Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Cooperativismo y Desarrollo

versión On-line ISSN 2310-340X

Coodes vol.9 no.1 Pinar del Río ene.-abr. 2021 Epub 30-Abr-2021

Original article

Overview of international tourism competitiveness in Central America and the Caribbean area

1 Universidad de Pinar del Río "Hermanos Saíz Montes de Oca". Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas. Departamento de Matemáticas. Pinar del Río, Cuba.

2 Universidad de Sevilla. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales. Departamento de Economía Aplicada II. Sevilla, España.

Tourism is considered the fundamental economic activity for many economies worldwide and is the fastest growing activity in the Caribbean area. With markets in constant change, the competitiveness of tourism destinations is key to differentiate between good tourism management and inefficient management. The most popular international index and the most comprehensive is prepared by the World Economic Forum, which does not include Cuba or several Central American and Caribbean countries. The present work tries precisely to bring the reader closer to the concepts of tourism competitiveness, as well as to the Tourism Competitiveness Index and the situation of Central American and Caribbean countries in it, using the dialectic method as a guideline in the theoretical analysis of the research.

Keywords: tourism competitiveness; tourism; tourism ranking

Introduction

Tourism has been increasingly used as a way to overcome market constraints and supplant the decline of traditional export sectors. It avoids problems of scale because the demand for the product is essentially imported into the small economy (Croes, 2016).

The definition of tourism has evolved over time, but since the end of the last century, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has conceptually associated it with those activities carried out by people during their trips and stays in places other than their usual environment, for a consecutive period of less than one year for leisure, business and other purposes.

If the concept of tourism has evolved to the clear conceptualization of the UNWTO, conceptualizing tourism competitiveness or the competitiveness of a tourist destination has followed a similar path. Given the nature of the term, beyond a concept, the authors have focused on quantifying it and the way it is measured has given rise to the creation of numerous models over the decades, without there being much consensus on the predominance of any one, rather it is a work in progress in which each research makes a contribution based on previous research.

From an international point of view, the competitiveness of a tourism destination can be defined as the ability to attract non-resident tourists, but this definition cannot be applied without an analysis of traditional performance indicators since this activity is a service where the consumer must be transferred to the place of production. Then, to perform a diagnosis of tourism competitiveness, it is important to consider the impact that tourism activity has on the region to be analyzed and the period in which this impact is measured (de la Peña et al., 2019).

Despite such diversity of opinions, a little more than a decade ago, international organizations related to tourism created an index to measure tourism competitiveness at the international level, scoring countries through a group of indicators that were already collected.

Today, this index, called the Tourism and Travel Competitiveness Index (TTCI), is compiled by the World Economic Forum (WEF) and has become the most popular index. Among its main advantages is that it is consistent over time as it is currently biannual and allows comparing a diversity of countries because it collects the same indicators from all of them (Andrades & Dimanche, 2017).

The purpose of this text is to review the evolution of the concept of tourism competitiveness, as well as to present the TTCI and emphasize the situation of Central American and Caribbean countries in this regard.

Materials and methods

In this research, secondary sources of information were used to determine the current state of international tourism competitiveness in the Caribbean area, in addition to the comparative analysis of the different models that refer to the object of study in this case: the competitiveness of tourist destinations.

As a guiding method in the theoretical analysis of the research, the dialectical method was used, determining an evolution in the phenomenon. Documentary analysis and analysis and synthesis were also very useful to establish continuity and rupture, present in the different models studied.

For the quantitative analysis of the data and the elaboration of graphs that allow a visual explanation of the phenomenon and its components, the Python programming language in its version 3.8 and the Spyder development environment platform in its version 4.1.4, both technologies currently under free software license, were used.

As materials, data contained in the World Tourism Barometer reports from 2013 to 2019, as well as the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Reports from their inception to date were used.

Results and discussion

Tourism competitiveness

Conceptualizing the competitiveness of a tourism destination brings controversy and confusion due to the scope and complexity of the concept and its multifaceted nature that includes different dimensions, but it has been a task of great interest in the literature over the last decades (Salinas Fernández et al., 2020).

