INTRODUCTION

Status Epilepticus (SE) has been described by the ILAE as “a single epileptic seizure of > 30 − min duration or a series of epileptic seizures during which function is not regained between ictal events in a 30-minute period” (Epilepsy, 1993). In the 2015 League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) special report mentioning the SE de- finition, a more general concept was offered by Trinka et. al (Trinka et al., 2015). The definition provided by Trinka add a two operational dimensions to the conceptual approach, the length of the seizure and the time points t1 (beyond which the seizure should be regarded as “continuous seizure activity”) and t2 (time of ongoing seizure activity after which there is a risk of long-term consequences).

Similarly to the rest of the epileptic disorders, SE can be classified regarding the seizure onset as focal or generalized. According to the 2016 American Epilepsy Society report, given the signs and symptoms the SE can be divided in three main categories (1) convulsive SE, (2) nonconvulsive SE and (3) repeated partial seizure (Glauser et al., 2016). A more extensive classification is presented in (Trinka et al., 2015), which proposes to classify the seizures in terms of two physical features, (1) the presence or absence of prominent motor symptoms and (2) the degree (qualitative or quantitative) of impaired consciousness. The SE with prominent motor symptoms and consciousness impairment can be defined as convulsive SE (CSE) as opposed to nonconvulsive SE (NCES).

SE and NCES are associated with severe irreversible brain damage and poor outcome. Delaying the diagnosis, and in consequence, the treatment may increase the mortality rate (Hirsch and Brenner, 2011). The prompt recognition of the seizure activity will determine the treatment effectiveness; The faster the diagnosis is made and the shorter the duration of the seizures, the more effective the treatment and the better the outcome (Hirsch and Brenner, 2011). The CSE recognition is evident given the recurrent overt convulsive seizures that characterize it. On the other hand, recognizing NCES is harder given the lack of physical signs. However, if CSE is untreated or inadequately treated, it progresses from overt convulsions to nonconvulsive (Chang, 2005).

The role of the EEG in the diagnosis and classification of epileptic disorders and seizure types is well-established (Koutroumanidis et al., 2017; Tatum et al., 2018). The most common use of EEG monitoring is to determine whether a patient with abnormal synchronous brain activity is having epileptic seizures. Furthermore, the EEG may indicate electrographic evidence of seizures even if these are nonconvulsive.

Monitoring SE during treatment as well as monitoring EEG in intensive care, critical care, or emergency settings may provide clinical evidence relative to the presence, amount, and response to treatment when seizures or status epilepticus are considered (Tatum IV, 2014). Several studies have found that following seizures or SE, especially with mental status impairment, many patients still have NCES or NCSE, even after being treated (Chang, 2005).

Originally, long-term EEG monitoring was used to identify the electrographic activity of clinically recognizable seizures. Therefore, for the monitoring to be successful, the events had to have symptoms that could be noticed by the patient or the medical staff. Hence, it was not possible to diagnose events with minor symptoms (e.g., NCES) with the EEG. To detect subtle events, the EEG data was recorded for 24 hours or more. Then, it was manually reviewed by the clinician. The manual review of such amount of data is tedious and time-consuming labor. Usually, a trained technologist performed a first review labeling events of interest for the doctor to complete the final review (Chang, 2005). Nowadays, a seizure detection algorithm makes the preliminary screening of the data, making the process more time efficient and accurate.

Many efforts have been made in the seizure detection field (Orosco et al., 2013), however, very few of them for NCES detection (Ansari and Sharma, 2016). Most of the existing automated seizures detection algorithms, designed for epilepsy monitoring, have been extensively trained and validated on seizures obtained from patients with convulsive seizure disorders, without other brain damage. However, seizures from brain-injured patients are considerably different. Ictal activity from comatose or brain-injured patients is often less organized, slower, with longer duration and without clear on- and off-set (Schomer and Da Silva, 2012).

The proposed methods for NCES detection published until 2015 are summarized in the work of Ansari and Sharma (Ansari and Sharma, 2016). These methods can be split according to their principal aim: those that detect NCES without coma/stupor (i.e. absence seizures) (Kollialil, et al., 2013); (Liang et al., 2010) and the ones that perform the NCES detection on ICU patients (Khan et al., 2012; Varshney et al., 2013; Sharma et al.,2014). The major drawbacks of the NCES detection proposed methods are related to the arbitrary nature of the selected thresholds for performing the detection. Seizure duration and the number of channels affected by the seizure activity are the most popular criteria for thresholding (Khan et al., 2012; Varshney et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2014). Seizures are not detected if they are too short in time or too localized (just a few channels affected by the seizure activity). NCES are heterogeneous across patients, the patterns present in the EEG will depend on the etiology of the seizure. Therefore, a threshold which works for one patient will not necessarily work for another. Also, there are more meaningful ways to describe the seizure’s spatial localization than the number of channels; that is, the seizure topography.

