Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3469

Rev CFORES vol.12 no.1 Pinar del Río ene.-abr. 2024 Epub 02-Abr-2024

Original article

Spatial data integrated into numerical model for analysis meteorological and local climate in mountains of Cuba

1Instituto de Meteorología (INSMET). La Habana, Cuba.

2Centro de Desarrollo de la Montaña, Guantánamo, Cuba.

Local-scale weather and climate modeling in mountains has been relevant for the study of agroforestry ecosystems and their future evolution. The study aimed to integrate a set of high-resolution spatial data to the WRF numerical meteorological prediction and research model, suitable for meteorological and local climate analysis in the mountains of Cuba. In the study, priority spatial data were defined as those referring to the relief, the land mask as the ocean-soil interface, the type of cover and type of soil. The national or global high-resolution spatial databases of the best quality and most appropriate to the characteristics of the model were selected. The databases integrated into the WRF had spatial resolution between approximately 0.95 and 0.03 km in Ecuador. The increase and updating of spatial data strengthened the model's capacity for the analysis of the geographic factors that shape the local climate, promoting better performance in the mountains. The research results could contribute to meteorological and climate monitoring and forecasting at a local scale for the mountains of Cuba. Likewise, studies and risk management associated with forest fires, severe hydrometeorological events, climate variability, climate change, and other dangers related to the climate system that have affected Cuban agroforestry ecosystems would benefit.

Key words: numerical meteorological models; topoclimates; agroforestry ecosystems.

INTRODUCTION

The United Nations Declaration recognizes the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of mountain ecosystems and the services they provide, essential in achieving the goals of sustainable development. In Cuba, the implementation strategy of the National Economic and Social Development Plan for 2030 is carried out with the vision of confronting climate change. Correspondingly, the State Plan for Confronting Climate Change, "Task Life", is implemented, which specifies the need for analysis at a local scale. Agroforestry ecosystem services in Cuba are strongly linked to meteorological and climatic behavior at the local scale in the mountains, topoclimates (Molina-Pelegrín et al., 2021; Zamora Fernández, Azanza Ricardo and Bezanilla Morlot 2022). These services are susceptible to forest fires, severe hydrometeorological events, climate variability and change, among other dangers associated with the behavior of weather and climate (Zamora Fernández and Azanza Ricardo 2020; Hardy Casado et al., 2021; Pospehov et al., 2023). This link also implies impacts on the macroeconomic balances and the livelihoods of the mountain people.

In recent years, there have been advances in methodologies and services for meteorological and climate monitoring in the Greater Antilles (Delgado-Téllez and Peña-de la Cruz 2019; Centella-Artola et al. 2023; Peña-de la Cruz et al. 2023; Torres and Lorenzo 2023). Likewise, these advances are seen within the projections of the future climate at a spatial scale favorable to the evaluation of the impacts and adaptation strategies to climate change (Centella-Artola et al., 2020; Vichot-Llano et al., 2021). However, meteorological and climate monitoring and forecasting, analogous to the future projection of topoclimates, are still insufficient for the management of agroforestry ecosystem services in Cuba. The generality of the limitations of weather and climate monitoring and forecasting systems for mountains at a local scale are related to the poor performance of methodologies and tools in representing the physical and dynamic processes involved.

The numerical meteorological model for prediction and weather research, WRF (NCAR 2018) is one of the most used tools in weather and climate studies at regional and local scales (Afrizal and Surussavadee 2018; Wang et al., 2020). One of the reasons is attributed to the fact that the software and the frontier data for its use are available globally to the scientific community. Other reasons for its multiple applications are the flexibility of its architecture and its precision. The official WRF distribution ships with a preprocessing system (WPS for its acronym in English) and a set of geographical variables such as relief, location of land masses, hydrology, types and uses of land, as static boundary conditions. These global scale variables have spatial resolution of 10 minutes, 5 minutes and 30 arc-seconds, approximately 18.5 km, 9.25 km and 0.95 km respectively at the equator. This spatial resolution is timely for its fundamental purpose of mesoscale analysis. However, when WRF is used on larger scales, for example, applications associated with the analysis of topoclimates for agroforestry ecosystem services in mountains, the boundary conditions supplied with the software generally cannot resolve local phenomena. In these cases, the inclusion of data adjusted to the defined modeling scale is required.

