INTRODUCTION

The important events in the Winkler's life

Clemens Alexander Winkler (Figure 1) known simply as Clemens Winkler was called “the outstanding inorganic chemist of his time” (Smith, 1949, p. 256). He “made brilliant contributions both to pure and applied chemistry” (Weeks, 1956, p. 689). One hundred and seventeen years have passed since his death, but in that time little has appeared in the literature about this very interesting man. Among his most important scientific achievements, the American chemist Henry Monmouth Smith (1868-1950) mentioned in his 1949 book:

Prepared metallic cobalt in quantity. Determined the atomic weight of indium. … Introduced the term “normal weight” in volumetric analysis and the test for carbon monoxide by palladium chloride; determined sodium hydroxide in the presence of alkali carbonates. … After working day and night for several months he discovered a new element which he named germanium. … Reduced oxides with magnesium, and prepared hydrides of metals. Developed the Contact Process for sulfuric acid … Improved gas analysis and invented the three-way stopcock (p. 256).

Clemens Winkler was born in Freiberg (Kingdom of Saxony) on December, 26, 1838, and he was the son of Kurt Alexander Winkler (1794-1862), a chemist and metallurgist who studied under the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848), and his wife Elmonde Antonie, née Schramm (1810-1897) (Winkler, 1954, p. 11).

In April 1851 he went to the Gymnasium in Freiberg. From 1852 to 1853, he attended the Realschule in Dresden. In the years 1855-1856, he continued his education at the Gewerbschule in Chemnitz (Winkler, 1954, pp. 14-15). In 1857, he began his three-year (1857-1859) studies at the Königlich Sächsische Bergakademie (Royal Saxon Mining Academy) in Freiberg (Haustein, 2011b, p. 141; Weinert, 2020, p. 9; Prokop, 1954, p. 94). At this academy, he became interested in chemistry, especially mineral chemistry, which he dealt under the mineralogist August Breithaupt (1791-1973) (Anonymous, 1904, p. 900).

On October 1, 1859, he was employed as Akzessist at the Königlich Sächsische Blaufarbenwerk Oberschlema and on Ocotber 1, 1862, he began working as a metallurgical chemist at Privatblaufarbenwerkes Pfannenstiel (Pfannenstiel Private Blue Dye plant) at Aue (Haustein, 2011, p. 141; Prokop, 1954, p. 94).

On January 8, 1863, he married Minna Laura, neé Pohl (1843-1891) (Papperitz, 1904, p. 5; Prokop, 1954, p. 94; Winkler, 1954, p. 24). The spouses had six children: four sons and two daughters (Brunck, 1906, p. 4498).

In 1864, he presented two of his publications as a dissertation at the University of Leipzig: Ueber Siliciumlegirungen und Siliciumarsenmetalle (About alloys of silicon and silicon/arsenic metal compounds) (Winkler, 1864a) and Die maassanalytische Bestimmung des Wassers in organischen Flüssigkeiten (The Analytical Determination of Water in Organic Liquids) (Winkler, 1864b). On February 7, 1864, he received his Ph.D. (Haustein, 2011, p. 141; Prokop, 1954, p. 94).

On September 1, 1873, he was appointed Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the Mining Academy in Freiberg. He was the successor of Theodor Scheerer (1813-1875).

Leroy Wiley McCay studied in Germany for four years, first in Freiberg in 1879. There he attended lectures by Winkler, who he describes in his article (1930) as follows:

He was in his early forties, of moderate height, thick-set, wore a short dark beard … He had an attractive face, an engaging smile, and his voice, while low, had a peculiar penetrating power. His lectures on general as well as applied chemistry were extraordinarily gripping, for he had the power to communicate to his hearers the enthusiasm for the science which he himself possessed. He made his experiments himself and very rarely called upon an assistant for help. … His German was simple, straightforward … He knew little French and less English, but he was a master of his own language. His good nature, his winning manner, his generosity, his bonhomie, and his keen social instinct captured the love of all, students, colleagues, and fellow citizens. In my day he was the most popular man in Freiberg (pp. 1086-1087).

