Introduction

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the traditional approach to education was left behind. It is necessary to devise and implement new educational strategies such as online, distance, or virtual learning, 1 which is why millions of teachers began to teach in front of a computer screen, changing their role from classroom learning to distance learning, confined to working from home and adopting a new challenge to quickly learn new technologies and put them into practice. On the other hand, the confinement exposed the weaknesses within the virtuality of teachers; however, the contingency made the vast majority of teachers, including inclusive teachers, improve their digital capabilities, although not at the desired pace and quality, because in the case of the latter, there is no evidence of being adequately prepared in the management and application of virtual technology tools that meet the special educational needs of students in inclusion. 2

Inclusive education dates back to 1990 as an ideology that criticizes the exclusion of students with disabilities through traditional systems of special education, 3 seeking an appreciation of individual differences, learning styles, academic levels, among other aspects that include valuing all students equally, promoting participation and eliminating discrimination. 4 The creation of international policies on inclusive education has increased the diversity of students in classrooms. Based on the Salamanca Statement, which indicates the access of people with special educational needs to regular schools, 5 we find that this type of education goes beyond the simple inclusion of students with special educational needs in regular schools because it focuses on the academic and socio-emotional development of all students, 6) providing equal opportunities to learn, without discrimination and respecting differences. 7

Educational inclusion is a guiding principle throughout the world, and it is regulated, leading to several challenges for teachers because they are central actors in the development of inclusive practices and need to learn how to respond to an educational needs of a diverse range of students, including those with special educational needs associated with disability. 8 Therefore, the knowledge and skills of the teacher are essential to practice pedagogy in inclusive education and manage classrooms with diverse students, providing teaching with exceptional strategies for the integral development of students, especially in those most vulnerable. 9

Making inclusive teaching effective requires the preparation of all teachers and taking a different approach to education, which involves identifying the components of effective approaches to teacher training and considering the situation, context, historical and political developments in their country's educational systems. 3 In this sense, educational inclusion and adequate response to diversity are objectives that teachers must continuously pursue, focused on providing special attention to the most vulnerable children and those at risk of exclusion, 10 thereby achieving their effectiveness, especially when involving teachers, students, parents and the community in general.

This COVID-19 situation impacts families through the imposition of isolation and social distancing measures. 11 In addition to this, school closures place an additional burden on parents to teach their children while meeting the demands of employment, household chores, and other caregiving responsibilities. 12 In this sense, the home is not the appropriate pedagogical place to function as a school (Espinoza Parra et al., 2020); however, for those parents of students with special educational needs, it is a challenge, which requires full-time attention and service, 13 and there is evidence that the burden on parents of children with disabilities is more significant than in the general population 14 which can affect the mental health of families since staying home from school can create a tremendous amount of stress. 15 Although homeschooling in this transition period is difficult, parents should consider that the education that takes place in their homes is essential for the child's development; therefore, parents should be aware that interacting in tasks, exercises, and activities with their children with disabilities implies a greater involvement from home. 16 However, many parents reported on the positive aspects of staying at home, such as spending time with their family and improving their relationships, establishing routines at home, using behavioral strategies, meditation, or social support to decrease stress during confinement. 13

The changes in the educational scenario have generated a depletion of teachers' physical and mental health due to the work overload that online teaching entails since it involves working long hours. 17 This unexpected change in teaching has led to work burnout and stress when facing this new challenge, as shown in the study by Besser et al., indicating that the transition to online teaching increases the level of psychological stress in teachers. 18) This pandemic situation allows teachers to adapt to a new teaching situation involving ICT, which will be fundamental after this crisis. 19 Likewise, a new teaching and learning paradigm is proposed for the future, where a conceptual and philosophical rethinking of the nature of teaching and learning, of the roles and connections between teachers and students, will be necessary. 20

The objective of this research was to systematize the pedagogical experiences of four inclusive female teachers in Peru concerning their pedagogical work in the times of COVID-19. The study was focused on five central analysis categories (teacher; school; educators, and parents; pandemic situation; and stress, coping, and perspectives) whose sustenance allows access to a new and significant casuistic knowledge resulting from the experiences, insights, and reflections of the teachers under study.

