Introduction

English teachers find many difficulties to create meaningful learning contexts within the classroom, especially in economically and culturally underprivileged areas where many students are not motivated enough to learn English. Numerous teenagers do not feel confident enough to participate actively in the proposed activities and may even feel anxious. However, if English is taught in a distended and relaxed atmosphere, there is no doubt that a more effective language learning would take place. Anxiety can negatively affect students’ willingness to communicate in language classrooms and lists six major effects of anxiety on second language learning and performance: low academic levels in foreign language teaching, avoidance of interpersonal communication, speech and accuracy of learning can be cognitively affected, retrieval of information can be interrupted by ʿfreezing-upʾ moments students may face when feeling anxious, when the language learning experience is felt as a traumatic experience, it can influence the learner’s self-esteem or self-confidence negatively and the student’s own personality. It is believed that performers with high motivation, self-confidence and a good self-image generally do better in foreign language acquisition. Also, low anxiety appears to be conducive to foreign language acquisition, whether measured as personal or classroom anxiety. The curriculum proposes notional, functional and situational topics that do not motivate teenage students and have been taught for decades. Little attention is paid to the real emotional and psychological characteristics of teenagers that look for rewards and quick feedback. With the goal of providing students with a distended atmosphere where they can feel more relaxed and motivated, a gamified didactic unit has been implemented in order to try to improve the oral communicative competence of a group of twenty-two fourth compulsory secondary education students of a high school in Madrid.

Being aware of the impact of affective factors on the language learning process, extensive research literature on the subject has proved that the way a language is taught is crucial and essential for its development. It is necessary to apply high standard student-centered programs, suitable instruction for students’ level and linguistic and academic integrated stimulating instruction. Thus, following the previous precepts, if students are offered new opportunities to learn the English language, they experience it in a ludic and entertaining way, the objectives are clearly settled and participation is fostered, students could certainly be very motivated, engage successfully in their learning practice and improve their English command. To do so, a different syllabus is necessary. Focusing on students’ needs, this work also proposes an engaging learner-oriented unit in which the different linguistic skills are developed while learning new grammatical and lexical structures. Moreover, oral skills will be more reinforced since these skills traditionally are less practiced in the classroom and the aim of the work is to help students improve their oral linguistic competence. Thus, students’ needs could be fulfilled and participation and cooperation would be constantly enhanced, following the cooperative learning principles and fostering interaction and communication in all the lessons. In addition, the use of authentic materials provides teachers and students with an assortment of materials that were unthinkable just a few years ago, which can be easily exploited within the classroom, and can increase students’ motivation, and consequently, participation, engagement and learning. Textbooks can be considered a good instrument, but generally they do not pay much attention to pronunciation which is the base of oral skills and accord an overwhelming importance to written skills.

Bearing in mind the current times, that is, a reality that evolves quickly where political frontiers are open and the flow of world citizens is more noticeable each day, people who are not able to communicate in a foreign language coherently, fluently and cohesively, limit their personal and professional opportunities. In this respect, teachers should be aware of the 21st century demands, and should enhance communicative tasks and atmospheres within the classroom. Thus, this work is focused on the use of gamification to try to improve students’ oral communicative competence.