On September 2, 1896, after Theodor Richter's (1824-1898) resignation, Winkler was appointed Director of the Mining Academy, which he headed for three years, until to autumn 1899 (Brunck, 1906, p. 4515; Prokop, 1954, p. 95).

On November 30, 1901, he was appointed to the editorial board of the Zeitschrift für angewandte Chemie. In the summer of 1902, due to health problems, he resigned from work at the Academy and on August 12 he moved to Dresden (Prokop, 1954, p. 96).

On October 8, 1904, he died of lung cancer (Brunck, 1906, p. 4516). Erwin Papperitz (1904) wrote about his funeral as follows:

On October 11th, Winkler was solemnly buried to eternal rest in the Trinitatisfriedhofe zu Dresden [Trinity Cemetery in Dresden] amid moving manifestations of mourning on the part of all those who had learned to love and respect him.The great scholar, the loyal advisor and friend of the miners and huts, has "done his last shift". Now the eternal light of truth shines for him, which he had so eagerly investigated in life (p.12).

Winkler's participation in the scientific celebration in Berlin

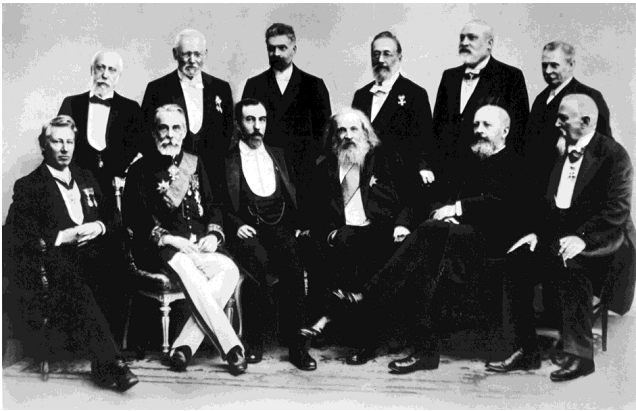

On March 19-20, 1900, Winkler took part in the Berlin conference devoted to the 200th Anniversary of the Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences). Figure 2 is a photography made during this celebration (“200th Anniversary of Berlin”, 1900). The American biochemists Benjamin Harrow (1888-1970) inserted this photo on the one of first pages of his book entitled Eminent Chemists of Our Time. He also wrote that it “showing several eminent chemists was taken at one of the international scientific gatherings” (Harrow, 1920, p. 8).

Photograph was published by Harrow thanks to the kindness of the Dutch chemist Ernst Julius Cohen (1869-1944) (Donnan, 1948). Winkler is second from the right in the second row; to his left is the British chemist and historian of chemistry Sir Thomas Edward Thorpe (1845-1925) (Tutton, 1925; Sztejnberg, 2021c). To his right are the German chemist Hans Heinrich Landolt (1831-1910) (Oesper, 1945), the Finnish chemist and historian of chemistry Edvard Hjelt (1855-1921) (Kauffman & NiiNistö, 1998), the Danish chemist Sophus Mads Jørgensen (1837-1914) (Kauffman, 1992), and the German chemist and historian of chemistry Albert Ladenburg (1842-1911) (Sztejnberg, 2021b). Seated from the left to right in the front row are van’t Hoff, the Russian - German chemist Friedrich Konrad Beilstein (1838-1906) (Sztejnberg, 2021a), the British chemist Sir William Ramsay (1852-1916), who found neon, argon, krypton, and xenon in air and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 (Tilden, 1918), the Russian chemist Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev, who discovered the Periodic Law in 1871 (Boeck & Zott, 2007; Sztejnberg, 2018), the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer (1835-1917), who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1905 (Baeyer, Villiger, Hottenroth, & Hallensleben, 1905), and the Italian chemist Alfonso Cossa (1833-1902) (Kauffman & Molayem, 1990).