Methods

A phenomenological hermeneutic study with a qualitative approach allowed the educational agents to reflect on their personal experience and professional work 21 and the description and interpretation of the fundamental structures of the experience lived by the four participating teachers. The study was planned on the basis of the following three stages: descriptive, structural, and discussion.

In the descriptive stage, the theoretical, methodological, and ethical procedures of the study were planned. Technical documents such as letters of introduction and invitation to expert judges, letters of informed consent were prepared. Based on previous informative training, the participants were made aware of the importance of the problem under study and its objectives, scope, and educational and scientific relevance. Ethical intervention protocols, transversal to the research process, were proposed. As a technique for the collection of information, the structured interview was used through a questionnaire made up of 46 semi-structured questions distributed in five categories of analysis:

Teacher: initial contextualization, significances linked to ICTs, and the teacher's methodology about the inclusive student.

School: significances linked to the educational institution about inclusive students.

Students and parents: significances linked to inclusive students.

Pandemic Situation: significances linked to COVID-19.

Stress, coping and perspectives: significances linked to stress in times of COVID-19, Evaluation of situations related to being a teacher in COVID-19.

This was the starting point for an intervention focused on finding a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon that the four teachers were experiencing and how they observed the educational reality, amid the COVID-19, from their role and in the most authentic way possible; without neglecting their capacities, skills, motivations, and pedagogical convictions.

In the structural stage, self-training workshops were carried out to achieve the first approach with the teacher's understudy, to empathize and make them aware of the importance of the study, also to exercise the intervention protocols, to review the contingency plans, and to develop the competencies, abilities and investigative attributes, elemental to develop a technical intervention according to the declared methodology and its central objectives. Literature was located to give transversal epistemological support to the study: a professional search was carried out in high-impact databases such as Scopus, Springer, Web of Science, among others. In this same stage, the roles of the researchers were delimited, both inside and outside the field of study, being the subject-object and logic-dialogical relations a central element. The relevance and objectivity of the instrument were verified to correct biases, technicalities, inconsistencies, unnecessary repetitions, redundancies and achieve coherence and cohesion. After applying the instrument, the results were reflected upon, organized, and integrated according to the main categories declared in the descriptive stage. Finally, they were socialized privately with the teacher's understudy to reflect on their opinions and confirm their testimonies.

In the discussion stage, after processing the results of the interview in-depth, the results obtained during the research stage were contrasted with the results, discussion or conclusions of previous studies to find convergences, divergences, or new contributions and from them to establish a debate that generates the basic constructs of the new knowledge that will allow explaining the main particularities of the studied phenomenon. In the teacher category, the interpretation of the results is discussed to the subcategories initial contextualization, significances linked to the ICTs, and significances related to the teacher's teaching methodology to the inclusive student. In the school category, the interpretation of the results is discussed about the subcategories of significance linked to the Educational Institution concerning inclusive students. In the students and parents’ category, results discuss the significance of inclusive students and the significance of the parent. In the pandemic situation category, results related to significance associated with COVID-19 are discussed. In the category stress, coping, and perspectives, the results are discussed to the significance of stress in times of COVID-19 and the evaluation of situations about being a teacher in times of COVID-19.

The systematization and interpretation of the results of the interviews were carried out with the qualitative analysis software ATLAS.ti 9; open coding was used to capture the aspects that allow generating structures that explain the reality through the theoretical, empirical dialogue in an inductive process.

For ethical considerations, two fundamental ethical principles were assumed. 1. Informed consent: Teachers voluntarily supported their participation through a letter of informed consent where the limits of their participation were established. 2. Confidentiality and anonymity. 22 In addition, the researchers accepted the guidelines to safeguard the identity of the participants. Likewise, participants and researchers signed a binding document that recognized the right of both parties to know progress and results, in stages, of research.