Gamification can be defined as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts” (Deterding, et al., 2011, p. 10). It is a very attractive active methodology that has been proved to increase students’ motivation (Armstrong, & Landers, 2018), improves learning transfer and increases knowledge retention (Cordero, & Núñez, 2018) and thus, eases the development of students’ competences. They both develop their learning autonomy and cooperative grouping strategies (Marín, 2018). It operates due to certain underlying theories: Pink’s intrinsic motivation theory (2010), which is based on Ryan & Deci’s self-determination theory (SDT) (2000), goal setting theory (Latham & Locke, 1991) and Csíkszentmihályi’s Flow Theory (1990). Students can be more motivated when feeling satisfied with the activities they need to fulfil. Pink’s intrinsic motivation theory (2010) is based on Ryan & Deci’s self-determination theory (SDT) (2000) which explains the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. When gamifying, teachers need to promote intrinsic motivation in order to make students feel their autonomy and competence while enjoying participating and learning with all the proposed activities. Intrinsic motivation is related to three drivers: mastery, autonomy and relatedness which are defined by Pink (2010) as mastery, autonomy and purpose, which comprises four essential elements of intrinsic motivation: relatedness, autonomy, mastery and purpose. Relatedness represents the wish of having relationships with others and is one of the key elements in gamification. Being loyal in a community, for instance, demands having natural and good relationships with its members. Within this driver, the reward status can be found. Autonomy is related to freedom and the capacity of choosing by yourself. It provides learners the feeling of control of the actions that need to be fulfilled in order to achieve their goals. In addition, mastery is the process through which a skill is acquired in order to develop a certain activity. Difficulty needs to be balanced not to overwhelm or bore the learner. This concept is described by Csikszentmihalyi (1990) as flow, that state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else matters. This mastery or flow is necessary for gamification to keep players motivated through bearable challenges. Finally, the purpose is the need to find meaningful actions. Students working in cooperative and collaborative groups provide the best they can offer in order to benefit the whole group and fulfill the established goals. Latham & Locke (1991), who proposed the goal-setting theory, defend that students’ motivation can be promoted when the goals of the gamified experience are specific and moderately challenging. Goals are related to their performance, and therefore, to their content and intensity. Regarding the content, attention should be paid to specificity and difficulty. Concerning intensity, its major aspect is commitment, which can be defined as “the degree to which the individual is attached to the goal (Latham & Locke, 1991) which can work as a direct causal factor or a moderator of performance. High commitments lead to better performance and vice versa. Csíkszentmihályi’s Flow Theory (1990) shows engagement depends on the degree of concentration. The flow is a state which takes place when a person is completely concentrated in an activity which is challenging but balances personal skills, previous knowledge and the acquisition of new contents. The intensity of an experience increases with the distance from the actor’s average levels of challenge as it can be seen in the following (figure 1). The vertical axis represents the amount of difficulty of the task and the horizontal axis refers to students’ perception of the level of the skills. The combination of both axes produces the depicted states: anxiety, worry, apathy, boredom, relaxation, control, flow or arousal.

This theory demonstrates humans like being in a flow state that triggers intrinsic motivation, which is so beneficial in educational contexts. As Sun & Hsieh (2018) argue, gamification is an effective method to increase students’ motivation and engagement and improve their attention and attitude. Thus, it also helps students improve their different linguistic skills, as it occurs in Lam, et al. (2018), in which a gamified is used om order to improve argumentative writings, Mogrovejo, et al. (2019), who proved how gamification can help students widen their English lexicon or Barcomb, & Cardoso (2020) study revealed the use of a gamified system improved the participants’ pronunciation. Purgina, et al. (2019) research worked on the efficacy of a gamified mobile application when learning EFL and Hernández-Prados, et al.’s work (2021) analyzes the perception of the gamified use of board games in the EFL secondary education classroom. They are positively valued and their use seems to be beneficial towards the students’ EFL learning.

Though providing a few examples of research on gamification conducted with secondary education students, their findings show the implementation of gamification is always successful when teaching EFL. It has been observed that with gamification, there have been improvements in the acquisition of lexicon, pronunciation, argumentative writings and students’ motivation, something crucial when working with teenagers.

Materials and methodology

Bearing in mind that it is challenging to make teenagers feel motivated during their learning process, the aim of this work is to know secondary education students’ perception about the use of gamification in the EFL classroom. The present research starts from the hypothesis that gamification of learning could be a suitable and motivating methodology for teaching EFL in Spanish secondary education, with a positive influence for its students to improve their linguistic competence. It has been proved to be efficient in the EFL secondary educational classroom in other educational contexts such as in Switzerland (Baur, et al., 2015), Taiwan (Sun & Hsieh, 2018), China (Lam, et al., 2018), Japan (Barcomb & Cardoso, 2019) or Peru (Mogrovejo, et al., 2019), and thus, similar results are also expected in Spain. The research question of this study aims to analyze the learners’ attitude towards the methodology experimented. In order to meet the objectives of this study, a quantitative approach has been chosen, through a non-experimental and descriptive research since no variable has been manipulated but rather observed as they are presented and analyzed by means of descriptive statistics.