Winkler’s works

The list of Winklers’s works includes one hundred and thirty papers published over a 45-year period, from 1859 to 1904. There are the articles published in Germany, among other in the Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, Zeitschrift für analytische Chemie and Journal für Praktische Chemie. Between 1859-1900, he published 32 articles in the field of analytical chemistry. Forty-seven of his papers in the field of general chemistry and inorganic chemistry appeared in print in the years 1863-1904. In 1869-1900, he published 33 technological articles. The nine papers that were published in the years 1872-1900 were devoted to chemical apparatus. Nine of his articles from 1875-1902 dealt with a variety of topics (Lissner, 1954, pp. 63-68).

Winkler's first work concerned the composition of the condurrite (Winkler, 1859). In the next eight years he focused his research on analytical as well as general and inorganic chemistry. In one of the articles from 1864 he described Thompson's separation method for cobalt and nickel (Winkler, 1864c). Two of his other papers in the same year dealt with cobaltic acid (Winkler, 1864d; Winkler, 1864e). In the years 1865-1867, indium became the object of his research interests (Winkler, 1865; Winkler, 1867a).

In 1875, he developed an industrial method for the production of sulfuric anhydride, which marked the beginning of the contact method for the production of sulfuric acid (Winkler, 1875a). On June 7 and 8, 1900, he participated in the general meeting of the Association of German Chemists in Hanover. There he gave a lecture entitled Die Entwickelung der Schwefelsäurefabrikation im Laufe des scheidenden Jahrhunderts (The Development of Sulfuric Acid Production in the Course of the Late Century). This lecture was published in the Zeitschrift für angewandte Chemie in the same year. He wrote there, among other on his invention of the contact method in the production of sulfuric anhydride (sulfur trioxide) in the mid-1870s (Winkler, 1900, p. 738). The Polish chemist Józef Gruszkiewicz (1904) wrote briefly about this method in his article:

Already in 1875, the freshly deceased Klemens Winkler announced his dissertation on obtaining fuming sulfuric acid by decomposing concentrated acid at high temperature into SO2, O and H2O and converting the next SO2 to SO3 with catalysts (pp. 865-866).

Mike Haustein (2017) also wrote about this contact method:

In the winter of 1874/75, Clemens Winkler constructed a laboratory system in the Chemical Institute of the Bergakademie Freiberg, with which he simultaneously thermally decomposed Englische Schwefelsäure [English sulfuric acid]. … Winkler chose platinum as the contact substance. But he also experimented with palladium, iridium and some metal oxides. In order to obtain the largest possible surface, the Freiberg professor had to apply the precious metal in finely divided form to a porous carrier material. The equally required heat resistance made the choice of asbestos wool. The fibrous material was first impregnated with a soda-alkaline platinum chloride solution, to which an amount of sodium formate sufficient to reduce the platinum was added, the platinum precipitating very finely on the asbestos carrier. The pasty mass was washed extensively and then dried by heating in a water bath. The noble metal content of the catalyst could easily be controlled by the concentration of the platinum chloride solution. At first, Winkler worked with around 8%. In the technical process, a 25% platinum content ultimately proved to be particularly effective. The manufacturing process for the catalytic converter was patented in 1878 ... (pp. 168-169).

It is believed that on February 8, 1886, Winkler discovered germanium. On that day, the editors of the Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft received his article in which he informed about the discovery of this chemical element (Winkler, 1886a). He wrote about this discovery as follows:

After several weeks of laborious searching, I can today say with certainty that the argyrodite contains a new element very similar to antimony, but sharply differentiated from it, to which the name "Germanium" may be added (p. 210).

On July 6, 1886, his second article entitled Mittheilungen über das Germanium (Communications on Germanium) was published in the Journal für Praktische Chemie (Winkler, 1886b).

His last paper entitled Radioactivität und Materie (Radioactivity and Matter) was published in 1904 in the Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (Winkler, 1904).

