Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3469

Rev cubana ciencias forestales vol.9 no.3 Pinar del Río sept.-dic. 2021 Epub 05-Sep-2021

Original article

Characterization of melliferous species in the tropical dry forest oriented to their conservation

1Universidad Estatal del Sur de Manabí. Ecuador.

In the Quimis area of the Jipijapa Canton, an investigation was carried out related to the characterization of plant species that provide sustenance to bees in the production of honey that is used by local residents involved in the Aroma y Miel Association, among other uses, to market it. The objective of this study was based on characterizing the melliferous species of the tropical dry forest oriented to its conservation. Seven active apiaries distributed within the enclosure were selected, where four weekly samplings were made, with a total of 28 transects of 20 m x 50 m, taking as a starting point the apiaries to identify and count the number of species of apicultural use. A total of 31 species, 1,527 individuals, belonging to 16 families were determined. The botanical family with the highest abundance was Fabaceae with 290 individuals, and the most abundant species were Ceiba trichistandra (A. Gray) Bakh and Prosopis pallida (Willd.) Kunth, due to the greater beekeeping use and commercialization. The most frequent biological types were trees, followed by shrubs, herbaceous and lianas, respectively. The months of greatest flowering are from March to the beginning of October.

Palabras clave: Trees; Dry forest; Bee flora; Flowers.

INTRODUCTION

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2018), forests are home to more than three quarters of the world's terrestrial biodiversity and constitute an invaluable resource for the socio-economic development of hundreds of millions of people, mainly in rural areas. Among the main causes of forest loss are conversion to other land uses, mostly agriculture, deforestation, degradation and illegal logging practices.

Additionally, the recovery of forested areas, the reduction of logging and proper forest management have become priority activities to restore forests, the biodiversity they harbor and the environmental services they provide, as a strategy to cope with the effects of climate change (Miranda 2019).

Ecuador is a country rich in natural resources, with a climatic and biological diversity such as tropical and Andean forests (Vivanco, Rosillo and Macias, 2020). Beekeeping enterprises at the level of the country and the province of Manabi, are generally at a medium level with techniques oriented for sustainable management in order to obtain a good production (Guallpa, Guilcapi and Espinoza, 2019).

Bee flora or melliferous flora is known as the set of plant species in a region that produce substances or elements that bees collect for their benefit, generally nectar and pollen (Tejeda et al., 2019).

Other authors such as May and Rodríguez (2012), state that, in order to know possible conservation and restoration needs of ecosystems and to be able to adapt apiary management to changes in natural potential, it is important to have a good knowledge of the plants whose flowers the bees use to obtain honey and pollen, in their flowering seasons, and of the landscape components in which they are present. Such knowledge can also be used to assess the potential for producing honeys of a particular floral origin, which is important for marketing in international markets.

According to the Agencia Ecuatoriana Aseguramiento de la Calidad del Agro [AGROCALIDAD] (2017), Ecuadorian beekeeping is distributed in 902 beekeeping farms, of which 63 % are located in the highlands, 27 % in the coast, and 4 % in the Amazon. The land registry operation registered 12,188 hives, distributed with 46 % in two-story hives, 27 % in one-story hives, and 14 % in three-story hives.

The present investigation has been elaborated in the framework of the projects, "Components of the biological diversity used by the families of Manabí in the natural and traditional medicine", by the majoring on forest engineering, and "Biodiversity and Tourism in the coastal region of Ecuador", of the majoring on tourism, financed by the State University of the South of Manabí and has as objective to characterize the melliferous species that are in the Quimis enclosure, canton Jipijapa, oriented to its conservation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location of the area

The Quimis area belongs to the Jipijapa canton, it is located to the south of the Province of Manabí, it limits to the North with the parroquia La Pila; to the South with the Sancán community; to the East with the Cerrito la Asunción area and to the West, with the Membrillal parroquia.

Methodology

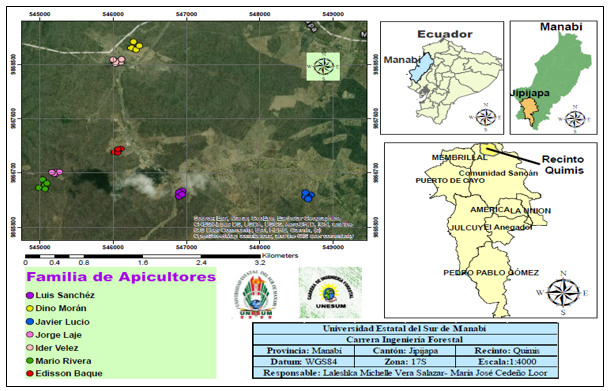

To characterize the melliferous species found in the Quimis enclosure, seven apiaries located in areas of the tropical dry forest described by the Ministry of Environment (MAE 2013) were investigated (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. - Location of the transects carried out in the area of influence of the seven selected active apiaries in the tropical dry forest of the Quimis area

The collected species were grouped by families, analyzing aspects of each taxa such as biological type, texture, and leaf size; then the chorological types were classified according to Borhidi (1996); the biological types of Raunkiaer (1905) determined according to the key of Ellenberg and Mueller-Dombois (1966, Ellenberg and Mueller-Dombois 1967); as well as the morphological characteristics and texture of the leaves (Valdés and Paneque 2008; Aguirre 2012).