This research aims to integrate a set of high-resolution spatial data available, such as WRF frontier databases, suitable for meteorological and local climate analysis in the mountains of Cuba.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

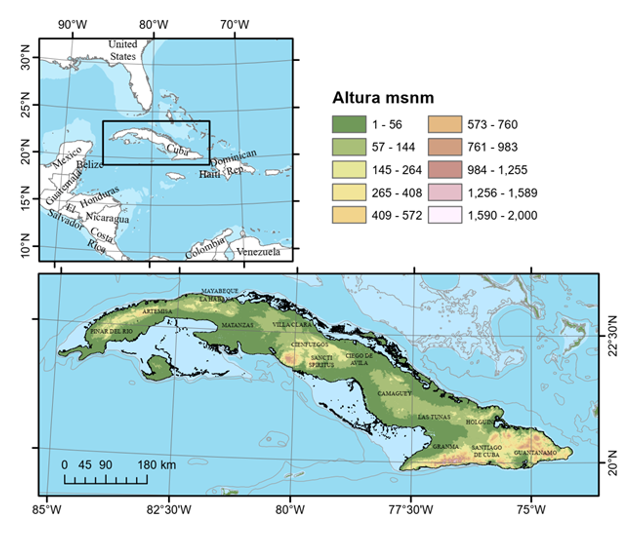

The research was carried out for the entire Cuban archipelago, located at 74º 08', 84º 58' West longitude and 23º 17', 19º 50' North latitude, a total area of 109,886 km² (Figure 1).

The WRF, mesoscale non-hydrostatic model, version v4.5 was used in the study. In the work, the relief, the land mask (ocean-soil interface), the type of cover and type of soil were defined as minimum static boundary data. These parameters are processed by the model preprocessing subsystem (WPS). National and global databases were used according to their availability and quality. Spatial databases with references in scientific journals were prioritized. In the case of national data not formally published, the official versions of the responsible organizations in the country were used. The high-resolution spatial databases of the best quality and most appropriate to the characteristics of the WRF were selected.

The research used the following national databases:

The National Cadastre of the Republic of Cuba, scale 1:10 000 of the Department of Physical Planning Projects, 2018.

The National Forest Cover Map, scale 1:100 000 of the State Forest Service, prepared by Estrada and collaborators in 2012.

The Genetic Map of the Soils of Cuba, scale 1:250 000, by Hernández Jiménez and collaborators, Academia de Ciencias, 1971.

The definition of the land mask aims to enable the WRF equations to differentiate the ocean surface from the land surface. The land mask was generated as a binary map (1 = land surface, 0 = sea surface) with 1 arc second of spatial resolution. To define the land area, the National Cadastre was used, which serves as the basis for the National Soil Balance. This initial mask was complemented with data from the digital surface model (DSM) to reflect the emerged lands not collected from the national territory, generally small keys. This land mask was applied to all the data generated in the study (relief, cover type and soil type) to guarantee homogeneity. The land mask and other areas covered by water, such as reservoirs and lagoons, are identified by the WPS from the coverage data.

Relief is one of the determining boundary parameters in the performance of numerical meteorological models. The ALOS WORLD 3D digital surface model (DSM) was used, generated by the Japanese PRISM mission, with a horizontal resolution of one arc-second, approximately 30 meters at the equator (Tadono et al., 2014). The selection of this model has the advantages of its global coverage and the representation of objects on the ground surface, such as vegetation and human modifications in the relief. Examples of the latter are earthquakes, tall buildings and roads. The limitations of this type of DSM are associated with possible errors in snowy areas or very steep and high slopes that are not of significant importance in the study area.

Due to the difference in scales of the national cadastre data with respect to other sources, a progressive adjustment process was carried out following the procedure described below:

Vector-raster conversion at 1 arc - second (approximately 30 m) spatial resolution.

Noise reduction by eliminating loose pixels and clusters smaller than approximately 1 km² in area.

Reclassification.

Data integration.

Application of sea/land mask.

In the research, the Capote and Berazaín (1984) classification of vegetation formations available as an attribute in the National Forest Map was used. The vegetation types were matched to the default cover classes in the WPS derived from the United States Geological Survey and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (USGS24+1 and MODIS20+1, respectively) classifications. The USGS24+1 classification takes into account 24 cover types and the aqueous surface. MODIS 20+1 data are divided into 20 coverage classes and aqueous surface. In both cases the aqueous surface refers to lakes and watercourses, as the area occupied by seas and oceans is one of the classes. This class is not part of the original classification, in which the area covered by water does not differentiate between lakes and ocean. It is a class added only for the modeling system, so it was defined in all cases.

In the case of soil, the Genetic Soil Map of Cuba, scale 1:250 000, was used. Approximate equivalences with the WRF soil data were obtained from the information of the soil texture field of the database to match both classifications.

This process of land and cover equivalence allowed the reuse of the parameters already encoded in the WRF without the need to modify the modeling source code, which would have required a complex and expensive process of recertification of the numerical model.

The update of the WPS metadata of the model was carried out for the entire Cuban archipelago, guaranteeing the physical coherence: thermodynamics and hydrodynamics, of the meteorological variables that characterize the agroforestry ecosystems throughout the country.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Relief

Two DSMs of the area of interest were generated, at scales of 30 and 1 arc-seconds in the binary format used by the WRF (GEOGRID.EXE). The boundary conditions attribute table (GEOGRID.TBL) was updated to use this data by default.