Several models of tourism competitiveness have been developed in the literature. Based on the distinction between comparative advantage and competitive advantage, Crouch and Ritchie (1999) proposed a theoretical model that is neither predictive nor casual, but simply a conceptual model which fundamental purpose is to use highly abstract concepts and relationships to explain the factors that determine tourism competitiveness.

In its conceptual model, the competitiveness of the tourist destination is conditioned by two factors, the competitiveness of the region and global competitiveness. The first is the immediate environment to which each destination must adapt in order to create links and work with the different agents operating in the tourism sector (e.g., tour operators, travel agencies, financial institutions, etc.).

The second consists of global forces that change the composition and nature of the destination, such as the growing awareness of environmental welfare, demographic changes in the main tourist source markets, or the increasingly complex relationship between technology and humans. Crouch and Ritchie (1999) warned of the changes that the environment is rapidly undergoing and recommended that tourism managers adapt to these changing times.

In the work of Kim et al. (2001), a new model of tourism competitiveness is proposed that considers four sources of competitiveness:

Primary sources of competitiveness include issues (politicians, employees and travel agents), environment and resources (historical, cultural and natural)

Secondary sources cover tourism policy, destination planning and management, investment in the sector, and tourism taxes and prices

Tertiary sources of competitiveness are tourism infrastructure, visitor accommodation, resource attraction, advertising and staff qualifications

Finally, the quaternary sources where the result of the three previous sources is considered. They refer to tourism demand, employment created by the sector, "tourism performance" (growth rate, balance of payments of the sector, the sector's contribution to the GDP of the country or region) and tourism exports

These sources of competitiveness are the tourism products obtained from different inputs (productivity of the sector), and therefore constitute a direct indicator for the evaluation and comparison of competitiveness. The model of Kim et al. (2001) explains that each source of competitiveness should have different weightings with quaternary sources always receiving a higher weighting.

In Dwyer and Kim (2003), the authors proposed a tourism competitiveness model, based on the earlier model of Crouch and Ritchie (1999), but used to determine the competitiveness of a country as a tourist destination, although it can also be applied to regions, provinces and cities. They clearly distinguish between "inherited resources" and "created resources" and consider that these two types of resources, together with "complementary factors and resources", have their own identities.

These three elements determine whether a destination is attractive or not and the success of the destination's tourism industry must be based on them. Therefore, they conclude that these elements constitute the basis of tourism competitiveness.

However, in the Dwyer and Kim (2003) model, once again, there is a lack of justification as to which factors belong to which source. For example, why does tourism infrastructure constitute a tertiary source of competitiveness? Something similar applies to destination subjects (tourism stakeholders) which, although important in a competitiveness model, cannot be justified as a tertiary source. In their model, "destination management" and "demand conditions" constitute the so-called local conditions, which can limit, modify or strengthen the competitiveness of a destination.

"Destination management" refers to all those factors that strengthen the attractiveness of local tourism resources and adapt the destination to its particular conditions, including actions related to tourism marketing management, tourism policy, planning and development, and environmental management.

"Demand conditions" refer to tourism knowledge, tourist perceptions and preferences, all of which determine the competitiveness of the tourism destination. Therefore, while the competitiveness of a destination depends on both "base" and "local" conditions, it is, in turn, a determinant of the socioeconomic "prosperity" of the destination. In fact, it is an intermediate objective to achieve the ultimate goal, which is the socioeconomic well-being of residents (Parra López & Oreja Rodríguez, 2014).

Dwyer and Kim (2003) propose a wide range of indicators, both objective and subjective, of tourism competitiveness, as well as indicators of socioeconomic prosperity (i.e., employment levels, per capita income, economic growth rate). This makes it evident that, regardless of the tourism competitiveness model used, competitiveness has a character that is not directly observable and its quantification requires the use of indirect indicators.

Competitiveness is a phenomenon that cannot be characterized only by objective indicators (those related to quantitatively quantifiable aspects) or only by subjective indicators (mainly tourism-related perceptions). In 2001, the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) introduced the Competitiveness Monitor covering almost 200 countries and using eight broad indices, each constructed from several competitiveness indicators.