As a reference to the classification of pollen and nectar obtained from the species found in the study, the criteria of Insuasty, Martinez and Jurado (2016) were taken into account.

In order to know the threat status of the melliferous species found in the Quimis area the Red List of the flora of Ecuador (International Union for Conservation of Nature) was reviewed (IUCN 2020). In the identification and taxonomic classification of the bee flora, the criteria of Insuasty, Martínez, and Jurado (2016) were taken into account.

The nomenclature of the melliferous species cited in the Quimis area was determined by reviewing the Tropics database of the Botanical Information System at the Missouri Botanical Garden, and the Catalogue of Life (Roskov et al., 2019), as for the Quimis area (Tropics 2020) and the Catalogue of Life (Roskov et al., 2019), while common names were provided by local guides (Jiménez 2012); (Jiménez, 2012); (Jiménez, Pionce, Sotolongo, & Ramos, 2016). On the other hand, the categories of cultivated, wild, endemic or introduced flora species were determined by reviewing the Red Book of the Flora of Ecuador (León et al., 2011) and the Encyclopedia of Useful Plants of Ecuador (De la Torre et al., 2008).

To carry out the transects, the methodology described by Aguilar et al., (2019) was used, in which, after selecting the active apiaries, four weekly samples were taken per apiary using transects of 20 x 50 m, thus the apiaries were taken as a starting point to identify and count the number of beekeeping species. During the tours and visits to the site, an invitation was received to attend a honey harvest in the apiary of Mr. Mario Rivera.

Data analysis

Shannon's index and the reciprocal of Simpson's index were calculated, with the objective of determining the species with the highest diversity in the forest that supports the life of the studied apiaries; according to what was reported by Jiménez et al. (2021), beekeepers have knowledge about the existing vegetation in the Quimis area, however, they do not know the totality of the melliferous species that exist around their apiaries and at the same time it was confirmed that Apis mellifera bees obtain food from several species which were not mentioned by the interviewees in that study.

RESULTS

Characterization of melliferous species found in the Quimis area, Jipijapa canton

A total of 31 species were inventoried distributed in the seven apiaries established in Quimis (Table 1) with a total of 1527 individuals.

Table 1. - Species identified in the Tropical Dry Forest of the Quimis site

| Scientific name | Families |

|---|---|

| Prosopis pallida (Willd.) Kunth | Fabaceae |

| Bonellia sprucei (Mez) B. Ståhl & Källersjö | Primulaceae |

| Caesalpinia paipai Ruiz & Pav. | Fabaceae |

| Ceiba trischistandra (A. Gray) Bakh. | Malvaceae |

| Trema micrantha (L.) Bl. | Cannabaceae |

| Croton rivinifolius Kunth | Euphorbiaceae |

| Acnitus arborencens (L.) Schltdl. | Solanaceae |

| Pithecellobium arboreum (L.) Urb. | Fabaceae |

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus (Benth.) Hauenschild. | Rhamnaceae |

| Convolvulus arvensis L. | Convolvulaceae |

| Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth | Convolvulaceae |

| Xenostegia medium(L.) D. F. Austin & G. W. Staples | Convolvulaceae |

| Vachellia macracantha (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) Seigler & Ebinger | Fabaceae |

| Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | Malvaceae |

| Eriotheca ruizii (K. Schum.) A. Robyns | Malvaceae |

| Leucaena trichodes (Jacq.) Benth. | Fabaceae |

| Coccoloba ruiziana Lindau | Polygonaceae |

| Mimosa acantholoba (Willd.) Poir. | Fabaceae |

| Cordia lutea Lam. | Ehretiaceae |

| Muntingia calabura L. | Muntingiaceae |

| Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana & Planch. | Burseraceae |

| Guapira floribunda (Hook. fil.) Lundell. | Nyctaginaceae |

| Erythrina velutina Willd. | Fabaceae |

| Vallesia glabra (Cav.) Link | Apocynaceae |

| Jatropha curcas L. | Euphorbiaceae |

| Pithecellobium excelsum (Kunth) Mart. | Fabaceae |

| Cynophalla flexuosa (L.) J. Presl | Capparaceae |

| Capparicordis crotonoides (Kunth) Iltis & Cornejo | Capparaceae |

| Geoffroea spinosa Jacq. | Fabaceae |

| Pisonia aculeata L. | Nyctaginaceae |

| Colicodendron scabridum (Kunth) Hutchinson | Capparaceae |

Among the most represented are the Fabaceae family with nine species, followed by the families Malvaceae, Capparaceae, Convolvulaceae with three species each one.