Type of coverage

When comparing the classification of Capote and Berazaín with the USGS24 and MODIS20, coincidences are observed in terms of general and edaphoclimatic characteristics of several classes. These coincidences made it possible to directly associate a part of the classifications. Tables 1 and 2 show examples of the correlations identified between the rankings. In los anexos1 and 2, the equivalences of the Capote and Berazain classifications with those of the USGS24 and MODIS20, respectively, used in the study are shown.

Table 1. - Examples of the equivalence of Capote and Berazain classifications with those of the USGS24

| No | Capote & Berazain | Code | USGS24 |

| 41 | Deciduous forest | eleven | Deciduous forest |

| 3. 4 | Typical cloud forest (1600-1900m) | 13 | Evergreen broadleaf forests |

| 32 | Microphyllous Semideciduous Forest | 8 | Charrascales |

| Four. Five | Holm oak | fifteen | Mixed forests |

| 44 | Swamp Thicket | 18 | forested wetland |

| 38 |

|

14 | Evergreen Coniferous Forests |

| 6 | Broadleaf Plantations | fifteen | Mixed forests |

| 26 | Low altitude rainforest | 13 | Evergreen broadleaf forests |

| 43 | Natural sheets SL | 10 | Bed sheets |

| 39 | Bare and semi-naked areas | 19 | Barren or sparse vegetation |

Table 2. - Examples of the equivalences of the Capote and Berazain classifications with those of MODIS20

| No | Capote & Berazain | Code M20 | MODIS20 |

| 41 | Deciduous forest | 4 | broadleaf deciduous forest |

| 3. 4 | Typical cloud forest (1600-1900m) | 2 | Evergreen broadleaf forest |

| 32 | Microphyllous Semideciduous Forest | 6 | closed charrascals |

| Four. Five | Holm oak | 5 | mixed forest |

| 44 | Swamp Thicket | eleven | Permanent wetlands |

| 38 |

|

1 | Evergreen coniferous forests |

| 6 | Broadleaf Plantations | 5 | Mixed forests |

| 26 | Low altitude rainforest | 2 | Evergreen broadleaf forest |

| 43 | Natural sheetsS. L | 9 | Bed sheets |

| 39 | Bare and semi-naked areas | 16 | Barren or sparsely vegetated |

The forest groupings of Capote and Berazaín, which due to their complexities did not have direct correspondences with MODIS24 and USGS20, were grouped taking into account their majority structure or specific composition in the objective classifications. These groupings are described below:

a) Five of the Capote and Berazaín groupings were grouped in the Deciduous Forests class: "Coastal and subcoastal microphyllous evergreen forests (dry forest)"; "Typical mesophilic semi-deciduous forest on acidic soil"; "Mesophyllous semi-deciduous forest with fluctuating humidity"; "Coastal semi-desert thorny shrubland" and "Undifferentiated shrublands, mostly secondary and marabuzales, bushes and grasses with shrublands, very degraded and sparse secondary forests."

b) In evergreen broadleaf forest they were grouped: "The typical evergreen swamp forest"; "Mogote vegetation complexes"; "Charrascales" such as "Thorny xeromorphic scrub on serpentinite (cuabal)"; "Coastal and subcoastal scrubland with an abundance of succulents (coastal bush)" and the "calciphobic microphyllous evergreen forest".

c) Additionally, the "Calciphobic microphyllous evergreen forests" and the "Terrace Vegetation Complex" were included in charrascales for both international coverage classifications.

The National Forest Map covers only forest areas, so the National Cadastre was used to complete the study area. In all cases, priority was assigned to the National Cadastre Map. Table 3 shows examples of the equivalences used between the type of use of the National Cadastre and those predetermined in the WRF. Annex 3 details the conversion used in the study.

Table 3. - Examples of the equivalences of types of use between the National Cadastre and those of the USGS24 and MODIS20

| Type of use national cadastre | IDUuse | USGS24 | MODIS20 |

| Support for agricultural production | 8420 | 1 | 13 |

| Urban settlements | 8010 | 1 | 13 |

| Rural settlements | 8020 | 1 | 13 |

| Freeways | 8110 | 1 | 13 |

| public railway | 8210 | 1 | 13 |

| Other transportation facilities | 8290 | 1 | 13 |

| Various crops | 1010 | 4 | 12 |

| Deforested | 5060 | 7 | 10 |

| Idle surface (livestock) | 4060 | 8 | 6 |

| Coffee | 2310 | 13 | 2 |

| Cocoa | 2410 | 13 | 2 |

| Natural forests | 5100 | 13 | 2 |

Two coverage databases were generated with the classes corresponding to USGS24+1 and MODIS20+1. Similar to the relief case, these cover type databases were transformed into the WRF executable binary format (GEOGRID.EXE). The result was updated to the corresponding attribute table. Two new tables were created available for modeling processes.

Soil type

In this case an equivalent raster resolution of 3 arc-seconds (approximately 90 m) was used. that appear in Table 4.

