My SciELO

Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Mendive. Revista de Educación

On-line version ISSN 1815-7696

Rev. Mendive vol.22 no.1 Pinar del Río Jan.-Mar. 2024 Epub Mar 30, 2024

Original article

Women from Pinar del Río in musical pedagogy during the first half of the 20th century

1Universidad de Pinar del Río "Hermanos Saíz Montes de Oca", Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Departamento de Historia, Pinar del Río, Cuba.

In this article, the authors addressed the insufficient academic treatment offered to the participation of women from Pinar del Río in musical pedagogy. Therefore, it proposes a study on the participation of women from Pinar del Río in musical pedagogy during the first half of the 20th century, from a socio-historical, cultural and gender perspective. Various theoretical methods were used such as dialectical, historical-logical, ethnographic, as well as analysis and synthesis. Within the empirical methods, they apply the interview and the documentary analysis, in addition to the publicist sources of the investigated historical period, together with the oral sources. As a result, it shows the contribution of women from Pinar del Río to the teaching of music with solid contributions to didactics, from their work in the academies, in a context characterized by a rigid social organization, in which professionalism was seriously damaged by erroneous approaches. Of gender, by rejecting free female public expression, minimizing their training capacities and the knowledge they transmitted. Also damaged by the effects of Pinar del Río's function of economic, political and social subordination, as a historical region to the nearby capital of Havana. Therefore, to make visible the contributions made by Pinar del Río women in this sense, to contribute to dignifying their image in the field of artistic culture, education and pedagogy from Pinar del Río and Cuba, as well as to strengthen the identity and the local intangible cultural heritage and nationals.

Key words: music teaching; woman from Pinar del Río; musical pedagogy

Introduction

The history of artistic creation has been the subject of study by many authors during different periods. The studies carried out on this topic in the world have a marked difference in terms of the female presence compared to the male one. In general, the participation of women in these analyzes is vetoed, which has as its starting point the discrimination that, through centuries, the so-called weaker sex has suffered in different societies. For academics like Torrent (2012), this constitutes a form of violence by minimizing and silencing their findings, in this case from the creative sphere.

Scientific research on the subject allows us to verify that in the course of Historically, gender bias has mediated scientific discourses of all kinds. Her presence has manifested itself in a variety of ways, but always contributing to showing a unique idea of women, constructed by androcentric societies .

The history of music does not escape the effects of this sexual segregation. The teaching of music is one of the main fields of performance explored by women, as teaching is one of the professions approved and preferred by the patriarchal assumptions of different societies throughout the development of Humanity, with a transcendence to contemporaneity. This is recognized by Soler when he points out that "...musical teaching has become a fundamentally feminine practice, however, the leaders in this sector are men...activities that require leadership usually have a greater male presence" (2020, pp. 111- 112)

Research on music teaching is characterized by showing the historical role that conservatories have played, the prominent participation of women in these institutions, and their imprint on the cultural identity dynamics, fundamentally during the 20th century, which can be evidenced in the studies done by Hernández, (2017); García, (2014). This is conditioned by the contribution of these institutions to the development of the training processes of the professional musician.

In Cuba, important studies have been carried out on female participation in music teaching during the first half of the 20th century, where the recovery of names and contributions of historically silenced women is mostly seen, who have had the work of Valdés as an important reference. (2005). Research Rodríguez and Barceló (2009) addresses the ideas and work of men and women who mark, together with prominent institutions, the breaking of precepts that trigger the instruction of music, from the end of the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. Along similar lines, Conde and Herrera (2017) study Cuban pedagogical thought in the first twenty years of this century, where they show the sociocultural changes of a time in which women contribute to the construction of the nation through education.

Also characteristic of these analyzes not only in Cuba, but internationally, is the recognition of the presence of gender bias in Musical Education (Botella, 2018) and the need to modify practices in this Teaching process. (Lugo, 2020).

Rosales et al. (2017), particularly recognizes how Cuban society declares itself in favor of equality between the sexes and facilitates its social exercise; However, the invisibility of feminine identities and practices in teaching materials and the teaching-learning process in general continues to be a reality.

