My SciELO

Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de Protección Vegetal

Print version ISSN 1010-2752On-line version ISSN 2224-4697

Rev. Protección Veg. vol.30 no.3 La Habana Sept.-Dec. 2015

COMUNICACIÓN CORTA

Effects of mineral, organic, and biological fertilization on the establishment of Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata (Kamyschko ex. Barron and Onions) Zare & Gams in a protected crop

Efecto de la fertilización mineral, orgánica y biológica sobre el establecimiento de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata (Kamyschko ex. Barron y Onions) Zare & Gams en cultivos protegidos

Nelson J. CharlesI, Jersys ArévaloII, Ailin Hernández DuquesneIII, Nelson J. Martín AlonsoIII, Leopoldo Hidalgo DíazII

ISeychelles Agricultural Agency, Republic of Seychelles. E-mail: nelcharless78@yahoo.com.

IINational Center for Animal and Plant Heath (CENSA), San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, CP 32700, Cuba.

IIIAgrarian University of Havana (UNAH), San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, CP 32 700, Cuba.

ABSTRACT

The objective of this research work was to evaluate the effect of applying different doses of mineral fertilization, organic fertilization (worm humus) or arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomus hoi-like) separately or in combination on the establishment of the strain IMI SD 187 of P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata. The experiment was carried out using the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) hybrid HA-3108 in a greenhouse at «Los 3 Picos» farm in Havana, Cuba. Colonization of the soil and roots by the selected strain was assessed in each treatment. The number of P. chlamydosporia colony forming units in soil and roots was directly related to the application of arbuscular micorrhizal fungi and worm humus according to the Principal Component analysis and the biplot graph used. A direct relationship between the mineral fertilization and P. chlamydosporia colonization of roots was found, while it was inverse respect the soil colonization. These results indicated that the nutritional treatments favored P. chlamydosporia (IMI SD 187) growth, with more significant effects when the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi were used combined with the worm humus.

Key words: Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, inorganic fertilization, nematophagous fungi, worm humus.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente trabajo fue evaluar el efecto de diferentes dosis de fertilización mineral, fertilización orgánica con humus de lombriz y hongos micorrízicos arbusculares (Glomus hoi-like), aplicados de manera separada o en combinación, sobre el establecimiento de la cepa IMI SD 187 de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata. El experimento se realizó en cultivo protegido en la Granja «Los 3 Picos», La Habana, Cuba. Se utilizó tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.), híbrido HA-3108, y se evaluó la colonización de la cepa seleccionada en el suelo y las raíces para cada tratamiento. El análisis de componentes principales, unido al gráfico de biplot, mostró una relación directa entre la utilización de micorriza y humus con el número de colonias de P. chlamydosporia en el suelo y la raíz. La fertilización mineral tuvo una relación directa con el número de colonias en la raíz e inversa con la colonización de este hongo en el suelo. Estos resultados indicaron que los tratamientos nutricionales probados favorecieron el crecimiento P. chlamydosporia (IMI SD 187) y el efecto combinado de micorriza y humus resultó ser el más significativo.

Palabras clave: Hongos Micorrízicos Arbusculares, fertilización inorgánica, Hongos nematófagos, humus de lombriz.

In Cuba, the integrated pest management is applied in the vegetable production under intensive systems, and the biological control agents (BCA) have great importance (1). In this type of technology, the root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) are the most important crop pests at the international and national scale (2, 3, 4).

The nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia (Goddard) Zare & Gams (former Verticillium chlamydosporium Goddard) is a facultative parasite of cyst and root knot nematode eggs. It is commonly present as a facultative saprophyte in a great diversity of soils of different agroecosystems worldwide (5). The effectiveness of P. chlamydosporia in reducing root knot nematodes has been demonstrated largely, and this effectiveness is increased when the fungus is applied in combination with other control measures such as the application of green manures, organic amendments or arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (6, 7, 8, 9).

The bionematicide KlamiC® is produced from the Cuban native strain IMI SD 187 of P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata and commercialized as effective for the management of Meloidogyne spp. in intensive production systems of vegetables (10). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of this microorganism in agricultural systems can be influenced by abiotic and biotic factors, like the biological composition of the soil and the competition with other microorganisms (11, 12). Therefore, evaluating the influence of the agricultural practices applied in the production system of vegetables is essential for the adoption of tactics and strategies favoring the establishment of this fungus in the rhizosphere.

The objective of this study was to determine the effect of different doses of mineral fertilization applied alone or in combination with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and worm humus on the establishment of P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata strain IMI SD 187 in soil and tomato roots under greenhouse cultivation.