Results

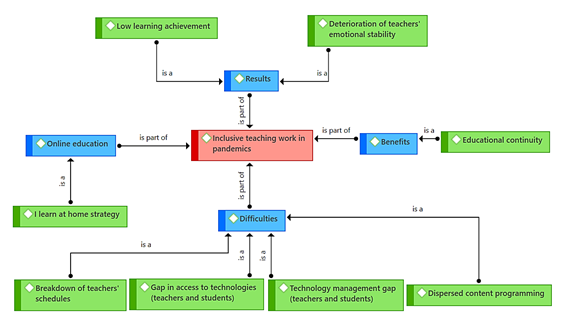

In figure 1, the participating teachers recognize that the “I learn at home,” with all its difficulties, has allowed educational continuity in times of pandemic. However, it presents difficulties such as gaps in access and management of technologies for both teachers and students. They also consider the rupture of teachers' schedules and problems in class schedules in the different means of implementation of online education. As a result of this process, there is a low school performance and a deterioration of the emotional stability of teachers.

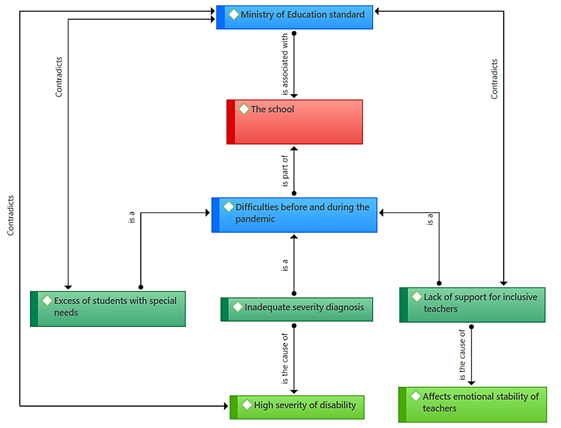

Figure 2 interprets the results of the school category. In this regard, difficulties are found, the same that have been present even before the pandemic, such as Inadequate diagnoses of the severity of disabilities in students, the same that should be in a special education system, the lack of support and support to inclusive teachers. These identified issues constitute transgressions to the Ministry of Education regulations.

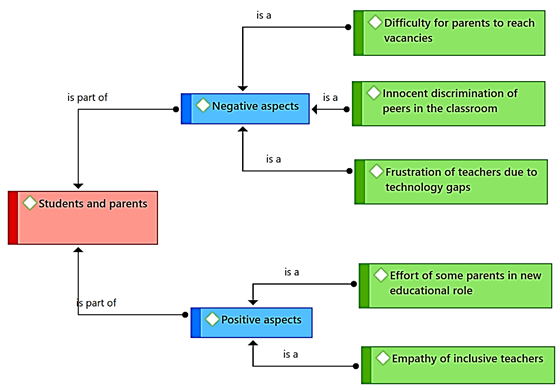

Figure 3 shows that there are negative aspects identified in this category. There are negative aspects such as difficulties for parents to enroll their children, discrimination of students against their peers with disabilities, frustrations of teachers due to technological gaps. Positive aspects have also been identified, such as an important effort by parents to assume a new role in their children's education and the empathetic attitudes of teachers towards children with disabilities.

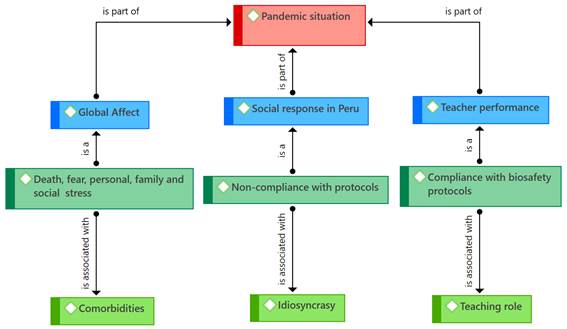

Figure 4 shows that the participants recognize the pandemic as a phenomenon with a global impact, which implies deaths, fears, frustrations, and personal, family, and social stress; this is aggravated by the comorbidities that people suffer from. In this context, the response in Peruvian society has been marked by non-compliance with protocols, mediated by a peculiarity related to a highly informal society. The teachers' response has been to comply with the biosafety protocols indicated by the World Health Organization and the Peruvian State.