These arguments are in line with the theoretical foundation that Soler (2018) maintains when classifying gender studies in Musical Education includes the following: compensatory research, which includes works that have recovered the names of a multitude of women up to then unknown; historical rereading as a form of deconstruction of androcentric discourse; research on the teaching-learning process that marks the critical forms of new styles in teaching practice in accordance with the lines of work of Emancipatory Pedagogy; the assignment of gender roles and the construction of identities in an equitable manner, where it is also intended to provide an explanation for the traditional absence of the male sex in certain musical facets, placing emphasis on how these develop in certain musical fields that have been traditionally feminine.

With all this, in the opinion of Alvarado and Trejo (2022), it is tributed to the scope of a musical pedagogy committed to human rights, which safeguards human dignity above all. The studies carried out, interchangeably from the Social Sciences by Carrión and Parrado, (2019); Díaz, (2018); González, (2002); Morales et al. (2017), have been fundamentally directed at the need to incorporate the gender perspective, based on the assumption that any science that tries to explain social reality must introduce into its analysis the differences in behaviors, experiences, opportunities and roles between women and men.

The gender approach, in historical-pedagogical research on music in Cuba, without yet being a systematic perspective, has been growing gradually since the 1990s. It is enhanced by the emergence of different multidisciplinary groups that discuss gender issues. and demonstrate the need to reflect on the unequal position occupied by women and men.

The province, from the work carried out by the Cuban Pedagogues Branch, has research on figures from the territory who made contributions to the Cuban teaching profession, however, those referring to the teaching of music are meager; The educational work of Rosa Delgado de Pasos, composer of the Anthem of Pinar del Río, has been addressed to a greater extent.

The above indicates that studies about Pinar del Río women in musical pedagogy, seen with a gender approach, have not been investigated in depth; there is an absence of information that deserves the carrying out of various studies that contribute to the knowledge and recognition of the contributions made by them, fundamentally in the first half of the 20th century.

In general, what is scarcely written on the topic investigated is not only dispersed, but the approaches of the studies have been fragmentary, perhaps because a documentary base has not been created in this sense that allows generalizing trends and guidelines on the incidence. of Pinar del Río women in music teaching at this stage.

An in-depth study on this topic allows us to witness the deployment of women in the musical life of Pinar del Río, which can be a starting point to create new perspectives and other investigations that do not remain only in the musicological field, but also intervene in the Social Sciences in order to enrich current studies on women in terms of social roles and spaces, as well as the need to reflect on the unequal position that women and men occupy based on the social construction that is built on the biological fact of be of one sex or the other.

Furthermore, it makes it possible to analyze that women in Pinar del Río society of this period suffer discrimination and non-participation in cultural life more rigorously than in other regions, such as Havana, a paradigm close to the Pinar del Río region. What responds to regionalism and rigid patterns, inherited from the colonial era, in a territory that, due to its economic, political and social conditions, historically fulfilled the function of subordination to the capital of the country, dragging this condition until the first half. of the 20th century. In this sense, this historic region west of Havana becomes an exceptional space, with characteristics that are impossible to find in any other region of the country and that tends to resist many of the discrete changes that are coming into view on the national panorama.

The study carried out contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of musical pedagogy in the territory. With this, in addition, tribute is paid to all the women who, although they did not transcend the time in which they lived, did leave an indelible mark from the teaching of music, by showing the sociocultural changes of a time in which women contribute to the construction of nationality and the Cuban nation through education, which is why it is part of the Pinar del Río identity.

This work also serves to promote the compilation of a historical sample of women whose work is part of the intangible cultural heritage of the territory, a fragile heritage, whose conservation and safeguarding is urgent, as well as the need to incorporate it, as a strategic element to the policies of local development.

Based on these considerations, the intention is to analyze the presence of Pinar del Río women in musical pedagogy during the first half of the 20th century, from a socio-historical, cultural and gender perspective. What would help legitimize the vision that is held about the performance of women in the development of local musical culture and make visible their role as an important agent of social development during this period.

Materials and methods

To carry out this research, the authors carried out the application of methods and techniques adjusted to the objective. The theoretical methods were based on the historical-logical, the inductive-deductive and the analysis-synthesis, assisted by the method of compilation and critical analysis of the sources, in the process of selection and interpretation of the information, with the intention of specifying the nature, degree of reliability, class and institutional interests and the real significance of the sources, which made possible the application of the concepts of musical pedagogy, gender approach and intangible cultural heritage, as well as the limitations and successes in their formulation, with in order to establish the presence of Pinar del Río women in musical pedagogy during the first half of the 20th century.