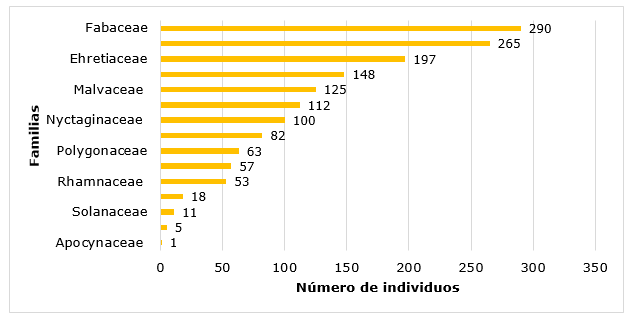

In Figure 2, the results of the abundance by families are presented, reaching the highest value Fabaceae, with 290 individuals, while the family Apocynaceae has only one individual (Figure 2).

Conservation status according to IUCN

As mentioned in Table 2, the Red List Category, for the most part, the species found in the Tropical Dry Forest of the Quimis area are in a conservation status of least concern (LC) or species with insufficient data (DD). On the other hand, the species Pithecellobium arboreum is the only species in the fourth category called "Vulnerable (VU), likewise Croton rivinifolius is the only species that is "Endangered (EN)" (Table 2).

Table 2. - Conservation status of melliferous species of the tropical dry forest in the Quimis área

| IUCN Category | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific name | DD | LC | NT | VU | EN | CR | EW | EX |

| Mimosa acantholoba | X | |||||||

| Pythecellobium arboreum | X | |||||||

| Caesalpinia paipai | X | |||||||

| Pithecellobium excelsum | X | |||||||

| Geoffroea spinosa | X | |||||||

| Erythrina velutina | ||||||||

| Prosopis pallida | ||||||||

| Vachellia macracantha | ||||||||

| Leucaena trichodes | ||||||||

| Jatropha curcas | X | |||||||

| Croton rivinifolius | X | |||||||

| Pisonia aculeata | X | |||||||

| Guapira floribunda | X | |||||||

| Bursera graveolens | X | |||||||

| Muntingia calabura | ||||||||

| Trema micrantha | ||||||||

| Ceiba trichistandra | X | |||||||

| Eriotheca ruizii | ||||||||

| Guazuma ulmifolia | X | |||||||

| Cordia lutea | X | |||||||

| Xenostegia médium | ||||||||

| Convolvulus arvensis | ||||||||

| Ipomoea purpurea | ||||||||

| Acnitus arborencens | ||||||||

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus | ||||||||

| Coccoloba ruiziana | ||||||||

| Vallesia glabra | X | |||||||

| Cynophalla flexuosa | X | |||||||

| Colicodendron scabridum | X | |||||||

| Capparicordis crotonoides | ||||||||

| Bonellia sprucei | ||||||||

Note: DD= data deficient; LC= Least Concern; NT= Near Threatened; VU= Vulnerable; EN= Endangered; CR= Critically Endangered; EW=Extinct in the Wild; EX=Extinct from the Wild.

Chorological classification

The results of the chorology are presented in (Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 3. - Biological types and forest types of the melliferous species inventoried in the Quimis área

| Scientific name | Biological type | Forest type |

|---|---|---|

| Mimosa acantholoba | Mcp | Bsp |

| Pithecellobium arboreum | Msp | Bsp |

| Caesalpinia paipai | McMsp | Bsp |

| Pithecellobium excelsum | M-Mcp | Bsp |

| Geoffroea spinosa | Msp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Erythrina velutina | Msp | Bsp |

| Prosopis pallida | McMsp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Vachellia macracantha | McMsp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Leucaena trichodes | M-Mcp | Bsp |

| Jatropha curcas | M-Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Croton rivinifolius | Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Pisonia aculeata | Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Guapira floribunda | Msp | Bsp |

| Bursera graveolens | Msp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Eriotheca ruizii | Msp | Bsp |

| Muntingia calabura | Msp | Bsp/Bsa/Bsap |

| Trema micrantha | Mcp | Bsp/Bsa/BsvtbC |

| Ceiba trichistandra | Mgp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | McMsp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Cordia lutea | Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Xenostegia médium | P | Bsp/Bsa |

| Convolvulus arvensis | H | Bsp/Bsa |

| Ipomoea purpurea | H | Bsp/Bsa |

| Acnitus arborencens | Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus | Msp | Bsp |

| Coccoloba ruiziana | Mcp | Bsp |

| Vallesia glabra | M-Mcp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Cynophalla flexuosa | McMsp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Colicodendron scabridum | Msp | Bsp/Bsa |

| Capparicordis crotonoides | M-Mcp | Bsp |

| Bonellia sprucei | McMsp | Bsp |

Legend: biological types: microphanerophytes (Mcp)= small between 5- 10 m; mesophanerophytes (Msp)= trees 15- 30 m; micromesophanerophytes (McMsp)= small to medium-sized trees 8- 15 m; micronano-panerophytes (M-Mcp)= woody plants between 2- 5 m; hemicryptophytes (H)= perennial herbs with buds on the soil surface; phanerophytes (P)= plants with woody stems, shrubs or herbs with stems over 50 cmtall; mega-phyanerophytes (Mgp)= large trees, over 30 m; dry forest type: Bsp= pluvio-seasonal dry forest; Bsa= Andean dry forest; Bsap= piedmont Andean evergreen forest; BsvtbC= lowland evergreen forest Chocó.