Winkler's books on chemistry

Almost all of Winkler's books are written in German. Only his textbook has been translated into other languages. His first book under the title Untersuchungen über die chemische Vorgänge in den Gay-Lussac'schen Condensationsapparaten der Schwefelsäurefabriken (Investigations into the Chemical Processes in the Gay-Lussac Condensation Apparatus in the Sulfuric Acid Factories) was published in 1867 (Winkler, 1867b).

In 1871, he was a editor of the book written by his father entitled Geschichtliche Mitteilungen über die erloschenen Silber-, Blei- und Kupferhütten des Erzgebirges und Vogtlandes. (Historical Information about the Extinct Silver, Lead and Copper Smelters in the Ore Mountains and Vogtland (Winkler, 1871). Four years later, he wrote three chapters entitled Wismuth, Arsen, Antimon (Bismuth, Arsenic, Antimony), which were published in a book edited by August Wilhelm Hofmann (1818-1892) (Winkler, 1875b).

In 1876, his book entitled Anleitung Zur Chemischen Untersuchung Der Industrie-Gase. Qualitative Analyse (Instructions for the Chemical Investigation of Industrial Gases. Qualitative analysis) was published by J. G. Engelhardt'sche Buchhandlung in Freiberg (Winkler, 1876). A year later, the second volume of this book on quantitative analysis was published (Winkler, 1877).

His book entitled Die Massanalyse Nach Neuem Titrimetrischem System. Kurzgefasste Anleitung Zur Erlernung Der Titrirmethode, Der Chemischen Anschauung Der Neuzeit Gemäss (The Mass Analysis According to the New Titrimetric System. Brief Instructions for Learning the Titration Method, the Chemical View of Modern Times) appeared in 1883 (Winkler, 1883a). In the same year, his lecture at the Second General German Miners' Days in Dresden, entitled Wirkt die in unserem Zeitalter stattfindende Massenverbrennung von Steinkohle verändernd auf die Beschaffenheit der Atmosphäre? (Does the Mass Burning of Hard Coal Taking Place in Our Age Change the Nature of the Atmosphere?) was published in Freiberg (Winkler, 1883b).

The first German edition of his Lehrbuch Der Technischen Gasanalyse. Kurzgefasste Anleitung Zur Handhabung Gasanalytischer Methoden Von Bewährter Brauchbarkeit (Textbook of Technical Gas Analysis. Brief Instructions for Handling Gas Analytical Methods of Proven Usefulness) appeared in 1885 (Winkler, 1885a). Seven years later, in 1892, the second edition of this book was published (Winkler, 1892). The third edition was published in 1901 (Winkler, 1901). The fourth and fifth editions were published after Winkler's death, in 1919 and 1927, respectively, under the editorship of Otto Brunck (1866-1946). A reprint of the 1892 edition appeared as an online resource in 2019 (Winkler, 2019).

The first English edition of this book under the title Handbook Of Technical Gas-Analysis, Containing Concise Instructions for Carrying Out Gas-Analytical Methods of Proved Utility was published in 1885 in London. The translator was George Lunge (Winkler, 1885b). In the translator's preface he wrote:

EVERY one who has to make gas-analyses for technical purposes is aware that Professor CLEMENS WINKLER is the founder of technical gas-analysis as a distinct branch of analytical Chemistry. A few such processes were, of course, previously known and practised; but Winkler was the first to draw attention to the importance of this subject, to invent suitable apparatus, and to elaborate a complete system of qualitative and quantitative technical gas-analysis…, containing a vast number of new observations and methods, along with a very complete description of the work already done in the same direction by others (p.iii).

The second English edition of this book under the title Handbook Of Technical Gas-Analysis appeared in 1902 in London (Winkler, 1902).

The French (1886) edition of this textbook was published in Paris. The translator was Charles Blas (1839-1919), professor at the University of Louvain (Winkler, 1886c).