Participants

The sample population of this study is made up by twenty-two fourth-year compulsory secondary education students (n= 22) of a semi-private school with three sections per grade in Madrid downtown (Spain). Participants’ age ranges from 14 to 15 when the experimentation started (M: 14,77; SD: 0,42) with a larger percentage of female students 81.81% versus 18.19% of male students. All the students are Spanish with Spanish as their mother tongue language. The selection of the sample was intentional through non-probabilistic sampling by accessibility. The inclusion criteria for the sample were to be enrolled in the fourth year of compulsory secondary education at the school, to attend class regularly, to have signed parental/legal guardian consent and not to have a diagnosis of specific learning difficulties, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or other neurodevelopmental disorder, or sensory and/or psychological problems.

Instrument

As instrument for data collection, in order to identify the participants’ perceptions once the experimentation was finished, an experience questionnaire based on (Lizzio, et al., 2002, 50-52) was administered. The questionnaire was divided into two sets. The first set was composed of twenty-three Likert-scale close-ended items (strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree and strongly agree), through which students were asked about six fields: the gamification teaching practice, goals, assessment, workload, independence of learning and development of skills (see Table 1). The scores range from 1 to 6 points respectively and will clarify the participants’ attitude towards the use of gamification in the EFL classroom.

Table 1 - Sections, items of the six sections and coding

| Section | Item | Coding |

|---|---|---|

|

Teaching practice |

Emphatic responsiveness | Q1.1. |

| Motivating expectations | Q1.2. | |

| Understandable explanations | Q1.3. | |

| Stimulating learning designs | Q1.4. | |

| Helpful feedback | Q1.5. | |

|

Clear goals |

Clear aims and objectives | Q2.1. |

| Direction: provides progressive markers of “where we are going” | Q2.2. | |

| Expected standards of work explained | Q2.3. | |

|

Appropriate assessment |

Type: emphasizes understanding | Q3.1. |

| Progressive and spaced timing | Q3.2. | |

| Developmental feedback | Q3.3. | |

|

Appropriate workload |

Feasible volume of work | Q4.1. |

| Breadth of curriculum | Q4.2. | |

| Adequate time availability | Q4.3. | |

|

Independence of learning |

Curriculum content: developing areas of academic interest | Q5.1. |

| Learning process | Q5.2. | |

| Assessment modes | Q5.3. | |

|

Generic skills |

Use of analytical skills | Q6.1. |

| Development of problem-solving capabilities | Q6.2. | |

| Development of written communication skills | Q6.3. | |

| Application: using problem-skills to tackle unfamiliar problems | Q6.4. | |

| Collaboration: working as a team member | Q6.5. | |

| Self-regulation: planning their own work | Q6.6. |

Source: Own elaboration

Besides, in the second set, participants also answered three open-ended questions in which they spoke about what they like best about the course and what they liked worst. They could also include what they would add to improve the gamification experience.

Procedure

Hard copies of the questionnaire were administered once the experimentation was finished. All the data were collected in compliance with the ethical guidelines of Helsinki Declaration and the confidentiality of the data was guaranteed. All the contents worked in this experimentation always respected the curriculum established by the State and the Madrid community, the Royal Decree 1105/ 2014 of December 26th, 2014 (Spanish Ministry of Education: 430-435) through which the minimal teachings are established which is further developed by the Madrid Community in the Royal Decree 48/2015 of May 14th (BOCM May 20th).

This educational experience took place during the school year 2020-2021, from October 2020 to June 2021. The teaching took place in the students’ usual classrooms with optimal lighting, ventilation and sound conditions.