Table 4. - Characteristics of the leaves of the species of the Tropical Dry Forest of the Quimis site

| Scientific name | Blade type | Composite sheet type | Sheet size | Leaf edge | Leaf shape | Leaf texture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mimosa acantholoba | Hc | Cbi | Nan | Be | Fli | Car |

| Pithecellobium arboreum | Hc | Cbi | Lep | Be | Fli | Car |

| Caesalpinia paipai | Hc | Cbi | Nan | Be | Fova | Mem |

| Pithecellobium excelsum | Hc | Cbi | Mic | Be | Fova | Car |

| Geoffroea spinosa | Hc | Cbi | Lep | Be | Fli | Car |

| Erythrina velutina | Hc | Ctri | Not | Bl | Fe | Mem |

| Prosopis pallida | Hc | Cbi | Nan | Be | Fli | Mem |

| Vachellia macracantha | Hc | Cbi | Nan | Be | Fob | Mem |

| Leucaena trichodes | Hc | Cimp | Mic | Be | Fl | Car |

| Jatropha curcas | Hs | Not | Bl | Ft | Mem | |

| Croton rivinifolius | Hs | Ctri | Not | Be | Fl | Car |

| Pisonia aculeata | Hs | Mic | Be | Fl | Mem | |

| Guapira floribunda | Hs | Not | Be | Fe | Mem | |

| Bursera graveolens | Hc | Cimp | Not | Bd | Fc | Mem |

| Eriotheca ruizii | Hs | Not | Bl | Fe | Mem | |

| Muntingia calabura | Hs | Not | Bd | Fl | Suc | |

| Trema micrantha | Hs | Not | Be | Fe | Mem | |

| Ceiba trichistandra | Hc | Cpa | Mes | Be | Fe | Car |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | Hs | Not | Bd | Fl | Mem | |

| Cordia lutea | Hs | Not | Bd | Fe | Cor | |

| Xenostegia médium | Hs | Not | Bl | Fc | Mem | |

| Convolvulus arvensis | Hs | Not | Bl | Ft | Suc | |

| Ipomoea purpurea | Hs | Not | Bl | Ft | Mem | |

| Acnitus arborencens | Hs | Not | Be | Fe | Suc | |

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus | Hs | Not | Bd | Fob | Car | |

| Coccoloba ruiziana | Hs | Not | Be | Fov | Car | |

| Vallesia glabra | Hs | Mic | Be | Fl | Suc | |

| Cynophalla flexuosa | Hc | Cimp | Mic | Be | Fa | Cor |

| Capparicordis crotonoides | Hs | Not | Be | Fl | Cor | |

| Colicodendron scabridum | Hs | Not | Be | Fz | Cor | |

| Bonellia sprucei | Hc | Cimp | Mes | Be | Fo | Cor |

Legend: leaf type: Hs= simple leaf; Hc= compound leaf; compound leaf type: Cbi= compound bifolate leaves; Cimp= compound imparipinnate leaves; Ctri= compound trifolate leaves; Cpa= compound palmate leaves; leaf size: nanophyllous (Nan)= area up to 0.25 cm2 and length 0.5 - 1cm; notophyllous (Not)= area up to 12.5 cm2 and length 6-23cm; microphyllous (Mic)= area 1.75 cm2 and length 1- 6 cm; leptophyllous. (Lep)= small leaves with an area of less than 0.25 cm2 and length of 1-5 mm; mesophilic (Mes)= area up to 2.5 cm2 and length of 13- 20 cmapophyllous. (Af)= leafless; leaf margin: Be= entire margin; Bl= lobed margin; Bd= serrated margin; leaf shape: Fli= linear shape; Fe= elliptic shape; Fl= lanceolate shape; Fova= ovate shape; Fob= oblong shape; Ft= triangular shape; Fc= cordate shape; Fo= oblanceolate shape; Fz= tendril shape; Fov= ovate shape; Fa= acicular shape; leaf texture: cartaceous (Car)= like cardboard or paper; membranous (Mem)= extremely soft in texture; coriaceous (Cor)= leather-like hard; succulent (Suc)= fleshy.