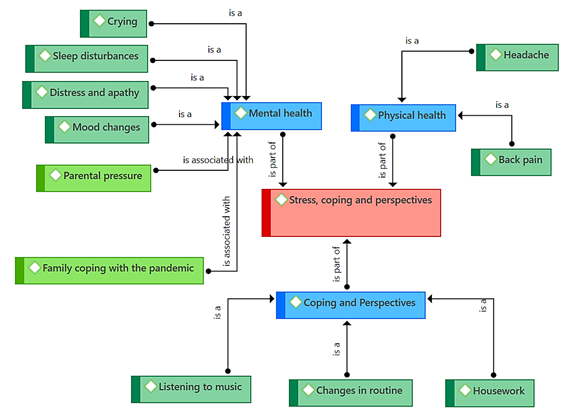

Figure 5 shows how family pressure in coping with the pandemic and parental pressure generated mental health problems in the teachers in pandemic contexts, manifesting in loss of sleep, anguish, apathy, and even crying, in addition to headaches and back pain. Situations like these have generated defense mechanisms orienting activities such as routine changes in housework and listening to music, allowing them to take impulse and face complex situations such as the pandemic with new strategies.

Discussion

Teacher category: The participants state that in this distance education, their work becomes affected because some students, regardless of their condition, do not have the economic means to connect to the virtual classes, hindering the normal learning of the programmed contents and neither do they have the necessary skills to use these tools to access their virtual classes. The research by Chung et al. found that students presented connectivity difficulties and scarce data for their broadband as a barrier to online learning. 23 This situation is not unrelated to that found in the present study. Teachers needed to demonstrate flexibility, adaptation and turn to tablets or smartphones as an emerging way out to solve it. Romero-Rodriguez et al. highlight the importance of mobile devices to mediate learning in pandemic situations, considering these equipment or devices as very useful contingent resources to not stop the educational process. 24 The four teachers indicate that this new way of working affects both students and themselves because it implies greater dedication and different strategies in this disruptive situation. Kucirkova et al. (2020) found that COVID-19 generated abrupt changes in all social activities, 25 which brought in parallel a new context for the intensive use of information and communication technologies, definitive to initiate an adaptation process that in the educational area is irreversible and cannot be postponed.

As for the significances linked to the ICTs, the teachers presented difficulties using these technological tools during the development of remote classes. The research conducted by Rap et al. warned that teachers need technical and pedagogical information on the ICTs to cope with teaching and learning online. 26 In that sense, the teachers highlight the limitations of connectivity as a barrier that limits the process of virtual teaching since not all of them have access to fast internet. Concerning connectivity via cell phones, they argue that many limitations must be overcome, such as the issue of collapsing batteries and cables due to overuse. To connect to the internet, they often need to sit near the Wifi modem, so they often work in places without the basic ergonomic conditions to demonstrate efficient teaching performance. The consequences of this situation are that they experience muscular problems, headaches, mental and physical fatigue, anxiety, and fear. 27 The teachers were also affected by the impossibility of buying a device during the most complex moments of COVID-19 because there were no economic resources or places to buy them. All these situations spotlight technical problems and access to technology, 27 but also problems of social inequality.

In Peru, COVID-19 unearthed long-standing social inequalities marked by unequal access to modern technology. In this sense, the teachers observe that students have access to quality technological implements, but they are not in the majority. In other words, not all students have access to educational materials, infrastructure, food, and technology, among others. However, given this precariousness, students are motivated to continue studying with the hope of facing a future full of opportunities 28 even though there are barriers in the handling of equipment because when parents with fewer possibilities manage to acquire electronic devices and state-of-the-art technologies that pave the way for their children's education, they have to face the fact that their children, and even they, do not know how to handle them properly.

