Introduction

The world has been constantly changing. The abrupt transition to e-environments has made organisational communication even more decisive than ever before. Deprived of the real-life interactions, managers have to develop communicative strategies for timely and targeted transmission of assignments, goals, and values to a large number of team-players in a business structure, an educational institution, a governmental body, etc. Under the conditions of physical distancing imposed by the pandemic, and, aggravated by the war in Ukraine, communicants experience difficulties in understanding messages to the full extent and recognising speakers’ emotions because of lacking extra-linguistic context. The importance of verbal expression has gained a greater prominence in learning behaviours and interpersonal communication among all academic actors. This compelling reality calls for redefining communication (Marra et al., 2020; Hesen et al., 2022), giving particular attention to language, its functions, and motivational potential.

Within linguistic domain, the study is aimed at verifying the possibility of mindful use of motivational vocabularies and verbal skillsets to stimulating higher performance in institutions. The specifically designed verbal strategies for communication in a university environment may significantly contribute to fostering motivation, inspiration, and the desire to grow and achieve higher results. This paper focuses on communicative aspects for motivating university community members. Based on the revised theories for their application to educational needs, it aims at revealing cognitive prerequisites of successful institutional communication through measuring reactions of pedagogic personnel and trainees to the motivational components in US educators’ speech. The results will be used for mindful use of language to ensure higher performance, building stronger corporate loyalty, co-values, self-identity, and confidence in future and career success.

The theoretical framework is structured in terms of general and specific issues of organisational communication discussed in the latest studies (Helens-Hart & Engstrom, 2020; Koyanagi et al., 2021; Dehling et al., 2022) blended with methodological approaches of cognitive linguistics (Lapaire, 2000; Lakoff & Johnson, 2003; Hampe, 2005) and empirical studies (Van Peer & Chesnokova, 2022).

The general scientific discourse on organisational communication is primarily evoked by the pandemic and other global circumstances, as, in time of crisis, scholars (Marra et al., 2020; Edvardsson & Tronvoll, 2021) seek to register changes in the field of organisational management. To meet the challenges of limited real-life communication, scholars recommend: 1) creating a favourable environment and a recursive organizational learning circle (Lenart-Gansiniec et al., 2021) for effective managerial action at individual, organizational, and institutional levels; 2) augmenting interrelated communications between university education participants by interprofessional education which promotes the idea of students’ collaborative competencies and behaviour (Teuwen et al., 2022); 3) maintaining effective communication and strengthening links between academic team-players at the level of particular disciplines and courses containing a well-thought interactive component (Hesen et al., 2022) by deciding which course elements are responsible for “community building, fostering subjectification and learning for being in an online course during physical distancing” (Hesen et al., 2022).

The bundle of specific issues refers to defining motivation as a central concept governing the intentional aspect of communication in academic setting and as moderator of effective communication at individual, group, and administrative unit levels. Whatever the approaches are offered to communication challenges in institutions, motivation is a constituent component of any activity. Any human initiative is driven by some intention, or motivation. It is “powering people to achieve high levels of performance and overcoming barriers in order to change”, - say Hamid Tohidi &Mohammad Mehdi Jabbari (2012).

Various other motivation scientists agree in that it is “the driver of guidance, control and persistence in human behavior” (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012); “motivation shapes own and peers’ educational success” (Bietenbeck, 2020), whereas motives are defined as what a person desires, needs, and strives for. On the one hand, scholars admit that the bulk of works on motivation has not converged on a common theoretical framework, system of measurement, or terminology (Murphy & Alexander, 2000). On the other hand, many of them agree that motivation is predictive of success in life which encourages related studies on the potential ways to boost motivation among students (Lazowski & Hulleman, 2016).

Motivation is a force which cause people to … have a behavior which brings the highest benefits for the organization; it is the force that causes movement in human (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). Both academic workers and trainees need something to keep them working, something more than a salary, or scholarship. They should be motivated. Otherwise, the performance both of instructors and students will be lower (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

The word “motivation” stems from Latin term “move” (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). At the same time, a thesis that image schemata pertain to sensory motor subconscious knowledge (Lapaire, 2000) evokes the interest in how schemata charged language units activate subconscious knowledge and serve as a stimulus, a driver, a motivating factor of human activity and what effect can be achieved due to the mindful use of schemata-charged language in communication between academic process actors.

