemplification of the use of this technique in the study of the lexical-semantic ambiguity produced by false friends in translation, through different stages of a diagnosis, corroborated its usefulness to determine the cognitive processes performed by translators in training, in the approach and processing of the translation error. Likewise, it allowed revealing the changes that occurred in this processing after the application of a didactic strategy for the treatment of the error.

The previous sets the foundations for the use of the TAPs technique in research on communicative mediation processes, where the analysis of the contents of working memory is relevant for obtaining research results.