Furthermore, the authors provide useful concepts for research such as pedagogical musical thinking, which is materialized from the actions of the musicians who teach in the search for solutions to technical and expressive problems that must be achieved with the students, through open and flexible experimentation, in which various techniques and methodologies are applied, derived from musical practice, and from which the pedagogical act emanates.

The research privileged qualitative methodology, since it was essential to discover aspects related to feelings, attitudes, beliefs, motives and behaviors. For this reason, the ethnographic method was used, pursuing the description or analytical reconstruction of the presence of Pinar del Río women in music teaching, their actions and representation in society during this stage. The analysis of documents, especially the review of advertising sources, was of vital importance in obtaining the results, as there were no previous studies that had emphasized the topic investigated.

It was also of singular importance to use oral history, from the interview method, since it allowed the rescue of the lives, the episodes or situations in which the testimonies participated, which provided not only information about some event, but also It also made it possible to take a personal look at those events and themselves. Empirical and symbolic data greatly helped to recover the memory of female musical education in the first half of the 20th century.

The interviews were applied in a structured and unstructured way, aimed at women and men of different ages, races and social background, who have maintained or maintain an active participation in Pinar del Río musical culture and in teaching specifically, to achieve different points. of view in relation to the topic, whose processing through statistical programs made possible the interpretation of the results obtained, thus achieving a more complete vision of the object of study.

A non-probabilistic or directed sample was used, since the choice of subjects depended on the criteria as researchers, which was based on the selection of those who, due to their professional and ethical qualities, their independence of judgment, personal experience, creativity, the self-critical level and the academic or scientific degree, have become distinguished makers of the musical pedagogical heritage of Pinar del Río.

The interviews were carried out individually and had as their guiding thread the search for the perception of the significance of the contribution of women, who in the province ventured into teaching music at this stage, as well as their own experiences. Observation was also applied regarding the manifestations of women, who in the investigated context developed meritorious work in teaching music.

Results

Teaching was one of the occupations carried out by women from the first years of the 20th century, which is why it had a determining role in the development of musical education of the time. During the first half of the 20th century, various music academies attached to the National Conservatories were created in the province.

Argeliers León Music Documentation and Information Center , in the File Academies and Conservatories, it was found that these academies, the vast majority were directed by women, reflecting in their generalities, the name of the Academy , the Conservatory to which it belonged, the musical instrument that was studied, the year of foundation and its location in the territory, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1 - Academies in the city of Pinar del Río directed by women in the first half of the 20th century.

| Academy and Year of foundation | Conservatory | Instrument | Location | Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maria del Pilar | Eduardo Peyrellade | Piano | Calle Rosario, corner Yagruma (in its beginnings) and later: Calle Maceo No. 92. | Firstly, by María del Pilar Gandarilla and then Consuelo Azcuy Menéndez |

| María Teresa Fernández de Alea | Orbon | Piano | Volcano Street / Alameda and Yagruma | Maria Matilde Alea |

| Maria Josefa | González Molina Conservatory directed by Joaquín Molina Ramos | Piano | Máximo Gómez No.56 | Maria Josefa Garay |

| Amparo Saiz | Maximo Gomez 34 | |||

| Estrella It was founded in 1926. | Santa Ana Academy of Havana, directed by María Arrate | Piano | Barracks Street No.3 / Yagruma and Retiro. | Zoila Estrella Almirall. |

| La Milagrosa was founded in 1944. | Piano and Violin | Recreo Street No.4 /Mariana Grajales and Delicias. | Aida Hermida. | |

| Rosita Delgado Caraballo | Fishermann . | Piano | Isabel Rubio Street, No.4. | |

| Mozart | Orbon . | Piano | Cavada/ Martí and Máximo Gómez. | Delia María García Figarall . |

| Marthica Quintero Cuervo Existence in 1935 | ||||

| Santa Cecilia Ventura A. LabiadaThis academy was founded in 1944. | International Conservatory of Music | Piano | Máximo Gómez Street/ Colón and Recreo. | |

| Fair Regal. | International Conservatory of Music. | Piano and Ballet | Martí Street / Nueva and Rosario Streets | |

| Candy Valle by Fernández Riquier | Raventós | Piano | ||

| Marcia Álvarez González Founded in 1954 | International Conservatory of Music | Piano and Ballet | Martí Street No.145. |

Source: Music Documentation and Information Center " Argeliers León", in the Academies and Conservatories File.