Within linguistics, the study is aimed at testing the cognitive theory of image schema (Johnson, 1990; Lapaire, 2000; Lakoff & Johnson, 2003; Hampe, 2005) for establishing its feasibility in development motivational communicative strategies in academic setting.

In general, the theory implies people perceive the world through certain pre-conceptual entities structuring human experience in terms of spatial relations (Johnson, 1990). These are holistic structures, gestalts, belonging to primary knowledge, activating sensory motoric, neurophysical parameters of human sociophysical interaction with the world (Lapaire, 2000). When people interact, they perceive the message delivered, process ideas, form concepts, and respond. Their reactions and behaviors result from conceptualisation of the events, phenomena, situations, the information about which is processed in the framework schemata systems. Image schemata are abstractions, they are not fully refined images, they are generalized mental images and serve as bridges from perception to thinking.

The most discussed image schemata are Containment, Path, Source-Path-Goal, Blockage,

Center-Periphery, Cycle, Cyclic Climax, Compulsion, Counterforce, Diversion, Removal of Restraint, Enablement, Attraction, Link, Scale, Axis Balance, Point Balance, Twin-Pan Balance, Equilibrium (Johnson, 1990). These schemata are categorized in terms of three groups: spatial motion group, force group, and balance group. Other schemata by M. Johnson also embrace such abstractions as Contact, Surface, Full-Empty, Merging, Matching, Near-Far, Mass-Count, Iteration, Object Splitting, Part-Whole, Superimposition, Process, Collection (Johnson, 1990). Lakoff (1990), distinguishes two groups of schemata: Transformational group, including Linear path from moving object (one-dimensional trajector), Path to endpoint (endpoint focus), Path to object mass (path covering), Multiplex to mass, Reflexive, Rotation; and Spatial group, including Above, Across, Covering, Contact, Vertical Orientation, Length.

The schemata verbalised in communication may predetermine the ways messages are perceived by recipients. Armed with this knowledge, educators can enhance motivational power of their speech. This inspires to undertake the detailed analysis of the language data registered in educators’ speech and collect empirical evidence, which justifies the blended conceptual-and-empirical standpoint in pursuing the research objective.

The application of the image schema theory within the field of organisational management and cognitive linguistics is viable for elaborating new approaches to effective communication in education environment. The reason for this study lies in verifying the selected schemata charged content in educators’ motivational speech and the perceptions with the community of students and instructors. The research tasks imply the procedures aimed at verifying the hypotheses, as follows: H0 - there is no coincidence of the encoded schemata charged verbal units with the predicted respondents’ reactions in terms of the motivational potential; H1 - there is full or partial coincidence of these parameters. The practical value of this study lies in the contribution of its findings to the field of institutional communication, which stimulates further research aimed at seeking the optimal communicative strategies for better personal and professional performance in universities.

Materials and methods

This study embraced a network of cognitive, linguistic and stylistic, and empirical developments governed by the objective to reveal the cognitive parameters of motivational speech in a university learning environment. The study contained the elements both of qualitative and quantitative research methods. The qualitative aspect referred to the exploration of the experimental language material, which was the educators’ statements taken American University We Know Success website. This stage of the study included: 1) the procedures of content analysis and conceptual analysis for identifying the predominant conceptual structures shaping the motivational thinking; 2) annotating the verbal manifestations of image schemas based on the interpretative manual techniques; 3) the procedures of coding the revealed image schemas in terms of particularly designed variables, the example of which is illustrated in Table 6; and 4) collecting evidence of the prevalence of certain schemata in respondents’ thinking. In terms of the qualitative aspect, each opinion given by a respondent was valuable and was analysed as a representation of a particular set of image-schemas. By choosing an answer to a questionnaire item, the respondents shared their personal view on the academic process, leadership issues, instructor-and-student interaction, etc. The quantitative aspect of the study referred to the establishment of the tendencies in the respondents’ perceptions based on the descriptive statistics represented as percentage values, the results of which reveal the state of art in the institutional communication and communication needs of the BGKU university.