Interestingly, they noticed that when the pandemic broke out, multiple Peruvian households had only one cellular device, which was used for teaching, work, and personal matters of the household members, causing continuous interruptions to the detriment of the optimal development of the students. From a pedagogical interpretation, the inclusive teachers were forced to implement and -in other cases- merge methodological strategies and even innovate many of them, given the same characteristics of this type of education. In Sá and Serpa's study, the need to increase the permanent training in the use of digital technology for teachers to improve and empower themselves in this new situation became evident, challenging with solid arguments the barriers that arose as a result of the pandemic, becoming opportunities to redesign the strategies, methods, evaluation through virtuality with a view to a different pedagogical future. 29

One of the teachers explained that before the pandemic, she gave an autistic child the responsibility of erasing the blackboard, giving the children the pens to mark their attendance, handling out the crayons for the work, helping to hand out the Qaliwarma (from Quechua, “breakfast for children”), and that the child fulfilled this responsibility progressively and positively. However, in this particular situation, pedagogical actions of this type could not be implemented and, therefore, deserved a methodological rethinking that meant an additional effort for the teacher. This educational action is ratified by Cretu & Morandau, who argue that educators, who are the main actors of inclusion, need to give immediate and creative answers to face the diversity of students with different educational needs. 8

Another teacher said she was working with a girl with mosaic-type Down syndrome, motor clumsiness, poor articulation of words and slow learning. This caused her additional difficulties compared to when the education was in a classroom. The teacher asks herself, “If it was difficult to move this child forward in a classroom setting, what will happen now when the learning situation is more complex?” In other words, how do we adapt the curriculum to provide an inclusive educational response to students in this pandemic? The teachers explain that their efforts range from providing the materials or resources considered by the Peruvian Ministry of Education for learning to downloading videos and sending them via WhatsApp to parents to make these audiovisual products serve as reinforcement to the curricular activities. The teachers state that it is necessary to look for spaces to have a greater approach with these children because the time assigned for the teaching is recharged and inadequate. In this sense, the “Aprendo en casa” (I learn at home) platform as a resource to support teaching has been useful for teachers despite the workload it generates. This platform is available in the authorized web of free access. Still, again, the limitation of access to the technology appears both for the teacher and the student or simply when the programming is interrupted (for congressional reasons, presentation of the national budget, vote of confidence...) in a schedule that the student is watching the program. The teachers have been adapting themselves to the needs of students to know how to communicate with them, if they are understanding or not. In short, they have had to adapt their traditional way of teaching to an online teaching. 30

About feedback on curricular content, the teachers emphasize that when assignments are sent late, they communicate with students to acknowledge and congratulate them on their progress, thus stimulating intrinsic motivation using verbal, written or visual language. When there is direct interaction with the children, the teachers ask: “how did you do this,” “what did you think,” “was it difficult,” “was it easy,” and depending on what the children answer, they ask other more complex questions. These questions, foreseen in Wilson's Feedback Ladder, round out teaching effectiveness because they provide useful information for developing new learning strategies. They assure that this type of feedback is decisive in verifying whether or not the student advances. This is confirmed by Nayak et al., who found that using individual and group strategies followed by feedback gave satisfactory results in socialized and group learning and reasoning and evaluation of the process. 31

One of the teachers exemplified the usefulness that she has found in the pictograms, this strategy allowed a continuous communication between her and an inclusive student: “the student is pointing at me, I send her a number, she represents it to me through concrete material, I present her with images, I start by numbering 1, 2 and she continues repeating the correlative numbering”. According to the teacher, the student has started to excel in expressing herself, and some words are understood. The experience of the inclusive teachers is ratified by the results found by Pourmousavi & Mohamadi Zenouzagh (2020) who found that personalized feedback produced better results than group feedback, because the students feel that their teacher is dedicated to commenting on their work in an exclusive way facilitating the teacher-student relationship and improving the levels of attention.