Table 4. - Equivalences used from the database of the Genetic Map of the Soils of Cuba with the soil categories of the WRF

| Texture | WRF soil class | Texture | WRF soil class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clay loam | 9 | Sand | 1 |

| Clay | 12 | Coalinitic clay | eleven |

| Clay-sandy loam- Sandy loam | 7 | sandy clay | 10 |

| Loam | 6 | loamy clay | 8 |

| Montmorillonitic clay | eleven | - | - |

The soil type database was transformed into the WRF executable binary format (GEOGRID.EXE). The result had the same treatment and generalization as those stated above. In this case the tables were updated using the same type of soil for the surface and the lower limit.

Post-processing and distribution of results

In total, 7 binary data packets were generated in a format compatible with the WRF WPS preprocessing system. This data is composed of a relief data package with 1 arc-second spatial resolution, two coverage packages with classes compatible with USGS24+1 at 1 and 30 arc-seconds, two coverage packages with classes compatible with MODIS20+1 at 1 and 30 arc-seconds, and two soil type data packages at 1 and 30 arc-seconds spatial resolution. Additionally, a specialized table was created for the configuration of the WRF preprocessing system (WPS_CUB.TAB) with the necessary parameters for its expeditious integration in the modeling. All of these data are integrated into the modeling system of the INSMET Center for Atmospheric Physics, and are available for use by the scientific community through contact with the authors.

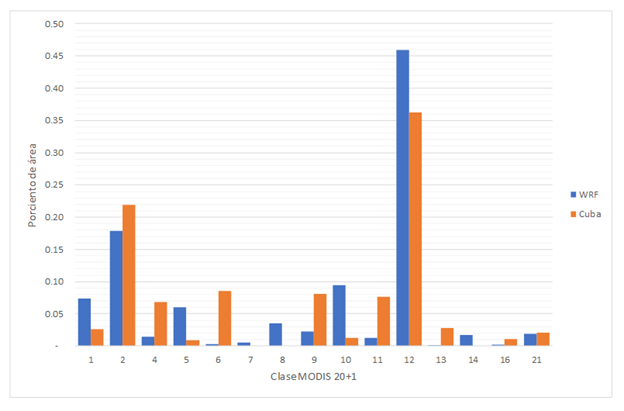

Contributions of the integration of high-resolution spatial databases to the WRF

When considering the contributions of the integration of high-resolution spatial databases to the WRF for the analysis of local climate in mountains of Cuba, the results achieved are consistent with a higher quality of static boundary conditions, as suggested in Varga and Breuer (2020) It is noteworthy that, as a result of the process carried out, significant changes were identified in the distribution of coverage classes between the data provided as default in the WRF and those compiled in this research. In general, the integrated data present a distribution more in line with what is expected for the Cuban archipelago. For example, in the case of MODIS 20+1 classes, there is an increase of more than 5 % in the areas of deciduous broadleaf forest, closed charrascal, savannas and permanent wetlands. This increase in area distribution was conditioned by the decrease in the area allocated to croplands and grasslands (8 and 10 %) among others. The better definition of populated areas should be noted, which increased from practically zero to 3 % of the national territory. Figure 2 shows the class distributions in greater detail. It is of special interest that class 21 (lakes and rivers) remains practically unchanged, which is consistent with the capacity of the MODIS instrument to detect areas covered with water very accurately (Chu et al. 2021) , a capacity that does not It necessarily extends to regions covered with tropical vegetation and anthropized. In the latter case, it is significant that global classification algorithms do not appropriately recognize populated areas in the study area, possibly extending to developing countries outside of major cities, which may be due to structural differences with the most developed regions.

Fig. 2. - Comparison between the area proportion of the original MODIS20+1 data (WRF) and that generated in this research (Cuba). 1: Evergreen coniferous forest, 2: Evergreen broadleaf forest, 4: Deciduous broadleaf forest, 5: Mixed forests, 6: Closed charrascal, 7: Open charrascal, 8: Savannas with trees, 9: Savannas, 10: Grasslands, 11: Permanent wetlands, 12: Cropland, 13: Urban and Built-up, 14: Mosaic of cropland and natural vegetation, 16: Barren or sparsely vegetated, 21: Lakes/rivers. The latter is the additional class. The ocean is not included