Results

The Social Science Statistical Package SPSS (Windows version 25) was used to carry out the analyses. Descriptive correctional statistics were used to find out the means and standard deviation of the studied variables. The bulk of the sample shows a positive attitude towards the use of gamification (see Table 1). The results of the twenty-three statements will be discussed in detail below and shown in Table 2. The means of the different sections are as follows: for the first dimension, the teaching practice, 5,22. For the second section, clear goals, 5,02. The third section, appropriate assessment, 5.04. The fourth one, appropriate workload: 4,66. The fifth one, independence of learning, 5,13 and the last one, generic skills, 5,22. All the sections have been positively valued, since all the items range from slightly agree to strongly agree with a means between moderately and strongly agree. The most positively valued dimensions have been the teaching practice and generic skills with a mean of 5,22. If a deep analysis of the different sections is done, it can be observed that regarding the first section, the teaching practice, the highest score is given to Q1.4 (stimulating learning designs) with an average value of 5,45 and Q1.2. (motivating expectations), with 5,31 points. The lowest scores correspond to Q1.3 (understandable explanations) with a score of 5.04 and Q1.1. (emphatic responsiveness) with 5,09 points. Regarding the second section, which covers the goals of the subject, answers are similar in the three items. In Q2.2. (direction) and Q2.3. (standards of work), the mean is 5,04. In Q2.1. (clear aims and objectives) the average score is a bit lower (5,00) which defines most of students moderately agree on that statement. As far as the third section is concerned, which analyzes assessment, students provide a score of 5,18 for items Q3.1. (type, emphasizes understanding) and Q3.3. (developmental feedback). However, Q3.2. (progressive and spaced timing), has been given one of the lowest scores, 4,77 points. It seems students need more time for all the proposed tasks to be properly assessed. It has also been the item with a higher deviation (SD= 1,19), which implies that there is little agreement on its answers. This score is in line with the ones obtained in the fourth section, appropriate workload. In item Q4.1. (volume of work), the average score is 4,59, in Q4.2. (breadth of curriculum), 4,90 and in Q4.3. (time availability), 4,50, which is the lowest score in the whole questionnaire. Students feel they were not allowed adequate time frames for work to be completed. The standard deviation of the lowest scores is, to a certain extent, also high: for Q4.1., the deviation is 1,18 and for Q4.3., 1,14. Despite being the lowest scores, it seems there is not a large agreement on these items.

As regards to section five, independence of learning, results are more positive and all of them are above five points (moderately agree). Q5.1. (curriculum content) has an average score of 5,04, Q5.2. (learning processes), 5,22 and Q5.3. (assessment modes), 5,13. Finally, the last section (generic skills) provides the most positive results. Item Q6.5. (collaboration, working as a team member) offers a mean score of 5,54, followed by items Q6.4. (application, using problem-solving skills to tackle unfamiliar problems) and Q6.6. (self-regulation), with 5,22 points. Q6.6. is the item with the lowest standard deviation (,61) followed by Q6.5. (,67), which shows there is a great homogeneity among the participants’ answers. The lowest scores, though above five points, are the ones provided in Q6.1. (use of analytical skills), with 5,04 points, Q6.2. (development of problem-solving capabilities), with 5,13 points and Q6.3. (development of written communication skills), with 5,18 points.

All these figures show the participants of the study show a very positive attitude towards the use of gamification since all the items of the questionnaire have been very highly valued and there is not any item they have disagreed with.

Table 2 - Descriptive Statistics

| N | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | |

| Q1.1. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,09 | 0,97 |

| Q1.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,31 | 0,83 |

| Q1.3. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,04 | 0,78 |

| Q1.4. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,45 | 0,85 |

| Q1.5. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,22 | 0,86 |

| Q2.1. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,00 | 0,92 |

| Q2.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,04 | 0,95 |

| Q2.3. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,04 | 0,72 |

| Q3.1. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,18 | 0,79 |

| Q3.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 4,77 | 1,19 |

| Q3.3. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,18 | 0,79 |

| Q4.1. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 4,59 | 1,18 |

| Q4.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 4,90 | 0,86 |

| Q4.3. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 4,50 | 1,14 |

| Q5.1. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,04 | 0,95 |

| Q5.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,22 | 1,06 |

| Q5.3. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,13 | 1,03 |

| Q6.1. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,04 | 0,84 |

| Q6.2. | 22 | 3,00 | 6,00 | 5,13 | 0,83 |

| Q6.3. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,18 | 0,85 |

| Q6.4. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,22 | 0,75 |

| Q6.5. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,54 | 0,67 |

| Q6.6. | 22 | 4,00 | 6,00 | 5,22 | 0,61 |

Source: Own elaboration

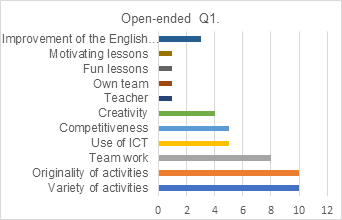

Regarding the second set, which comprises three open-ended questions, students highly valued the gamified experience and working in cooperative groups. As it can be seen in Figure 2, what informants valued the most was the variety and originality of the activities. In second position, they highlighted team work and in a third place, the use of ICT tools and competitiveness. Creativity was considered the fourth most valued element and the improvement of their English skills, their teacher, own team, and fun and motivating lessons were relevant elements they wanted to mention too.