Table 5. - Characteristics of the trunks of the species of the Tropical Dry Forest of the Quimis site

| Scientific name | Stem type | Texture of the crust |

|---|---|---|

| Mimosa acantholoba | Tl | Tr |

| Pithecellobium arboretum | Tl | Tr |

| Caesalpinia paipai | Tl | Tli |

| Pithecellobium excelsum | Tl | Tr |

| Geoffroea spinosa | Tl | Tr |

| Erythrina velutina | Tl | Tli |

| Prosopis pallida | Tl | Tr |

| Vachellia macracantha | Tl | Tr |

| Leucaena trichodes | Tl | Tli |

| Jatropha curcas | Tl | Tli |

| Croton rivinifolius | Tl | Tli |

| Pisonia aculeata | Tl | Tli |

| Guapira floribunda | Tl | Tli |

| Bursera graveolens | Tl | Tli |

| Eriotheca ruizii | Tl | Tli |

| Muntingia calabura | Tl | Tli |

| Trema micrantha | Tl | Tr |

| Ceiba trichistandra | Tl | Tli |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | Tl | Tr |

| Cordia lutea | Tl | Tr |

| Xenostegia medium | Th | Tli |

| Convolvulus arvensis | Th | Tli |

| Ipomoea purpurea | Lia | Tli |

| Acnitus arborencens | Tl | Tli |

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus | Tl | Tli |

| Coccoloba ruiziana | Tl | Tli |

| Vallesia glabra | Tl | Tr |

| Cynophalla flexuosa | Tl | Tr |

| Capparicordis crotonoides | Tl | Tr |

| Colicodendron scabridum | Tl | Tr |

| Bonellia sprucei | Tl | Tr |

Legend: stem type: Tl=woody stem; Th=herbaceous stem; Lia= liana; stem texture: Tli=smooth stem; Tr= rough stem.

The results of melliferous species according to pollen supply, nectar supply or both (Table 6).

Table 6v - Distribution of melliferous species according to their contribution of pollen and nectar to bees in honey production

| Melliferous species | Pollen | Nectar | Pollen/Nectar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acnitus arborencens | X | ||

| Vachellia macracantha | X | ||

| Pithecellobium excelsum | X | ||

| Ceiba trichistandra | X | ||

| Guazuma ulmifolia | X | ||

| Capparicordis crotonoides | X | ||

| Colicodendron scabridum | X | ||

| Prosopis pallida | X | ||

| Eriotheca ruizii | X | ||

| Convolvulus arvensis | X | ||

| Bursera graveolens | |||

| Guapira floribunda | X | ||

| Erythrina velutina | X | ||

| Pithecellobium arboreum | X | ||

| Mutingia calabura | X | ||

| Xenostegia médium | X | ||

| Cordia lutea | X | ||

| Cynophalla flexuosa | X |

Table 7 shows the categories of flora species according to whether they are cultivated, native, endemic, introduced or wild (Table 7).

Table 7. - Plants categorized according to their management category

| Scientific name | C | N | E | I | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mimosa acantholoba | |||||

| Pithecellobium arboreum | X | ||||

| Caesalpinia paipai | X | ||||

| Pithecellobium excelsum | X | ||||

| Geoffroea spinosa | X | ||||

| Erythrina velutina | X | ||||

| Prosopis pallida | X | ||||

| Vachellia macracantha | X | ||||

| Leucaena trichodes | X | ||||

| Jatropha curcas | X | X | |||

| Croton rivinifolius | X | X | |||

| Pisonia aculeata | X | ||||

| Guapira floribunda | |||||

| Bursera graveolens | X | ||||

| Muntingia calabura | X | ||||

| Trema micrantha | X | ||||

| Ceiba trichistandra | X | ||||

| Eriotheca ruizii | X | ||||

| Guazuma ulmifolia | X | ||||

| Cordia lutea | X | ||||

| Xenostegia médium | X | X | |||

| Convolvulus arvensis | X | ||||

| Ipomoea purpurea | |||||

| Acnitus arborencens | |||||

| Sarcomphalus thyrsiflorus | X | ||||

| Coccoloba ruiziana | X | X | |||

| Vallesia glabra | X | ||||

| Cynophalla flexuosa | |||||

| Colicodendron scabridum | |||||

| Capparicordis crotonoides | |||||

| Bonellia sprucei | X |

Note: C (cultivated); S (wild); E (endemic); I (introduced); N (native).

As detailed in the table above, most of the species are native to the Tropical Dry Forest, on the other hand, the species Croton rivinifolius is endemic to the Quimis area.

Shannon and Simpson Index (D)

According to the results, the diversity of species according to the Shannon index is classified as a high diversity in the area of the Quimis area, evidenced by the result obtained H=4.2656. In this same sense, Cordia Lutea species stand out; while Pithecellobium arboreum and Vallesia glabra present low dominance in the study area.