A comparative analysis of the indicators proposed by Dwyer and Kim (2003) and those of the WTTC reveals that there is no consensus on which indicators should be used to quantify tourism competitiveness and, furthermore, that the measurement of tourism competitiveness involves enormous difficulties since its measurement is, to a large extent, conditioned by the indicators used.

More recently, Hong (2009) refers to the Crouch and Ritchie (1999) model as the most important work on the analysis of tourism competitiveness and attempts to improve its results. Hong (2009) aims to resolve some of the weaknesses in the Crouch and Ritchie (1999) model, arguing that the order of factors and categories of variables should be treated according to their importance. He also states that the Crouch and Ritchie (1999) model does not analyze the interaction between comparative and competitive advantages and tourism competitiveness.

Finally, Hong (2009) indicates that many of the factors in the Ritchie and Crouch model are qualitative rather than quantitative. Therefore, the proposed model and methodology weigh and rank the importance of each factor and indicator with respect to the relevance of its contribution to the destination's competitiveness.

A new attempt to measure tourism competitiveness is had with the construct "competitiveness of tourist areas", created by Parra López and Oreja Rodríguez (2014) which includes elements that reflect the variety of conceptual components highlighted by Crouch and Ritchie (1999), Kim et al. (2001) and Dwyer and Kim (2003).

Table 1, provided by Parra López and Oreja Rodríguez (2014) shows the main advantages and disadvantages of tourism competitiveness models, along with comments on their competitiveness indicators. The design of the different measurement models to date can be classified into two groups. The first group uses objective data that refer to the different concepts of competitiveness: these cannot be combined with each other as they differ conceptually.

The use of econometric models to obtain aggregate measurements, based on a series of assumptions, allows comparable results to be obtained. However, the second group of instruments uses subjective data, based on the methodologically invalid assumption that the scores given to the items (competitiveness factors) are their measures and can be summed. In fact, the scores are ordinal values, without the required interval properties in the summation process; therefore, the results obtained are neither valid nor reliable.

Table 1 Models for measuring competitiveness

| Model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Crouch and Ritchie (1999) | It proposes quantitative indicators | Conceptual model based on the qualitative concepts of competitiveness and highly abstract relationships. All indicators are assigned the same weight. |

| Kim et al. (2001) | It proposes quantitative and qualitative indicators of competitiveness. | It does not justify the differences among primary, secondary and tertiary sources of competitiveness. All indicators are assigned the same weight. |

| Dwyer and Kim (2003) | It differentiates between the competitive base and the local destination. It proposes quantitative (or strong) and qualitative (or soft) indicators of tourism competitiveness. | All indicators are assigned the same weight. |

| Gooroochurn and Sugiyarto (2005) | It gives different weights to each factor. Then it compares the competitiveness of different destinations and develops a ranking according to their degree of competitiveness. | The final results are not consistent with the reality of the destinations. The weight given to the indicators may be questionable. |

| Hong (2009) | It uses indicators and variables proposed by other authors in their models, which provides reliability. Weighs and prioritizes the importance of each factor and indicator with respect to its relevance in contributing to the tourism competitiveness of the destination. | The questionnaires were sent to academic researchers with experience in the field and to government officials working in tourism. It would be interesting to contrast in the study all those involved in the tourism sector to complete the perspective. |

Source: Parra López and Oreja Rodríguez (2014)

In short, how competitive a territory can be in the market, which will depend on many circumstances and, therefore, on the degree of competitiveness of a destination, may not be a significant indicator of the efficiency of its economy or the level of well-being of its population.

In fact, a destination may base its competitiveness on low wages and low profits or on the availability of natural resources that are unique in the world; or, alternatively, on the existence of high productivity that allows higher wages and excellent profits or on an improvement in the quality of services or, in general, of the tourist experience.

In both cases, these tourist destinations would be competitive, but the meaning (and consequences) of that competitiveness would be radically different (Pulido Fernández & Rodríguez Díaz, 2016).

Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index

The most notorious of the synthetic indicators for tourism competitiveness is perhaps the TTCI, a synthetic indicator, designed to compare countries at a global level that is published periodically by the WEF in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report. The purpose of this indicator is to evaluate the factors and policies that make a destination attractive for international tourism (Gómez Vega & Picazo Tadeo, 2019).