Among other data of interest that complement their history, in many of these academies, although the use of the piano is explicitly stated in the sources, there were other instruments that were taught in these institutions, as is the case of the María Josefa academy, where there is a high level of probability that the violin was also taught, since the Director of the Conservatory Joaquín Molina Ramos, founder and first vice president of the Havana Symphony Orchestra, was a violin pedagogue and the María Josefa Garay Academy was attached to his Conservatory.

These academies are also incorporated indiscriminately into various conservatories in Havana, as their quality and student body increased, such as the Estrella Academy, which was incorporated into the Santa Ana Academy in Havana, directed by María Arrate and later appears as incorporated into the Carlos Alfredo Peyrellade Conservatory, most prestigious in the field.

There were some academies that, although no data appears in relation to their existence in the period studied, there is evidence of their presence in the territory through the local press, such as the Marthica Quintero Cuervo academy, which appears registered in an advertisement in the newspaper El Heraldo Pinareño of May 9, 1935, which refers to the celebration in this institution of a magnificent concert in which a large number of people participated.

Other academies changed their location several times, making it difficult to establish their presence in the territory, such as the Justa Regal Academy, belonging to the International Conservatory of Music, which was initially located on Martí Street between Calle Nueva and Rosario and later on Calle Martí, Malecón No. 162 between Calle Nueva and Cavada, it is also said that it was located for a time on Calle Maceo between Galiano and San Juan.

Many of these teachers from the music academies of the city of Pinar del Río taught classes in some municipalities of the province, where these institutions did not exist, such as Delia María García Figarall, director of the Mozart Academy, who taught music in Guane and Viñales, as well as on other occasions, sent teachers from their academy to these functions. Although in the studies carried out in the period under study, it was possible to verify the existence of these academies, directed by women in the majority of the municipalities of the province, as exemplified in Table 2 .

Table 2 - Sample of Music Academies existing in the province of Pinar del Río during the first half of the 20th century.

| Academy | Teachers | Municipality | Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juanita Alfonso | Juanita Alfonso | La Palm | Piano |

| Clara Elena Then | Clara Elena Then Luzina | La Palm | Piano |

| María Cristina Gelat | María Cristina Gelat | La Palm | Piano |

| Zoila Rosa del Pino | Dolores Pruneda and Lolina Rueda | Consolación del Sur | Piano |

| Olga Paragon | Olga Paragon | San Juan and Martínez | Piano |

| Rebeca Mármol Vales | Rebeca Mármol Valdés | San Luis | Piano |

| Garcia Caturla | Gertrudis Moa González | San Luis | Piano |

| Romelia Barefoot | Romelia Barefoot | Bahía Honda | Piano |

| Isora Gutierrez | Isora Gutierrez | San Cristobal | Piano |

| Nora Torres | Nora Torres | San Cristobal | Piano |

Source: Argeliers León Music Documentation and Information Center. File Academies and Conservatories.

Among the women who were in charge of the direction of said Academies are the names of María del Pilar Gandarilla, Consuelo Azcuy Menéndez, María Teresa Fernández de Alea, María Matilde Alea, María Josefa Garay, Zoila Estrella Almirall, Rosita Delgado Caraballo, Delia María García Figarall , Marthica Quintero Cuervo, Ventura A. Labiada, Justa Regal, Candy Valle de Fernández Riquier , Amparo Saíz and Marcia Álvarez González.

Among the Havana conservatories that had academies in the province, the International Conservatory of Music, the Orbón, the Raventós, the Peyrellade, the Fishermann and the González Molina were among the most representative. Many of these conservatories were attached to the Ministry of Education, so their diplomas had official validity, allowing graduates to work in public schools. So insertion into academies constituted a future source of work for women.

However, the majority of these women dedicated to musical teaching were victims of class discrimination, as they were forced to establish private academies, because after demonstrating sufficient talent by passing the corresponding exams and obtaining first places in competitive positions, these music teacher positions were denied to her in public schools, which could be verified in interviews with directors and music teachers from Pinar del Río. An example of these injustices is what happened to the eminent musical pedagogue Marcia Álvarez González, who was denied a place at the José Martí school, with said place being granted, by Presidential Decree, to Concepción Menéndez, daughter of Senator Pedro Menéndez of San Juan y Martinez.

There were regulations for the academies incorporated into the Conservatories of Havana, assuring them that they would be attended to and that once or twice a year the director would come personally or the person designated by them to examine the academy's students. Each of these Conservatories had its Study Plan.