To this end, a range of methodological techniques was elaborated, which include:

the conceptual analysis method based on Johnson’s image-schema theory (Johnson, 1990) used to reveal the verbal manifestations of image-schemas according to the semantic criterion, i.e. the prevalent meanings predetermine the scope of a particular concept rendered by the schemata charged verbal means of expression;

the lingua-stylistic analysis of the verbal content of educators’ speech through the lens of its pragmatic potential “to motivate” communicants to reveal the correlation between the purpose of communication and the verbal means used;

the method of a survey to collect the opinions within the instructors and students’ community of the BGKU university;

the method of descriptive statistics, the results of which are expressed as percentage values.

The research was carried out in a stepwise manner:

The first stage - preparatory - implied: 1) the analysis of scientific literature data to establish the state-of-the-art developments at the crossroads of organisational management, positive psychology, pedagogics, and linguistics with reference to existing motivation-related challenges and various methodological solutions; 2) preliminary observations and analysis of the experimental language content, which implied the interpretation of the educators’ speech elements published at the website of the American University (https://www.american.edu/weknowsuccess/) and selection of the schemata charged statements for further linguistic and conceptual analysis.

The second stage - strategic - implied selecting language material for the study and designing the empirical research, with the focus on educators’ statements taken from American University We Know Success website (as far as BGKU instructors use English in their activities, the language units under the analysis are the verbal means of all structural levels of the English language as a system).

The third stage - conceptual analysis - implied conceptual analysis aimed at identifying image schemas manifesting in verbal means of the selected language material; revealing dominant schemata; and coding the verbal content of the research material with specific schemata. The fourth stage - linguistic and stylistic analysis - implied evaluating pragmatic potential of the educators’ and predicting respondents’ reactions.

The fifth stage - empirical study - implied the following procedures:

• developing the design (identifying recurrent schemata in the top US educators’ direct speech utterances; survey among pedagogical staff and students of the Institute of Philology at BGKU evaluating the research material in terms of motivational component; and revealing typical reactions); for statistical analysis we rely on the methodological school guided by Van Peer & Chesnokova (2022).

the sample size includes 36 graduate students and instructors of the Institute of Philology at BGKU, who took part in the survey by random choice. The limited number of participants did not affect the qualitative aspect of the analysis and data obtained. In this case study, the respondents showed their perceptions of the communication within the institution and personal attitudes. In terms of the quantitative aspect of the study, the quality was maintained due to the simple statistical methods revealing the overall tendencies in the participants’ responses, without establishing the causality between the variables. Moreover, a relatively small number of participants did not affect the quality of the linguistic study, because it represents the overall profile of the BGKU community. It should be noted that a distinctive feature of the university of is that its corporate culture embraces the principles of academic integrity, servant leadership, personal commitment to corporate values, and social responsibility. The sample was used as one pool of respondents, without division into control and experimental groups.

developing the questionnaire (the questionnaire was developed as a reflexive task and self-assessment activity in the end of the 2021-2022 academic year); the possible answers had been labelled with schemata in advance for identifying the cases of coincidence with schemata encoded language items;

organising psychological and pedagogical conditions of the survey (the ethic norms were observed, respondents’ privacy and confidentiality was ensured, EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules were fulfilled);

collecting survey data (the google form coded as MCASUS (abbreviated name of the paper) was offered); obtaining descriptive statistics data;

establishing the degree of image-schema recognition in respondents’ reactions, expressed in percentage;

interpreting the obtained results;

evaluating the feasibility of mindful use of the schemata charged language for enhancing motivational intentions in communication.

The outlined research roadmap enabled us to accurately observe the conditions of the study and reveal the motivational schemata-charged components of communication in academic environments.