The results of the reciprocal of Simpson's Dominance (λ) = 0.06 and Simpson's (1-λ) = 0.93 show a high expectation for a random selection of two or more individuals of the same species in the established research area.

DISCUSSION

According to the results of the diversity of species inventoried in the Quimis enclosure through sampling it was found that these results differ with those obtained by Aguilar et al., (2019), who reported 89 species, 39 families, and 2 394 individuals. Likewise, the results of the botanical species mentioned coincide with those reported by (MAE 2013).

On the other hand, the IUCN reported the species Croton rivinifolius as endangered (EN), i.e. it has a high risk of extinction in the wild, which agrees with the reports of Astudillo-Sánchez et al., (2019), while the species Pithecellobium arboreum is considered vulnerable (VU), being evaluated in 2020, as presented in the IUCN Red Book (IUCN 2020). In this sense, both species face a risk of extinction or population decline in the medium term.

The species Colicodendron scabridum and Bursera graveolens, according to the IUCN Red Book, are categorized as LC (least concern), i.e. they are not critically endangered. On the other hand, Carrillo (2015) does not agree with the threat status of those two species, as he considers them to be categorized as critically endangered (CR).

According to the chorological classification of each species mentioned in the Quimis area, which was carried out with the aim of obtaining data on the structural characteristics of individuals, ie: root, stem, leaves, fruits, it was found that this coincides with that reported in other studies, such as those of REDMIC (2019), which briefly ensure the concept of chorology as a study that occupies the area of distribution of organisms associated with the date of sampling or observation, in addition to introducing the species with the date of sampling in the locality indicated, other data of interest is incorporated, i.e., the depth, degree of uncertainty of the coordinates, reliability of the identification and location, author of the collection or observation, number of specimens and a field of notes where it can be commented on relevant information associated with the data. Other works with different results mention the elaboration and chorological classification from a single specimen (Salas and Déniz, 2019).

The polliniferous and nectariferous species observed in the Quimis area, that in effect there are about 23 species of plants visited by the bees and that not only focus on the most common such as; the Ceiba trichistandra and Prosopis pallida that are the most used by the beekeepers, if not that these travel around the other species that are in the forest; such as the rastrearas and the shrubs managing to obtain their own food.

On the other hand, Insuasty, Martínez and Jurado (2016), indicated that certain species can be used by Apis mellifera as alternative polliniferous resources, when there is a low availability of pollen contributing species around the apiaries, which coincides with this study.

Likewise, the species with the highest number of individuals was Cordia lutea, while Vallesia glabra presented the lowest number of individuals in relation to the data cited by Jiménez et al. (2017), who mentioned that these species have flowers useful for the production of pollen and honey due to their long flowering, aroma or chemical properties, among them: Acacia macracantha, Terminalia valverdeae, Tabebuia chrysantha, Cordia lutea and Eriotheca ruizii.

For continuity, it should be added that the Shannon index obtained with the data collected in Quimis reflects a high diversity of 4.26; differing from the analysis conducted by Muñoz, Erazo and Armijos (2014), in southwestern Ecuador who reported a value of 2.51 indicating a medium diversity. Similarly, Simpson's index showed a high dominance (S=0.93); similar to that reported by a study of the floristic composition and structure of the dry forests of the Province of Loja, Ecuador Aguirre et al., (2013), who reported a high dominance (S= 0.89).

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

AGUIRRE, Z. 2012. Especies forestales de los bosques secos del Ecuador. Guía dendrológica para su identificación y caracterización. Quito, Ecuador. [en línea] Disponible en: https://docplayer.es/10228905-Especies-forestales-de-los-bosques-secos-del-ecuador-especies-forestales-bosques-secos-de-los-del-ecuador-o-r-n-e.html [ Links ]

AGROCALIDAD. 2017. Introducción para la obtención del certificado sanitario de funcionamiento de explotación apícola. Proyecto MAGAD y AGROCALIDAD, Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganaderia, Acuacultura y Pesca, Coordinación general de sanidad animal, Quito. [en línea] Disponible en: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ecu167273anx.pdf [ Links ]

AGUILAR, Á. B., AKER, C., & PACHECO, S. A. 2019. Caracterización florística de las especies de aprovechamiento apícola en el complejo volcánico "Pilas el Hoyo". Revista Iberoamericana de Bioeconomia y Cambio Climático, [en línea] vol 5 no.5 1164-1197. DOI 10.5377/ribcc.v5i9.7952 Disponible en: https://redib.org/Record/oai_articulo2834168-caracterizaci%C3%B3n-flor%C3%ADstica-de-las-especies-de-aprovechamiento-ap%C3%ADcola-en-el-complejo-volc%C3%A1nico-%E2%80%9Cpilas-el-hoyo%E2%80%9D [ Links ]

AGUIRRE, Z., BETANCOURT, Y., GEADA, G., & JASEN, H. 2013. Composición Florística, estructura de los bosques secos y su gestión para el desarrollo de la provincia de Loja, Ecuador. Revista Avance, [en línea] vol 15 no.2, 144-155. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet /articulo?codigo=5350870 [ Links ]