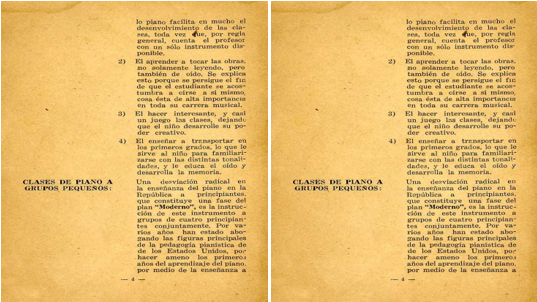

Source: Argeliers León Music Documentation and Information Center. File Academies and Conservatories.

Source: Argeliers León Music Documentation and Information Center. File Academies and Conservatories.Fig. 1 - Plan belonging to the International Conservatory.

In the press of the time it was very common to find in the social chronicles, the disclosure of the exam presentations of these academies, where the musical abilities and aptitudes of the contestants were not highlighted, but rather the feminine physical attributes. (See Figure 1). This discrimination to which Pinar del Río women were subjected was corroborated in the review carried out by the newspaper El Heraldo Pinareño in 1934, such as the one published about the beautiful and gentle Miss Rosita Delgado, who represented the city of Pinar del Río, at the piano exams held at the Fishermann Conservatory Branch. The exams were quite an event in the city and generally ended with a concert at the Riesgo theaters, now the Pedro Zaidén cinema, the Aída, now the Praga cinema, as well as at the theater of the local radio station CMAB.

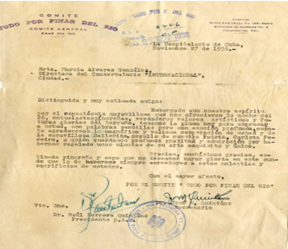

The academies frequently organized concerts and various activities that contributed significantly to the development of the territory's musical culture. This is illustrated through an official notification issued by the All for Pinar del Río Committee to the academy director, Marcia Álvarez González, where she is thanked for the show presented. (Figure 2) These institutions, as we have explained, were mainly piano-based, but there were some such as Aida Hermida, where other instruments were studied in addition to the piano, in this case the violin.

Source: Personal document of Marcia Álvarez González.

Source: Personal document of Marcia Álvarez González.Fig. 2 - Official notification issued by the All for Pinar del Río Committee to Marcia Álvarez González, director of the International Conservatory of Music.

During the 1950s there were only two ballet and piano academies in the city of Pinar del Río, Marcia Álvarez and Justa Regal. Argentine Carlota Pereyra, prima ballerina at Alicia Alonso's academy and professor at the International Conservatory of Music, was Marcia's ballet teacher and traveled to the province twice a week. In a communication given by María Jones de Castro, director of the International Conservatory, the inauguration of the Ballet Department at this Academy is reported. Likewise, with the same frequency, José Pared, first dancer at the Alicia academy, attended the Justa academy.

It is important to note that Marcia González's academy marked a milestone in the teaching of music in Pinar del Río with the establishment of a musical Kindergarten for preschool children (Figure 3), having as the only similar one in the country, that of the International Conservatory of La Havana.

Source: Personal collection of Marcia Álvarez González.

Source: Personal collection of Marcia Álvarez González.Fig. 3 - Musical kindergarten for preschool children established by Marcia Álvarez González, at the International Conservatory of Music.

The methodology used to teach how to read music to children who did not know how to read and write was very innovative. As an example, we have the teaching medium created by the aforementioned pedagogue called the musical table. It was a square table with a green glue surface imitating a billiard table, where staves are presented, that of the treble clef and that of the fa clef, with the notes of each scale placed irregularly, where each one has a sunken surface. to place a chinata on each note. On each side of the table there is a painted piano keyboard and it also has a recess in each key to place the chinata. The game consisted of each child individually throwing a chinata placed on the green surface with their thumb and middle finger, trying to collide with the balls that are on the pentagrams. They had to recognize the name of those notes that for them are the children of Mama Sol and Papa Fa and in a second stage know how to place them in the corresponding box on the keyboard.