The teachers explain that in this pandemic scenario they have to attend to students until late at night, parents send homework without respecting schedules or agreements. They must evaluate daily and report results to students with suggestions or possible actions for improvement. A formative feedback is produced to guide the teacher's pedagogical actions to improve student competencies. 32 When they finish, they must start planning the next learning activity. At the end, they have less than six hours left to rest and start the next working day, showing that the work of the inclusive teachers under study exceeds their work schedule, which becomes more intense when to all the above mentioned, the obligatory, improvised and unexpected training are added, as well as their family dynamics. These work excesses -they explain- directly impact their emotional stability.

School category: the participants indicate that the capacity of the schools should determine the enrollment process according to the seating capacity of their classrooms, but sometimes these capacities are exceeded and those who make these decisions adduce a greater demand to the capacity of response. However, they violate the provisions of the Ministerial Resolution: Two 2 vacancies per classroom will be reserved for students with SEN (Special Educational Needs) associated with mild or moderate disability for up to fifteen 15 calendar days from the start of enrollment. (...) If the vacancies available in the classrooms are covered, the Director of Educational Institution, the person in charge of the program, or whoever is acting as such, must issue a document expressing the absence of vacancies and give it to the parent, guardian, curator, or accredited representative of the NNA requesting the registration. 33

In practice, a presumed transgression of the Ministerial mentioned above Resolution is observed because up to five students per classroom can still be found. As an aggravating factor, without the prior diagnosis based on the awareness of prospective classmates, parents, and teachers in charge before their admission. On the other hand, they attend to students with severe cases, children with mental retardation and others with aggressive behavior who, because of these characteristics, should not receive education in regular classrooms, but in Special Basic Education. In this sense, the inclusive teachers consider that according to Ministerial Resolution No. 0271-2006-ED, Objective 2.1., it is necessary to “Adequate the organization and operation of Special Basic Education Centers - CEBE, to provide comprehensive quality and timely training for students with severe disabilities or multiple disabilities”. 34 Therefore, the teachers ask themselves: “why are students with severe disabilities currently attending Regular Basic Education institutions? They add that not a few administrators avoid their responsibility towards inclusive students. This situation causes teachers to assume an administrative role that generates more work overload and stress, the consequences of which were mentioned in previous paragraphs.

Finally, the inclusive teachers refer that the necessary support in inclusive education, in charge of the Support and Advisory Service for the Attention of Special Educational Needs (SAANEE in Spanish) which should be permanent at early childhood and primary education, unfortunately does not fulfill this responsibility or the support offered by the SAANEE is insufficient. This is how one of them expresses it: “...in my experience neither before nor now do I receive the support of the SAANEE”, despite what is established by Ministerial Resolution:

The Special Education Center, which from now on will be called the Special Basic Education Center - SBEC (CEBE in Spanish), will constitute the “Support and Advisory Service for the attention of students with special educational needs”, (...) as an itinerant operational unit, responsible for guiding and advising the management and teaching staff of inclusive educational institutions of all levels and modalities of the Educational System and of the SBEC to which it belongs, for a better attention of students with disabilities, talent and/or giftedness (Article 5.9). 34

Students and parents’ category: the participants claim that, at the beginning of this new mode of study for inclusive students, other regular students demonstrated a kind of innocent discrimination to their inclusive peers, through expressions such as “...he can't because he's a baby...”, “...he's still little...”. These signs of discrimination have been found in other learning environments affecting inclusive children even more in this pandemic. 35 Following teacher intervention, students began to correct this discriminatory perception by demonstrating positive changes in their attitudes. Actions such as this attest to a good relationship between the four teachers and their inclusive students, ensuring a very good relationship and communication with them and every time they observe the progress, as well as their expressions of student satisfaction, they find additional motivation to continue with the educational process despite the objective and subjective difficulties of the process.