In (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018) a patient specific method is proposed that mitigates the need of thresholds to detect the NCES. This method identifies the NCES by exploiting the similarity between the first NCES detected by the physician on the EEG and the rest of NCES in the recording. The features explored are obtained by means of multiway analysis of the EEG signal represented as a third order tensor X ∈ R(F ×T ×C h), where the different modes represent frequency, time and channels. The tensors are computed by expanding EEG segments using the Hilbert Huang Transform (HHT). A rank one canonical polyadic decomposition (CPD) is applied to decompose the constructed tensors. Then, the channel mode signature is used as a feature to detect the NCES by means of a radial basis support vector machine (SVMRB). The method achieved average sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy values over 98 % during the testing in continuous EEG recordings, proving to be robust against artifacts. The achieved false positive rate values suggested a low the number of non-seizure events classified as seizures. Most of these misclassifications are due to the appearance of long duration paroxysms or a large number of successive spikes in the EEG. These events, are long enough to resemble a seizure but are too brief to be classified as a seizure according to the physician’s criteria. False positive detections also occur at epochs with pre-ictal or post-ictal EEG activity.

In this paper, we propose a supplementary method based in partial least squares (PLS) to improve the identification of the NCES patterns of the method proposed in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018) in dubious EEG segments. The method here proposed, as the proposed in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018) uses the channel mode signatures to classify EEG segments as seizure or seizure free. The final decition about a segment is given by the coincidence of the classification of both methods.

METHODS AND TOOLS

EEG Data

The EEG data were obtained from 14 recordings, 9 from ambulatory and 5 from ICU medical settings. The ambulatory EEG data were collected as part of patients’clinical assessment at the Epilepsy Unit of the CIREN. The ICU data were collected at the ICU of the Clinical Surgical Hospital “Hermanos Ameijeiras”.

Data were anonymized prior to their use in this study. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committees of the CIREN and “Hermanos Ameijeiras”Hospital respectively.

Since the patients come from different hospitals and areas, the acquisition protocol shows some differences; yet the sampling rate for all recordings is 200H z. The number of electrodes used for the recordings varies between 8 and 19. In all cases, the electrodes were placed according to the 10-20 montage system.

All patients in the study are adults (ages ranging between 18 and 57 years old) with various brain disorders that present NCES. The visual inspection and labeling were performed by three neurophysiologists. The recordings duration raged between A total of 139 seizures have been registered, all of them NCES according to the neurophysiologist’diagnosis (55 with coma/stupor).

Partial Least Squares

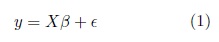

Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS) is a linear classification technique that generalizes and com- bines features from partial least squares regression with the discrimination power of a classification technique. Given the feature matrix  (with s samples and p features) and its corresponding label vector y ∈ {±1} with size s (both mean-centered), partial least-squares (PLS)’main purpose as in multiple linear regression, is to build a linear model in the following way (Brereton and Lloyd, 2014),

(with s samples and p features) and its corresponding label vector y ∈ {±1} with size s (both mean-centered), partial least-squares (PLS)’main purpose as in multiple linear regression, is to build a linear model in the following way (Brereton and Lloyd, 2014),

where  is the regression coefficient vector, and

is the regression coefficient vector, and  is a noise term for the model.

is a noise term for the model.

PLS-DA attempts to disclose the main latent variables in X that permit to predict y and describe their joint structure. If y is a vector and X is full rank this can be done by a classical multi-linear regression method. But when s is smaller than p, X is likely to be singular and the regression approach is no longer feasible. Several strategies are proposed to deal with the singularity of X, one of them is to drop some predictors. For choosing which features to delete, PLS uses principal component regression (PCR).

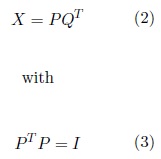

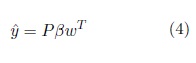

PCR performs the PCA of X and then uses the resulting PC of X as the independent variables of a multiple regression model to predict y. In contrast to PCA, which decomposes X to find the components that best describe X , PLS decomposes X and y simultaneously to find the components in X that best predict y (la- tent vectors)(Abdi, 2010). The selected latent vectors must maximize the covariance between X and y. The independent variables are then computed as (Brereton and Lloyd, 2014),

where I is the identity matrix. By analogy with PCA, P is called the score matrix and Q is called the loading matrix. The y is estimated as

w is the ‘weight vector ’. A more detailed explanation of how to obtain the w vector, as well as the implemen- tation of PLS-DA, can be found in (Abdi, 2010; Brereton and Lloyd, 2014).

Proposed Methodology

Each recording was divided in segments (epochs) 3s duration, without overlapping. All epochs were transformed in the time-frequency domain, using the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT). The HHT by means the empirical mode decomposition (EMD) (Huang et al., 1998), decompose a signal in a number of narrow-band components, modulated in amplitude and frequency called ‘intrinsic mode functions ’(IMF). Afterwards, the signal can be reconstructed in the way,

where imfk is the kth IMF of the signal, and r is the residue (Huang et al., 1998). This decomposition is adaptive and based on the local properties of the signal which allows its use for the analysis of nonlinear and nonstationary signals as the EEG. The HHT resolves time × f requency events with high temporal resolution and thanks to the adaptive nature of the EMD provides a more meaningful physical interpretation of the underlying EEG data.