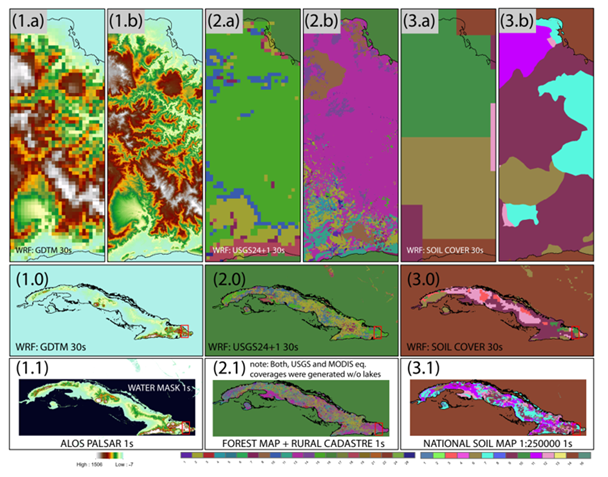

The results of the study, show a development in the definition of the distribution of cover and soil categories, with better identification of the land-sea interface. These changes are reflected in the increase in WRF performance at a local scale in mountain conditions identified by Peña-de la Cruz et al. to the. (2023). The first row of Figure 3, in cells b, presents examples of increasing the definition of the integrated data during the investigation. The second and third rows show the spatial resolution of the static boundary data in the WRF. In the second row, the default data in the model; in the third, the integrated high-resolution spatial data. In cell 1.1, the increase in the details of the geographical elements is evident, which corrects the definition of valleys, ravines and rivers in mountainous areas. Cell 2.1 allows us to observe the development between the surface databases, especially the better definition of the coastline and the variation in the distribution and type of cover. An example of the latter is notable in natural areas such as the mountain massifs and the Ciénaga de Zapata. In cell 3.1, a relatively common phenomenon can be seen in developing countries; the resolution of the supplied layer is even lower than 30 arcseconds, the resolution defined as default for this variable, soil type, in the WRF. This effect is common in spatial domains outside the most developed regions, where global data are scarcer and imprecise. In this case, to the increase in the spatial definition of the variable, greater class variability is added, with categories closer to the real conditions of the study area.

Fig.3. - Spatial databases in the WRF as static boundary conditions. The images in the 1st row: a, before and b, after the high-resolution spatial databases have been integrated. 2nd row: the default spatial databases in the model; 3rd row the integrated high-resolution spatial databases to the model

The improvements identified strengthen the capacity of WRF-based modeling to integrate the geographic factors that shape the local climate, with benefits especially in mountainous regions. Among the direct applications of the study, we can highlight the strengthening of the modeling and forecasting of meteorological conditions that influence the appearance and development of forest fires, as noted by Zamora Fernández et al. to the. (2020; 2022).

Likewise, the results obtained can contribute to increasing the spatial resolution and effectiveness de los estudiosof the present and future local climate in the mountains. Similarly, the results obtained in this research will benefit risk management studies associated with forest fires, severe hydrometeorological events, climate variability and climate change, and other hazards related to the climate system that have affected Cuban agroforestry ecosystems.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of a high-resolution spatial data set with the WRF model strengthens its capacity for the analysis of the geographic factors that shape local climate in the mountains. The integration of a high-resolution spatial data set with the WRF improves the model's ability for local-scale weather and climate monitoring and forecasting in the mountains of Cuba.

Thanks

The research that originated the results above mentioned received funds from the International Funds and Projects Management Office under the code PN211LH009-036 "Medium-term impacts of climate change on the topoclimates associated with coffee and cocoa in Cuba."

Anexo 1. (Table 5).

Table 5 - Equivalencias de las clasificaciones de Capote y Berazain con las del USGS 24

| No | Capote & Berazain | Código | USGS 24 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | Bosque Caducifolio | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 34 | Bosque nublado típico (1 600-1 900m) | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 35 | Bosque pluvial montano (800-1 600m) | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 8 | Bosque semideciduo mesófilo con humedad fluctuante | 13 | Bosque siempre verdes de hoja anchas |

| 1 | Bosque Semideciduo Mesófilo típico | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 16 | Bosque semideciduo mesófilo típico sobre suelo ácido | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 32 | Bosque Semideciduo Micrófilo | 8 | Charrascales |

| 42 | Bosque siempreverde de ciénaga bajo | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 7 | Bosque siempreverde de ciénaga típico | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 2 | Bosque siempreverde de mangles (manglar) | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas. |

| 17 | Bosque siempreverde mesófilo de baja altitud (menor de 400m) | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 27 | Bosque siempreverde mesófilo submontano (400-800m) | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 28 | Bosque siempreverde Micrófilo calcifobo | 8 | Charrascales |

| 4 | Bosque siempreverde Micrófilo costero y subcostero (monte seco) | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 18 | Bosques indiferenciados; mayoritariamente secundarios, seminaturales y ralos; plantaciones, arboledas, maniguas y matorrales | 13 | Bosque siempre verdes de hoja ancha |

| 30 | Charrascal Montano | 8 | Charrascales |

| 10 | Complejo de Vegetación de Mogote | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 36 | Complejo de Vegetación de Terrazas | 8 | Charrascales |

| 45 | Encinar | 15 | Bosques mixtos |

| 5 | Herbazal de Ciénaga | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 3 | Matorral costero y subcostero con abundancia de suculentas (manigua costera) | 8 | Charrascales |

| 44 | Matorral de Ciénaga | 18 | Humedal boscoso |

| 21 | Matorral Espinoso Semidesértico Costero | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 22 | Matorral xeromorfo espinoso sobre serpentinita (cuabal) | 8 | Charrascales |

| 29 | Matorral xeromorfo subespinoso sobre serpentinita (charrascal) | 8 | Charrascales |

| 19 | Matorrales indiferenciados, mayoritariamente secundarios y marabuzales, maniguas y pastos con matorrales, bosques secundarios muy degradados ralos | 11 | Bosque caducifolio |

| 40 | Matorrales sobre Arenita | 13 | charrascales |

| 35 | Monte Fresco | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 38 | Pinares de |