The teachers assure that empathy towards the students has also been essential within this whole process, because their vocation impulses them to feel the otherness. In their own words: “to be the voice of that deaf student, who cannot express himself, who cannot understand”. The teachers identify themselves with the needs of their students, not only those required by the child in their environment, but also in terms of activities or questions resulting from the training process. They argue that all educational institutions should receive inclusive children, without restrictions or obstacles to develop their abilities. They state that “many parents are left without a vacancy for their children with special educational needs because, although they stay up to register their children, very often it is complex and impossible for them to do so.” From this reality we can deduce the transgressions of the ministerial resolutions that have been systematized in the previous section. This reality is not exclusive to Peru, but also to other places where school children are segregated by various situations such as the condition of belonging to the group of students with special educational needs, making it difficult for them to have free access to schools, a fact that is unconceivable in first world societies. 36

The inclusive teachers' perceptions of how parents of children with these skills have responded to COVID-19 can be summarized as follows: “We have not studied to be teachers; it is not our obligation”. With this pandemic, the role of parents deserves special reflection, since this role has made these parents protagonists within the educational process. However, they are still unable to assimilate this protagonism. It is worth noting that one of the roles of the parent is to educate through norms that allow the child to grasp basic values and develop in a harmonious and healthy coexistence; 37 however, they are not in a position to use the methodological and didactic resources of the teacher as an educational transforming entity. 38 This situation could generate deep frustration beyond the literal, because the parent is developing a new role that was not even imagined months ago. On the other hand, the task of the inclusive teacher shows traces of frustration and hopelessness in the face of a disruptive and threatening reality when facing the barriers of new technologies, the lack of support and commitment of some parents, the problem of reinventing new strategies for inclusive children that already constituted a permanent challenge in the classroom and that becomes a vortex in this new situation, or the pain of those parents who have lost a family member due to the pandemic and emotionally are not ready to contribute better to the education of their children. However, it is not all chaos because other parents cooperate to raise awareness of the child's problem, which can ultimately facilitate intervention and appropriate pedagogical strategies in the inclusion process.

It is presumed that no parent is prepared to have a child with special educational needs, much less to influence his or her schooling, which is demonstrated through their overprotective and compensatory attitude, to demonstrate to themselves and others that the child has no limitations. They do not understand that the child must have autonomy within their limitations. The teachers add that certain parents, demonstrating an overprotective attitude during the virtual classes, end up carrying out the activities that correspond to the child. With this, they only achieve a deficient performance in their children's learning process. In contrast, other parents take a leading role in the educational process, making their situation a tool that benefits their child and becomes involved in achieving their child's goals. Alinsunurin's research found that parental involvement in inclusive schools is linked to the motivation that can be generated by the learning climate, 39) even though this situation is not always positive, but sometimes you will find controversial parents who become additional challenges to the inclusive education of their children.

Pandemic situation category: teachers are aware that this disease continues to strike societies worldwide regardless of race, sex, economic level, among others; causing death, restlessness, frustration, fear and personal-family-social stress. As an aggravating factor, its effect has been pernicious for people with respiratory diseases, diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and older adults. This situation, as in Peru, has led to lifestyle changes in Filipino teachers due to the fears produced by the pandemic. However, it has also served as an incentive for them to face this new reality, even though susceptibility and fear are the order of the day. 40

The teachers claim to meticulously comply with the biosecurity protocols recommended by the WHO and imparted by the Peruvian State through authorized means: hand washing, cleaning and disinfection of surfaces, use of masks, and social distancing, as an attempt to stop the massive spread of infection and the collapse of health institutions. However, the idiosyncrasies and psychology of Peruvians were not effectively anticipated and what was efficient in other contexts, it was and continues to be ineffective in Peru. It is evident that the prevention of this disease is closely linked to people's behavior within their own socio-cultural dynamics; therefore, social and cultural factors must be incorporated into future analyses, prevention campaigns and health promotion. 41

Stress, coping and perspectives category: teachers claim that this pandemic has brought them drastic changes in their professional and personal lives, experiencing some symptoms that were not usual before the pandemic, such as headache, backache, mood swings, sleep disturbance, listlessness and feeling of anguish, even crying of helplessness; one of them expressed: “the first months I even cried.” This fact highlights the mental health implications of this situation for the teachers. Unfortunately, the educational institutions they represent were not prepared to face this situation. 42 These stressful levels increased with the uncertainties caused by the parents, who communicated to ask questions that exceeded the teachers’ functions to share personal problems such as family violence, separation of couples, sick and dead relatives by COVID-19, among others, becoming a real chaos for them: “I wanted to throw in the towel” - said one of the teachers.