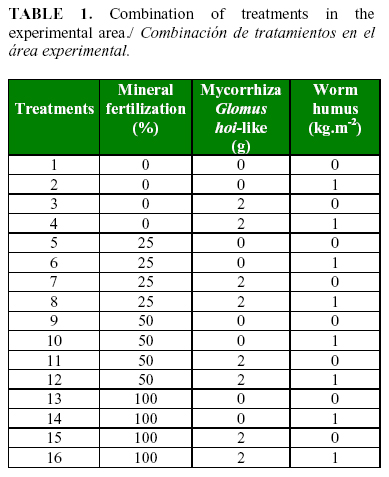

The work was carried out in a greenhouse at «Los 3 Picos» farm in Havana, Cuba. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings of the hybrid HA-3108 were used. Twenty five days after germination, the seedlings were transplanted to beds containing Ferralitic Yellow Gley soil (13). For the experimental work, a split-split plot randomized block design with four replications per treatment was used. A 3-way factorial arrangement was used to evaluate the application of different doses of mineral nutrients, worm humus and AMF, on the colonization of P. chlamydosporia in the soil and tomato roots. Table 1 shows the combination of the treatments in the experimental area.

The doses of mineral fertilizers (0, 25, 50 or 100%.) were applied to the main plots through the irrigation water. According to Casanova et al. (14), the fertilizers used in the fertigation system were: magnesium nitrate (11-0-0-0-15); calcium nitrate (15.5-0-0-26), phosphoric acid (85%), potassium nitrate (12-0-45), and ammonium nitrate (34-0-0).g. Two treatments of worm humus (with 1 kg.m-2 or none) were used in the sub- plots. The sub-sub-plots were or not inoculated with the AMF. A certified inoculum of Glomus hoi-like fungi of an ecological commercial product (Ecomic®) from the National Institute of Agricultural Science (INCA, Cuba) was used to inoculate the AMF, which were applied by coating the seeds with a volume of product corresponding to 10% of the seed weight (15).

Three days before transplanting the seedlings, KlamiC® (a.i., P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata) was applied to all the plots at a rate of 25 g.m-2 of soil (16). An inundative application of the fungus was carried out by spraying 1 kg of the product over each bed (40 m2 area) around the roots once a month during three consecutive months. The experiment was established and carried out for five months (from December 2009 to May 2010), and a second repetition was done one year after (from December 2010 to May 2011). After each period, the colonization of the substrate and tomato roots by P. chlamydosporia was determined by counting the number of colony forming units (CFU) according to Kerry and Bourne (17).

The data obtained were log(x+1) transformed. Treatment behavior regarding P. chlamydosporia growth and the correlation between the different variables were evaluated by using a principal component analysis and a biplot graph using InfoStat version 1.1 (18).

Root and soil colonization by P. chlamydosporia was in the range 3.33 x 102-3.53 x 103 CFU.g-1 and 9.83x102-1.56x104 CFU.g-1, respectively, at the end of the experiment,t with no significant differences between the two years (p>0,05). The analysis of principal components showed an 87 % correlation. Two principal components could explain more than 76 % of the variance (Table 2). The first principal component (CP1) showed a direct relationship between the use of mycorrhiza or worm humus and the number of colonies formed by P. chlamydosporia in the soil (CFUs) and roots (CFUr), which indicated that these treatments promoted the growth of the fungus. Fertigation, the second component (CP2), showed a direct relationship with the root colonization, but it was inverse with the quantity of CFUs in soil (Table 2).

The biplot graph (Figure 1) revealed that the best treatments with the highest CFUs and CFUr were 8, 12 and 16, where the application of mycorrhiza and humus in combination with the fertigation at the doses of 25, 50 and 100 % respectively; according to these data, the fertigation did not affect P. chlamydosporia establishment, even at a dose of 100 %. Treatments 5, 9, and 13 (with no application of mycorrhiza or worm humus) showed lower P. chlamydosporia growth in the soil and roots, and they were placed into the same group of the control treatment (treatment 1). Treatments with application of mycorrhiza or worm humus separately presented an intermediate growth of the nematophagous fungus.

The establishment of P. chlamydosporia in the rhizosphere is essential for survival of this fungus in absence of the nematode host, as well as for nematode control (19). Previous studies have demonstrated that proliferation of P. chlamydosporia is more abundant in organic than mineral soils (20). The present work indicated that nutritional treatments favored the growth of P. chlamydosporia, with a more remarkable effect of the combined use of mycorrhiza and worm humus.

The application of Glomus hoi-like favored P. chlamydosporia growth in soil and roots. Previous studies by Puertas et al. (21) demonstrated the compatibility of P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata (IMI SD 187) and AMF (Glomus clarum) and the possibility of combining them in nematode management. On the other hand, the inoculation of Glomus mosseae and P. chlamydosporia limited the development and effectiveness of the nematophagous fungus in roots, probably because of the competition between both microorganisms in the rhizosphere (7). Studies by Siddiqui and Akhtar (6) revealed a synergetic effect between P. chlamydosporia and the AMF Glomus intraradices on the reduction of galling and multiplication of M. incognita and caused a significant increase of tomato growth. Furthermore, the strain IMI SD 187 was recently shown to be plant endophytic (22); this capability could give this fungus a potential effect on plant growth and health (23).