14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 9 | Pinares de |

14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 23 | Pinares de |

14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 33 | Pinares de |

14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 13 | Pinares de |

14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 12 | Plantaciones de Pino | 14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 14 | Plantaciones de Pino Jóvenes | 14 | Bosques siempre verdes de Coníferas |

| 6 | Plantaciones Latifolias | 15 | Bosques mixtos |

| 15 | Plantaciones Latifolias Jóvenes | 13 | Bosques siempre verdes de hojas anchas |

| 26 | Pluvisilva de baja altitud | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 31 | Pluvisilva Esclerofila Submontana sobre Mal Drenaje | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 24 | Pluvisilva Esclerofila Submontana sobre Serpentinita | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 25 | Pluvisilva Submontana sobre Comp. Metamórfico | 13 | Bosques siempreverdes de hojas anchas |

| 43 | Sabanas naturales S.L | 10 | Sabanas |

| 37 | Saladares | 19 | Estéril o escasa vegetación |

| 39 | Zonas desnudas y semidesnudas | 19 | Estéril o escasamente vegetado |

Anexo 2. (Table 6).

Table 6. - Equivalencias de las clasificaciones de Capote y Berazain con las del MODIS 20

| No | Capote & Berazain | Código | MODIS 20 |

| 41 | Bosque Caducifolio | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 34 | Bosque nublado típico (1 600-1 900m) | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 35 | Bosque pluvial montano (800-1 600m) | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 8 | Bosque semideciduo mesófilo con humedad fluctuante | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 1 | Bosque Semideciduo mesófilo típico | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 16 | Bosque semideciduo mesófilo típico sobre suelo ácido | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas | |

| 32 | Bosque Semideciduo Micrófilo | 6 | Charrascales cerrado |

| 42 | Bosque siempreverde de ciénaga bajo | 11 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 7 | Bosque siempreverde de ciénaga típico | 2 | Bosque siempre verde de hojas ancha |

| 2 | Bosque siempreverde de mangles (manglar) | 11 | Humedales permanentes |

| 17 | Bosque siempreverde mesófilo de baja altitud (menor de 400m) | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 27 | Bosque siempreverde mesófilo submontano (400-800m) | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 28 | Bosque siempreverde micrófilo calcifobo | 6 | Charrascales cerrados |

| 4 | Bosque siempreverde micrófilo costero y subcostero (monte seco) | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hoja anchas |

| 18 | Bosques indiferenciados; mayoritariamente secundarios, seminaturales y ralos; plantaciones, arboledas, maniguas y matorrales | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 30 | Charrascal Montano | 6 | Charrascales cerrados |

| 10 | Complejo de Vegetación de Mogote | 2 | Bosque siempre verde de hojas ancha |

| 36 | Complejo de Vegetación de Terrazas | 6 | Charrascal cerrado |

| 45 | Encinar | 5 | Bosque mixtos |

| 5 | Herbazal de Ciénaga | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 3 | Matorral costero y subcostero con abundancia de suculentas (manigua costera) | 6 | Charrascales cerrados |

| 44 | Matorral de Ciénaga | 11 | Humedales permanentes |

| 21 | Matorral Espinoso Semidesértico Costero | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 22 | Matorral xeromorfo espinoso sobre serpentinita (cuabal) | 6 | Charrascales cerrados |

| 29 | Matorral xeromorfo subespinoso sobre serpentinita (charrascal) | 6 | Charrascal cerrado |

| 19 | Matorrales indiferenciados, mayoritariamente secundarios y marabuzales, maniguas y pastos con matorrales, bosques secundarios muy degradados y ralos | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 40 | Matorrales sobre Arenita | 2 | Charrascal abierto |

| 35 | Monte Fresco | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 38 | Pinares de |

1 | Bosques siempre verdes de coníferas |

| 9 | Pinares de |

1 | Bosques siempre verdes de coníferas |

| 23 | Pinares de |

1 | Bosques siempre verdes de coníferas |

| 33 | Pinares de |

1 | Bosques siempreverdes de coníferas |

| 12 | Plantaciones de Pino | 1 | Bosques siempre verdes de coníferas |

| 14 | Plantaciones de Pino Jóvenes | 1 | Bosques siempre verdes de coníferas |

| 6 | Plantaciones Latifolias | 5 | Bosques mixtos |

| 15 | Plantaciones Latifolias Jóvenes | 4 | Bosque caducifolio de hojas anchas |

| 26 | Pluvisilva de baja altitud | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 31 | Pluvisilva Esclerofila Submontana sobre Mal Drenaje | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 24 | Pluvisilva Esclerófila Submontana sobre Serpentinita | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 25 | Pluvisilva Submontana sobre Comp. Metamórfico | 2 | Bosque siempreverde de hojas ancha |

| 43 | Sabanas naturales S.L | 9 | Sabanas |

| 37 | Saladares | 16 | Estéril o escasamente vegetado |

| 39 | Zonas desnudas y semidesnudas | 16 | Estéril o escasamente vegetado |

Anexo 3. (Table 7).