The existence of various academies gave rise to competition between them, however, the spirit of cooperation that always existed between them stands out among their teachers. An example that illustrates this cooperation is that when Ventura Labiada's sister, director of the Santa Cecilia Academy, fell ill with schizophrenia, Delia García Figarall, director of the Mozart Academy, lent her premises with chairs, tables and a piano for the teaching of the classes. classes to the students of the Ventura academy. In general, these academies contributed to raising the cultural level of the population, and specifically to forming a musical culture in it. The concerts and activities that were organized with their own resources constitute proof of the spirit of consecration that prevailed in them.

Reference was made primarily to women who ran academies in the city of Pinar del Río, but there were many who throughout the province dedicated themselves to teaching music, either from official academies or from their homes. As were Zoila Rubalcaba, Lolina Rueda, Amalia Millares, Flora Prieto and Zoraida Fernández. Likewise, it was coincidental that some of the women dedicated to musical teaching also developed contributions to composition. These are the cases of Rosa Delgado Caraballo, author of the Hymn of Pinar del Río, Humbelina Díaz Bruno, María Matilde Alea, who can also be included as a concert pianist, and Celedonia Ismail Hernández.

It is worth noting that these teachers became bastions of Pinar del Río education and culture by successfully and creatively conducting music teaching in the province, which today is reversed through the existence of excellent professionals, not only in the field of teaching, but in the musical field entirely, managing to cross the borders of the province and the country.

Discussion

The participation of Pinar del Río women in music teaching during the period analyzed not only recovered names and showed the contributions of many of the women who stood out in this field, but also allowed establishing and interpreting their interaction with a society that opposed serious obstacles to cultural development in general, especially in Pinar del Río, whose condition as a province made it more difficult than in the country's capital for women to function beyond the limits established by the family and social conventions. All of the above coincides with the criteria of Barceló and Rodríguez (2009).

Much was reported in the local press of Pinar del Río at the beginning of the 20th century, mainly in articles from social chronicles, about the sweetened role of women in musical culture, fundamentally in concert genres, as professors in academies that linked music and dance, mostly related to the piano and other string instruments, without exceeding the limits of ballroom dances, typical of the time (Morales et al., 2017). In other cases, his participation in gatherings or other meetings where he performed his repertoire, generally European with piano accompaniment, was reviewed.

It is striking how the praise of the female image appears explicitly in the publicity notes, rather than her artistic merit and creative talent. (León de la Paz et al., 2019). It was common to find in the press of the aforementioned period, when reference is made to the presence of women in the musical harmonization of the dances and parties of the Instruction and Recreation Societies, finding expressions such as very beautiful girls, offering the charm of their delicious talk and the incentive of their luminous looks, full of softness and sweetness. Women were represented in the advertising media of the time as a signifier in the context of male activities.

The lack of social recognition, specifically towards those women who worked in the cultural field, was published without scruple in Revista Dominicales of the time, (Esquenazi et al., 2017), a criterion that was evidenced in the scenario investigated since they were branded professional women, especially artistic ones, as difficult domestic companions, who demanded a lot from their husbands, who were more unreasonable than any other woman, and that a man whose career or job differed from this type of woman would soon find himself in trouble. an unbearable situation.

In the same way and in accordance with what was expressed by the authors Carrión and Parrado (2019), although the female insertion into social life was shown in an unobjectionable way through its various spaces, among which the music academies had a notable significance, The presence of mentalities that rejected free female public expression and approved the teaching of music as ornamental lessons that highlighted feminine beauty and delicacy, but minimized their formative potential and the knowledge they transmitted, was also brought to the fore, an aspect that coincides with what is described by Valdés Cantero (2005). It is also correct if it is confirmed with what Botella (2018) said, that the interpretation of the results achieved from the multiple perspectives that academics have currently made visible on the subject, moved the authors' reflection. to several considerations.

Socio-historical, cultural and gender factors conditioned female musical practices, making it possible for teaching to become a notable field of performance for women during the first half of the 20th century (Conde, A. and Herrera, G. (2017 ), coinciding in criteria for Pinar del Río, in which their contributions to teaching and musical culture in general were minimized, as a result of the androcentric models of interpretation and understanding prevailing in the period studied, which incorporates the consequences of the economic, political and social subordination of the region to Havana, as the country's capital.

The Music Academies in Pinar del Río had the leading role of women, who with their sacrificial work made it possible for these institutions to fulfill the objectives of being true cultural agents, and to become channels of expression of the Cuban pedagogical-musical thought of its time, as expressed by the researcher Díaz Canales, T. (2018).