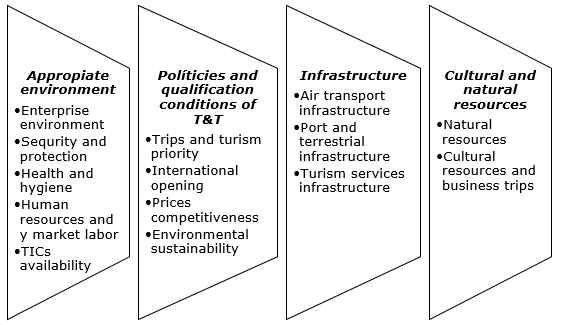

Since 2007, the WEF has created the TTCI to continue the work that the WTTC had been doing until then, taking as a basis many of the data collected by the same organization. This index, produced by the same organization, has its framework in 4 sub-indices (Calderwood & Soshkin, 2019) (Fig. 1) that try to cover all aspects of the travel and tourism (T&T) sector.

Each sub-index consists of several pillars, 14 in total, which in turn summarize a large number of indicators, 90. The detailed explanation of each of these pillars can be found in the 2019 WEF report and is fundamental to understanding the TTCI.

Source: Own elaboration based on the WEF report year 2019

Fig. 1 Sub-indices used to measure competitiveness by the WEF

The enabling environment sub-index captures the general conditions necessary to operate in a country and includes 5 pillars:

1. . Enterprise environment (12 indicators): this pillar captures the extent to which a country has an enabling policy environment for enterprises to do business

2. . Security and protection (5 indicators): security and protection are critical factors that determine the competitiveness of a country's T&T industry

3. . Health and hygiene (6 indicators): Health and hygiene are also essential to T&T's competitiveness. Access to clean water and improved sanitation is important for the comfort and health of travelers

4. . Human resources and labor market (9 indicators): high quality human resources in an economy ensure that the industry has access to the employees it needs

5. . ICT (Information and Communications Technology) availability (8 indicators): online services and business operations are increasingly important in T&T, as the Internet is used to plan itineraries and book travel and accommodation

The T&T enabling policies and conditions sub-index captures specific policies or strategic aspects that most directly impact the T&T industry and includes 4 pillars:

6. . Travel and tourism prioritization (6 indicators): the extent to which the government prioritizes the T&T sector has a significant impact on T&T competitiveness

7. . International opening (3 indicators): the development of an internationally competitive T&T sector requires a certain degree of openness and travel facilitation

8. . Price competitiveness (4 indicators): lower travel-related costs in a country increase its attractiveness for many travelers, as well as for investment in the T&T sector

9. . Environmental sustainability (10 indicators): the importance of the natural environment in providing an attractive location for tourism cannot be overstated, so policies and factors that enhance environmental sustainability are an important competitive advantage in ensuring a country's future attractiveness as a destination

The infrastructure sub-index captures the availability and quality of physical infrastructure in each economy and includes 3 pillars:

10. . Air transport infrastructure (6 indicators): air connectivity is essential to facilitate travelers' access to and from countries, as well as movement within many countries

11. . Terrestrial and port infrastructure (7 indicators): the availability of efficient and accessible transportation to key business centers and tourist attractions is vital for the T&T sector

12. . Tourism services infrastructure (4 indicators): the availability of accommodation, resorts and entertainment venues of sufficient quality can represent a significant competitive advantage for a country

The Natural and Cultural Resources sub-index captures the main "reasons to travel" and includes 2 pillars:

13. . Natural resources (5 indicators): countries with natural assets clearly have a competitive advantage in attracting tourists

14. . Cultural resources and business travel (5 indicators): a country's cultural resources are another critical driver of T&T competitiveness

It is worth noting that the sub-index that measures the most indicators is the enabling environment with 40 indicators in total, including the enterprise environment, which measures 12 indicators, the pillar that summarizes the most indicators, two more, even, than the Natural and Cultural Resources sub-index.