The first edition of his book entitled Praktische Uebungen in der Maassanalyse. Anleitung zur Erlernung der Titrirmethode (Practical Exercises in Dimensional Analysis. Instructions for Learning the Titration Method) was published in 1888 (Winkler, 1888). The second edition of this book appeared 10 years later (Winkler, 1898) and the third was published in 1902. The fourth and fifth editions were published in 1910 and 1920, respectively, under the editorship of O. Brunck.

In 1900, his lecture at the General Miners' Day in Teplitz (1899), entitled Wann endet das Zeitalter der Verbrennung? (When does the Era of Burning End?) was published in Freiberg (Winkler, 1900).

Winkler's correspondence with some great chemists

The Russian-German chemist Victor von Richter (1841-1891) (Sztejnberg, 2020) became the first Russian correspondent-chemist of the German Chemical Society (Kaji, 2003, p. 204). In the years 1869-1872 he sent twelve reports to the journal of this Society Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft about activities of the Russian Chemical Society.

Richter's correspondence from two meetings of the Russian Chemical Society, held on November 5 (17) and December 3(15), 1870, brought the full version of the Mendeleev Periodic Table (Richter, 1870, p. 992). Richter reported there that Mendeleev had to change the atomic weights of uranium, thorium, cerium and indium in building his table. He also wrote that, following the logic of his Periodic Table, Mendeleev predicted the existence of yet unknown elements: ekabor (Eb), ekaalumini (El) and ekasilitsii (Es). He cited Mendeleev's predictions about the physicochemical properties of these elements: their atomic weights, specific densities, atomic volumes, and the characteristics of their chlorides and oxides. At the end of his correspondence, Richter (1870) wrote:

Interessante Prognosen, wenn es gelänge eines dieser Element wirklich zu entdecken! Der Weg dazu wäre durch die a priori vermutheten Eigenschaften angezeigt” (Interesting prognoses, if one of these elements could really be discovered! The way to do this would be indicated by the properties assumed a priori) (p. 991).

On August 27, 1875, French chemist Paul Emile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1838-1912) discovered predicated by Mendeleev ekaalumini and named it gallium (Lecoq de Boisbaudran, 1875, pp. 493-495).

Mendeleev’s prognosis concerning an existence of ekabor also became the truth (Mendeleev, 1958, pp. 90-91). This element was discovered by Swedish chemist Lars Frederic Nilson (1840-1899) in 1879 and named scandium (Nilson, 1879, pp. 645-648).

Discovery of germanium by Winkler decisively confirmed correctness of the Periodic Table of the Elements defined by Mendeleev (Brush, 1996, p. 605; Haustein, 2011a, pp. 140-144; Smith, 1949, p. 256; Winkler, 1886, pp. 210-211). In a lecture (Winkler, 1897a, p. 242; Winkler, 1897b, pp. 15-16) held by him on January 11, 1897, in the German Chemical Society at Berlin ), he said:

This discovery [germanium] was not due to the concurrence of favorable circumstances or to a happy accident; it resulted from researches undertaken because of theoretical previsions, and the agreement between the predicted and real properties was such that Mendelejeff considers the discovery of germanium the principal justification of the law ot periodicity. … The success of the bold speculations of Mendelejeff allows us to affirm that the elaboration of the periodic system is a great forward step for science. In the course of only fifteen years all the predictions of the Russian chemist have been confirmed, new elements have been placed in the gaps which he left in his table, and there is reason to hope that it will be the same for those which still remain in the natural system (p. 242).

Richter, in a letter to Winkler dated February 25, 1886, published in Russian by the German chemist Anton Lissner (1885-1970), Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the Bergakademie Freiberg (1945-1955) (Lissner, 1957, p. 51) as well as by the Russian chemist and historian of chemistry Yuri Ivanovich Solov'ev (1983, p. 270), informed him:

что германий, название которого Вы должны сохранить как фактический его отец есть предсказанный Менделеевым элемент экасилиций, Es = 73, наинизший гомолог олова, стоящий в первом большом периоде между Ga (69,8) и As (79,9) … Экасилиций элемент, которого мы ждем с величайшим напряжением, и во всяком случае ближайшее исследование германия явится самым определенным experimentum crucis для периодической системы (that Germany, the name of which you must keep as its actual father is the predictions of Mendeleev, the element ekasilici, Es = 73, lowest tin homologue, standing in the first large period between Ga (69,8) and As (79,9) … The Ekasilici element we are waiting for with the greatest strain, and in any case, the next study of germanium will be the most definite experimentum crucis for the periodic system).