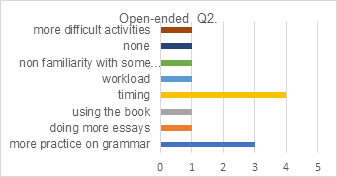

On the other hand, among the elements that needed improvement, Figure 3 shows timing (as it was reflected in the first set too) and more practice on grammar. This information, together with other elements also included in this section (i.e. the use of the course book or doing more essays) lies in the fact that students were used to the traditional communicative method and in previous years, they usually followed course books and teachers usually emphasized the use of a correct grammar. Moreover, they were only assessed on their grammar and written skills with written tests. It was not unusual to find this type of comment since it was what they had always been expected from them. Comments on workload were also present, which are in accordance with the timing issue.

Finally, in the last question, students could make any comment they considered necessary. As illustrated in Figure 4, 59,09% of participants answered this question and all the comments were positive. All the comments insisted on the “fun” element of the lessons and on the fact that they were aware of their learning while enjoying the lessons.

Discussion

The purpose of this research is to analyze to what extent gamification could be a suitable methodology for teaching EFL to the sample of study, and therefore, it may also be effective when working with other populations with similar variables. The study aimed to analyze the learners’ attitude towards the methodology experimented. The results of this study indicate that participants hold a very positive view of gamification in their EFL context. Students positively value working in collaborative and cooperative groups, feel they are listened and respected, believe they improve their linguistic and generic skills and are aware of their learning process. As items Q3.2. and Q4.3. reflect, timing needs to be adjusted in order to allow suitable time frames to complete the workload. In the line with the research conducted by Sun & Hsieh (2018) students felt very motivated, interested and engaged in the lessons. Their skills, both linguistic and generic skills, improved due to the gamified experience, as it also occurs in Lam, et al.’s (2018) and Mogrovejo, et al.’s (2019) works.

As evident in Hernández-Prados, et al.’s work (2021), the use of analogical tools is positively valued. In this research, they have been combined with digital resources so students have always been expectant and active in their learning process.

Conclusions

In the light of the results obtained in this exploratory research and the scare studies focused on gamification and EFL at the secondary education stage, it would be convenient for EFL secondary education teachers to choose the use of gamification in their classes in order to increase students’ motivation, engagement and consequently, linguistic competence and generic skills.

This research has had some limitations that are identified and may modulate the interpretation of the results. On the one hand, regarding the research methodology, the assignment of students was done by convenience and not randomly. To mitigate this, a preliminary analysis was performed to verify that there were no differences in sociodemographic variables such as gender or age that could influence the results obtained in the research. On the other hand, regarding the design study, it is a pre-experimental study of a single group. This choice was considered so that all students could have the same teacher and all received the innovative proposal in the real context of the classroom. Finally, the work focuses on secondary education students enrolled in an EFL course who learn English in gamified educational environment. Despite scientific literature that different designs should be adopted depending on the learning task, in this work the same procedure and methodology (gamification) and different resources (but all of them gamified) have been used in the classes, so it is estimated that the effect observed in the students’ perception was due to the innovative proposal itself.

Future research could be aimed at increasing the sample size and applying it in other disciplines, educational stages and international contexts, thereby, testing the proposal on other types of students. Future work could extend the analysis to other variables that provide objective data, such as academic performance, a validated test on motivation, etc. Moreover, the use of other types of qualitative and/or quantitative methodologies (depending on the variables used and their operationalization) could be introduced to enrich the results obtained.

The pedagogical implications are aimed at the teaching-learning process in secondary education. First, the empirical evidence that students enjoy this way of learning much more than through traditional communicative language teaching methodology. Secondly, the implemented proposal had a duration of a whole school year (ten months) which is considered to be a substantial period of time for the results to be reliable. Thirdly, research could be extended to university contexts or to other subjects and courses. The constant interaction among the teammates, the development of interpersonal skills and of their autonomy and the high engagement and motivation of students, which helps to increase knowledge, facilitate the acquisition, not only of the target language in a distended atmosphere, but also of the different competences that need to be fulfilled by the end of secondary education. The fact that students show a positive attitude in gamified lessons make them increase their active participation and their self-confidence. As a result of the interaction among students, they also improve their oral skills.