The studies by Theunissen et al. (24) proved that the application of worm humus stimulated the increase of microorganisms taking part in its decomposition, promoted the synthesis of phenolic compounds that improve the plant quality, and acted as a deterrent against pests and diseases. Puertas and Hidalgo-Díaz (9) observed that P. chlamydosporia growth was not limited by worm humus, a result that agrees with the results obtained in this work.

The mineral fertilization did not affect P. chlamydosporia establishment, even in the treatments where 100 % doses were applied. Mineral fertilizer per se did not stimulate the saprophytic development of the fungus, but it was related to root colonization by P. chlamydosporia. This could be by the fungus feeding on root exudations. Fertigation has been reported to have a more direct influence on plant growth and changes in root exudations (25).

However, the indiscriminate application of mineral fertilizers induces variations in the physical condition of the soil, like changes in the pH and not optimal cationic relationships, that result in unfavorable physical properties of the soil and thus contributes to the intensification of erosion and pollution of the environment (26). These effects influence adversely on the microbiota of the agroecosystem. A way to avoid the deterioration of soil fertility in intensive farming is combining the use of adequate quantities of mineral fertilizers with products of microbial origin (27). Some studies demonstrate the beneficial effects of the symbiotic association between the AMF and plants. The combined application of AMF and low doses of mineral fertilizers increase the effectiveness of the mycorrhizal symbiosis, and an optimum dose of fertilizers lower than the recommended to obtain similar yields is achieved (28).

The results obtained by Charles and Martin (29) showed a synergetic effect on the production of tomato under a protected cultivation when they combined the application of EcomiC® and worm humus with a dose of 50 % mineral fertilization. In this sense, it was interesting to note that combined application of mycorrhiza and worm humus contributed to a better establishment of the strain IMI SD 187 of P. chlamydosporia var. catenulata at this intermediate level of mineral fertilization in both years. Therefore, it is feasible to integrate KlamiC® with these management measures for the tomato crop in intensive production systems, and it is recommended the conduction of further research emphasizing their common benefits in the growth and development of plants and the protection against populations of root-knot nematodes.

REFERENCES

1. Ceiro W. Evaluación de una alternativa de manejo sostenible para Meloidogyne spp., en cultivo del tomate (Solanum lycopersicum M.). Rev Protección Veg. 2010;25(3):197.

2. Gómez L. Diagnóstico de nematodos agalleros y prácticas agronómicas para el manejo de Meloidogyne incognita en la Producción Protegida de Hortalizas. Tesis para optar por el Grado Científico de Doctor en Ciencias Agrícolas. Universidad Agraria de La Habana- Centro Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria. 2007; 100p.

3. Escudero N, López-Llorca LV. Effects on plant growth and root-knot nematode infection of an endophytic GFP transformant of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia. Symbiosis. DOI: 10.1007/s13199-012-0173-3. 2012.

4. Manzanilla-López R, Esteves I, Finetti-Sialer M, Hirsch P, Ward E, Devonshire J, et al. Pochonia chlamydosporia: Advances and challenges to improve its performance as a biological control agent of sedentary endo-parasitic nematodes. Journal of Nematology. 2013;45(1):1-7.

5. Gams W, Zare R. A revision of Verticillium section Prostrata. III. Generic classification. Nova Hedwigia. 2001;73(3-4):329-337.

6. Siddiqui ZA, Akhtar MS. Synergistic effects of antagonistic fungi and plant growth promoting rhizobacterium, an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, or composted cow manure on populations of Meloidogyne incognita and growth of tomato. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 2008;18(3):279-290.

7. Hernández MA. Interacción de Glomus mosseae - Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata y Meloidogyne incognita en tomate (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Tesis en opción al grado académico de Maestro en Ciencias en Nutrición de las plantas y biofertilizantes. La Habana. 2009: 89 pp.

8. Arévalo J, Silva SD, Carneiro MDG, Lopes RB, Carneiro RMDG, Tigano MS, et al. Efecto de la presencia de abono orgánico sobre la actividad de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata (Kamyschko ex Barron y Onions) Zare y Gams frente a Meloidogyne enterolobii Yang y Eisenback. Rev Protección Veg. 2012;27(3):167-173.

9. Puertas A, Hidalgo-Díaz L. Efecto de diferentes abonos orgánicos sobre el establecimiento de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata en el sustrato y la rizosfera de plantas de tomate. Rev Protección Veg. 2009;24(3):162-165.