At the Museum of D. I. Mendeleev in St. Petersburg stores several of Winkler's letters to Mendeleev. Two of them were published by the Russian chemist and historian of chemistry Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Makarenya (1930-2015) in 1966 in the Russian journal Khimiya i zhizn' (Makarenya, 1966, pp. 55-56). Winkler wrote to Mendeleev in a letter dated February 26, 1886:

Милостивый государь! Позвольте мне препроводить Вам при сем отдельный оттиск сообщеня, согласно которому я обнаружил в найденном здешнем серебряном минерале новый элемент германий. Первоначально я был того мнения, что это элемент заполняет имеющийся в столь чрезвычайно остроумно составленной Вами периодической системе пробел между сурьмой и висмутом, т. е. что он, следовательно, представляет Вашу экасурьму; oднако все указывает на то, что здесь мы имеем дело c предсказанным Вами экакремнием. Я надеюсь вскоре иметь возможность сообщить Вам подробности относительно нового чрезвычайно интересного тела; сегодня я ограничусь тем, что уведомлю Вас об этом новом торжестве Вашего гениального исследования и засвидетельствую Вам свое высочайшее почтение. Клеменс Винклер 26 февраля 1886 г. (Your Majesty! Allow me to transmit to you in this separate reprint of a report according to which I have discovered a new element, germanium, in a silver mineral found here. Initially, I was of the opinion that this element is filled with the gap between antimony and bismuth in a very ingeniously compiled by you periodic table, that is, that it, therefore, represents your ekaantimony; however, everything points to the fact that here we are dealing with the ekasilitsii predicted by you. I hope soon to be able to give you details on a new extremely interesting body; today I will confine myself to informing you of this new triumph of your ingenious research and to pay you my highest respect. Clemens Winkler February 26, 1886) (p. 55).

On March 7, 1886, Mendeleev announced that he had received this letter at a Meeting of the Chemical Department of the Russian Physicochemical Society and in the April issue of the journal of this Society, Winkler's article entitled Germanium, a new metalloid was published (Makarenya, 1966, p. 55).

On March 1, 1886, Mendeleev sent a congratulatory telegram to Winkler. The Russian chemist and historian of chemistry Nikolay Aleksandrovich Figurovskiy (1983) wrote about their correspondence as follows:

Как явcтвует из дальнейшей переписки между Винклером и Менделеевым, в часности из письма от 5 марта 1886 г. и от 1 июня 1887 г. …, Винклер очень беспокоился, согласился ли Менделеев с предложенным названием элемента «германий» и не будет ли настаивать на своем названии «экасилиций». Винклер писал в своих письмах, среди прочего: ... Ваша любезная, очень обрадовавшая меня телеграмма, за которую приношу Вам свою нижайшую благодарноcть... я забыл Вам сказать, что предложение о том, что это (новый элемент ...) есть предсказанный Вами экасилиций, высказано не мною, а В. фон Рихтером в Бреславле, и он об этом сообщает в Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesselschaft. В письме ко мне почти одновременно с ним это же предложение высказал и Лотар Мейер в Тюбингене (As is evident from further correspondence between Winkler and Mendeleev, in particular from a letter dated March 5, 1886 and June 1, 1887..., Winkler was very worried if Mendeleev agreed with the proposed name for the element “germanium”, and whether he will not insist on its name “ekasilitsii”. Winkler wrote in his letters, among other things: ... Your kind telegram, which made me very happy, for which I bring you my lowest gratitude ...I forgot to tell you that the sentence that this (new element ...) is predicted by you ekasilitsii, expressed not by me, but V. von Richter in Breslau, and he reports this in Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesselschaft. In a letter to me, almost simultaneously with him, the same sentence was also expressed by [the German chemist] Lothar Meyer [1830-1895] in Tübingen) (pp. 127-128).