Results and discussion

The literature review made at the preparatory stage and a range of procedures outlined above as strategic research planning, conceptual and linguistic stylistic analysis, creating of psychological and pedagogical conditions for collecting empirical data and a range of technical procedures outlined above have enabled us to organise the findings in terms of three parts: 1) recurrent schemata in educators’ direct speech utterances based on microcontexts (A); 2) findings of the survey among instructors and students of the Institute of Philology at BGKU (B); 3) revealing typical reactions and the cases of coincidence with encoded schemata (C).

For identifying the prevailing schemata in the educators’ speech, we have made the conceptual and linguistic analysis of 11 comments given by top educators and mentors of American University, Washington, DC: Jane Hall, Associate Professor, School of Communication (E1); David A. F. Haaga, PhD, Professor and Chair, Department of Psychology, College of Arts and Sciences (E2); Evan Berry, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy and Religion, College of Arts and Sciences (E3); Amy Eisman, Director of Media Entrepreneurship and Facilitator of JoLT (Journalism Leadership Transformation), School of Communication (E4); Nate Harshman, PhD, Associate Professor and Department Chair, Physics, College of Arts and Sciences (E5); Jody Gan, MPH, CHES, Instructor, School of Education, Teaching, and Health and the Public Health Program, College of Arts and Sciences (E6); Kiho Kim, PhD, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Environmental Science, College of Arts and Sciences, Director, AU Scholars Program (E7); Christine B. N. Chin, PhD, Professor, School of International Service (E8); Ken Conca, PhD, Professor of International Relations, School of International Service (E9); Tiffany Speaks, Senior Director, Center for Diversity and Inclusion, Office of Campus Life (E10); Bill Davies, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Justice, Law &Criminology, School of Public Affairs (E11).

According to the linguistic observations, the dominant schemata are UP, PATH, CONTAINMENT, LINK, ENABLEMENT (Tables 1; 2; 3; 4 and 5 below). Technically, we use the following symbols in the table: IS for image schema, […] for identifying image schema in the verbal content, and (E#) signifies the reference to particular educator as labelled above. The IS were identified by lexical-and-semantic criterion according to the meaning of the utterances derived from the context and by formal (morphological/grammatical forms) criterion.

Table 1 - UP image schema.

Table 1 illustrates the UP-schemata charged language units which are recurrent in the educators’ speech representing positive meanings in communication with current and former students. The UP-schemata charged lexical units actuate the meaning of “good” due to positive connotative meanings such as positive, best, successful, etc. The formal criterion implies markers that refer to comparative and superlative adjective forms more than, the best, transpositions in the category of number for nouns such as ups. The stylistic criterion refers graphical, grammatical, syntactical, and semasiological markers, e.g.: capitalisation (OK), antithesis (I’ve had my [ups] and downs).

Table 2 demonstrates the PATH-schemata charged language units which are recurrent in the educators’ s speech. The most prominent feature of this schematic projection is the formation of basic conceptual metaphor of JOURNEY. The conceptualisation of one’s success as a way to go through from the initial point to the endpoint is quite typical for education discourse and is verbalised with the help of such word combinations and clichés as career paths, pursue dreams.

Stylistically speaking, the cases of periphrasis, e.g.: a step ahead of where they are; metaphor, e.g.: to navigate the increasingly competitive and complex world; the trajectory of a student’s progress; guided by many questions and opportunities; enhanced with the case of alliteration e.g.: the twist and turns of the pathways, representing the possible challenges students may face on their way to success. In all these cases the target domain is goal as abstract notions and the source domain is path. This IS serves as a bridge between spatial perception and formation of the concept of journey, most commonly used for motivation purposes in the meaning of the long process and hard work resulting in success.

Table 2 PATH image schema.

Table 3 shows the CONTAINMENT schemata-charged verbal units directing communicants’ perception towards conceptualising abstract notions in terms of container, a closed entity filled with smth, e.g.: vessels to be filled, combined with IN image schema, i.e. something into which something can be put. There are also adjective with positive meanings, e.g.: it is delightful and stimulating, being inspired, most satisfying; abstract nouns denoting positive feelings, resources, possibilities, etc., e.g. energy, enthusiasm, verbalization of gratitude.