The indicators measured can be qualitative (perception) or quantitative. Those quantitative indicators come from public data from available sources, international organizations and tourism-related institutions and experts, for example: the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the WTTC, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) (Calderwood & Soshkin, 2019).

On the other hand, qualitative indicators measure the perception of certain aspects through surveys of CEOs and industry leaders in each of the countries included in the ranking. The surveys provide important data on variables that are very difficult to measure, such as the quality of the natural environment. For this task, the WEF relies on organizations present in each country being measured, ranging from governmental institutes to local universities.

With T&TCI, a kind of consensus is reached among different researchers as previously models prioritized visitation levels and market share and these may not be accurate or appropriate measures of tourism performance to assist industry professionals in their day-to-day decisions to achieve sustainable competitiveness. In addition, it can be seen as a source of knowledge for business and industry decision making related to the travel and tourism sector.

Identifying the best performance through the comparison that this ranking provides is the most important part of the benchmarking process and being at the top of the T&TCI ranking can certainly provide a good reputation which is a valuable intangible asset for the country.

Despite this, the quality of timely, accurate and accessible data is crucial in tourism planning and development. This is not only because of the need to promote quality tourism products to keep up with increasing competition, but also because of its impact on government budgets in developing countries. Some authors argue that an increasingly complex set of competitiveness indicators, in global indices such as the T&TCI, does not take into account the context or descriptors of many destinations such as some small islands.

The most relevant criticism of this index is that the indicators, while illustrating the processes or concept in question, cannot measure the concept directly. Doctor density, hospital beds, timeliness of data delivery, quality of roads, quality of rail infrastructure, Internet users, telephone lines, ticket taxes and airport charges, extent and effect of taxes, primary education enrollment, etc., all point to, but do not measure competitiveness directly.

Competitiveness in the region

The insular Caribbean is comprised of Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Bahamas, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. Tourism is the dominant economic activity in the Caribbean region, which is the largest recipient of tourism in the world.

The establishment of tourism as a key economic activity was initially driven by a post-independence economic restructuring in the region, moving from an agriculture-based economy to one based on services and manufacturing. This restructuring was considered necessary to address declining competitiveness in traditional sectors (agriculture, for example) and a need to build competitiveness in non-traditional areas. It is estimated that in 2009 tourism accounted for 14.5% of the region's GDP, the highest contribution in the world, and generated 11.9% of employment.

The Caribbean is the most tourism-dependent region in the world, yet it is not predicted to have a bright future compared to the Asian region. The high dependence of most Caribbean countries on tourism makes understanding, analyzing and improving tourism competitiveness imperative for the region. As early as 2005, the World Bank recommended to the countries of the Caribbean Community (Caricom) not to base tourism growth expectations on global growth in the sector, but to focus on increasing competitiveness.

To analyze the international visibility of the region's tourism competitiveness, it is necessary to go to the WEF report. During the years 2013 and 2015, Haiti and Puerto Rico were included in the ranking, absent already in the 2017 report. The global positions for the countries belonging to the region are shown in the table:

Table 2 Global positions of the Central American and Caribbean countries

| Country | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbados | 58 | - | ||||||

| Costa Rica | 42 | 42 | ||||||

| Dominican Republic | 86 | |||||||

| El Salvador | 91 | |||||||

| Guatemala | 86 | 86 | 99 | |||||

| Haiti | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Honduras | ||||||||

| Jamaica | ||||||||

| Nicaragua | 99 | 92 | 92 | 91 | ||||

| Panama | ||||||||

| Puerto Rico | - | 45 | - | - | ||||

| Trinidad and Tobago |

Source: Own elaboration

Of the 20 countries that make up the region, at best, only 12 were present, which means that 40% of the countries are not measured in the most representative international instrument for the competitiveness of the T&T sector, something that has no cause in any of the WEF reports and that lacks explanation in an area so dependent on tourism. It may be because the T&TCI method seems intractable, the data requirements are difficult and, at the same time, impossible to produce as explained by Croes and Kubickova (2013) who analyzed this issue.