Mendeleev accepted the name of germanium for the element discoverd by Winkler. He informed him about it in a letter sent on April 21, 1886. Here is an excerpt (Makarenya, 1966) from Winkler's reply:

Милостивый государь! Вы, по всей вероятности, не представляете себе ту исключительную радость, которую Вы мне доставили Вашим любезным благожелательным письмом от 21 апреля. Содержание его и то, что Вы согласны с наименованием германия, очень меня успокоило, так как меня бы угнетало Ваше несогласие с выбором названия ... (Your Majesty! You, in all likelihood, do not imagine the exceptional joy that you brought me with your kind, benevolent letter of April 21st. Its content and the fact that you agree with the name germanium reassured me very much, since I would be depressed by your disagreement with the choice of the name …) (p. 56).

Mendeleev and V. v. Richter's letters to Winkler in German dated February 14/26 and February 25, 1866, respectively, were presented by Hanns C. A. Winkler in one of the chapters in the book entitled Clemens Winkler. Gedenkschrift zur 50. Wiederkehr seines Todestages (Winkler, 1954, pp. 38-39).

CONCLUSION

Clemens Winkler (1838-1904) was one of the prominent chemists of the second half of the XIX century. He received many scientific honours. Among them are a membership of the Academies of Sciences and Scientific Societies, as well as distinctions and decorations.

On December 9, 1878, he became member of the Kaiserlich Königlich Leopoldinisch-Carolingischen deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher (Imperial Royal Leopoldine-Carolingian German Academy of Natural Scientists) in Halle. One year later, he was elected a corresponding member of the Imperial Geological Institute in Vienna. He became a member of the Physical Association in Frankfurt a. Main (1887), the Society of Science in Leipzig (1890), the Swedish Society of Sciences in Stockholm (1892), the Dutch Society of Sciences in Harlem (1897).

In 1897, he became an honorary member of the Association of German Chemists. In 1900, he was elected a corresponding member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (Papperitz, 1904, p. 10).

He was the owner of the Komturkreuzes I. Klasse des Königlisch Sächsischer Albrechts-ordens (Kingly Saxon Albrecht-Order) and the Knight's Cross of the Merit I. Class (Papperitz, 1904, p. 10).

On January 20, 1896, the Verein zur Beförderung des Gewerbefleißes (Association for the Promotion of Industry) in Berlin conferred on him the golden Delbrück Medal “for merits, for development technical analysis of gases” (Anonymous, 1904, p. 900; Papperitz, 1904, p. 10; Prokop, 1954, p. 94).

Winkler's books appeared mainly in Germany. Only his textbook on technical gas analysis has been published in Great Britain and France. Some authors also wrote about his life and work. For instance, Erwin Papperitz wrote a 12-page article about him in 1904 (Papperitz, 1904). One year later, Winkler's obituary was written by Theodor Döring and published in the Zeitschrift für angewandte Chemie (Döring, 1905). In 1906, Otto Brunck wrote his obituary, which was published in the Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (Brunck, 1906). An article by Bernhard Sorms about him was published in 1990 in the History and Technology (Sorms, 1990). On the 100th anniversary of his death, two articles by Klaus Volke were published (Volke, 2004a; Volke, 2004b). Mike Haustein's 104-page biographical book about Winkler was published in 2004 in Frankfurt am Main (Haustein, 2004). Reviews of this book have been written by Walter Jansen (2005) and Klaus Möckel (2005). In 2012, Reiner Salzer wrote an article entitled Der Jungchemiker Clemens Winkler und das Blaufarbenwerk Niederpfannenstiel (The young chemist Clemens Winkler and the Blue Color Works in Niederpfannenstiel) (Salzer, 2012). In 2014, R. Klaus Müller wrote briefly about his life and work in one of the chapters of the book entitled Important Figures of Analytical Chemistry (Müller, 2014, pp. 70-71). Several authors have written articles about Winkler and the Germanium he discovered (Haustein, 2011a; Haustein, 2011b; Marshall & Marshall, 2001; Schwedt, 2009; Weinert, 2020).