Stylistically, these are metaphorical projections such as source of pride, immersed in the field, actuated due to lexical units, whereas formal markers include prepositions with for filling with, providing with, in/within as in interested in, immersed in, prefix in- as in in-depth, etc.

Table 4 shows the verbal manifestation of LINK augmented with MATCHING image schema representations. The profiling of these schemata promotes the concepts of connection, cooperation, collaboration, linking, interaction, help, assistance, togetherness mostly traced in lexical means such as network, mutual relationship, help. The verbal traces of this image schema contain not only lexical and semantic means but also syntactical ones, when the meaning of linking derives from the syntactic structures containing the elements of communication in educational discourse, for instance, in the phrase said by (E6) and (E8). Stylistically, metaphors are formed in the meaning of connecting students and opportunities, so that the abstract concept of opportunity is personified. Formally, the concept of linking is supported by preposition with, between; prefix inter-, and adverbs together.

Table 3 CONTAINMENT image schema.

Table 4 - LINK image schema.

Table 5 profiles ENABLEMENT schemata charged language units verbalising the concept of ability, smth is able. It manifests explicitly in lexical units, e.g. opportunity, allowing, possibility, accessibility, empowerment, or implicitly through metaphors (E10), in phrases help ... achieve, in morphological components such as suffix -able. The concept of enablement is traced in activating their enthusiasm, actuating the LIGHT image schema in the meaning of turning on, enable. The LIGHT image schema is also partially traced in lexical units with positive meanings such as delightful and stimulating, unique insight.

Table 5 - ENABLEMENT image schema.

Some other IS combined with UP schemata identified are BALANCE, e.g.: [Teachers] are at their best when they [are also learners], … Being [treated as fellow] participants, I’ve had my [ups] and [downs], become more confident is [equally rewarding] (E7); providing for equilibrating the positions of instructors and students; ROTATION in the meaning of transformation, e.g.: skills to create positive social [change]. Other IS manifest in the language material with some weak implication, for instance build a strong combination can be understood in terms of ITERATION in the meaning of the stepwise development.

The empirical data were collected among students and instructors which study and teach in English. To reveal whether their perceptions and concept formation coincide with the encoded schemata the questionnaire was developed as a self-assessment and reflexive activity conducted at the end of 2021-2022 academic year. In general, 12 variables were tested. The questionnaire was available at https://forms.gle/RPdUcZ3EFC61GWxJ6 for BGKU community only.

The first two questions include general information such as status and attitude to communication for academic performance. Then, five statements specifically selected based on the results of the educators’ speech conceptual analysis (subsection A), as follows: “Do you find the phrase …?”:

S1: “what steps they might take to pursue their dreams”;

S2: “Each student has unique talents, so it is important to be flexible about their desired career paths”;

S3: “In my teaching and mentoring, I strive to help students make connections between their course work and the real-world problems”;

S4: “An important part of our mission as educators is to provide the kind of context that encourages and supports students' growth and success within and beyond classrooms”;

S5: “Students aren’t vessels to be filled; good teaching and mentoring are first and foremost about activating their enthusiasm”.

The variables, including predicted responses, had been encoded with the schemata identified in the course of the conceptual analysis, corresponding to statements 1-5 (labelled as S1, S2, S3 etc.) and other schemata selected randomly (the list is inexhaustive) for giving the respondents some choice in their interpreting the statements (table 6).