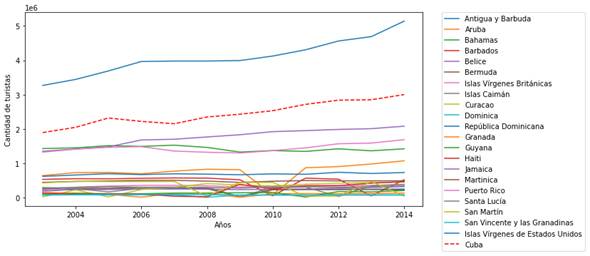

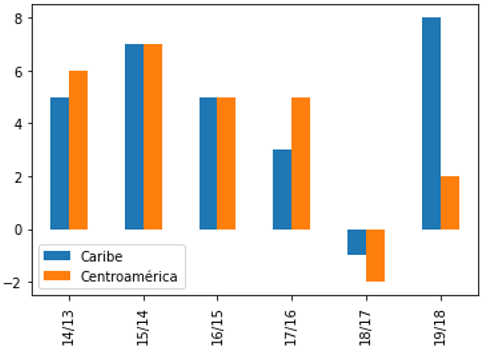

Despite this, the number of international tourists has increased in the region, decreasing a little in 2018, but in 2019, the percent change from the same previous period, from 2014 to 2019 of international tourist arrivals, is shown in figure 2.

Source: Own elaboration based on World Tourism Barometer, 2019 (https://www.unwto.org/world-tourism-barometer-2019-nov)

Fig. 2 Percentage change in tourist arrivals from one year to the next

The problem to be faced in order to increase the competitiveness of the Caribbean is inter-island transportation, which requires attention since transportation markets have been dominated by monopolies (Briceno Garmendia et al., 2015). The development of two lines is recommended to address connectivity and competitiveness issues: one in the north and one in the south. The development of a regional connector in a central Caribbean island should also be considered. Critical to this process is collaboration between independent states.

The study bases the recommendation on the 2007 San Juan Agreement, signed by the ministers of tourism and transport of the member states of the Caribbean Tourism Organization who identified the need for a regional approach to ensure sustainability along with harmonization of aviation policies in the region (McLeod et al., 2017).

Situation in Cuba

To understand how Cuba's tourism competitiveness has behaved, it is necessary to review the development of tourism on the island. Tourism re-emerged in Cuba in the 1990s as a sector prioritized for foreign investment and from its beginnings showed astonishing gains, for example, the number of tourists grew by 82% from 1990 to 1994, fueled by a large influx of Europeans and Canadians (Simon, 1995). In the same work, a chronological analysis can be found (Table 3) that helps to understand step by step the evolution of the contemporary tourism sector in Cuba.

Table 3 Evolution of tourism in Cuba

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Pre 1959 | Tourism was the country's second largest exportable commodity; 350,000 tourists in 1958 accounted for 30% of all visitors to the Caribbean. |

| 1960-1975 | Tourism was discouraged as a vehicle for the economy and virtually disappeared after the 1962 economic embargo imposed by the United States. |

| Intur (National Tourism Institute) was created to develop tourism policy and collect data. In 1978, 69,500 visitors arrived, an increase of 700% over 1974. | |

| 1982 | Decree Law No. 50 authorizing foreign investment through joint ventures is signed. |

| 1987 | Cubanacan emerges as the first tourism company formed to involve foreign capital in tourism |

| May 1990 | The first joint venture hotel opens in Varadero; Cubanacan/Sol Melia with a Spanish investment of US$87 million (the second and third hotels opened in 1991 and 1994, totaling about 1400 rooms). |

| December 1990 | The first contract for hotel management is signed with the German LTI Hotels (three more contracts followed in 1993). |

| January 1992 | Jamaica's Superclubs becomes first Caribbean hotel company to operate in Cuba |

| July 1992 | The Cuban constitution is amended and foreign investment is protected, business ownership by economic associations is recognized and the concept of property is modified. |

| July-August 1993 | Decree-Law 140 legalizes the dollar and opens up self-employment in certain sectors |

| 1993-1994 | Investment promotion and protection agreements were signed with the governments of Italy, Spain, France, Russia, Colombia and the United Kingdom. Canadian hotel lines begin operating several hotel properties in Canada |

| April-June 1994 | The government is restructured and the Ministry of Tourism (Mintur) is created, Intur specialists are broken down into the newly created tourism services companies: Gran Caribe, Horizontes, Isla Azul, Puerto Sol (marinas), Transtur (transportation), Abatur (supplies), Publicitur (advertising) and Caracol (purchases). Tourism revenues increased from US$20 million in 1988 to US$251 million in 1994. |