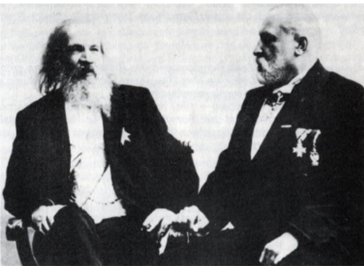

After Winkler, not only his papers, books and letters survived. In addition, several of his portraits and photos were produced. His portraits can also be found in the book by H. M. Smith (1949, p. 256) and in the book entitled Discovery of the Elements by the American chemist and historian of chemistry Mary Elvira Weeks (1892-1975) (Weeks, 1956, p. 683). One of his photograph is from the Edgar Fahs Smith Chemistry Collection (“Winkler, Clemens (1838”, n.d.). The photo of Winkler and Mendeleev (Figure 3) taken in March 1900 in Berlin can be found in the articles by Jansen (2005, p. 43), Makarenya (1966, p. 55) and Marshall & Marshall, 2001, p. 21). According to another source, the photo was taken six years earlier, during Mendeleev's stay in Freiberg in May 1894 (Winkler, 1954, p. 43).

Fig. 3 Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev and Clemens Winkler (left, and right respectively) (“Clemens Winkler zusammen”, 1900)

A Monument in honor of Winkler was erected in Freiberg, the town where he was born (“Clemens-Winkler-Denkmal”, 2013). In addition, an image of a commemorative plaque made in his honor can also be found in the literature. It was funded by the Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker (Society of German Chemists) and unveiled at the Old Chemical Institute of the Technischen Universität Bergakademie (Technical University Bergakademie) in Freiberg, on October 20, 2004, on the occasion of the 100th Anniversary of his death (“Historische Stätte der”, 2021). It has the following inscription:

HISTORICAL SITES / OF CHEMISTRY / IN THIS BUILDING LIVED, / RESEARCHED AND TAUGHT / CLEMENS ALEXANDER WINKLER / (1838-1904) / PROFESSOR AT THE ROYAL. - SAXON. / BERGAKADEMIE FROM 1873-1902 / CLEMENS WINKLER CARRIED OUT / PIONEERING WORK IN THE FIELDS OF / INORGANIC, ANALYSTS AND / TECHNICAL CHEMISTRY. THE FLUE GAS DESULPHURISATION PROCESS HE DEVELOPED MADE HIM / A PIONEER IN MODERN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION TECHNOLOGIES. ON FEBRUARY 6TH 1886 HE DISCOVERED / THE GERMANIUM HERE, WHEREBY THE / PROOF OF THE CORRECTNESS OF THE PERIODIC / TABLE OF THE ELEMENTS HAS BEEN ESTABLISHED. / THE RUSSIAN SCHOLAR DMITRI / MENDELEEV WAS A GUEST IN THIS HOUSE IN 1894. /UNVEILED ON OCTOBER 20, 2004 / IN THE 100TH YEAR OF CLEMENS WINKLER DEATH / GDCh SOCIETY OF GERMAN CHEMISTS (“Clemens Winkler, Gedenktafel”, 2008).

The name of this eminent German chemist is loudly heard among chemists in Germany. There is one award associated with his name. The Clemens-Winkler Medal is awarded by the Division of Analytical Chemistry of the German Chemical Society every two years. The award is accompanied by a certificate and a gold medal. The German analytical chemists receive this award for their “committed to the scientific development and the promotion and recognition of analytical chemistry deserved” (“Clemens-Winkler Medal”, 2021).