10.Hidalgo-Díaz L. Investigación, desarrollo e innovación de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata como agente microbiano para el control de nematodos formadores de agallas. Rev Protección Veg. 2013;28(3):238.

11.Monfort E, Lopez-Lloca L, Jansson H, Salinas J. In vitro soil receptivity assays to egg-parasitic nematophagous fungi. Mycol Progress. 2006;5:18-23.

12.Atkins S, Peteira B, Clark I, Kerry B, Hirsch P. Use of real-time quantitative PCR to investigate root and gall colonization by co-inoculated isolates of the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia. Annals of Applied Biology. 2009;155:43-152.

13.Instituto de Suelos. Academia de Ciencias de Cuba. Génesis y Clasificación de los suelos de Cuba. Cuba. 1999: 77-78.

14.Casanova A, Gómez O, Pupo FR, Hernández M, Chailloux M, Depestre T, et al. MINAG-Viceministerio de Cultivos Varios. Instituto de Investigaciones Hortícolas «Liliana Dimitrova». Manual para la producción Protegida de Hortalizas. La Habana, Cuba. 2007: 80.

15.Fernández F, Vanega LF, Noval B, Rivera R. Producto inoculante micorrizógeno. Oficina Nacional de Propiedad Industrial. No. 22641. Cuba. 2000.

16.Hernández MA, Hidalgo L. KlamiC®: Bionematicida agrícola producido a partir del hongo Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata. Rev Protección Veg. 2008;23(2):131-134.

17.Kerry BR, Bourne JM. A Manual for Research on Verticillium chlamydosporium, a Potential Biological Control Agent for Root-Knot Nematodes. IOBC/WPRS, University of Gent; 2002: 84 pp. ISBN 92-9067-138-2.

18.Miranda I. Centro Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria (CENSA). Estadística aplicada a la Sanidad Vegetal. Cuba, 2011: 17 pp. ISBN 978-959-7125-44-0.

19.Bourne JM, Kerry BR, de Leij FAAM. The importance of the host plant on the interaction between root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) and the nemathophagous fungus, Verticillium chlamydosporium (Goddard). Biocontrol Sci and Technol. 1996;6:539-548.

20.Kerry BR. Fungi as biological control agents for plant parasitic nematodes. In: Whipps JM, Lumsden RD (Eds.). Biotechnology of fungi improving plant. 1989;153-170.

21.Puertas A, de la Noval B, Martínez B, Miranda I, Fernández F, Hidalgo L. Interacción de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata con Rhizobium sp., Trichoderma harzianum y Glomus clarum en el control de Meloidogyne incognita. Rev Protección Veg. 2006;21(2):80-89.

22.Arévalo J. Avances en la caracterización de la cepa IMI SD 187 de Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata (Kamyschko ex. Barron and Onions) Zare & Gams y mejoras productivas de bionometicida Klamic®. Rev Protección Veg. 2013;8(1):0.

23.Maciá-Vicente JG, Jansson H-B, Talbot NJ. Real-time PCR quantification and live-cell imaging of endophytic colonization of barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots by Fusarium equisetiand Pochonia chlamydosporia. New Phytol. 2009;182:213-228.

24.Theunissen J, Ndakidemi P, Laubscher C. Potential of vermicompost produced from plant waste on the growth and nutrient status in vegetable production. International Journal of the Physical Sciences. 2010;5(13):1964-1973.

25.Spann TM, Schumann AW. Mineral nutrition contributes to plant disease and pest resistance. University of Florida IFAS Extension. Available in: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs1181. Consulted: 18/02/2014.

26.Orellana RM, Hernández O, Quintero PL. Consecuencias de la aplicación excesiva de fertilizantes minerales en el estado físico de los suelos. In: Summary of the II Organic Agriculture National Meeting. Havana, Cuba. 1995, 13.

27.Martinez R. El uso de biofertilizantes. Curso de Agricultura Orgánica. ICA. La Habana. 1994.

28.Martín G, Rivera R, Pérez A. Efecto de canavalia, inoculación micorrízica y dosis de fertilizante nitrogenado en el cultivo del maíz. Cultivos Tropicales versión ISSN 0258-5936. 2013:4(34).

29.Charles NJ, Martin NJ. Manejo de Hongos Micorrizicos Arbusculares (HMA) y humus de lombriz en el cultivo del tomate Solanum lycopercum L. bajo condiciones de cultivos protegidos. XVII International Scientific Congress Memories. National Institute of Agricultural Sciences. Mayabeque, Cuba. 2010; November 22-26. Available in: http://ediciones.inca.edu.cu/files/congresos/2010/CDMemorias/memorias/ponencias/talleres/CMM/ra/CMM-P.28.pdf. Consulted: 17/02/2014.

Recibido: 6-7-2015.

Aceptado: 3-11-2015.