After the transformation, for each EEG channel an IMF matrix is obtained with f requency scales in the rows and time scales in the columns. This matrices are staked one after the other to form a 3r d from every epoch with modes f requency × time × channels. A tensor is a multidimesional array in wich the number if indexes of their elemets correspond with the tensor order. e.g. a vector is a first order tensor ans their elements have one indice, a matrix is a second order tensor ans ther elements have two indices, a third order tensor is reperesented as a cube, and their elemts have trhee indices (see Fig. 1). Higher order tensors have a more complex graphical representation but alwais the number of indices needed to access individual elements will correspond to the order of the tensor.

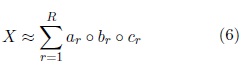

The tensors are decomposed using the Canonical Polyadic Decomposition (CPD). The CPD decompose a tensor in a sum of rank one components that describes the original data in the following way,

Where  are nonzero vectors that define the mode-n signature, n = 1, . . . , N (for N = 3).

are nonzero vectors that define the mode-n signature, n = 1, . . . , N (for N = 3).

From these decompositions the signatures from each mode of the tensor are obtained. These signatures are sup- posed to describe the behavior of each mode constrained by the others. In this implementation only the channel mode is used since it was pointed out as the best choice to perform the NCES detection in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018). This mode describes the topographic behavior in each EEG segment. Fig. 1 show the tensorization and decomposition process. It has been shown that tensor decompositions of multiway EEG representations can extract seizure sources and accurately characterize the seizure pattern (Hunyadi et al., 2014). The mul- tiway analysis exploits the EEG high dimensional structure by analyzing its spectral, temporal and spatial properties simultaneously.

The channel mode signatures from the EEG epoch from the beginning of the EEG recording to the end of the first seizure identified by the physician and their corresponding labels, are used to train a PLS model. The rest of the EEG recording is used to test the trained model. The method here proposed is patient specific. Which means, that one model is trained for each patient.

PLS model is tested individually in all cases available in the database in order to asses and compare it performance with the SVM model proposed in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018). After, both model are combined to perform the NCES detection. The EEG epoch for which the models disagree are assigned to the class pointed out by the model with the highest classification probability.

The models performance is evaluated in terms of specificity, sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV)computed as,

where

TP |

is the number of positive samples correctly classified as such |

FN |

is the number of positive samples classified as negative samples. |

The specificity is defined as,

Where

FP |

is the number of negative samples classified as positives |

TN |

is the number of negative samples correctly classified as such. |

PPV |

is termed as, |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results obtained from the PLS model are slightly inferior to the ones obtained with the SVM as can be observed in Table 1. This indicate that the SVM model proposed in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018) is more adequate to perform the NCES detection. However, the combination of the two models results in a improvement of the overall performance of the separate models obtaining a 99.4 % of specificity, 99.5 % of sensitivity and a 90.8 % of positive predictive value.

The PLS model in the worst case, displayed an execution time of 1,8s for the training step and 0,042s for the classification. Regarding the computational efficiency, the PLS model outperformed the SVM model with displayed an execution time of 3,3min for the training step and 3s for the classification step. All performance tests are performed on a computer with a processor Intel Core-i3 at 1,70H z with 8GB of RAM. The average detection latency for PLS is 2,7s compared to 5,4 achieved by SVM. The average latency for the models combination was 1,7s.

Table 1 Specificity (Spc), Sensitivity (Sen), and Positive Predictive Value (PPV) scores obtained for the SVM and PLS models, and the combination of these two.

As expected, the number of misclassified epochs due to long paroxysm and spiking decreased for the SVM- PLS combination compared to the individual models performance. However, the PLS and SVM models as the individual models, is less effective when the NCES morphology evolves over time. As explained before, the models are trained considering only the first seizure. As consequence, if the seizure EEG pattern morphology changes for the later seizures, the classifiers become less accurate. Update the classifier with the new patterns that may appear could help to improve this shortcoming.

Some classification errors are detected due to pre-ictal activity appearance in some epoch. All models displayed the same results for these epochs. The pre-ictal activity is not labeled as seizure activity in the available data. However, the post-ictal activity it is. Given the resemblance between the prei-ctal and pos-tictal activities it is expected that the classifiers commit such errors, since the posictal patterns are incorpored in the training as seizure activity. An alternative solution must be proposed to rule out epochs with pre-ictal activity. A pre-classifier could be trained to label such epochs in order to warn the posterior model about this kind of activity.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduced an alternative classification model to improve the NCES detection method proposed in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018). The PLS model here proposed does not improved the performance achieved in (Rodr´ıguez Aldana et al., 2018) with a SVM. However, the combination of the SVM with the PLS model resulted in an improvement of the overall performance of both methods individually obtaining values of specificity and sensitivity over 99 %.

The methods demonstrated to be less accurate when there is an appreciable evolution of the seizure morphology over time, and when the EEG epochs correspond to pre-ictal activity. The classifier updating and the pre-ictal activity labeling could help to solve this drawback.

The methods here proposed showed potential to be used in routine clinical environments to perform NCES detection since the computational cost displayed during the test was lower or equal to chosen analysis window.