Source: Simon (1995)

Cuba went from being the great tourist center of the Caribbean to not receiving tourists in a matter of decades, a time that was well used by the regional competition to position and consolidate its position in the tourist market. With the change of policy in the 1980s, Cuba hopes to reverse the situation by opening the doors to foreign investment for the first time since the triumph of the Revolution, using the tourism sector as a pioneer in the application of this policy.

In the 1990s, for the Caribbean, the nine billion dollars from the tourism sector brought in six times the income of all traditional agricultural exports. By contrast, Cuba was unique in its dependence on sugar. In 1990, more than 75% of Cuba's exports came from sugar, while non-traditional goods (mainly citrus, fish and medical products) accounted for only 13% (Simon, 1995).

Cuba attracted about 620,000 visitors in 1994, which puts it on par with Aruba or the U.S. Virgin Islands, but is still a fraction of the capacity of the 1950s, when it was the regional tourism powerhouse, taking 20% to 30% of Caribbean tourist traffic (Simon, 1995). In 1994, Cuba attracted only 4% of Caribbean tourist traffic. To begin to be competitive and attract tourists, Cuba based its strategy on being cheap, the costs of a tourist package in other Caribbean countries were double or sometimes triple that of Cuba.

But while foreign investment has performed positively, of concern are the operational difficulties arising from infrastructure deficiencies and supply shortages, to such an extent that Simon (1995) has since advised that, to recover its full potential, Cuba must greatly increase not only hotel partnerships, but also investment in all underlying sectors.

The new millennium has brought nothing but growth in the T&T sector in Cuba, Cuban GDP increased from $30.69 billion in 2002 to $114.1 billion in 2010 and 72.9% of it was generated with the service sector, despite the fact that tourism in Cuba has developed under the conditions of the economic embargo, imposed by the United States that restricts Cuba's international trade capacity and makes it difficult for U.S. tourists to travel to the island (Hingtgen et al., 2015).

A sample of this steady growth can be seen in figure 3, which shows, according to data taken from Séraphin (2018), the number of visitors by country for all those in the insular Caribbean from 2003 to 2014.

It is clear that the days of the 1990s, when Cuba received a small fraction of tourists and was comparable to Aruba or the Virgin Islands, are long gone. In the last decade, growth has been remarkable, although it remains to look at the tourism management of the Dominican Republic, which has been leading the list for years. It is therefore hard to understand the reasons why a country like Cuba, which clearly stands out in tourist arrivals, has no presence in the WEF ranking.

Despite relative success, several problems persist in tourism development, including low tourist return rates, reliance on low-cost package tours, competition in the Caribbean, lack of diverse tourism products, and limited investment in the sector. A sample of this is provided by Hingtgen et al. (2015) who note that despite the increase in visitation, average expenditures have decreased from US$1310 to US$876 per tourist, since 1995.

The concept of tourism has evolved over the years, as has the concept of tourism competitiveness, but although the former has a formally recognized concept, the latter is still the subject of debate and study. Over the years, several models have been created to measure tourism competitiveness, all of which have been criticized and none has managed to position itself as dominant or preferred by researchers.

The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index, although widely criticized in the literature, is the benchmark of current tourism competitiveness, reaching this point because of its comprehensiveness in terms of the number of destinations and the heterogeneity of indicators it considers. Several Central American and Caribbean countries, including Cuba, have been inexplicably absent from the World Economic Forum reports, thus limiting the perspective that future investors may have on tourism management in the region.

Tourism in Cuba, although it does not have the tourist attraction rates of the mid-twentieth century, has had a vertiginous growth in the region and has positioned itself as a key sector in the national economy.