Table 7. - Conversión de clases para el Catastro Nacional

| Tipo de uso del suelo catastro nacional | IDUso | USGS24 | MODIS20 | USGS24+l | MODIS20+l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apoyo a la producción agropecuaria | 8420 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Apoyo a la producción silvícola | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 | |

| Asentamientos urbanos | 8010 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Asentamientos rurales | 8020 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Superficie ocupada por vertederos | 8340 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Instalaciones educacionales | 8600 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Instalaciones turística-recreativa | 8700 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Otras Instalaciones | 8900 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Autopistas | 8110 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Carreteras | 8120 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Avenidas | 8121 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Calles principales | 8122 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Calles secundarias | 8123 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Vías de interés específicos | 8130 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Ferrocarril público | 8210 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Ferrocarril cañero | 8220 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Ferrocarril industrial | 8230 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Otras instalaciones de transporte | 8290 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Aeropuertos | 8240 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Aeropuerto internacional | 8241 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Aeropuerto nacional | 8242 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Superficie de Instalaciones industrial | 8320 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Superficie de explotación minera | 8330 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 13 |

| Viveros y semilleros | 2900 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Caña de azúcar | 3000 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Cítrico | 2210 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Viveros y semilleros de cítricos | 2920 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Henequén | 1910 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Kenaf | 1920 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Tabaco | 1410 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Plátano | 2110 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Viveros y semilleros de frutales | 2960 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Otros cultivos temporales | 1900 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Pastos naturales | 4100 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Pastos y forrajes | 4200 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Forrajes temporales | 4300 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 12 |

| Producción pecuaria | 8410 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Arroz | 1210 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 12 |

| Cultivos varios | 1010 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| Viveros y semilleros de pastos y forrajes | 2980 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| Deforestada | 5060 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Otras no aptas | 8000 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Superficie ociosa (ganadería) | 4060 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 |

| Café | 2310 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Viveros y semilleros de café | 2930 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Cacao | 2410 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Viveros y semilleros de cacao | 2940 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Frutales | 2290 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Otros cultivos permanentes | 2910 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Viveros y semilleros de otros permanentes | 2990 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Bosques naturales | 5100 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Latifolias | 5220 | 13 | 2 | 13 | 2 |

| Coníferas | 5210 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 |

| Hídrica natural | 7100 | 16 | 17 | 28 | 21 |

| Embalses | 7200 | 16 | 17 | 28 | 21 |

| Canales | 7300 | 16 | 17 | 28 | 21 |

| Herbazal de ciénagas | 7400 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 11 |

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

AFRIZAL, T., y SURUSSAVADEE, Ch., 2018. High-Resolution Climate Simulations in the Tropics with Complex Terrain Employing the CESM/WRF Model. Advances in Meteorology, vol. 2018, ISSN 1687-9309,. DOI 10.1155/2018/5707819. [ Links ]

CAPOTE, R.P., y BERAZAÍN, R., 1984. Clasificación de las formaciones vegetales de Cuba. Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional, vol. 5, no. 2, ISSN 0253-5696. Disponible en: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42596743 [ Links ]

CENTELLA-ARTOLA, A., BENZANILLA-MORLOT, A., VICHOT, A., y MARTÍNEZ-CASTRO, D., 2020. Estimación del clima futuro en Cuba a partir de modelos climáticos. Informe de Resultado. Habana, Cuba: Instituto de Meteorología. [ Links ]

CENTELLA-ARTOLA, A., BEZANILLA-MORLOT, A., SERRANO-NOTIVOLI, R., VÁZQUEZ-MONTENEGRO, R., SIERRA-LORENZO, M., y CHANG-DOMINGUEZ, D., 2023. A new long term gridded daily precipitation dataset at high-resolution for Cuba (CubaPrec1). Data in Brief, vol. 48, ISSN 2352-3409. DOI 10.1016/j.dib.2023.109294. [ Links ]

CHU, D., SHEN, H., GUAN, X., CHEN, J., LI, X., LI, J., y ZHANG, L., 2021. Long time-series NDVI reconstruction in cloud-prone regions via spatio-temporal tensor completion. Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 264, DOI 10.1016/j.rse.2021.112632. [ Links ]