Table 6 - Predicting responses and schemata coding.

| UP/VERTICAL DIRECTION/ITERATION | Structuring experience | Not predicted |

|---|---|---|

| CENTER-PERIPHERY | Stimulating an individual approach | S2 |

| UP+VERTICAL DIRECTION | Promoting personality growth | S4 |

| LINK | Maintaining personal contact | S3 |

| PATH | Showing the way to personal development | S1, S2 |

| FORCE+IMPOSITION | Imposing an obligation to do something | Not predicted |

| ROTATION | Promoting personal transformation and change | Not predicted |

| IN-OUT | Calling for being outstanding | Not predicted |

| MOTION | Calling for being active | S5 |

| ENABLEMENT | Supporting, enabling | S5 |

| CONTAINMENT | Replenishing, enlightening and insightful | S4, S5 |

| COUNTERFORCE | Calling for counteracting | Not predicted |

| BLOCKAGE | Challenging | Not predicted |

Besides, the questionnaire contained two questions for evaluating feelings and emotions experienced in current communication, and three other questions for evaluating successful communicative strategies, motivational potential of the educators’ statements, and for choosing the advice to follow. The final parameter was an open question regarding respondents’ defining the concept of motivation.

36 respondents took part in the survey: 52.8% students and 47.2% instructors, tutors, lecturers, mentors, and administrative staff representatives (variable 1). Most of them responded affirmatively (91.7%) to the importance of communication and interaction for academic performance (variable 2). The responses to the educators’ statements as follows.

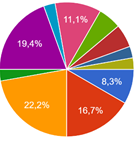

Variable 3 S1 (figure 1): what steps they might take to pursue their dreams” coincides with the encoded PATH schemata only partially (19.4) in the meaning of “showing the way to personal development”. Respondents mainly perceive this S1 in terms of UP and VERTICAL ORIENTATION schemata, which is rather strong in associations with motivation in communication (22.2%). They also evaluate the statement as “stimulating individual approach”, which refers to encoded CENTER-PERIPHERY as an alternative prediction. The respondents also mention ROTATION image schema, conceptualising the statement as “promoting personal transformation and change” (11.1%).

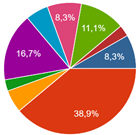

Variable 4 S2 (figure 2): “Each student has unique talents, so it is important to be flexible about their desired career paths” ... coincides with the encoded PATH schemata only by 16.7%, whereas the more prominent image schema according to respondents’ perception is CENTER-PERIPHERY (38.9%) which draws readers’ attention to student-centered approach in academic communication. This perception may be triggered by determiner each and lexical units unique rather than by career paths word combination. Stylistically, we can explain such result with that career path is a trite metaphor and cliché, which is automatized in perception, whereas the verbal means each, unique, talents, flexible give a novel vista on students’ development. Close to this meaning is the concept of being outstanding (11.1%), which extends the conceptualisation of CENTER-PERIPHERY schemata in the meaning of placing a student in the center of attention. The parameters promoting personal transformation and change and supporting are 8.3% either. The adjective personal enhances perceptions in terms of CENTER-PERIPHERY schemata.

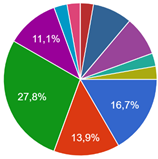

Variable 5 S3 (figure 3): “In my teaching and mentoring, I strive to help students make connections between their course work and the real-world problems” coincides with the encoded LINK image schema by 27.8% in the meaning of “maintaining personal contact”, which is the highest result in this parameter. Respondents also give 16.7% to “structuring experience” and 13.9% to “stimulating individual approach”, and 11.1% to “showing the way to personal development”. Other parameters are insignificant.

Variable 6 S4: “An important part of our mission as educators is to provide the kind of context that encourages and supports students’ growth and success within and beyond classrooms” has only 8.3% of coincidence with the encoded CONTAINMENT image schema. Instead, it is perceived rather as “structuring experience” possibly due to lexical units such as support, within and beyond and tends to be conceptualised in terms of UP and VERTICAL ORIENTATION schemata manifesting in positive connotative meanings. The statement is perceived as “promoting personality growth” by 19.4% respondents, “showing the way to personal development” by 11.1%, and either “stimulating individual approach” and “promoting personal transformation and change” are given 8.3%

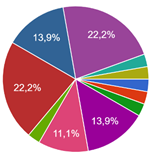

Variable 7 S5: “Students aren’t vessels to be filled; good teaching and mentoring are first and foremost about activating their enthusiasm” has 22.2% of coincidence with the encoded CONTAINMENT schemata, which proves the perception of the statement in terms of filling with, being full of. The equal result is given to “stimulating individual approach” parameter (22.2%), which speaks for the need in personalised communicative solutions. The perceptions of the statement either as “structuring experience” and “showing the way to personal development” are 13.9%, which shows some tendency towards conceptualising it in terms of UP and CENTER-PERIPHERY schemata. Also, 11.1% pertains to “calling for personal transformation and change”; “calling for being active” is only 2.8%, as well as other parameters (Fig 4 and 5).