For education professionals, the result constitutes a developmental conception of learning, in order to promote innovative content that encourages new knowledge in the teaching-learning process that is developed in the Cuban educational system.

The importance of incorporating the gender perspective into historical and pedagogical studies was confirmed, as it allows us to recognize that female experiences make up a specific history, although it is not separated from that of men.

The participation of Pinar del Río women in musical education, during the first half of the 20th century, is part of the Pinar del Río culture and identity and forms the intangible cultural heritage of the province that must be studied and protected for future generations.

Referencias bibliográficas

Alvarado, R.A. & Trejo, R. (2022). Entender la educación musical como un derecho humano. Revista Internacional de Educación Musical. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364613147_Entender_la_educacion_musical_como_un_derecho_humano [ Links ]

Barceló, N.T. & Rodríguez, D. (2009). Pensamiento musical-pedagógico en Cuba: historia, tradición y vanguardia. Editorial Adagio [ Links ]

Botella Nicolás, A. M. (coord.) (2018). Música, mujeres y educación. Composición, investigación y docencia. Revista Electrónica Complutense de Investigación en Educación Musical, 17, 161-162. https://www.plateamagazine.com/libros/6333-ana-maria-botella-coord-musica-mujeres-y-educacion [ Links ]

Carrión, L. & Parrado, O.L. (2019). La participación de la mujer cubana, una necesidad para el desarrollo de la sociedad, Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales. https://www.eumed.net/rev/caribe/2019/01/ [ Links ]

Conde, A. y Herrera, G. (2017). Pensamiento pedagógico cubano 1902- 1920. Crítica y conciencia en la República. Nuevo Milenio. ISBN 9590620582. https://bit.ly/49e3uXI [ Links ]

Díaz Canales, T. (2018). Mujer- Saber- Feminismo. RUTH. ISBN:9789590623097, https://bit.ly/45Ph6FC [ Links ]

Rosales Vázquez, S., Esquenazi Borrego, A., & Galeano Zaldívar, L. (2017). La brecha de educación en Cuba con un enfoque de género. Economía y Desarrollo, 158(1), 140-151. https://revistas.uh.cu/econdesarrollo/article/view/2119 [ Links ]

García-Gil, D., & Pérez-Colodrero, C. (2014). Mujer y Educación Musical (escuela, conservatorio y universidad): dos historias de vida en la encrucijada del siglo XX español. DEDiCA Revista De Educação E Humanidades (dreh), (6), 171-186. https://doi.org/10.30827/dreh.v0i6.6971 [ Links ]

González Suárez, M. (2002). Feminismo, academia y cambio social. Revista Educación, 26(2), 169-183. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/440/44026217.pdf [ Links ]

Hernández, N. (2017). La educación musical de las mujeres en el conservatorio de Madrid en el siglo XIX y su proyección laboral y social. Universidad de Alcalá: España. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=179012 [ Links ]

León de la Paz, Y., Beltrán Marín, A. L. y Guillot Pérez, H. (2019). Panorama histórico de la educación musical en Cuba y Sancti Spíritus. Pedagogía y Sociedad, 22(55), 29-51. http://revistas.uniss.edu.cu/index.php/pedagogia-y-sociedad/article/view/735 [ Links ]

Lugo, J. G. (2020). El proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de la cultura musical cubana en los estudiantes de onceno grado. Revista Conrado, 16(72), 269-277. https://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado/article/view/1243 [ Links ]

Morales, P., Molina, M., & Vázquez, M. (2017). Una mirada de género a los estudios históricos en Cuba. Revista Conrado , 13(58), 195-200. http://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado [ Links ]

Torrent Esclapés, R. (2012). El silencio como forma de violencia: Historia del arte y mujeres. Arte y Políticas de Identidad, 6, 199-213. https://revistas.um.es/reapi/article/view/163001 [ Links ]

Valdés Cantero, A. (2005). Con música textos y presencia de mujer: diccionario de mujeres notables en la música cubana. Unión. https://bit.ly/3tHvTow [ Links ]

Soler Campo, S. (2020). Mujeres, música y liderazgo. Revista de estudios de género. La ventana, 6(51),111-137. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7862072 [ Links ]

Soler Campo, S. (2018). Cuestiones de género: mujeres en la historia de la música. Universidad Rovira Virgili. http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Artseduca.2018.19.5 [ Links ]

Received: October 27, 2023; Accepted: November 08, 2023

text in

text in