To live with psychological stress, the need to appeal to new ways of understanding reality is evident, taking advantage of the new opportunities for pedagogical development that are also inherent to the process. Paradoxically, Wong and Moorhouse found that this pandemic strengthened the motivational state of teachers, 43 who showed greater commitment to their academic work, providing their students with navigation instruments under difficult and dark circumstances.

In short, these situations described by the teachers served as motivation to improve their teaching and learning strategies in this new reality. On the other hand, to cope with this situation, they claim to have resorted to attitudes that were not present before the pandemic, such as turning on the television, listening to music, and entertaining themselves by cleaning their homes, among others. Taking these attitudes is understandable and is consistent with a similar attitude taken by some Filipino teachers who participated in the study proposed by Talidong and Toquero, who used social networks to communicate with their friends, students and colleagues and also spend time interacting with their loved ones on social networks to relieve their anxiety during confinement. 40

Conclusions

The economic limitations of inclusive students’ parents, their impossibility to acquire adequate technological equipment, and connectivity problems limit the normal learning of these children in times of COVID-19 and especially the teacher's performance. This causality is also expressed through the lack of opportunities and the social inequalities in Peru. These are evidence of a lack of educational policies aimed at guaranteeing economic support that includes both the implementation of new technological resources and the renewal of those already obsolete.

The formative work of the inclusive teacher exceeds his or her working hours, causing an overload that is exacerbated by mandatory training and the family dynamics themselves. Because of this, it is necessary to make adjustments in the pedagogical and family environments that allow them to adapt to the new reality without affecting their mental health. These adjustments respond to a new time management to meet the new educational demands of inclusive students in this pandemic phase. Feedback on the activities of inclusive students rounds out the effectiveness of inclusive teachers. It forms the basis for structuring questions with other levels of complexity needed to enable the progressive advancement of these students.

In general, educational institutions (both public and private) must respect and enforce the policies of the Ministry of Education concerning the admission and enrollment processes of these students. In particular, the fact that there are institutions where the capacity of children with different abilities per classroom exceeds the limit outlined in MR No. 665-2018-MINEDU, 2018, evidences a transgression of the regulations of the Peruvian Government about these children. It is another transgression to what the Peruvian Government regulates through the Ministerial Resolution No 0271-2006-ED that a teacher, in the same classroom (whatever the reason), attends to regular students, with mild and moderate disabilities together with children who present severe or multiple disabilities. No attribution made to this situation, i.e. lack of knowledge of rules, late or flawed or incomplete diagnoses, irresponsibility of parents, lack of institutional demands, among others, justify these transgressions.

In the face of possible manifestations of discrimination (conscious or unconscious), from regular to the inclusive students, it is necessary to cooperate with those who discriminate, the mediation of teachers and parents. In all cases, it is essential to develop empathy, which is a determining factor in entering into otherness and positively influencing the development of an appropriate climate where respect for difference is the key.

Parents must definitively assimilate that the current pandemic has modified their role within the educational process of their children; therefore, they must be actively involved in the process in permanent coordination with the teacher.

The four inclusive teachers are aware that COVID-19 affects and continues to affect people worldwide, which has led to abrupt changes in their lifestyles by implementing WHO-endorsed biosecurity protocols established to prevent infection, safeguarding their lives and those of their families.

The workload, having the skills for the optimal management of ICTs for educational purposes, socioeconomic barriers, and the complex relationship, especially with parents and family roles, are not balanced. This causes alterations in teachers' personal and professional dynamics, which are expressed through symptoms such as headaches, back pain, mood swings, sleep disturbance, listlessness and feelings of anguish, and even crying of helplessness due to lack of training. These symptoms must be taken into account and take the necessary preventive measures to carry out their educational role without affecting their mental health.