For evaluating the feelings and emotions experienced in the current communication, the respondents gave their answers to “What feelings and emotions do you experience most often when you discuss your tasks and problems with your groupmates or peers?” (variable 8) and “What feelings do you experience most often when you discuss your tasks and problems with your teacher, instructor, tutor, supervisor?” (variable 9). The results for variable 8 are 25% - encouragement; 22.2% - the desire to grow and achieve best results; 13.9% - enthusiasm; and 11.1% - gratitude; variable 9 are 22.2% - inspiration; 19.4% - feeling that someone cares about me; 19.4% - the desire to grow and achieve best results; 13.9% - gratitude; and 8.3% - enthusiasm.

Three other variables are evaluating successful communicative strategies (variable 10), motivational potential of the statements (variable 11), and the advice to follow (variable 12). Variable 10: “Which of the qualities and strategies of communication in the university do you find the most effective for your achieving great results?” - 25% for “stimulating an individual approach” (CENTER-PERIPHERY); 13.9% - “showing the way to personal development” (PATH); 11.1% - “promoting personality growth” (UP); “maintaining personal contact” (LINK); “promoting personal transformation and change” (ROTATION). Variable 11: “Which of the above-mentioned statements and phrases told by educators awake an echo in your heart?” - 30.6% respondents pointed to S2 (David A. F. Haaga, PhD), (E2) (CENTER-PERIPHERY and PATH); 27.8% - S4 (Christine B. N. Chin, PhD) (E8), (UP and VERTICAL ORIENTATION); 22.2% - S3 (Evan Berry, PhD), (E3), (LINK); 11.1% - S5 (Evan Berry, PhD), (E9) (CONTAINMENT and CENTER-PERIPHERY); 8.3% - S1 (Jane Hall, Associate Professor), (E1), (VERTICAL ORIENTATION, UP, PATH). Variable 12: “Which of the above-mentioned advice and ideas would you like to follow?” - 30.6% respondents pointed to S2 (the statement by David A. F. Haaga, PhD), (E2) (CENTER-PERIPHERY and PATH); 22.2% - S4 (the statement by Christine B. N. Chin, PhD) (E8), (UP and VERTICAL ORIENTATION); 22.2% - S5 (the statement by Evan Berry, PhD), (E9) (CONTAINMENT and CENTER-PERIPHERY); 19.4% - S3 (the statement by Evan Berry, PhD), (E3), (LINK); and 5.6% - S1 (the statement by Jane Hall, Associate Professor), (E1), (UP, PATH).

The purpose of the study was to reveal cognitive and linguistic prerequisites of motivational communication within an education institution. The demand for such research has been predetermined by the need to maintain online learning at the sustainable level ensuring stable or increased performance of the university community under the conditions of physical distancing.

Such challenges are met in papers on management under hybrid working and learning conditions, which refer to tracing behavioral shifts and transformations in value co-creation, registering dependency between digital platforms and changes in actors’ mental models and institutional arrangements, paying attention to the role of motivation (…) (Edvardsson & Tronvoll, 2021); ensuring coordination of heterogeneous actors for value creation (Dehling et al., 2022). The referenced studies are focused mainly on the psychological factors of changing the behavioural patterns at institutions. In the context of the organisational communication paradigm, the conducted study complements the research of motivation problems with a linguistically substantiated approach and provides a new direction of the interdisciplinary field of work aimed at elaborating specific guidelines for enhancing the motivational component in communication within an institution based on a certain combination of image-schemas, pre-programmed in the verbal content. Therefore, this study highlights the ways of moderating personal and professional performance in institutions due to the linguistically grounded strategies of motivational communication.