DELGADO-TÉLLEZ, R., y PEÑA-DE LA CRUZ, A., 2019. Cartografía de variables climáticas basada en gradientes, sistemas de expertos y SIG. Revista Cubana de Meteorología., vol. 25, no. 2, ISSN 0864-151X. Disponible en: http://rcm.insmet.cu/index.php/rcm/article/view/464/639 [ Links ]

HARDY CASADO, V., VILARIÑO CORELLA, C.M., NIEVES JULBE, A.F., FERNÁNDEZ CRUZ, S., ARIAS GUEVARA, M. de los Á., y PEÑA RODRÍGUEZ, E., 2021. Resiliencia local. Evaluación orientada a la reducción de riesgos por incendios forestales. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales, vol. 9, no. 3, Disponible en: https://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/698 [ Links ]

MOLINA-PELEGRÍN, Y., GEADA LÓPEZ, G., SOSA-LÓPEZ, A., PUIG-PÉREZ, A., RODRÍGUEZ-FONSECA, J.L., y RAMÓN-PUEBLA, A., 2021. Proyección del hábitat potencial de Magnolia cubensisurb. subsp. ubensisen el oriente de Cuba. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales , vol. 9, no. 2, ISSN 2310-3469. Disponible en: https://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/699. [ Links ]

NCAR, 2018. Weather Research and Forecasting Model ARW. Version 4 Modeling System User´s Guide. julio 2018. S.l.: Mesoscale and Microscale Meteorology Laboratory, National Center for Atmospheric Research. [ Links ]

PEÑA-DE LA CRUZ, A., DELGADO-TÉLLEZ, R., SIERRA-LORENZO, M., MORLOT, A.B., SAVÓN-VACIANO, Y., y RODRÍGUEZ-MONTOYA, L., 2023. Sensibilidad del WRF en topoclimas del oriente de Cuba. Revista Cubana de Meteorología, vol. 29, no. 4, ISSN 2664-0880.Disponible en: http://rcm.insmet.cu/index.php/rcm/article/view/811 [ Links ]

POSPEHOV, G.B., SAVÓN, Y., DELGADO, R., CASTELLANOS, E.A., y PEÑA, A., 2023. Inventory Of Landslides Triggered By Hurricane Matthews In Guantánamo, Cuba. GEOGRAPHY, ENVIRONMENT, SUSTAINABILITY, vol. 16, no. 1, ISSN 2542-1565, 2071-9388. DOI 10.24057/2071-9388-2022-133. [ Links ]

TADONO, T., ISHIDA, H., ODA, F., NAITO, S., MINAKAWA, K., y IWAMOTO, H., 2014. Precise global DEM generation by ALOS PRISM. ISPRS Annals of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, vol. II-4, DOI 10.5194/isprsannals-II-4-71-2014. Disponible en: https://isprs-annals.copernicus.org/articles/II-4/71/2014/isprsannals-II-4-71-2014.pdf [ Links ]

TORRES, I.C., y LORENZO, M.S., 2023. Evaluación del pronóstico cuantitativo de la precipitación del SisPI2.0. Revista Cubana de Meteorología [en línea], vol. 29, no. 2, [consulta: 21/10/2023]. ISSN 2664-0880. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://rcm.insmet.cu/index.php/rcm/article/view/765 . [ Links ]

VARGA, Á.J., y BREUER, H., 2020. Sensitivity of simulated temperature, precipitation, and global radiation to different WRF configurations over the Carpathian Basin for regional climate applications. Climate Dynamics [en línea], [consulta: 14/09/2020]. ISSN 0930-7575, 1432-0894. DOI 10.1007/s00382-020-05416-x. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00382-020-05416-x . [ Links ]

VICHOT-LLANO, A., MARTINEZ-CASTRO, D., BEZANILLA-MORLOT, A., CENTELLA-ARTOLA, A., y GIORGI, F., 2021. Projected changes in precipitation and temperature regimes and extremes over the Caribbean and Central America using a multiparameter ensemble of RegCM4. International Journal of Climatology, vol. 41, no. 2, ISSN 0899-8418, 1097-0088. DOI 10.1002/joc.6811. [ Links ]

WANG, X., TOLKSDORF, V., OTTO, M., y SCHERER, D., 2020. WRF based Dynamical Downscaling of ERA5 Reanalysis Data for High Mountain Asia: Towards a New Version of the High Asia Refined Analysis. International Journal of Climatology, DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6686. [ Links ]

ZAMORA FERNÁNDEZ, M. de los Á., y AZANZA RICARDO, J., 2020. Influencia de factores geográficos y meteorológicos en incendios forestales de las Tunas. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales , vol. 8, no. 3, Disponible en: https://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/639 [ Links ]

ZAMORA FERNÁNDEZ, M. de los A., AZANZA RICARDO, J., y BEZANILLA MORLOT, A., 2022. Impacto del cambio climático en la generación de incendios forestales en Las Tunas. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales , vol. 10, no. 2, Disponible en: https://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/729 [ Links ]

Received: October 30, 2023; Accepted: January 31, 2024

texto en

texto en