ASTUDILLO, E., PÉREZ, J., TROCCOLI, L., & APONTE, H. 2019. Composición, estructura y diversidad vegetal de la reserva Ecológica Comunal Loma Alta, Santa Elena, Ecuador. Revista Mexicana de biodiversidad, [en línea] 90, 1-25. doi: Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2871 [ Links ]

BORHIDI, A. 1996. Phytogeography and vegetation. Ecology of Cuba. Budapest: Academia Kiodo. [en línea] Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272562956_Phytogeography_and_Vegetation_Ecology_of_Cuba [ Links ]

CARRILLO, K. 2015. Flora y vegetación del bosque seco de la comunidad campesina Cesar Vallejo de Palo blanco, Chulucanas-Piura. Piura: Consercio Naturaleza y Gestión Ambiental. [en línea]. Disponible en: https://docplayer.es/93755882-Flora-y-vegetacion-del-bosque-seco-de -palo-blanco-comunidad-campesina-cesar-vallejo-de-palo-blanco-chulucanas-piura.html [ Links ]

DE LA TORRE, L., NAVARRETE, H., MURIEL, P., MACÍA, M., & BALSLEV, H. 2008. Enciclopedia de las Plantas Útiles del Ecuador (Primera ed.). Edition: 1 Publisher: Herbario QCA de la Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador & Herbario AAU del Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad de Aarhus. [en línea] ISBN: 978-9978-77-135-8. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310828407_Enciclopedia_de_las_Plantas_Utiles_del_Ecuador [ Links ]

ELLENBERG, H., MUELLER-DOMBOIS, D., 1966. A key to Raunkiaer plant life forms with revised subdivisions. Ber Geob Inst ETH Stiftung Rübel, Zürich; [en línea] 37: 56-73. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267393597_A_Key_to_Raunkiaer_plant_life_forms_with_revised_subdivisions [ Links ]

ELLENBERG, H., & MUELLER-DOMBOIS, D. 1967. Tentative key to a physiognomic classification of plant formations of the earth, based on a discussion draft of the UNESCO working group on vegetation classification and mapping. Sine loco. [en línea] Disponible en: https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=bgi-002:1965:37::129 [ Links ]

GARDEN, M. B. (Ed.). 2020. Trópicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. Disponible en: https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/media/factpages/tropicos.aspx [ Links ]

GUALLPA, M. Á., GUILCAPI, E. D. & ESPINOZA, A. E. 2019. Flora apícola de la zona estepa espinosa Montano Bajo, en la Estación Experimental Tunshi, Riobamba, Ecuador. Revista Dominio de las Ciencias, [en línea] vol 5 no.2, 71-93. Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6989257 [ Links ]

INSUASTY, E., MARTÍNEZ, J., & JURADO, H. 2016. Identificación de flora y análisis nutricional de miel de abeja para la producción apícola. Revsita Biotecnología en el sector agropecuario y agroindustrial, [en línea] vol 14 no. 1, 37-44. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1692-35612016000100005 [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ, A. 2012. Contribución a la ecología del bosque semideciduo mesófilo en el sector oeste de la Reserva de la Biosfera "Sierra del Rosario. Tesis en opción al grado cientifico de Doctor en Ciencia Forestales, Universidad de Pinar del Río Hermanos Montes de Oca, Pinar del Rio. [en línea] Disponible en: https://rc.upr.edu.cu/handle/DICT/521 [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ, A., PIONCE, G. A., SOTOLONGO, R., & RAMOS, M. P. 2016. Perturbaciones humanas sobre la composición y estructura del bosque semideciduo mesófilo, reserva de la biósfera Sierra del Rosario, Cuba. Revista SATHIRI, [en línea] 10, 196-206. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332657758_Perturbaciones_humanas_sobre_la_composicion_y_estructura_del_bosque_semideciduo_mesofilo_reserva_de_la_biosfera_Sierra_del_Rosario_Cuba [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ, A., PINCAY, F. A., RAMOS, M. P., MERO, O. F., & CABRERA, C. A. 2017. Utilización de productos forestales no madereros por pobladores que conviven en el bosque seco tropical. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Forestales: CFORES, [en línea] vol 5 no. 3, 270-286. Disponible en: http://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/264/html [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ, A., CANTOS, C. G., CEDEÑO, M. J. & VERA, L. M. 2021. Caracterización de la producción apícola en un sistema cooperativo asociado al bosque seco tropical.UNESUM-Ciencias. Revista Científica Multidisciplinaria [en línea] ISSN 2602-8166, vol 5 no. 3, 47-60. Disponible en: http://revistas.unesum.edu.ec/index.php/unesumciencias/article/download/558/333 [ Links ]