Moreover, the psycho-pedagogical studies, such as those considering the problem of motivation the perspective of a hybrid educational design, supported by the mutual efforts of educators and students, reflective tasks and discussions enabling students “to see themselves as central subjects”, and encouraging their “personal exploration and sense of community” (Hesen et al., 2022) have been extended with the findings, which show that the use of the verbal means actuating ENABLEMENT, PATH, UP/VERTICAL ORIENTATION may strengthen the trainees’ motivation to be independent players. Giving students an opportunity to be on the same level as instructors enables their active learning position and activates enthusiasm. Therefore, this particular research is consistent with the general focus of the psycho-pedagogical studies and extends the scope of possible solutions aimed at assuring the student-centered approach in the course of learning and development.

In the context of the employee-oriented studies, this particular study supports the overall emphasis on employees’ well-being. However, such studies concentrate attention on personnel’s collection of soft skill such as active listening, perspective taking, audience adaptation and communication style through empathy as a central construct in a professional portrait of a worker (Helens-Hart & Engstrom, 2020). Alternatively, this study reveals that instructors can maintain their emotional well-being and motivate others by using CONTAINMENT/IN schemata charged verbal means in their speech.

The motivation scientists also point to the need of reinvigorated studies and direct empirical attention to develop interventions to help students make connections between students’ learning activities and their lives (Albrecht & Karabenick, 2017).

A new field of prospective research is stimulated by exploiting the potential of cognitive linguistics. This study opens the possibility to develop the motivational communicative strategies through the mindful use of schemata charged language. For instance, the connections between learning-and-work activity can be enhanced by actuating LINK image schema in educators’ speech. Therefore, the methods of linguistics can be used for maintaining motivational intra-and-interrelated communication between instructors and students.

Conclusions

The results of our study confirm the alternative hypothesis in general. The following conclusions can be made. Firstly, the language material analysed from the conceptual perspectives shows recurrent verbal manifestations of UP, LINK, CONTAINMENT, PATH, ENABLEMENT schemata. The educators whose speech was taken as referential material of motivational communication use the verbal means representing the concepts of growth, development, connection, linking with, journey, a way to, filling with positive feelings and emotions, accessibility, opportunity, and possibility. Secondly, the respondents react to the experimental language content by conceptualising ideas through CENTER-PERIPHERY, UP, LINK, PATH, CONTAINMENT schemata. This finding discovers the increased necessity in personality/student-centered motivational communication which can be supported by the use of CENTER-PERIPHERY schemata charged verbal means. Thirdly, the respondents are not focused on the concepts shaped by ENABLEMENT schemata. Here we can assume that the needs in opportunities, possibility, and accessibility are met within the university community and facilities.

Methodologically, the study is a qualitative enquiry embracing conceptual, linguistic and stylistic analyses complemented with empirical findings. In view of interpretative nature of the conceptual analysis, we admit a tolerated error in identifying and commenting schemata. However, the coincidence of 4 of 5 conceptual parameters in the respondents’ reactions proves the feasibility of the study.

The personality-centered communication should be applied at the level of instructors for improvement their soft skills, whereas the student-centered communication should focus on trainees’ attitudes in the framework of the linguistic motivational strategies for their success in occupational activity. The results of the observations and processing of the empirical data show that the verbal means charged with CENTER-PERIPHERY image schema are the prerequisites for implementing the personality/student-centered approach in organisational communication.

The limitations refer to having a rather narrow sample (36 respondents), the access to whom is restricted by objective circumstances (lower engagement because of poor Internet connection on the occupied territories, probable emotional burn-out, etc.). This made us a unified pool of respondents, with no division into subgroups.

The prospects of further studies include extending the sample for registering the differences in the instructors and students’ perceptions by applying Independent Samples T-test (SPSS 26 for Windows) and developing linguistic toolkit for motivational communication in education institutions.