Referencias bibliográficas

Andrades, L., & Dimanche, F. (2017). Destination competitiveness and tourism development in Russia: Issues and challenges. Tourism Management, 62, 360-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.05.008 [ Links ]

Briceno Garmendia, C., Bofinger, H., Cubas, D., & Millan Placci, M. F. (2015). Connectivity for Caribbean countries: An initial assessment World Bank Policy (N.o 7169; Research Working Paper). World Bank Group. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/21397 [ Links ]

Calderwood, L. U., & Soshkin, M. (2019). The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019/ [ Links ]

Croes, R. (2016). Connecting tourism development with small island destinations and with the well-being of the island residents. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.01.007 [ Links ]

Croes, R., & Kubickova, M. (2013). From potential to ability to compete: Towards a performance-based tourism competitiveness index. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(3), 146-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.07.002 [ Links ]

Crouch, G. I., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1999). Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 137-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3 [ Links ]

de la Peña, M. R., Núñez Serrano, J. A., Turrión, J., & Velázquez, F. J. (2019). A New Tool for the Analysis of the International Competitiveness of Tourist Destinations Based on Performance. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 207-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517746012 [ Links ]

Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667962 [ Links ]

Gómez Vega, M., & Picazo Tadeo, A. J. (2019). Ranking world tourist destinations with a composite indicator of competitiveness: To weigh or not to weigh? Tourism Management, 72, 281-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.006 [ Links ]

Gooroochurn, N., & Sugiyarto, G. (2005). Competitiveness Indicators in the Travel and Tourism Industry. Tourism Economics, 11(1), 25-43. https://doi.org/10.5367/0000000053297130 [ Links ]

Hingtgen, N., Kline, C., Fernandes, L., & McGehee, N. G. (2015). Cuba in transition: Tourism industry perceptions of entrepreneurial change. Tourism Management, 50, 184-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.033 [ Links ]

Hong, W.-C. (2009). Global competitiveness measurement for the tourism sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 12(2), 105-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802596359 [ Links ]

Kim, C. W., Choi, K. T., Moore, S., Dwyer, L., Faulkner, B., Mellor, R., & Livaic, Z. (2001). Destination Competitiveness: Development of a Model with Application to Australia and the Republic of Korea [Unpublished report]. Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Australia; the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Korea; the Korean Tourism Research Institute; the CRC for Sustainable Tourism, Australia; and the Australia-Korea Foundation. http://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=2001&author=+Kim%2C+C.W.author=+K.T.+Choiauthor=+Stewart+Moore%2C+Larryauthor=+Dwyerauthor=+Bill+Faulknerauthor=+Robert+Mellorauthor=+Zelko+Livaic&title=%22Destination+Competitiveness%3A+Development+of+a+Model+with+A pplication+to+Australia+and+the+Republic+of+Korea.%22 [ Links ]

McLeod, M., Lewis, E. H., & Spencer, A. (2017). Re-inventing, revolutionizing and transforming Caribbean tourism: Multi-country regional institutions and a research agenda. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 6(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.08.009 [ Links ]

Parra López, E., & Oreja Rodríguez, J. R. (2014). Evaluation of the competiveness of tourist zones of an island destination: An application of a Many-Facet Rasch Model (MFRM). Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 3(2), 114-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.12.007 [ Links ]

Pulido Fernández, J. I., & Rodríguez Díaz, B. (2016). Reinterpreting the World Economic Forum's global tourism competitiveness index. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 131-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2016.08.001 [ Links ]

Salinas Fernández, J. A., Serdeira Azevedo, P., Martín Martín, J. M., & Rodríguez Martín, J. A. (2020). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100582 [ Links ]

Séraphin, H., Gowreesunkar, V., Roselé-Chim, P., Duplan, Y. J. J., & Korstanje, M. (2018). Tourism planning and innovation: The Caribbean under the spotlight. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 384-388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.03.004 [ Links ]

Simon, F. L. (1995). Tourism development in transition economies: The Cuba case. The Columbia Journal of World Business, 30(1), 26-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5428(95)90033-0 [ Links ]

Received: September 29, 2020; Accepted: April 03, 2021

texto en

texto en