LEÓN, S., VALENCIA, R., PITMAN, N., ENDARA, L., ULLOA, C., & NAVARRETE, H. 2011. Libro rojo de las plantas endémicas del Ecuador (Segunda ed.). Quito: Publicaciones del Herbario QCA, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. [en línea] Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318970039_Libro_Rojo_de_las_Plantas_Endemicas_del_Ecuador [ Links ]

MAY, T., & RODRÍGUEZ, S. 2012. Plantas de interés apícola en el paisaje: observación de campo y percepción de apicultores en República Dominicana. Revista Geográfica de América Central, [en línea] vol 1 no. 48, 133-162. Disponible en: https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/geografica/article/view/4002 [ Links ]

MINISTERIO DEL AMBIENTE DEL ECUADOR [MAE]. 2013. Sistema de Clasificación de los Ecosistemas del Ecuador Continental. Quito: Subsecretaría de Patrimonio Natural. [en línea] Disponible en: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/09/LEYENDA-ECOSISTEMAS_ECUADOR_2.pdf [ Links ]

MIRANDA, R. 2019. Restauración productiva de bosques en comunidades ubicadas en zonas de recuperación, uso especial y de amortiguamiento en tres áreas protegidas de Guatemala. Revista Mesoamericana de Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, [en línea] vol. 3no.6, 22-36. Disponible en: https://www.revistayuam.com/restauracion-productiva-de-bosques-en-comunidades-ubicadas-en-zonas-de-recuperacion-uso-especial-y-de-amortiguamiento-en-tres-areas-protegidas-de-guatemala/ [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, J., ERAZO, S., & ARMIJOS, D. 2014. Composición florística y estructura del bosque seco de la quinta experimental "El Chilco" en el suroccidente del Ecuador. Revista Cedamaz, [en línea] vol 4 no. 1, 53-61. Disponible en: https://revistas.unl.edu.ec/index.php/cedamaz/article/view/238/221 [ Links ]

ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA [FAO]. 2018. El estado de los bosques del mundo (SOFO). Roma, Italia: FAO. [en línea] Disponible en: http://www.fao.org/publications/card/es/c/I9535ES/ [ Links ]

RAUNKIAER, C. 1905. Types biologiques pour la géographie botanique. Videnskabernes Selskabs Oversigter [en línea] 1905; 347-438. Disponible en: http://publ.royalacademy.dk/backend/web/uploads/2019-09-04/AFL%203/O_1905_00_00_1905_4676/O_1905_15_00_1905_4672.pdf [ Links ]

REPOSITORIO DE DATOS MARINOS INTEGRADOS DE CANARIAS [REDMIC]. 2019. Repositorio de Datos Marinos Integrados de Canarias. Consulta: 17/09/2020, [en línea]. Disponible enDisponible en: https://redmicdev.wordpress.com/2019/04/24/corologia/ [ Links ]

ROSKOV, Y., OWER, G., NICOLSON, D., BAILLY, N., KIRK, P., DEWALT, R., PENEV, L. 2019. Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life. [en línea] Disponible en: http://www.catalogueoflife.org/annual-checklist/2019/ [ Links ]

SALAS, M., & DÉNIZ, E. A. 2019. Novedades y precisiones sobre la distribución de las especies del género ArbutusL. (Ericaceae) en Gran Canaria (Islas Canarias). Revista Botanica Complutensis [en línea] 43, 85-96. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/BOCM.65891 Disponible en: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7119123 [ Links ]

TEJEDA, G. E., GONZÁLEZ, S. J., MIRANDA, K. F., PALMERA, K. J., CARBONÓ, E. C., & SEPÚLVEDA, P. A. 2019. Flora con potencial apícola asociada a plantaciones orgánicas de palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis) en el departamento del Magdalena. Revista Palmas, [en línea] 40 4, 13-28. Disponible en: https://publicaciones.fedepalma.org/index.php/palmas/article/view/12906 [ Links ]

UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LA NATURALEZA [IUCN]. 2020. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [en línea] Consulta: 13/09/2020, Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.iucnredlist.org/es [ Links ]

VALDÉS, N. & PANEQUE, I. 2008. Aspectos corológicos y endemismo de la vegetación leñosa de ecosistemas de pinares naturales de alturas de pizarra. Avances, [en línea] vol 10 no.1, 1-7. Disponible en: http://www.ciget.pinar.cu/Revista/No.2008-1/art%EDculos/143%20Aspectos%20corologicos%20y%20Endemismo.pdf [ Links ]

VIVANCO, I., ROSILLO, W., & MACIAS, V. 2020. Comercialización apícola, tendencia del mercado en la Provincia del Guayas (Ecuador). Revista Espacios, [en línea] vol. 41 no. 21, 135-145. Disponible en: http://ww.revistaespacios.com/a20v41n21/a20v41n21p11.pdf [ Links ]

Received: April 07, 2021; Accepted: July 14, 2021

texto en

texto en